Reshoring American Jobs?

After decades of exporting American jobs, corporations are bringing them home.

WSJ (“U.S. Companies on Pace to Bring Home Record Number of Overseas Jobs“):

U.S. companies are bringing workforces and supply chains home at a historic pace.

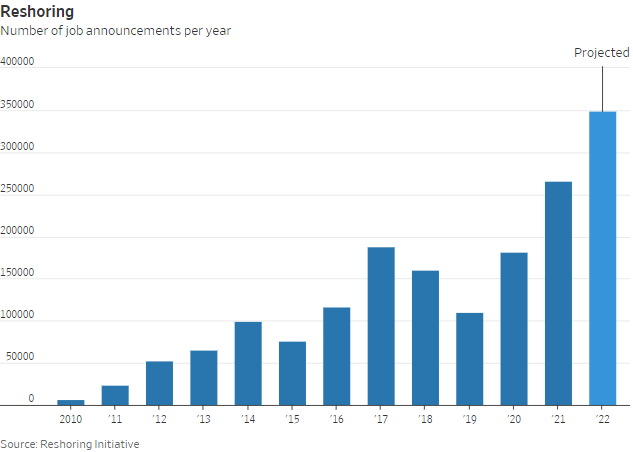

American companies are on pace to reshore, or return to the U.S., nearly 350,000 jobs this year, according to a report expected Friday from the Reshoring Initiative. That would be the highest number on record since the group began tracking the data in 2010. The Reshoring Initiative lobbies for bringing manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.

I’m always leery when news accounts are based on reports from lobbying groups. Perusing the Reshoring Institute’s website, I can’t quite figure out who they are, even though they’ve been around for a dozen years. Neither founder Harry Rosen nor the three other board members ring a bell. They have oodles of “sponsors,” none of which strike me offhand as nefarious. My cynical guess, though, is that there’s an interest in appearing to create American jobs to take off political pressure.

Over the past month, dozens of companies have said they had plans to build new factories or start new manufacturing projects in the U.S. Idaho-based Micron Technology Inc. announced a $40 billion expansion of its current headquarters and investments in memory manufacturing. Ascend Elements said it would build a $1 billion lithium-ion battery materials facility in Kentucky. South Korean conglomerate SK Group said it would invest $22 billion in a new packaging facility, electric vehicle charging systems, and hydrogen production in Kentucky and Tennessee.

“We think it’ll be a long-term trend,” said Jill Carey Hall, U.S. equity strategist at Bank of America Corp. “Before Covid there was…a little uptick but obviously Covid was one big trend and you’ve seen a continued big jump up this year.”

Emphasizing again that it comes from a lobbying group promoting “reshoring”—or, again, the appearance of it—here’s the data:

It’s also worth noting that, while “announcements” strike me as a reasonable way to track the phenomenon for recent years, it seems that, for most of this period, it would be more useful to track actual jobs moved back home.

To be sure, globalization has been a tailwind for investors and large companies for much of the past 30 years, particularly U.S. firms. Increased trade across borders boosted profits and productivity and allowed countries to focus on the goods and services they were best equipped to produce. Globalization has also provided multinational companies with new customers and new pools of low-cost labor.

But the Covid-19 pandemic, which snarled supply chains worldwide, pushed many executives to think about bringing their business closer to home. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which upended commodities markets, is another motivator. So is the possibility of a conflict between China and Taiwan, which produces the chips used in smartphones, personal computers and cars.

The U.S. government is also luring companies back. The Chips and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, both passed this month, provide tax breaks and other incentives for building and investing in manufacturing centers for goods such as semiconductors, electric vehicles and pharmaceuticals.

Investors’ increased focus on carbon emissions also has bolstered the need for closer-to-home supply chains. Carbon pricing mechanisms and taxes recently implemented in the European Union and elsewhere will further reduce the appeal of extensive cross-border supply chains, Barclays economists wrote in a recent note to clients.

The confluence of so many factors incentivizing having jobs in the US and other reliable democracies is what gives me confidence that it is indeed happening. It occurred to me very early in the pandemic that American companies should be rethinking Chinese investment in particular and the ensuing supply chain crises have brought to light the dangers of the distributed nature of our manufacturing system.

Barclays found that large S&P 500 companies are recruiting more in their home countries and slowing cross-border M&A activity.

“Globalization is in retreat,” the firm’s U.K.-based economists Christian Keller and Akash Utsav wrote.

