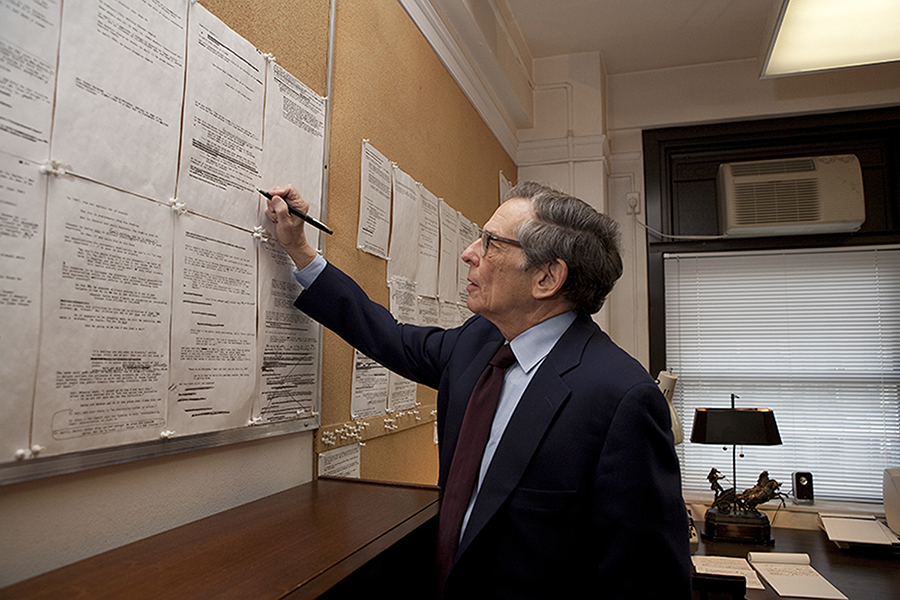

Robert Caro on Writing

The esteemed biographer on his process.

David Marchese has a wonderful interview (“Robert A. Caro on the means and ends of power“) with the author in the New York Times Magazine. There’s a lot in there and I encourage you to read it in its entirety. Caro’s reflections on his writing process are particularly interesting.

I know that when you’re planning your books, you write a couple paragraphs for yourself that explain what the books are about, and then you use those paragraphs as a North Star to guide your writing and outlining. Yes.

What if you have great material that you can’t make fit into an idea expressible in those two paragraphs? Does having them box you in at all? It’s the opposite. Let’s take “Master of the Senate.” I had two paragraphs that explained that I was writing about power, and that the form of power I wanted to write about was legislative power. More specifically the book is about how a guy, Lyndon Johnson, rises to power in the Senate and then for six years makes the Senate work. And the other half is of it is what he does with that power. Well, he passes the first civil rights bill in 82 years. I’m telling you my train of thought here.

Yep, I’m with you. So there’s this character, Senator Richard Russell. He’s fascinating because he’s so smart, he’s so learned. In foreign affairs he’s like a consul of Rome. He sees the whole world, you know? But he’s this son of a bitch.

And a racist. Yes. Here’s how I boiled that book down: I said that two things come together. It’s the South that raises Johnson to power in the Senate, and it’s the South that says, “You’re never going to pass a civil rights bill.” So to tell that story you have to show the power of the South and the horribleness of the South, and also how Johnson defeated the South. I said, “I can do all that through Richard Russell,” because he’s the Senate leader of the South, and he embodies this absolute, disgusting hatred of black people. I thought that if I could do Russell right, I wouldn’t have to stop the momentum of the book to give a whole lecture on the South and civil rights. What I’m trying to say is that if you can figure out what your book is about and boil it down into a couple of paragraphs, then all of a sudden a mass of other stuff is much simpler to fit into your longer outline.

[…]

But where does that come from? And why do you pursue the answers with such tenacity? It’s a very good question. It has always been a part of me. When I first went to Newsday and was a beat reporter, I couldn’t stand writing stories when I still had questions left to answer about them. So where does that come from? It’s just a factor that I’m not able to stand up against. People don’t understand: If you’re doing a book, and you say, “I’m going to show what one mile of highway really is,” you’re saying that you’re going to spend six months of your life doing that. That’s six months where you’re not going to produce any writing, and if the final result isn’t in the book, no one will ever have known. Your conclusions can even still be the same without it. But what would be missing is that you wouldn’t have made people see the human cost of that mile of highway. I’m getting away from your question, which is where it comes from: I have no idea. I don’t necessarily think it’s a good thing.

Why not? I would like to have written more books. I’d like to finish this last Johnson book. But it’s the element of time — you’re always thinking no one will know if the thing you’re working on isn’t in the book.

You say everybody knows about blacks not being able to vote in the South, so you don’t have to go into that. But I’d remembered coming across testimony from the Civil Rights Commission and I went, This is horrible. A sense of anger boils up, and it leads you to say, “What was it like if you tried to register to vote?” Don’t just say, “It’s hard.” What was it really like? You think you understand how hard life is in the South because you’ve seen movies about it. But then you learn about a guy who wanted to vote, Margaret Frost’s husband, who sees someone drive to his house and shoot out the light on the porch. He was going to call the police but then saw it was a police car driving away from his property. It was like the Jews in Nazi Germany: There was no place for these people to turn. So, do you want to write the book without showing that? The answer is no.

