Supreme Court Agrees To Hear Case On Partisan Gerrymandering

The Supreme Court has agreed to hear its first case on partisan gerrymandering in more than ten years, but opponents of the practice shouldn't start celebrating just yet.

The Supreme Court agreed today to hear the appeal of the State of Wisconsin from a lower court ruling that struck down the states redistricting map on the ground that it went too far in drawing district lines that favored one party over the other:

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court announced on Monday that it would consider whether partisan gerrymandering violates the Constitution. The case could reshape American politics.

In the past, the court has struck down election maps as racial gerrymanders that disadvantaged minority voters. But it has never disallowed a map on the ground that it was drawn to give an unfair advantage to a political party.

Some justices have said the court should stay out of such political disputes entirely. Others have said partisan gerrymanders may violate the Constitution. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy has taken a middle position, and the case could turn on his vote.

In a 2004 concurrence, he wrote that he might consider a challenge to political gerrymanders if there were “a workable standard” to decide when they crossed a constitutional line. But he said he had not seen such a standard.

The challengers in the new case, Gill v. Whitford, No. 16-1161, say they have found a way to separate partisanship from the many other factors that influence how districts are drawn.

The case arrives at the court in the wake of Republican victories in state legislatures that allowed lawmakers to draw election maps favoring their party.

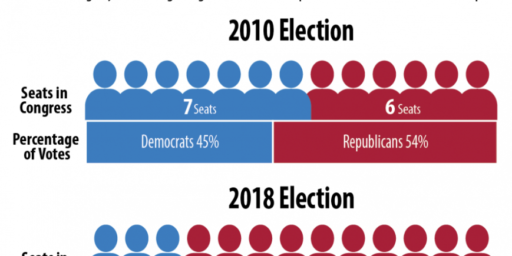

The case started when Republicans gained complete control of Wisconsin’s government in 2010 for the first time in more than 40 years. It was a redistricting year, and lawmakers promptly drew a map for the State Assembly that helped Republicans convert very close statewide vote totals into lopsided legislative majorities.

In 2012, Republicans won 48.6 percent of the statewide vote for Assembly candidates but captured 60 of the Assembly’s 99 seats. In 2014, 52 percent of the vote yielded 63 seats.

Last year, a divided three-judge Federal District Court panel ruled that Republicans had gone too far. The map, Judge Kenneth F. Ripple wrote for the majority, “was designed to make it more difficult for Democrats, compared to Republicans, to translate their votes into seats.”

The decision was the first from a federal court in more than 30 years to reject a voting map as partisan gerrymandering.

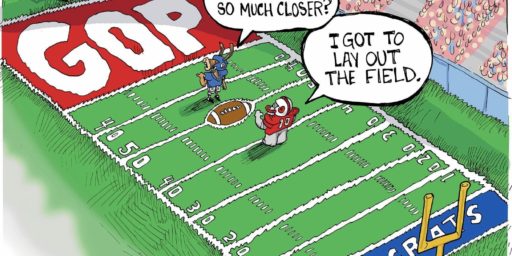

The new standard proposed by the challengers tries to measure the level of partisanship in legislative maps by counting “wasted votes” that result from the two basic ways of injecting partisan politics into drawing the maps: packing and cracking.

Packing many Democrats into a single district, for instance, wastes every Democratic vote beyond the bare majority needed to elect a Democratic candidate. Cracking, or spreading, Democratic voters across districts in which Republicans have small majorities wastes all of the Democratic votes when the Republican candidate wins.

In a 2015 article, Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos, a law professor at the University of Chicago and a lawyer for the plaintiffs, and Eric McGhee devised a formula to measure partisanship. The difference between the two parties’ wasted votes, divided by the total number of votes cast, yields an efficiency gap, they wrote.

Election law expert, and University of California law professor, Rick Hasen explains some of the legal background that has led us to this case:

For decades, voting-rights advocates who believe there is something unfair in letting partisan actors have free rein in drawing districts have looked to the courts to police to most egregious efforts to draw district lines to favor one party over another. Among other things, opponents of partisan gerrymandering have argued that allowing legislators to pick their voters rather than the other way around violates the Constitution’s equal-protection clause. The problem has been identifying when acceptable consideration of political party information to group similar voters together crosses the line into unconstitutionality.