The 350,000 reshored jobs expected this year would far exceed the roughly 265,000 jobs added in 2021 and would be more than 50 times the 6,000 jobs reshored to the U.S. in 2010. The Reshoring Initiative tallies company announcements of head-count increases for positions that were previously held in other countries, new positions in industries that had little to no U.S. presence and positions created in the U.S. from direct investment by companies based in other countries.

In other words, they’re likely grossly inflating the phenomenon by counting things that clearly aren’t “reshoring.”

On corporate earnings calls in the second quarter, the term “reshoring” was mentioned nearly 12 times as much as it had been in the second quarter of 2019, according to data from Bank of America.

That’s likely as much a function of new jargon taking hold as it is a meaningful measure of the phenomenon in question.

However, the broad shift might not be an outright win for blue-collar American workers. Increased capital spending suggests many companies could be looking to replace overseas workers with technology rather than with U.S.-based workers, according to Bank of America. Capital expenditures are often investments in equipment or technology that automate the tasks of workers.

“There’s no question that companies, when they bring jobs back, they know they’re going to be paying three to five times as much for labor,” said Harry Moser, the founder and president of the Reshoring Initiative. “Therefore they have to automate.”

North American companies ordered a record 11,595 robots, worth $646 million, in the first quarter, putting 2022 on pace to surpass last year’s record numbers, according to the Association for Advancing Automation.

I mean, we’re measuring announced jobs, not announced factory openings. Sure, to the extent it’s more efficient to replace people with equipment, companies are going to do that. But that means we need people to design, make, and maintain the robots.

I suspect that after substantial investment that won’t actually produce much in the way of results we’ll arrive at the conclusion that near-shoring is a more practical strategy in many cases than reshoring. I’ll believe that we’re bringing chip manufacturing back to the U. S. when I see it.

As I’ve said over at my place, we aren’t the only country making substantial investments in chip manufacturing. China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan are, too. Add Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia.

It is astounding just how many jobs can be replaced by machines. And with machine learning, if a company is willing to invest the time and capital, almost any job could go that route.

True, but those will be fairly high skilled and well trained people, so it is really not a solution to the jobs issue for the old industrial heartland. That re-shored industrial capacity will be automated has been baked in from the start, which is why the working class will again be disappointed.

What the working class is pining for, are jobs that pay like union jobs in the auto and steel industries of the 50’s/60’s and require little education beyond a high school degree, if that. That’s the promise that the working class is hearing, both from the industrialists and the politicians, and it won’t happen, again.

Does moving jobs from China to Mexico count as ‘re-shoring?’ Mexican workers beat Chinese workers in some measures of productivity – and shipping costs and shipping times are rather lower.

I don’t have any special understanding of where jobs are going, but when I visit manufacturing plants today there seem to be two types of hourly employees. People who are very low-skilled and keep the hoppers filled, empty and replace the various trim and waste bins, unstick jams and so forth. The primary reason they are still there is that humans are flexible. They do a couple of dozen simple but essential jobs. Every time there is a capital investment in a line it is basically expected that one or more of these positions will be eliminated.

The second type of hourly worker I see (and these are who I work with the most) are the highly skilled and highly knowledgable mechanics, electricians, PLC specialists, etc, who keep the whole place running. This is a highly specialized job and even smart engineers and programmers would have trouble with them. You need to know hundreds of pieces of equipment and dozens of different ways of troubleshooting and maintaining them. Many of them have their own maintenance and troubleshooting modes, all different, all idiosyncratic. You also have to have a diplomat’s or war planner’s skill set. You have to understand the relative importance of each piece of equipment vis a vis the dollar production they are responsible for, which lines can afford to go down for a day of maintenance and which ones need to get all hands on deck to get up and running. Which production orders, i.e. which customers, are most important that day. How to balance the demands of 50 management people, all with different priorities and all telling you that this or that is the most important thing for you to work on.

I’m working with a guy at a plant right now. Technically, he’s just an hourly worker and no one reports to him. Practically, he’s crucially important and if he says he needs this electrician or that mechanic to be doing something, then they are doing that thing. He is retiring next year and he has a retirement readiness plan, consisting of a checklist with hundreds of items that he wants to get resolved to insure his successor is only dealing with new problems, not old ones, as much as possible. This impacts us because there is something he doesn’t like about our equipment. Basically, every six months their Quality System calls for a certain performance measurement to be validated, and to take this measurement on our equipment requires it to be put into a special mode, alarms paused, and several settings changed. You confirm the measurement, and then have to undo everything to get it production ready again. It only take 15-20 minutes but it requires enough specialized knowledge that he does it himself. As part of his checklist he is insisting we make is so a line operator can do it from the main screen, and he’s holding up an order for three more units until it gets fixed. The buyers, the planners, the plant engineers will put their project on hold until he is satisfied. Multiply this by hundreds of different pieces of equipment in his domain, and you get a sense of why people say these new jobs are “highly skilled”.

