Supreme Court Hears Argument In Case Challenging Texas Redistricting

The Supreme Court heard oral argument yesterday in a case alleging that Texas's Congressional and state legislative districts were drawn with the intent to discriminate based on race.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court heard argument in a case arguing that the Congressional and state legislative district maps in Texas discriminate against minorities:

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court heard arguments on Tuesday in a long-running dispute over congressional and state legislative districts in Texas that challengers said discriminate against minority voters.

The case was the court’s third voting-rights case of the term. The two earlier ones, from Wisconsin and Maryland, concerned claims of partisan gerrymandering, where the political party in power draws maps to give its candidates an advantage. The Supreme Court has never struck down a voting district as a partisan gerrymander.

Tuesday’s argument concerned a more established legal theory, with the challengers arguing that Texas lawmakers had violated the Constitution and the Voting Rights Act by making it harder for minority voters to elect their preferred candidates.

Much of the argument concerned the issue of whether the case was properly before the justices at all.

Last year, a three-judge panel of the Federal District Court for the Western District of Texas, in San Antonio, ruled that a congressional district including Corpus Christi denied Hispanic voters “their opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice.” The district court also rejected a second congressional district stretching from San Antonio to Austin, saying that race had been the primary factor in drawing it.

In a separate decision, the district court found similar flaws in several state legislative districts.

But the court did not issue an injunction compelling the state to do anything, and only instructed Texas officials to promptly advise it about whether they would try to draw new maps.

“What does the piece of paper say here?” Justice Stephen G. Breyer asked. “It seems to me the piece of paper says come to court. Now, if we’re going to call that a grant of an injunction, we’re going to hear 50,000 appeals.”

There was a second curious wrinkle: The district court itself had, for the most part, endorsed the maps in 2012, after the Supreme Court rejected earlier ones and told the court to try again. The 2012 maps, the panel later said, had been considered in haste in advance of pending elections.

On Tuesday, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. at one point seemed to agree. “It was preliminary, as opposed to permanent,” he said of the court-drawn maps.

In 2013, the Texas Legislature decided not to draw new maps and instead mostly adopted the one drawn by the court in San Antonio. Scott A. Keller, Texas’ solicitor general, said state lawmakers had adopted the maps after substantial debate and deliberation.

“There is absolutely no evidence in plaintiffs’ briefs that somehow the Legislature was trying to lock in discriminatory districts,” he said.

Allison J. Riggs, a lawyer for the challengers, disagreed. The question for the justices, she said, was, “Did the Legislature adopt the interim plan for race-neutral reasons, or did it use the adoption of that interim plan as a mask for the discriminatory intent that had manifested itself just two years ago?”

Later in the argument, she answered her own question. “They wanted to end the litigation,” she said, “by maintaining the discrimination against black and Latino voters, muffling their growing political voice in a state where black and Latino voters’ population is exploding.”

After three election cycles that used the interim maps it had drawn, the district court ruled that they were flawed. “Although this court had ‘approved’ the maps for use as interim maps, given the severe time constraints it was operating under at the time of their adoption,” the court said that approval was “not based on a full examination of the record or the governing law” and was “subject to revision.”

The court concluded that Texas’ adoption of the interim maps was part of “a litigation strategy designed to insulate the 2011 or 2013 plans from further challenge, regardless of their legal infirmities.”

Edwin S. Kneedler, a lawyer for the federal government arguing in support of Texas, said it was a mistake to apply the flaws in the earlier map to the later one.

“The legal principle that went wrong,” he said, was that “the court basically said that the taint that it found with respect to certain districts in 2011 carried forward to 2013.”

Mr. Kneedler said the state deserved credit for trying to end the redistricting litigation by adopting the court-drawn map. “That’s something to be commended, when a state legislature proceeds in that manner,” he said.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor appeared unconvinced. “Are you ending a litigation,” she asked, “or are you ending the possibility of a court stopping you from discriminating?”

