Reforming the Supreme Court

A novel proposal for making SCOTUS appointments more responsive to election outcomes.

In searching this morning’s post on the trend toward younger appointees to Federal judgeships, I came across an interesting essay by legal scholars E. Donald Elliott and John Attanasio from last October titled “Fixing a broken process for nominating US Supreme Court justices.”

Their statement of the problem is familiar:

President Donald Trump has nominated two Supreme Court justices during only 19 months in office.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell stated after Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation that Trump might have the opportunity to make a third nomination during one term in office. By the end of a possible second Trump term, he could choose a majority of the Supreme Court.

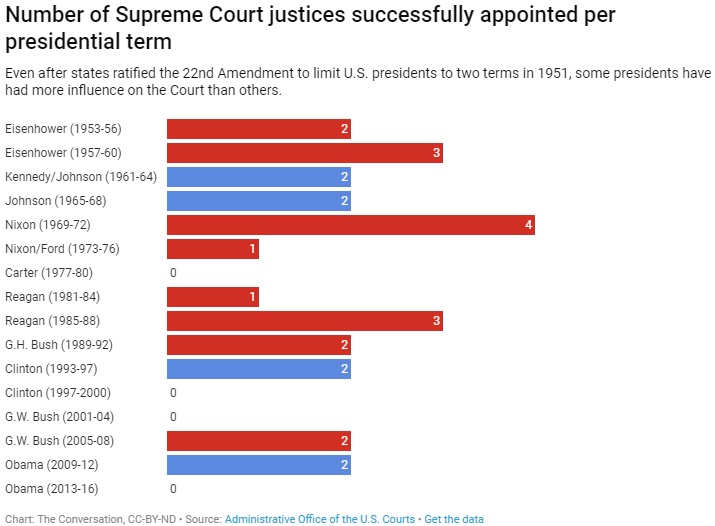

While the Supreme Court is not a representative body, justices on that court have strong, well-developed and significantly different judicial philosophies and approaches to constitutional and statutory interpretation. Presidents openly admit that they make their nominations significantly based on these factors. Under the present system for nominating Supreme Court justices, voters in some elections have two or three times more influence over Supreme Court appointments than those in others.

This is anomalous and unfair because voters in one election usually have the same opportunity to elect government officers as those in another. But because a congressional statute fixes the size of the court at nine, some presidents will have the opportunity to nominate more Supreme Court justices than others, based on the happenstance of deaths or resignations.

They provide quite a bit of detail in written form but this graphic illustrates their point quite vividly:

Most reforms suggested to remedy such problems, such as limiting Justices to a 12-year term, would require a Constitutional amendment—which would be nearly impossible. Others, like simply increasing the size of the Supreme Court to allow the next Democratic President to rebalance it ideologically (and make up for cynically keeping Merrick Garland from his seat) would set off a game of tit-for-tat. Elliot and Attanasio have a simpler, more elegant solution:

We think this is backwards: Each president should get an equal number of appointments per elected term and the size of the court should fluctuate over time as vacancies occur.

Fixing this phenomenon does not require a constitutional amendment. We are legal scholars who have written across a broad swath of areas including constitutional law. We believe Congress could pass a law providing that a president gets two Supreme Court appointments per four-year term in office.

The Constitution does not dictate the size of the Supreme Court; Congress does.

This new system would mean that the number of nominations a president gets would no longer fluctuate depending upon the vagaries of deaths and vacancies on the bench.

[…]

Under our proposal, Congress could pass a law that stipulates a president would get two nominees, and only two nominees, to the Supreme Court per four-year term. If that nominee were rejected by the Senate, the president would get to keep nominating until one was successfully confirmed. A death or resignation from the court would not entitle a president to name additional justices.

They defend against one obvious challenge to their idea:

Under our proposal, the Senate would have a legally binding obligation to confirm two nominees each presidential term.

Of course, the Senate could still thumb their noses at any presidential nominee, as it did with Garland.

We doubt that this would happen. First, under our proposal, the president does not have to wait for a death or retirement of a justice to nominate. Instead, the president controls the time frame. If presidents make the nominations within several months of their election, we doubt that many Senates would have the temerity to vote down nominees for four years. The argument for delaying confirmation that has emerged since the unsuccessful Garland nomination has been the Senate controlled by the opposition party does not confirm nominees to the Supreme Court within a year of an upcoming presidential election. As presidents would have the right to make nominations as soon as they assumed office, the Merrick Garland problem will likely never happen again.