Wanted: 7,000 construction workers for Intel chip plants

File under: Impediments to re-shoring…

@MarkedMan: I think I would be, as an early stage PE investor in industrial investments. Have learned to have a juandiced eye for the promises of machine learning in industrial settings. One day it will arrive, but skilled humans remain superior, even semi-skilled, for a wide range of functions, even if more superior when being (to use the otherwise horrid phrase) ‘tech enabled.’

On other hand the day is coming, within at least the under-40 lifetimes (if not my own, although it is possible) and needs preparation, which Anglo world approaches are fairly mediocre.

@MarkedMan:

This is of a match to my actual industrial (RE and logistics) investment experience

Skilled blue collar labour, not from a Uni education but from modernised technical. The German firms we work with have well-done programmes not just chez Germany but also in their subsidiaries. Good robust efficiency gains.

@Sleeping Dog:

A very American statement which at once rather discounts working class potential and misframes.

The semi-mythical 1950s-early 1970s era of untrained labour ‘aristorcracy’ of the developed world while in rebound from WWII is not something that is achievable as itself.

However to treat blue collar labour as untrainable to high skill (as this does in the end by implication) is to make a fundamental error, as MarkedMan post does reflect.

Older labour perhaps not retainable but as a focus for a whole cohort of youth which Anglo world thinks about rather excessively via the University route to the practical effective exclusion (other than lip service) of technical training for labour.

Even solar panels are executable in USA land (to examine an industry with which I am directly familiar), but needs an industrial approach that is more German than Anglo tradition, and not afraid of high-skilled labour (labour not engineers) investment and automation.

Effective industrial policy aimed at industry based apprenticeship programmes (and not for profit scamming training nor congenitally outdated and behind state centres) rather than writing off Uni debt for literature graduates would be a rather better play to undertake for you.

@Lounsbury:

Alas, US companies have shed the internal training of employees, pushing it back to the state and the scammers, and evidence that this will change is thin. Too often companies look at employee training as a cost that will result in the employee taking the developed skill to another employer. This will need to change, if apprenticeship programs are to become widespread.

They were doing that several years before COVID hit. I was seeing it back in 2015–starting in Hong Kong, and moving onto the Mainland.

China has become increasingly unfriendly to foreign companies (especially American ones). Financial companies started moving out of HK very early, as they saw what was coming. HK depended on freedom to let the financial sector do its thing. With the “Security Act” being handed down from Beijing, those companies have been proven right.

Factories were moving out as well, but they have to do it slower or risk losing major capital investments (e.g., machinery) and IP.

They’re not moving to the US, though. Most are going to Vietnam. Mexico is high on the list, and some areas in South America are attracting a few companies. Africa would be good for labor, but the lack of solid infrastructure and civil unrest throughout central Africa pulls them off the list.

This is (almost) all for manufacturing and other “low skill” jobs. The stuff coming back to the US (or expanding into the US) is high-end tech stuff. Factories aren’t going to pay UAW rates (and deal with the UAW negotiations) when they can set up a factory just over the border and pay a quarter the rate for people to push buttons on the injection mold machines.

@Sleeping Dog:

Old-school unions are starting to get in on this by setting up trade schools of their own. I’ve seen ones run by the Iron Workers, Boilermakers, and IBEW (there’s a joint trade school just down the road run by a coalition of unions). It’s a small dent, but it’s there.

@Sleeping Dog: And let’s just contrast that to what the Libertarian leaning civic leaders brought to Wisconsin. What happens when the “shrink government down until you can drown it in the bathtub” crowd is entrusted with civic development…

@Lounsbury:

Just to clarify, you think you would be what? We all know that you think you are many things–not the least of which is the final authority on all matters investment related as those investments impact the global economy. But what are you claiming to be specifically in this case?

@Mu Yixiao:

Re: Vietnam. Some success there, and I admit I’m not completely current, but some years back a number of manufacturers were making the jump, only to find that Vietnam was more like a normal developing country than a China. Promised roads weren’t built, power was spotty, labor was unreliable. Interestingly, a fair number of companies opening up plants there in the hopes of finding cheaper labor were Chinese. And while Mexico is still thriving, my experience with plants there in a number of industries is that they are the “problem child”, requiring frequent interventions from corporate, and essentially acting as the juniors to the engineering and maintenance teams to their US or European based counterparts. Not a surprise, since the relentless focus on keeping down wages, coupled with the realities the type of highly skilled personnel I described above means that such individuals can make a lot more by setting themselves up as a contractor servicing those plants than by working for them directly.

