Science Fiction Great Harlan Ellison Dies At 84

Harlan Ellison, who had a reputation for being as cantankerous as he was a great writer, has died at the age of 84.

Harlan Ellison, an incredibly prolific Science Fiction author who was also responsible for the most well-known episode of Star Trek during its original run, has died at the age of 84:

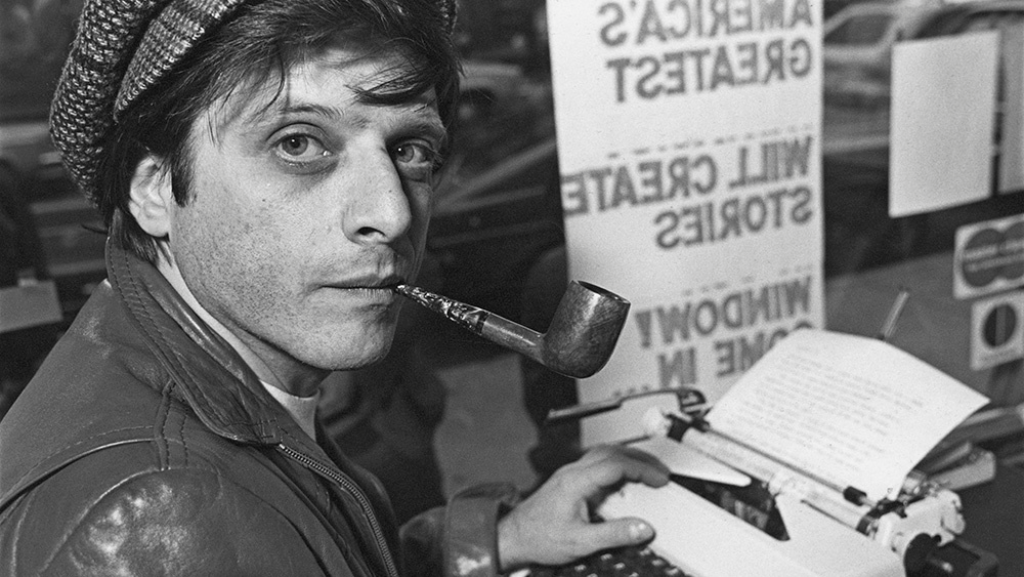

Harlan Ellison, a furiously prolific and cantankerous writer whose science fiction and fantasy stories reflected a personality so intense that they often read as if he were punching his manual typewriter keys with his fists, died on Wednesday at his home in Los Angeles. He was 84.

His wife, Susan Ellison, confirmed his death but said she did not know the cause. He had had a stroke and heart surgery in recent years.

Mr. Ellison looked at storytelling as a “holy chore,” which he pursued zealously for more than 60 years. His output includes more than 1,700 short stories and articles, at least 100 books and dozens of screenplays and TV scripts. And although he was ranked with eminent science fiction writers like Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov, he insisted that he wrote speculative fiction or, simply, fiction.

“Call me a science fiction writer,” Mr. Ellison said on the Sci-Fi Channel (now SyFy) in the 1990s. “I’ll come to your house and I’ll nail your pet’s head to a coffee table. I’ll hit you so hard your ancestors will die.”

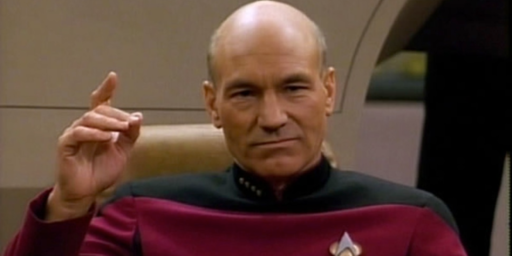

Mr. Ellison’s best-known work includes “A Boy and His Dog” (1969), a novella set in the postapocalyptic wasteland of the United States; “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” (1967), a short story about a computer that tortures the last five humans on earth; “The City on the Edge of Forever,” a beloved back-in-time episode of the “Star Trek” television series in 1967; and ” ‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman” (1965), about a futuristic society where time is regimented by a fearsome figure called the Ticktockman.