Amy Howe analyzes the argument at SCOTUSblog:

At the Supreme Court today, Texas solicitor general Scott Keller argued that the state legislature could not have been intentionally discriminating against minority voters when it adopted the maps that the district court itself had ordered the state to use. But Keller was quickly derailed by a topic that wound up occupying far more of the oral argument time than many would have expected: whether the Supreme Court has the authority to hear the case at all, when federal law only gives the court the power to hear appeals from a three-judge district court that either grants or denies an injunction.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor was the first to broach the topic, telling Keller that the state cannot appeal unless the district court “had made clear that it was issuing an injunction or prohibited you from using your map.”

Keller responded that, shortly after the district court ruled that the 2013 plans violated the Constitution and the Voting Rights Act, it “was ordering the state to appear for expedited court-drawn redistricting” – which had the same practical effect as an injunction.

But Justice Stephen Breyer was skeptical. He told Keller that when he became a judge in 1981, he was instructed that appeals had to come from either a judgment or the denial of an injunction. “You weren’t ordered,” he emphasized to Keller, because the district court issued “a piece of paper” that says “come to court” with a plan. If we allow this appeal to go forward, Breyer worried aloud, the Supreme Court will be faced with tens of thousands of appeals.

Justice Elena Kagan voiced similar concerns. If you are right, she told Keller, the Supreme Court will have to hear appeals in redistricting cases immediately after the three-judge district court finds that a map (or portions of a map) violates the Constitution or the Voting Rights Act, instead of waiting until the district court has come up with a remedy for the violations.

Keller pushed back, arguing that the state would be held in contempt if it told the district court that it would not appear in a few days to draw new maps. That answer prompted Justice Samuel Alito to ask what appeared to be a friendlier question: What would happen if the state told the district court that it intended to go ahead and hold elections under the old maps? The state would be held in contempt, Keller Arguing on behalf of the United States in support of Texas, U.S. Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler emphasized that the Texas legislature adopted the 2013 plan because it wanted to end the ongoing litigation and move on. That intent, he posited, is something to “be encouraged.”responded.

Justice Anthony Kennedy then joined the fray, although it is not clear which way his question (or Keller’s answer) cut. What if, Kennedy asked, the district court had given the state a 45-day window to appear to draw new maps, rather than a 3-day one? Would that order have the “practical effect” of an injunction?

Keller told Kennedy that it would still have the effect of an injunction, in part because Texas has a part-time legislature that was out of session when the district court issued its order. And in any event, he stressed, here the governor needed to call a special session within three days, which is “certainly not a reasonable opportunity for the legislature to” work to fix the problems with the maps.

When Keller eventually turned to the merits of the lower court’s ruling, he again emphasized the district court’s analysis in adopting the 2012 plan and the extensive “deliberative process” undertaken by the Texas legislature in 2013 when it adopted the existing plan. Both of those, he suggested, were “very good evidence” that the Texas legislature was operating in good faith when it enacted the 2013 plan.

(…)

Arguing on behalf of the United States in support of Texas, U.S. Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler emphasized that the Texas legislature adopted the 2013 plan because it wanted to end the ongoing litigation and move on. That intent, he posited, is something to “be encouraged.”

That argument may have gained some traction with Roberts, who told lawyer Max Hicks (who argued on behalf of the challengers to the congressional redistricting plan) that “it seems a strong argument” for the legislature to adopt the district court’s plan “to move things along.” Shouldn’t there be a presumption of good faith going forward, Roberts asked, “which is significant on the determination of their intent to discriminate?”

During his time at the lectern, Hicks tried to emphasize that things had changed between 2011 and 2013. The most important factor before the Texas legislature in 2013, he stressed, was one that hadn’t existed in 2011: Elections had been held using the existing maps, and so when the Texas legislature in 2013 decided to adopt the existing maps, it knew that it had accomplished what it had intended to do – the “tamping down” of minority voters. “Insanity,” Hicks told the justices, “is doing something over and over again and expecting different results.” In contrast, he concluded, “discrimination is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting and achieving the same results” – just what the Texas legislature accomplished by enacting its earlier maps.