@Sleeping Dog: Yes. It is a broad developed Anglo-world issue not merely an American one

But one has to start somewhere rather than pining for an ideal state, and so an industrial policy that provides direct or indirect (or both) incentives may be a place to start, and a better one than protectionism. Tax and rebate incentives plus oversight. Perhaps broad funding for PPP investment partnerships in this area, it has worked in developing markets. But there does need to be some significant end-user engagement else such things rapidly become obsolete.

@MarkedMan: while the inverted Bolshevism of the US Libertarians is indeed problematic, that article seems rather more an example of Trump-like general bungling and precedence of PR over planning than anything Liberterian as such.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: I think I would be an internet blog commentor trying to type in too small and extremely twitchy comment boxes under a semi-broken comment plug-in. Else I would be someone with some direct multi-company experience with investment in higher-skilled labour as a strategy.

@Mu Yixiao: Trade union schools alone have a rather strong tendency to focus not on where things are going but to the ideal state for the trade union historical labour membership.

While of course there are interest and governance issues, industry entity training with strong budgetary implication from the backers has stronger incentives to be focused on the future.

@Sleeping Dog: “Too often companies look at employee training as a cost that will result in the employee taking the developed skill to another employer. This will need to change, if apprenticeship programs are to become widespread.”

Indeed. My brother is a big guy for arguing that “the schools should be more involved in getting people into the trades.” While I agree with him, I’ve been in education for 30 years and no one has been begging for the schools–or anyone else for that matter–to load up apprenticeship programs, or even start any. There’s lots of complaining about shortages of skilled workers, but even those are of the “we need 7000 builders right now and don’t have ’em” sort represented in Ozark’s first post from this morning’s forum.

If only we could train people, hold them in suspended animation, and then thaw and refreeze them as required. That would be perfect! (And bring a bigger ROI.)

@Mu Yixiao: @Mu Yixiao: When my father first came to the US in 1950 he worked on a farm in Ohio, but soon got talked into moving to Chicago and becoming a plasterer by the US family patriarch, his Uncle Joe. My father was very proud of his apprentice program training as a plasterer. Ever see a plastered ceiling with swirls? My father could walk into a room, spend 15 minutes making mental calculations and end up with perfect 3/4 circles, ending precisely at the ceilings edge in both directions even if the room wasn’t perfectly rectangular. (I’m embarrassed to link to that picture. My father would never do such a horrible job.). If you ever find yourself in Union Station in Chicago, you might look up and see some of his work, although it’s been 3 or 4 decades since he was on the scaffolding there (and he’s been under the ground a decade.) I remember him explaining that the molds were lost a century ago and he had to find the best preserved examples of each and make new molds from them.

Anyone who thinks laborers are “common” and “uneducated” is woefully ignorant.

@Lounsbury:

Fair enough. I was basing my “Libertarian” comments on a few extended reportings of the fiasco, especially an excellent one in the “Reply All” podcast, in which they interviewed some of the “geniuses”, who were obviously parroting the Koch Brothers/“Reason” magazine ( but I repeat myself) school of libertarianism.

@MarkedMan:

And my grandfather was a stone mason who built castles and “keystone” bridges. He was a peasant, and never went to school. When he came to the US he dug potatoes for two years and ended up working in a factory. Yes, he was common and uneducated (in the modern sense).

“Educated” has a common meaning of “attending college or beyond”.

@Lounsbury: I would think it bad form to blame ” twitchy comment boxes under a semi-broken comment plug-in” for the fact that I struggle with writing complete sentences, but YMMV, and thank you for the clarification. I can see how that long descriptor could get partially, or completely, elided for someone as busy as you are. It’s easy to mistakenly presume that people have adequate background about oneself.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

20 or so years ago I had a solo rep agency in StL, every couple of weeks I’d have breakfast, lunch or a beer with a few other guys who had small agencies, mostly marketing or web development, nobody had more than 12 employees. The most frequent complaint they had was the difficulty in finding young, talented people that could create on their own. They all could find people who could complete a task, if told what to do, but not a project. One guy went to the point of refusing to take interns unless they were matriculating from U of M/UM StL, Wash U or SLU. His claim was those were the only schools that taught their grads how to think. On the other hand, I was acquainted with a guy who ran a marketing group at AB and he was perfectly happy with drones who were satisfied with executing the ideas of others.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: given on my smart phone brick the comment box is tiny, comparatively hard to use as compared to others I type in on a phone, I shall stick with it as a perfectly valid partial justification. It is true however, I have a tendency to start a new thought in writing before finishing the last, which is not helped with tiny, twitchy comment box of an oft-not-functioning properly plug-in (although this is not more than observatio n, I don’t expect the bloggers to bother to spend real money on a free site).