“But no one called him that to his mask,” Mr. Ellison wrote. “You don’t call a man a hated name, not when that man, behind his mask, is capable of revoking the minutes, the hours, the days and nights, the years of his life. He was called the Master Timekeeper to his mask.”

Mr. Ellison was a fast-talking, pipe-smoking polymath who once delighted talk-show hosts like Merv Griffin and Tom Snyder with his views on atheism, elitism, violence and Scientology.

And he could be wild, angry and litigious. He said that he lost his job with the Walt Disney Company — on the first day — when he stood up in its commissary (with company executives watching) and described how he wanted to make an animated pornographic film starring Mickey and Minnie Mouse.

He is said to have sent a dead gopher to a publisher and attacked an ABC executive, breaking his pelvis.

He frequently accused studios and television producers when he believed they had copied his stories. One of his many lawsuits included one against the makers of the movie ”The Terminator,” which accused them of plagiarizing “Soldier,” a script he wrote in 1964 for the television series “The Outer Limits.”

More from Variety:

Speculative-fiction writer Harlan Ellison, who penned short stories, novellas and criticism, contributed to TV series including “The Outer Limits,” “Star Trek” and “Babylon 5” and won a notable copyright infringement suit against ABC and Paramount and a settlement in a similar suit over “The Terminator,” has died. He was 84.

Christine Valada tweeted that Ellison’s wife, Susan, had asked her to announce that he died in his sleep Thursday.

The prolific but cantankerous author famously penned the “Star Trek” episode “City on the Edge of Forever,” in which Kirk and Spock must go back in time to Depression-era America to put Earth history back on its rightful course, a goal that for Kirk means sacrificing the woman he loves (played by Joan Collins). The final script was rewritten by “Star Trek” staffers, leaving Ellison unhappy.

His 1995 book “The City on the Edge of Forever: The Original Teleplay That Became the Classic Star Trek Episode” contained two drafts by Ellison.

The author was still steaming over his experience more than four decades after the episode originally aired: In 2009 Ellison sued CBS Paramount Television seeking revenue from merchandising and other sources from the episode; a settlement was reached six months later.

The author of a 1980 L.A. Times profile declared, “Ellison is fiercely independent, proudly elitist, frequently angry, tenacious and downright vengeful.”

Talking about the Hollywood establishment, Ellison told the author, “They’ve got to know that everybody isn’t frightened and won’t back down…. These people are not creators; they belong to the AAA — agents, attorneys and accountants. They aren’t comfortable dealing with writers — they think we’re madmen. They’re really only comfortable dealing with numbers.”

In a separate case, Ellison won $337,000 (later reduced a bit in a settlement) from ABC and Paramount Studios in 1980 for copyright infringement on a short story the author had penned with Ben Bova, “Brillo.” Ellison and Bova had been asked to develop it at ABC, but the option there had lapsed; Ellison then showed it to Par execs, who said they weren’t interested. ABC aired a Par-produced telepic called “Future Cop” in May 1976 and later a brief series of the same name. The premise, about the first android policeman, was identical to that in “Brillo.”

(…)

Born in Painesville, Ohio, Ellison grew up in the only Jewish family in a small town where he said he had to defend himself in physical altercations on a daily basis. During the 1950s Ellison attended Ohio State U. for 18 months, served in the Army and began to sell sci-fi stories to pulp mags.

He moved to California in 1962.

Ellison was famously fired on his first day of employment as a writer at Walt Disney Studios after making highly irreverent suggestions about the company’s beloved characters.

He penned scripts for “Route 66,” “Burke’s Law” and “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,” “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.” and even “The Flying Nun.” For a 1964 episode of “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour,” “Memo From Purgatory,” he adapted his own nonfiction memoir about having joined a street gang in Brooklyn.