In a 1986 case, Davis v. Bandemer, the Court announced that it could hear such cases (in technical legal terms, that the cases are “justiciable”), but it set forth a standard that was so hard to meet that there was never a successful claim. The Court reconsidered the issue in the 2004 case of Vieth v. Jubelirer. Four conservative justices, led by Justice Antonin Scalia, held that such claims were “nonjusticiable,” meaning that the Court could never hear such cases because there was no standard to separate permissible from impermissible consideration of party. The four liberal justices on the Court issued four separate opinions each setting forth a different standard which could be used to police the lines. Kennedy alone stood as the man in the middle, agreeing with the liberals that courts could hear these cases, but agreeing with the conservatives that each of the standards the liberals proposed, as well as a slightly different standard proposed by the plaintiffs in Vieth, were lacking. Kennedy suggested further consideration of the issue, looking perhaps at history, at analysis aided by technology, and at the First Amendment, which prevents certain government action that punishes people based on their partisan affiliation.

One way to understand the four different dissenting opinions in Vieth is that they were like contestants in a beauty pageant parading before Kennedy to see if there was anything he liked. And it has become clear that what’s happened since Viethin the lower courts has been more of the same: attempts in partisan gerrymandering cases to find a new “manageable” standard that would please Kennedy.

The lower court in the Gill case, which found last year that Wisconsin’s legislative districts were unconstitutional, relied partially upon the “efficiency gap,” a measure of partisan gerrymandering developed by Eric McGhee and Nicholas Stephanopoulos which focuses on how much a partisan redistricting plan “packs” and “cracks” the other party’s voters for partisan advantage.

According to the 2015 article discussed above, in a world where the districts are drawn in a perfectly nonpartisan manner, there would be no “efficiency gap.” The Plaintiffs in the Wisconsin case note that the gap was 12.2% in 2012 and 9.6% in 2014 according to the formula developed by Stephanoplous and McGhee and argue that gaps over 7% violate the Constitution. It was largely based on this argument that the lower court struck down the Wisconsin map and ordered the state legislature to redraw the district lines to reduce the partisan gap. The problem with the lower court’s ruling, of course, is the fact that the formula they rely on is based on presumptions that are not part of the Constitution and that there is no provision in the Constitution that even comes close to suggesting that there’s any functional or legal difference between a map with a 13.3% or 9.6% gap and one with a 7% gap. Additionally, the formula developed by Stephanopolous and McGhee is merely one of many meant to measure the alleged political partisanship of a particular redistricting map.

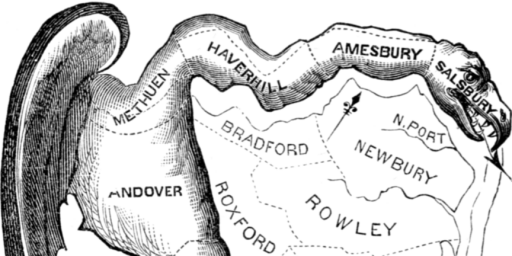

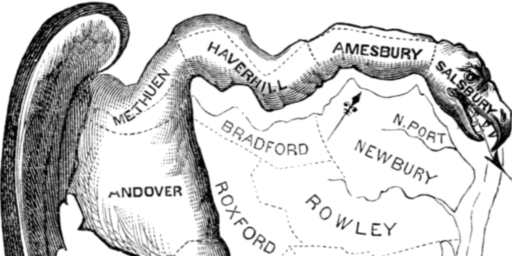

The biggest weakness in the Plaintiff’s case, though, seems to me to be the fact that there doesn’t seem to be any bar in the Constitution to a legislature controlled by one political party from creating district maps that favor its party to the detriment of others, nor does there appear to be any Federal law that bars the practice. In fact, the idea of partisan drafting of district lines is one that goes back to the very foundation of the republic, which is why it is named after Elbridge Gerry, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence who went on to be a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Congressman, Governor, and 5th Vice-President of the United States, serving under James Madison for a year until he died in 1814. Since then, political parties at the state level have regularly used the redistricting process to benefit themselves and, thanks to the fact that there are no real legal limitations upon them, Indeed, the Constitution seems to grant essentially unchecked authority to the states when it comes to redistricting. The only limitations that exist are those that prohibit the use of redistricting in manners tend to discriminate based on race. However, that argument was not made in the Wisconsin case and it does not appear that there is any case that the district lines in the state violate those restrictions. Given all of that, those looking to this case in the hope of a sweeping ruling against political gerrymandering shouldn’t start celebrating quite yet.

Clarence Thomas seems to understand when partisan gerrymandering is also effectively racial gerrymandering, if that case in NC is any indication.

