Supreme Court Clerks and Undergraduate Elitism

Culling for the primary feeder job in American legal system begins in high school.

NYT Supreme Court reporter Adam Liptak, a Yale and Yale Law graduate, worries that “The Road to a Supreme Court Clerkship Starts at Three Ivy League Colleges.”

When Ted Cruz attended Harvard Law School, he liked to study with people who had undergraduate degrees from Harvard, Yale or Princeton. “He said he didn’t want anybody from ‘minor Ivies’ like Penn or Brown,” one of his law school roommates told GQ.

That may strike you as slicing the baloney of elitism awfully thin. But a new study has found that Supreme Court justices do much the same thing in selecting their law clerks.

It is not news that the justices favor a handful of law schools in doling out clerkships, a glittering credential that all but guarantees success in a profession obsessed with status markers. But the study adds another factor: To get a clerkship, it really helps to have gone to college at Harvard, Yale or Princeton.

I am shocked—shocked!—that going to one of the three most prestigious universities in the country gives you a leg up on getting one of the most prestigious entry-level jobs in the country.

Albert Yoon, a law professor at the University of Toronto and one of the study’s authors, said the finding was disturbing.

“We don’t really live in a meritocracy,” he said. “The Supreme Court is guilty of perpetuating some of the worst pathologies in American society.”

As someone with three degrees from decidedly non-elite institutions, I need very little persuasion that there are talented folks who didn’t go to an elite university. I guarantee you that there’s a kid walking around the University of Mississippi—or even Boise State—campus today with the smarts to be a Supreme Court clerk given the right chances.

At the same time, it’s really, really hard to get into Harvard, Yale, or Princeton unless your daddy gave them a lot of money or is a Senator or something. So, let’s not pretend that graduating from one of those institutions isn’t a strong signal of merit, at least to the extent we want to call being born very smart and driven “merit.”

Each justice typically hires four law clerks per term. The study, which collected data on the 1,426 former clerks in the 40-year period ending in 2020, found that more than two-thirds of them attended just five law schools: Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Columbia and the University of Chicago. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., for instance, chose 58 clerks in the period covered by the study, 37 of them from Harvard or Yale.

Were I to hazard a guess, NYU would lead the pack among the other third. Why? Because they’re the only T-6 school not already on the list. And I’ll go out on a limb and say most of the rest are from the T-14 schools. Indeed, checking the paper itself, I see “The Top 14 schools together account for 86 percent of clerks (p.11).”

That’s less than I would have predicted, to be honest. Indeed, without doing a deep dive into the data, I would conjecture that those 14 percent are disproportionately from earlier in the dataset, which reaches back to 1980, before the T-14 concept was so strongly embedded in the legal culture by the US News and other ranking systems. (There’s also the fact that Justice Clarence Thomas, despite a Yale Law degree, deliberately tries to hire some clerks without an Ivy League pedigree.)

You might think that doing well at one of those law schools and then obtaining a prestigious clerkship with a federal appeals court judge would check the necessary boxes. But it turns out that undergraduate degrees seem to matter, too. Going to college at Harvard, Yale or Princeton — even after controlling for law school grades — gave applicants a significant boost, the study found.

Presuming they’ve also controlled for feeder judge (i.e., the record of success a given Appeals judge has of getting their clerks hired on as SCOTUS clerks), we now have something interesting. That should have folks past the point where undergraduate degree is a significant discriminator.

Mr. Cruz, now a senator from Texas, may be a case in point. He graduated with honors from Harvard Law School and served as a law clerk to Judge J. Michael Luttig before going on to clerk for Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist. And Mr. Cruz went to college at Princeton.

This, on the other hand, adds nothing to the conversation. Cruz, loathsome though he has demonstrated himself to be, is a brilliant legal mind who had checked all the right boxes in clerking for Luttig and has since demonstrated sufficient political skills to get elected to the Senate multiple times. It’s not shocking that he impressed Rehnquist—a Stanford man—with or without a Princeton BA.

The study, conducted by Professor Yoon, Tracey E. George of Vanderbilt University and Mitu Gulati of the University of Virginia, focused on Harvard Law School. It has long produced the most Supreme Court law clerks, partly because of its prestige and partly because it is much larger than some of its rivals. (A larger proportion of Yale Law School graduates have served as Supreme Court clerks.)