Ellison also penned the screenplay to tepidly trashy Hollywood melodrama “The Oscar,” and the post-apocalyptic cult classic “A Boy and His Dog” (1975), starring a young Don Johnson, was based on an Ellison novella.

Ellison was also editor of the very influential sci-fi anthologies “Dangerous Visions” and “Again Dangerous Visions.”

When he dealt with Hollywood, he fearlessly said exactly what he thought again and again — often causing fallout as a result. In the wake of the 1977 release of “Star Wars,” a Warner Bros. executive asked Ellison to adapt Isaac Asimov’s short story collection “I, Robot” for the bigscreen.

Ellison penned a script and met with studio chief Robert Shapiro to discuss it; when the author concluded that the executive was commenting on his work without having read it, Ellison claimed to have said to Shapiro that he had “the intellectual capacity of an artichoke.” Needless to say, Ellison was dropped from the project. Ellison’s work was ultimately published with permission of the studio, but the 2004 Will Smith film “I, Robot” was not based on the material Ellison wrote.

Perhaps Ellison’s most famous story not adapted for the screen was 1965’s “Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman,” which celebrates civil disobedience against a repressive establishment. “Repent” is one of the most reprinted stories ever.

In September 2011, however, Ellison sued to block the release of New Regency’s thriller “In Time,” starring Justin Timberlake, claiming that the film hews too closely to “Repent,” then dropped the suit. In the early 1970s, Ellison created his only TV series, the Canada-produced “The Starlost.” He was so unhappy with the changes made by producers, however, that he took his name off the skein, which aired in 1973.

Ellison was a creative consultant for the 1980s edition of “The Twilight Zone,” for which he wrote several episodes, and was conceptual consultant for the 1990s sci-fi series “Babylon 5.” He also appeared in several episodes.

While notoriously cantankerous, Ellison was an extraordinary writer who seldom disappointed in the stories that he told, and he was able to tell many of them during his long career. For people who haven’t read much Science, or I should put it Speculative, Fiction, his name probably isn’t as familiar as those of other greats such as Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Arthur C. Clarke, but as someone who grew up reading everything I could find in that genre I’d have to say that he ranks right up there with the other greats of the field even if he didn’t achieve their fame outside the field. Even among non-genre fans, though, his work is at least somewhat known given that The City On The Edge Of Forever is one Star Trek episode that even non-fans are aware of in some way or another. So, even though the final script for that episode was changed from what Ellison intended, his work is remembered in some respect. In any case, while Ellison is gone, his writing will survive his passing so in some sense he’ll always be with us.

Yesterday I added Harlan to The List. Next time I’m at the liberry Ima see what they got.

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream

If you ever run across a copy of “Cooking Out of this World” (a collection of recipes and food-related anecdotes by a huge number of SF writers) there’s a very funny story told by Larry Niven about an encounter he and Harlan had at a science fiction convention. Involves a lot of dry ice, cherry brandy, a Hugo award, a side bet, and Harlan being Harlan.

“Don’t tell me this guy doesn’t hold a grudge!”

I don’t think Bradbury ever identified as a “science fiction writer” per se either. Some of his works are sci-fi, others are fantasy, and others (such as Dandelion Wine) are neither.

In any case, “speculative fiction” is simply an umbrella term for sci-fi and fantasy, but the term isn’t that well-known to general audiences. In most bookstores and libraries, “science fiction” essentially means speculative fiction, and the section with that label includes everything from Asimov to Tolkien.

Harlan is a great cautionary tale. A man of tremendous talent who has barely turned out a word of fiction in decades after being one of SF’s most powerful forces in the 60s and 70s — essentially because he consumed all his energy, creative and I assume otherwise, in a constant stage of rage at, well, everything and everyone.

Harlan essentially wasted decades of his life in petty squabbles about major outrages about things he couldn’t change. That’s why all the great stories that get mentioned in the obits all come from the mid-60s.

@wr: I’ve not read much of his stuff but i’ve watched five or six interviews with him. He reminds me of me when I was young and self-righteous and angry. Fortunately after some, shall we say, Negative Social Interactions in my early 20’s I got a better sense of perspective and chilled out.