In any case the fact that a minority party can pull shenanigans to get a majority or even a supermajority is obviously a flaw in the system. But our last two republican presidents lost the popular vote when they first got in, so it’s a flaw that definitely benefits one side.

Sadly, I think you’re right about the weakness of the plaintiff’s argument. It’s probably going to take a Constitutional amendment to fix this problem.

The other solution is for the democrats to adopt policies that actually appeal to people outside large cities.

But…nah.

I am a Wisconsin resident (and a fierce Independent/Libertarian-ish). There is absolutely no question that the GOP has turned a purple state into a deeply red partisan majority in the state Legislature. That is partly tied to geography with Madison and Milwaukee being where most of the Dems live. But, I do not know what sort of electoral wave the Democrats would have to achieve in order to flip either house of the state legislature. It may require as much as 60% of the statewide vote, and even that is probably not enough to overcome the advantage the GOP has in the lower house. Yeah, it’s that overwhelming for the GOP. Again, in as purple a state as there is.

I am no lawyer, and didn’t even get a law degree at Facebook (or Trump) University. Not taking into account any legal issues, this strikes me in practice as very similar to the whole definition of obscenity….”I can’t define it. But I know it when I see it.” It has absolutely systematically disenfranchised Democratic voters by ensuring that they stay in the minority and in some ways even disenfranchises moderate Republicans (We poor Independents/Libertarians are screwed no matter what).

All that said, don’t really expect much to come from this. I’d love to see it, but as you spell out…it’s not a legal slam dunk by any means. And, seems to be a legal long-shot.

I’m curious. Is there any rule that says a district has to be geographically contiguous?

@TM01: They already do, that’s why Republicans have to gerrymander to win elections. Pay attention.

@TM01:

I agree, a few hundred thousand people in Wyoming are more worthy of pandering to than a few million people in Los Angeles or New York City.

You can’t let this pass and still pretend you are a democracy.

Which means I fully expect the SC to uphold Wisconsin’s electoral map by a 5-4 vote along party lines.

I would love to be proven wrong, though.

@al-Alameda:

a month ago I drove from Seattle WA, through oregon, utah, wyoming, colorado, kansas, missouri, tennessee, kentucky, georgia and back into north florida.

I went from millions of people, to 3,000 miles of corn and the occasional hellishly stinky farm area, back to millions of people.

If i had my druthers I’d make the senate proportional. 40 million americans live in california with no more power in the senate than 750 thousand in South Dakota? That’s nuts.

That’s a bit misleading. While Elbridge Gerry was around at the time of the Constitution’s founding, the term “gerrymander” didn’t appear until 1812, and the word itself (a reference to a salamander, which the Congressional district in question was said to resemble) implicitly recognizes that it’s an abuse of the system. That doesn’t mean it’s unconstitutional, but it is most definitely a loophole that the Founders didn’t have in mind when they wrote the Constitution.

Kenneth Arrow

@Kylopod:

And yet, noting that many, if not most, of “the Founders” were still alive in 1812, Congress could have addressed, if not solved, that problem when they saw the injustice of it. Maybe it is a loophole that the founders had in mind when they wrote the Constitution and just didn’t care about. Or maybe they didn’t have it in mind but didn’t care when it presented itself, because “it’s just a one-time abnormality.” Hard to say.

We’ve had a

republicrelatively benign aristocracy for roughly 230 years. It’s up to us to keep it if we want it and cast it aside if we don’t. The fact that we’re coming into a period where the aristae are less benign means that we will have to be more careful about which ones we choose in the future. I don’t know how well we’ll pull that trick off given the fragmentation and foolishness of our times.@Just ‘nutha ig’nint cracker:

The reason it survived is the same reason the filibuster survived: both parties found it useful.

1-) The slaveholders that people call the “Founders” would never envision districts with one million voters, they wanted a Amendment with maximum population for each district. That makes gerrymandering more problematic, far more than under Gerry.

2-) People all over the world envy the way that American Congressmen works for and represent their constituents. Brazilian media noted that US Representative Chris Smith went to Rio with David Goldman to rescue his son.

Gerrymandering can destroy this precious relation, one of the best things in American Democracy.

So why is a guaranteed Black district ok? Why do the Democrats get guaranteed districts?

Tim Scott proves that a black person can win a statewide office, even in the south.

And where’s my Polish representative?

Right now, all I really see is more crybabies complaining that they keep losing so want a rule change….in their favor only.

Hell, let’s just make EVERY office a statewide office! Or just make every office based on national popular vote!