Arguing on behalf of the statehouse plans, attorney Allison Riggs also tried to convince the justices that the Texas legislature had enacted the 2013 plan to “perpetuate its ill-gotten and racially discriminatory 2011 gains.” But Riggs, like Hicks, ran into questions from Roberts, who hypothesized that the Texas attorney general or legislature would use the district court’s interim plan if it wanted to “take your best shot at a plan that will be accepted by the district court.”

As I’ve said in the past, trying to reach conclusions about how a case might turn out based on oral argument is often an exercise in futility. Sometimes, the Justices have ulterior motives in asking particular questions of particular attorneys that aren’t necessarily connected to how they might ultimately rule in the case. That being said, it seems rather obvious that this is another one of those cases that is going to split the Court right down the middle between the liberal and conservative blocs and that the deciding vote in the case, once again, will likely come from Justice Kennedy. In that regard, the questioning from yesterday doesn’t appear to have provided any clues about which way the Court’s “decider in chief” may come down when the Justices meet to consider the case on Friday, or during the back and forth that may occur as the opinion is drafted between now and the end of the Court’s term in June. It’s worth noting, though, that in the past Justice Kennedy has wavered back and forth on Voting Rights Act cases such as this, so it’s hard to tell where he might come down on this case.

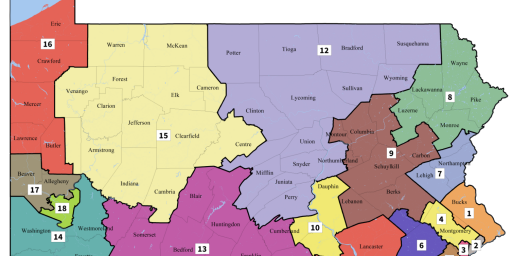

As far as the merits of the case are concerned, the Plaintiffs are contending that the Texas legislature acted with the intent to discriminate based on race when it drew the district maps that currently exist in the Lone Star State. The Plaintiffs are also alleging that the legislature acted with the intention of diluting the voting power of minority voters by creating districts that consisted of a majority of minority residents, thus creating a number of districts where minority voting power was minimized in a manner that violated the Voting Rights Act. This is specifically alleged with regard to the creation of the state’s 27th Congressional District and its 35th Congressional District. The 27th District is currently vacant but was previously represented by former Republican Congressman Blake Farenthold, who resigned due to allegations of sexual impropriety earlier this year. The 35th District, meanwhile, is a newly created district that is presently represented by Democratic Congressman Lloyd Doggett. The 37th District Has been criticized as one of the most extreme examples of Gerrymandering in the United States. If the Court decides for the Plaintiffs, it could mean that the Texas legislature would be required to redraw all of the districts for the state, although it’s likely that this would not impact the 2018 election since there will be at best a limited amount of time for this to be done before the midterm elections. Thus, the immediate impact of the ruling wouldn’t be felt until the 2020 election, and at that point, the maps will have to be redrawn yet again in the wake of the 2020 Census.

The interesting thing, of course, is that this case comes in the same term that the Court has also heard oral argument in two other cases involving redistricting and gerrymandering. Those cases, out of Wisconsin and Maryland, involved the different, although somewhat related, issue of politically-based Gerrymandering. While the issues involved in those cases, as well as similar cases arising out of North Carolina and Pennsylvania, are different than the issues presented by this case, the Court appeared to be as divided at the conclusion of those cases as it did after yesterday’s oral argument. As a result, it’s hard to predict exactly how the Court will come down on this issue, although it’s worth noting that the Voting Rights Act has not exactly fared well, a fact perhaps best noted by the Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder in which the Court ruled that Section 4(b) of the act was unconstitutional because its list of suspect states and districts was based on data that was more than forty years old. Justice Kennedy was part of the five-Justice majority in that case, so that does not bode well for the Plaintiff’s chances of success in the instant case.

As with the other gerrymandering cases, it’s unlikely that we’ll see a decision in this case until the end of the term. Until then, you can read up on the case if you wish by means of the documents filed at the SCOTUSBlog information page for the case.

Here’s the transcript of yesterday’s argument:

Abbott Et Al v. Perez Et Al by Doug Mataconis on Scribd