I’ll always be grateful to Ellison for this: Pay The Writer.

@wr:

Out in book land we don’t have a union and we are frequently asked to work for free, or even do things that lose us productive time and therefore money. Ellison’s rant was like a dose of Hollywood steroids for me. I immediately thought: hell yeah, get paid.

But he forgot what every writer ought to know which is that the best times in your life are when you’re working. Writing is your happy place, even if you’re miserable, it’s where you are meant to be. His brain didn’t stop working, so decade after decade he was still generating ideas, but he refused to write them down. That feels like spite and that’s not a good lasting impression.

@Michael Reynolds:

Did he not write–or was it that, after a point, no one wanted to publish him? This is no reflection on his talent; it’s a question of money. The fourth bestselling writer of all time is Danielle Steel, and she’s currently the bestselling writer alive. The woman writes crap. But she makes a lot of people a lot of money, including herself.

@CSK:

Someone would publish him, maybe not at a price he liked. But with his name recognition he could successfully self publish.

@Michael Reynolds:

I think he would have regarded that as beneath him, and I wouldn’t blame him.

Read this. It makes me glad I no longer teach writing.

https://psmag.com/education/the-secret-to-being-a-successful-writer

@wr:

I don’t know if you could say those decades were “wasted.” After all, Pay the Writer might have been considered one of those “petty squabbles” at one time.

This would be my explanation for why all the great stories mentioned are from the 60s and 70s: There was an actual short story market back then, plus the genre he was working in was undergoing a revival away from the Gernsback stuff to something more serious and literary. He was the right guy at the right time.

And then he wasn’t. Times change. Harlan stayed the same.

@CSK: His Wikipedia article shows production of similar rates (on cursory inspection) from the 60s through the 90s and into 2014. It may be that the impact of his later writing was limited by medium selection or that later publishers didn’t market him as well or that later in life, he was no longer considered “edgy.” But it appears that he kept writing throughout his life.

@CSK: As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, amen.

ETA: It does remind me of a story about Peter Frampton correcting a journalist to the notion that rather than being a “rock legend,” he was simply “the guy at the front of the line when an A & R guy walked by looking for the next big thing.”

@Michael Reynolds: Amen, brother.

@CSK: I teach writing, have watched many students go off to success, and I can say this guy is an idiot. It’s like he’s just discovered that having a powerful friend or being the kind of person who “they” are looking for is a major help in a career — and he doesn’t realize that it’s not just in writing, it’s in any career, ever in the history of mankind.

But the one that really pissed me off was “get lucky.” Because yes, every successful writer does at some point get lucky. But lots of unsuccessful writers — and people in other positions — get the same luck and they can’t do anything about it because they haven’t put in the years preparing.

It’s like when people (inevitably) want to know how I got my break or landed my first agent or whatever. The answer is that for me, just like for almost everyone else, it’s an unrepeatable sequence of circumstances and coincidences. But everyone I know of who has made it has their own freakish set of circumstances — and what they all had in common was that when someone asked to read their work they had a lot of great scripts ready to show. All the luck in the world means nothing without that.

@wr:

It was easier when I started out. But let me tell you about my all-time favorite rejection, which my agent read to me over the phone in disbelief, contradicting the normal practice of agents, which is simply to say the editor “passed” on it: “This book is too well-written to be commercially viable.”

@wr:

That’s actually nice to hear. I thought it was just me, but every time I get that question I want to start out, “Once upon a time the DNA gods said ‘let’s give this one a facility for language.'” The path I took is not the one open to anyone else. I sometimes resent the question. I fought may way through the thorns and you think I’m going to just push them aside for you? I couldn’t if I wanted to, but why would I want to?

For me ‘how you broke in’ is number two behind ‘what’s your inspiration.’ No one ever asks how to get better at their job. No one ever asks, ‘how do you build a good action scene,’ or, ‘what’s the balance between lifelike dialog and necessary exposition,’ or, ‘can we talk paragraph length?’ It’s always ‘the big break.’