But suppose the Senate simply refused to consider a president’s nominee either within one year of the presidential election or even before that – what then?

We suggest that Congress pass a statute requiring the Senate Judiciary Committee to hold hearings on any presidential nominee within two months. They would also be required to bring the issue to the floor for a roll call vote within a reasonable time, say four to six months of the nomination.

Failure to meet these deadlines would result in automatic confirmation. Any senator could enforce these requirements.

Some might think that this approach infringes on the constitutional powers of the Senate to make its own rules. We think it would be constitutional, as it gives the Senate a fair opportunity to “advise and consent” as required by the Constitution.

Alternatively, if the Senate fails to meet these deadlines, the statute could imitate the procedures mandated by the budget reconciliation act and require the Senate to bring the nominee to the floor for a vote within a set period of time and prohibit filibuster, as the Senate has now done for judicial nominees.

They argue that their system would have produced a much evener distribution of appointments:

If such a statute had been in effect starting in 1952, the size of the Supreme Court would have fluctuated between seven and 14 justices. Each presidential election would have had equal weight in determining the composition of the court.

This system might reduce the incentive for justices to delay resigning so that certain presidents do not get a nominee, or for the Senate to stonewall a nominee until the next president takes office. Controversy surrounding some individual appointments could diminish.

Other scholars have criticized the current size of the court as too small because it leads to too many 5-4 decisions. These undermine the democratic legitimacy of the court, they argue, by suggesting that rather than applying law objectively, a single swing justice is deciding controversial issues for the country.

Many other notable courts are larger than ours. The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, created in 2005, has 12 members. The European Union’s highest court has 28 members.

This is not to say that we view the Supreme Court as a representative or legislative body. We believe judges should be constrained by texts. But within those constraints, justices do exercise judgment.

No good reason exists why some presidential elections should count for two or three times as much as others in determining how we are governed.

Two things they don’t account for.

First, their proposal would allow for an even number of Justices to be on the Court, potentially for years on end. Say the provision was already in place, meaning President Trump would already have exhausted his two appointments. (I’m sure we would grandfather this; I’m just using it as an easy example.) Then, one of the current Justices retires or dies in office. We’d be down to eight Justices for the remainder of Trump’s term, allowing the possibility of 4-4 votes that don’t resolve the issue at hand. And, until another Justice died or retired, we’d continue to have an even number of Justices: ten after either a re-elected Trump or his successor takes office in 2021, twelve in the next term, fourteen in the next, and so on.

Second, a legislative fix of this sort court theoretically be overturned whenever it was convenient for a subsequent legislature. Granting that a President would veto any bill stripping him/her of their two appointments, making it possible to do so only in the unusual instance of a supermajority of the opposite party in Congress, one could certainly see a supermajority of the President’s own party changing the rule in his favor. Then again, they could do that now.

Overall, though, this idea is a step in the right direction. It would almost certainly end the sad practice of Justices hanging out as long as they can hoping for a President of their political party to appoint their replacement. And it might well make a Merrick Garland scenario less likely. Indeed, it would be advantageous for a President to make her/his two appointments right at the beginning of the term to maximize their impact.

We’ve been at 9 SCOTUS seats since 1869 (from 1837 save for a three-year anomaly at 10), so it seems like holy writ. But a Court that fluctuated in the suggested manner actually makes more sense. Few believe anymore that Justices aren’t political actors, even partisan ones. We might as well make it reflect election returns in a more systematic manner.

One reason I am skeptical of this proposal is precisely because of the idea that it would inevitably lead to a Supreme Court of more than nine members, potentially substantially more than nine depending on the circumstances. While it’s true that nine Justices is not holy writ, the fact that it has been the norm for most of the time that SCOTUS has existed is a strong indication either of the alternatives — shrinking the size of the Court or increasing it — could be problematic.