@MarkedMan: understood, does not emerge from that particular article although the Trumpish bungling and precedence of PR over actual hard work to make projects happen does. It would not surprise to find some kind of symbiosis between the two.

And…. Ford just announced it’s cutting 3,000 jobs (though not all in the US).

@Lounsbury: I feel your pain on that point. I simply don’t write comments longer than a few words when I’m reading from my phone. I simply can’t manage to write longer comments–or at all for that matter.

And please feel free to wish that I came here on my phone more often. I’m sure many people do. Luddite suggests that I begin training the voice-to-text feature on my phone, but so far, I don’t see the point.

My college just added a training pathway (certificate through AAS) in Mechatronics – essentially the work done by the fellow MarkedMan discussed, focused on robotics and automation. That is on top of existing recently added pathways that culminate in an AAS in Lab Science (to support the Fujifilm Biotech manufacturing facility in town), Construction Management, Welding, Facility Management, HVAC, Surveying Technician, etc. All of them have an established pathway with a four-year partner to a BAAS for those who choose to move into management functions.

The reason that I’m making this comment is point out that this training does exist here, and it exists at the community college level, with appropriate levels of tuition. In many instances, the Texas Workforce Commission will pay for some or all of the training costs, and some of these programs have a waiting list. Folks absolutely do not have to go the private for-profit trade school route and deal with places like Corinthian and Kaplan and ITT Tech.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

My record for posting to OTB from my phone was in May 5th 2021, when I was waiting in line for the first dose of Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

In order not to go completely off-topic: what’s needed isn’t so much to restore jobs to America, but to restore the souls of large employers.

@Kathy:

Restore?!!! Try googling “Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire”. Or, and this long precedes everything being available on the internet so you have to go back into time, the discussion I once heard on a Georgia call in radio show where one guy was railing against “mindless government regulation” in the length of the construction code for employee bathrooms and how it defied common sense. A few callers later it was an elderly gentleman who turned out to be the actual mindless government regulator who had written most of it. It turns out it was all because of a years long battle between him and the owner of a bunch of North Georgia factories (for those familiar with North Georgia factories, I can hear a collective “uh huh” of recognition). New code called for all factories to have restrooms for all the workers, not just the front office, and the owner didn’t want his employees getting above their station and getting ideas, and so they could go in the field behind the factory like their parents and grandparents did. They didn’t even have outhouses. What followed was lengthy back and forth full of incidents where the owner nailed an old coffee can to a post and declared it a urinal, and the regulator tried to put an end to that in the next revision. Back and forth, back forth, every regulation fought every step of the way and thousands of hours and dollars wasted in court cases.

I’d guess most of it is hedging. Some have realized being completely dependant on the political situation and supply chains in other countries over which they have little or no direct control carries potentially game-over risks for their company. So might a change in domestic political winds that all but mandates domestic manufacture. Difficult to make predictions, especially about the future… Having at least some domestic production capacity provides a life-boat should shove come to push. Expanding plant capacity is much easier than creating if from scratch.

As long as being price competitive remains an imperative they are forced, to some degree, to be predominantly off-shored.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: I would wish no such thing. The comments, even those I rather fundamentally disagree with and criticise, typically are my source of entertainment here.

@Kathy:

And the Soviet New Man. Or maybe another mythical goal mistaking intellectualised idealisation and abstractions for real things with call backs to mythical pasts that never existed.

Large enterprises are nothing more than collections of humans in a bureaucratic structure. They respond to their incentives, as any collective of semi-organised over-clocked chimpanzees do.

If one wishes to effect some change in large enterprise (although large enterprises are a minority of both firms by number and firms by employment so really just are visible proxies), or medium sized enterprises, one has to not engage in pious inanities and Soviet New Manism, but address incentives. Not pious inanities.

In the case of Anglo world enterprises, that may include addressing an excessive over-interpretation of the shareholder value concept that has been over-interpreted into an excessively short-term quarterly revenues focus via the incentives that also reward such.

@Mu Yixiao: Hq and contract salaries.

Financial Times