@Michael Reynolds:

“Where do you get your ideas?”

It’s well-intended, but…where do they think I get them?

@Michael Reynolds: If you’re ever bored sometime and in the mood to type, I’d rather enjoy it if you elaborated on what you said the other day about ‘moves’ China Mieville makes. I haven’t read any of his stuff, but I’m always interested in hearing experts break down what’s really going on in a performance, because as a layman I miss things they can easily point out.

@teve tory:

Mostly I’m thinking of Miéville’s world building. It is so granular, so detailed, so utterly uncompromisingly original. There’s never a moment when he lets up and just plugs in some easy reference. It’s all so disciplined and demanding. Dude’s got an A+ imagination and A+ as well for discipline and technique.

On the flip side he cannot write character worth a damn, and his plots wander into the weeds and tend to sort of peter out. I’m better at both of those things, but when it comes to world building I’m pretty good, but I’m not China Miéville good, and I know it. In part it’s that I always keep an eye on the market and on the reader, so I compromise and take short cuts. But it’s also that his imagination machine is simply bigger, better and has more horsepower than mine.

Let me give you an example. Miéville works out the economics. What are the economics of Star Wars or Lord of the Rings? How do Jedi make money? Who pays Aragorn’s bills? He worries about that, he figures things like that out, even if you don’t see it on the page you feel the weight and the depth of his world-building.

@teve tory:

An addendum:

It’s very hard to surprise me in fiction. 90% of the time I see all the moves coming, an occupational hazard, but there’s fun in that, too, if I’m watching someone very skilled. For example, I saw the beats coming in BLACK PANTHER but the sheer skill with which it was written amazed me. But I love it even more when someone outwits me, tricks me, shows me something genuinely surprising. At times like that I get to be a regular reader/viewer. Danny Glover’s ATLANTA does that for me, I have no capacity to anticipate, I just have to ride along like everyone else. Mieville’s New Crobuzon books are like that, a constant stream of, “Whoa, cool!”

@Michael Reynolds: “He worries about that, he figures things like that out, even if you don’t see it on the page you feel the weight and the depth of his world-building.”

I found Perdido Street Station in a London bookstore probably in 2000 or 2001, bought it after reading a paragraph (to be fair — hooked by a great cover) and was awestruck. Don’t think I could compare it to anything except Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast, although they are completely different in tone, style and story. Same unbelievable strengths in world-building and similarly idiosyncratic approaches to plot and character.

@Michael Reynolds: “For example, I saw the beats coming in BLACK PANTHER but the sheer skill with which it was written amazed me.”

Pretty much how I felt about Infinity War. Had to see it a second time in theaters because the first I was so blown away by the skill involved in bringing together all those characters and storylines and making it all feel so organic that I couldn’t really focus on the experience of the story. Such a huge creative undertaking, and they make it look easy…

@wr:

This is the kind of stuff only writers notice. Everyone else comes out of a movie talking about the actors or the FX. Writers walk out thinking, “half a dozen ‘lead’ characters, backstory for each, and all playing important parts in on the denouement? Respect.”

@Michael Reynolds:

That’s actually my favorite thing about Neal Stephenson. He goes into great depths about geeky logistics.

@Michael Reynolds: When I’m teaching new writers, they all go through a phase when they despair because they’re not enjoying movies as much as they used to — that now all they could see was the mechanism. I always tell them to wait… because I know this passes. Or rather, this type of appreciation gets integrated into our aesthetics, so that we are able to see both the story and what goes into the story — in the same way a chef can appreciate a brilliant dish while at the same time understanding what ingredients went into it, or a painter able to see both a beautiful image and the brushstrokes that define it.

I will always remember seeing “Edge of Tomorrow” and being entirely wrapped up in the narrative — while at the same time being aware that it was brilliantly structured. It doesn’t hurt our enjoyment — it makes it richer.

Speaking of Miéville, The City and The City — mindblowing.