Shrinking the membership of the Court, of course, would mean that there would be far fewer voices to consider the issues that come before the Court. In this regard its worth noting that, for the most part, the Supreme Courts on the state level have mimicked the custom we’ve had at the Federal level with a membership of nine justices, although there are some states that have fewer than that. (I am unaware of any State Supreme Court that has more than nine members.)

Increasing the size of the Court brings to mind practicality problems that would arise with respect to larger and larger bodies. How many SCOTUS Justices would be “enough?” 11? 13? 15? Obviously, it would have to be an odd number so as to avoid the problems that ensure in the case of an evenly divided court. At some point, though, I think the Court could get so large that it would have an impact on the effectiveness of body and the ability of the Court to do its job under Article III.

As an example of the problems a much larger Court would create, one need only look at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, the nation’s largest and busiest Court of Appeals. At present, there are 24 active Judges on the Court not counting those who have taken Senior Circuit Judge status. If you add in the 5 seats that are currently vacant, that makes for a membership of 29 Judges.

To a large degree, the 9th Circuit needs to be this big to deal with the sheer volume of appeals that come through its doors every year. One consequences of this, though, is that the court long ago ended the practice of having all of the active Judges participate when the Court sits en banc. Instead, if and when en banc review of a panel decision is granted it is assigned to an en banc panel consisting of 11 of the active Judges. This is not really what en banc review is supposed to be, and would be an impractical way for the Supreme Court to operate. This is one of the reasons why there have been many arguments made over the years to break up the 9th Circuit and create a new 12th Circuit Court of Appeals. So far, though, the various plans for how that would happen have been so far apart that Congress has not addressed the issue.

For that reason, I think sticking with the historical norm of 9 Justices is the best idea for now.

The other thing I’m skeptical of is the idea that the Court should be more responsive to electoral outcomes.

That’s not how the law is supposed to work and, indeed, I think the extent to which the Court has become a political issue is at the heart of why we are where we are.

@Doug Mataconis:

We’re in agreement. I just think the ship sailed a long time ago.

I wish I were exaggerating, but I believe that any “solution” that does not privilege Republicans is a nonstarter.

@Kit:

Realistically, that may well be right, at least in the near term.

@James Joyner: How about impeaching the appointed justices if it turns out that a Presidential election was illegitimate?

I think it’s all very well to examine the intent of the founders, but certainly the founders did not envision – could not, given Citizens United and the amount of dark money now influencing elections – a political party such as the GOP existing as it exists today, and changing the rules on the fly to continue to exist, up to and including packing the court so gerrymandering stands – in this day and age. If elections have consequences, what do stolen elections have?

Of course it is a nonstarter…they seem to have the idea that they are the exclusive provider of Supreme Court nominees…the Democrats should expand/pack the court as soon as they have the chance…

And 2016 when we were at 8.

@Doug Mataconis:

No. It is definitively not a good- or even acceptable plan – given the actual facts on the ground.

My plan:

1. Split the 9th. you right that 29 is too big. 15 or so isn’t. Most CoA are between 11 and 17 now (9th (29) and 1st (6) are the exceptions.

2. Create one SCOTUS Judge for each Circuit Court plus the CJ – a bench of 15.

@SKI:

There have been numerous instances where there was a vacancy. The 422-day vacancy was the longest in the modern era, surpassing the previous record of 389 days between Abe Fortas’ resignation and Harry Blackmun’s oath of office on June 9, 1970. But there have been vacancies as long as 841 days in the past, with seven longer than the one after Scalia’s death;

@James Joyner:

That wasn’t a regular vacancy or a situation where the Senate rejected a nominee. That was McConnell and the GOP refusing to consider *anyone* for a position. It was legislative action to hold the size of the Court down to 8. Considering it a “vacancy” is ridiculous.

@SKI:

Scalia’s death created a vacancy. Senate Republicans acted in bad faith to hold the seat open in hopes a Republican President could fill it. They succeeded.

The statutory size of the Supreme Court (the issue under discussion here) was 9. No intervening legislation was passed to allow Gorsuch to serve. The Senate simply confirmed him and filled the vacancy.

I would argue that the Supreme Court is presently slightly too large already. There is a body of empirical evidence suggesting that committees of more than seven members are unwieldy. Increasing the number beyond the present nine would make deliberations more difficult.