There’s a part in “Working” where you say don’t like to give “psychohistory” in your books. But obviously you get into the psychology of the people you write about. So can you explain what you mean there? If I feel that a driving force that influenced Lyndon Johnson’s entire life was his relationship with his father, I can either talk about that in psychological terms or I can show it. I want to show it.

[…]

Not to be morbid myself, but how does it hamper the work you have left to do when so many of the sources you’ve relied on are no longer alive? I was just saying to Ina that there used to be a group of people I could go back to with questions and now I can’t. Soon I’m going down to Austin on my book tour, and it’s poignant, because I used to know everybody — It was 30 or 40 people, and they became my friends over these years. Now every one of them is dead, and it’s as if I’m left to tell their story. I go to Austin, and there’s not one person left, and I’m getting old.

Are you well-situated with the material you’ve already compiled to be able to finish the last L.B.J. book the way you want to? This happens to me every day: There are questions I should ask, but the people aren’t here to ask anymore. I mean, Joe Califano is alive. Larry Temple, he’s alive. Tom Johnson, too. There are a few. But dramatic things happen. George Christian, who was Johnson’s White House press secretary, he attacked my first two books. I had tried to talk to him, and he basically sent word to me to go [expletive] myself. Then I heard that he had lung cancer. He had chemotherapy but recovered, and then the cancer came back. One day he calls me out of nowhere and says “I guess it’s time for me to talk to you.”

Death is a motivator. Yes. I had three interviews with him. The first time I was talking he had an oxygen mask on his desk. The second time he had to use the mask. Then the third time he was using the mask the whole time, and suddenly he said, “I guess you’ll have to get the rest from someone else, Bob.” Then he called for his chauffeur. A short time later he died. I use him as an illustration of the people who ultimately wanted to help me understand Lyndon Johnson and the vanishing world of Texas politics.

[…]

What other tricks like that have you learned? Lyndon Johnson used to say to his aides, “What people tell you with their eyes and hands is more important than what they tell you with their mouth.” And he would also say, “There’s always something the other guy doesn’t want to tell you, and the longer the conversation goes, the easier it is to figure that out.” And you want to know something that’s not a trick? You have to interview people over and over again. I did 22 formal interviews with Johnson’s speechwriter Horace Busby. If you look through these interviews, you say, “Boy, what he’s telling you about something in the first interview isn’t what he’s telling you about that same thing in the 10th interview.”<

[…]

How do you feel about the fact that the L.B.J. books, even more than “The Power Broker,” have turned out to be your life’s legacy? Surely you never expected to be writing about Lyndon Johnson in 2019. It’s boastful to talk about, but you feel that these books will endure. “The Power Broker” is 45 years old. I ride the No. 1 subway a lot, and when I see Columbia students reading “The Power Broker” on the subway — you feel you’ve accomplished something. You feel what you’ve learned is worthwhile. Same thing with the Johnson books. You feel good about that. At the same time, I’m going to feel bad if I don’t finish them.

In your heart of hearts, how confident are you that you will? People want to make me think about that, but it is a mistake to think about it, because it would make me rush. It’s probably the understatement of all time, but I have not rushed these books. They’ve taken the amount of time that’s necessary to show what I wanted to show. What would be the point of the books if I didn’t do them properly? I’m trying very hard to keep the standard of this book up to whatever standard I had in the other ones.

Do you have a title for the last book?I do.

Will you tell me what it is? No.

I don’t know if you recall, but this magazine ran a profile of you around the time that “The Passage of Power” came out. That article suggested that maybe on some level you don’t want to be finished with the Johnson books. Does that ring true? That’s ridiculous. You couldn’t want anything more than I want to be finished with this book. At the same time, it’s important not to rush it. But you asked me how confident I am that I’ll finish. Well, of course I’m not.

One can only hope.

Classic POV question. Who is telling the story? Why that person? It’s a bit more complicated in fiction because our job involves restricting the data flow while Caro gets to take the God’s Eye view. IOW fiction writers don’t want you knowing everything, just what we want you to know, and in the order we prescribe. But it’s still the same question, who is my vehicle for telling the story. Interesting.

Also interesting to realize that he has to pick a through-line, a trunk to support all the various branches. He’s still telling a story but one where he aspires to tell it all, using reality the way a good photographer does – capturing as much truth as he can get in the shot, but then still developing and tweaking so that we end up with something engaging.

Caro also follows fiction rule #1: it’s about characters, not events. Characters in events, but always character first. I’ve thought of trying my hand at non-fiction but honestly it’s just so much easier to make sht up.

I’ve written fiction (mostly) and non-fiction books, and there advantages and drawbacks to books. On the fiction side, as Michael notes, the big plus is that you get to make up everything, which is enormously liberating. Of course, that’s also the downside, because it’s a fair amount of work to create the characters who drive the story. The upside of non-fiction is that the story and characters already exist, so it’s work already done for you, in a sense. Of course, non-fiction entails a lot of research–which is fine with me, because I like doing it.

Either way, it’s the most fun you can have with your clothes on. I wouldn’t have done it otherwise.

@CSK: In my first sentence, I meant to say: “there are advantages and drawbacks to both.”

@Michael Reynolds:

Have you considered writing books like Trumponomics? Then you would get to use the structure of non-fiction while still just making shit up.