Also the notion that you can predict the decisions of particular justices based on the political party of the president who appointed him or her is, at best, an oversimplification. An examination of Supreme Court decisions over the period of the last generation or so tells us that relatively few cases are decided by 5-4 decisions and most of those are on “hot button” issues. We should be trying to make the courts less ideological not more ideological.

Perhaps the underlying problem is that too many cases involving “hot button” issues are going to the courts. In other words the problem isn’t the composition of the courts but the Congress and the state legislatures failures.

Your chart shows that since Jimmy Carter, who got no appointees, there have been eight appointments by Republican Presidents and four by Democrats. This certainly is not reflective of our national composition, and yet I sense that the GOP complains more about the court. Are they just working the refs? What are the upcoming big issues that the court will be deciding? Do Republicans really want to make it easier to sue newspapers for libel? How about free speech on campuses? Transgender rights? Transhuman rights?

@Slugger:

Yes, but the chart stops before Trump. So it’s actually 10 by Republicans and 4 by Democrats.

I think it’s because they’ve largely lost on the big social issues starting with abortion. Granted, they’ve won on gun rights, campaign financing, and some others but I think the former matter more to the base and therefore get used by pols as electoral fodder.

How about over the last 20 years…

@Dave Schuler: Contra point – we don’t have enough diversity on the Court to ensure that a full, fair understanding of an issue is achieved.

For a working committee with a shared purpose and goal, 7 or fewer may indeed be ideal to increase efficiency and speed.

For a governing board, where you are setting policy and agendas, you want more views, not fewer. The median size for non-profit boards is 13 and the average is 15. You don’t really want to get much bigger than that but you lose a lot of skill and perspective diversity with smaller boards.

@Slugger:

Not really. I think it is a perspective thing. When you are used to being dominant, equality feels like oppression. Starting with the Civil Rights movement and the Court’s support for equality, there has been a consistent anti-Court (and anti-elites) theme.

@SKI:

When you’re reaching a 15 person SCOTUS I think you’re reaching the point I referred to before, where the size of the Court becomes a hindrance rather than a help. The size of the Courts of Appeal may be a helpful guide, but remember that en banc hearings are rare. Most decisions are handed down by three-judge panels, which is not a procedure I would recommend for the nation’s highest court.

@Doug Mataconis: I agree that 3 seems much too few, but what about 7 or 9 drawn by lots, maybe with no more than one from each president (imagining the above solution of two per president had been implemented)?

@Doug Mataconis: Maybe 15 is too many but I think we can agree that there is a real shortage of diversity with the current size and the small size places an incredibly high weight on each and every vacancy – a weight and importance that distorts the proper functioning of the system.

Also, do our fellow representative democracies that have larger highest courts all have issues? Is there anything to be gleaned from their experiences?

@SKI:

A quick search reveals this from Anglo-Saxon countries that have some equivalent to a Supreme Court.

1. The United Kingdom has a Supreme Court made up of 12 members.

2. Canada’s Supreme Court has 9 members

3. Australia’s High Court, which appears to be their equivalent to SCOTUS, has 7 members

4. New Zealand’s Supreme Court has 5 members

5, Ireland’s Supreme Court has 8 members

I didn’t look at any other countries because other nations (especially those whose legal system borrows heavily from France’s Napoleonic Code) have judicial systems that function very differently from ours

Perfect! When the Democrats are able to do so, they should 3 more seats to SCOTUS…

@Doug Mataconis:

Couple others that have commonality in that they are Constitution-based systems with ties to English common law:

South Africa 11

Israel 15

Oh, and I am pretty sure New Zealand has 6, not 5, on its Supreme Court.

Our next Democratic president should take the supreme Court up to 11.

That’s better than ten. It’s one more.

The supreme Court was specifically designed to maintain some stability, by insulating it to a certain degree from election outcomes. In other words, it was to be separated from the whims of the majority.

@Eric Florack: Right. That’s why Thief Justice Rehnquist called a halt to the Florida recount process in 2000, on the grounds that the state couldn’t be trusted to conduct the recount in accordance with the law, whereas the Supreme Court could look into the future and tell in advance what the results would be.

@SC_Birdflyte: given what we’ve seen out of Florida election officials subsequently, particularly Broward county, (Snipes for example) it would seem the supreme Court got that one right