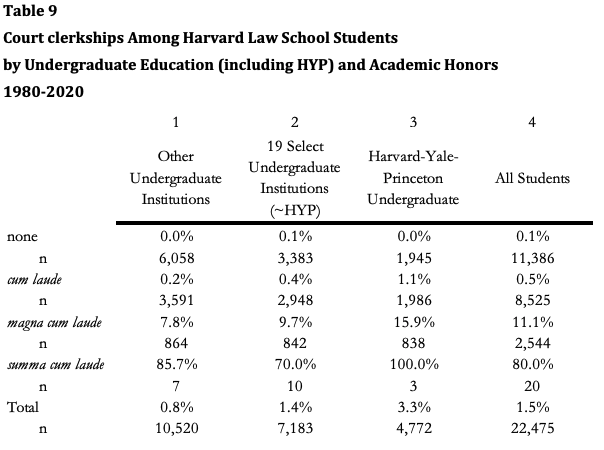

The study, which considered 22,475 Harvard Law graduates, took account of three data points: where they went to college, whether they qualified for academic honors in law school (graduating cum laude, magna cum laude or summa cum laude) and whether they obtained a Supreme Court clerkship.

About half of the graduates had attended one of 22 selective undergraduate institutions, and more than a fifth of the graduates had gone to college at Harvard, Yale or Princeton. Both of those groups graduated with honors from Harvard Law at above-average rates.

But here is the key point: Even controlling for achievement in law school as measured by academic honors, members of the two groups were more likely than their peers to obtain Supreme Court clerkships. And most of the difference could be traced to students who had gone to college at Harvard, Yale or Princeton.

They were three times as likely to get clerkships as those who had gone to the other 19 undergraduate institutions when graduating with cum laude honors and 50 percent more likely when graduating with magna cum laude honors. Both differences were statistically significant. (Summa cum laude honors were very rare and very often led to clerkships regardless of undergraduate institution.)

We learn on pp. 18-19 of that paper that “the Court’s clerkship selection process is a discreet, opaque process. There is no public record of who applies, who is granted interviews, and the offers they receive (there is a norm, however, that applicants accept their first offer from a justice). Thus, while we observe the universe of successful applicants to the Court, we do not observe unsuccessful applicants.”

So, they do a deep dive on Harvard Law students who graduated between 1980 and 2020—33% of whom had Ivy League degrees and 21% just from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. They do several breakdowns, of which I found this the most interesting:

The authors observe “the difference in Court clerkship rates between the 19 schools and

other (non-HYP) institutions are relatively small and statistically not significant. This breakdown suggests that HYP drives much of the effect of undergraduate institution on Court clerkships.” That seems a reasonable surmise.The bottom line, Professor George said, is that the road to a Supreme Court clerkship starts in college.

“Elite law school degrees don’t repair or overcome a lower-status undergraduate degree,” she said. “You can’t scrub your undergraduate degree with a law degree.”

Professor Gulati said there is something disturbing about this given that Supreme Court clerkships are government jobs, and clerical ones at that.

“The process seems highly biased toward elite private schools,” he said.

The problem, Professor Yoon said, was not with the young lawyers who made the cut. “The people who get Supreme Court clerkships are great,” he said. “But there are a lot of great people who don’t get it.”

Given that there are only 36 openings a year and literally a thousand times as many new law grads produced each year, it’s essentially guaranteed. I can’t imagine a selection process—even one that was incredibly more expensive and time-consuming—that wouldn’t leave out “a lot of great people.”

The justices themselves are products of elite educations. Eight of them attended law school at Harvard or Yale, and six of them have undergraduate degrees from Harvard, Yale or Princeton. And six of them had themselves served as law clerks at the Supreme Court.

There can be a clubby quality to the justices’ remarks about the schools they attended. Chief Justice Roberts, who has two Harvard degrees, was asked in 2009 whether Supreme Court justices “could relate to ordinary folks.”

The chief justice said he wanted to dispel a myth. “Not all justices went to elite institutions,” he said. “Some of them went to Yale.”

Ha!

Honestly, the most surprising thing I learned from scanning the paper wasn’t mentioned by Liptak at all.

A key feature of what we saw in the prior section was the importance of obtaining a

high-status appellate clerkship (with one of the small number of “feeder” judges) to get a

Court clerkship. Our understanding of the hiring process – with the caveat that this is another

aspect of this market that we lack systematic information on – is that the justices often make

their hiring decisions before the applicant has worked for the feeder judge at the lower court.

In that context, where the justice has no information about how the applicant performed

with the feeder, it strikes us as a bit strange that obtaining a clerkship with a feeder versus a

non-feeder judge should matter. After all, assuming that the Supreme Court Justice is making

their hiring decision a year after the student has obtained a clerkship with the feeder judge,

the Supreme Court Justice making their hiring decision has all the same information that that

lower court judge would have had, plus information from an additional year of grades and

references in law school. So, what is the information about having received a position with a

feeder judge adding to the equation such that it makes the candidate more attractive?

That’s weird, indeed. While it makes sense that the SCOTUS process would overlap such that a potential clerk wouldn’t have finished their Appeals clerkship, it never occurred to me that the section would take place before they even started. Then again, as the authors note near the outset of the paper, it has become increasingly common for SCOTUS clerks to have previously served twice as lower court clerks. (Indeed, at least early in her tenure on the court, Justice Elena Kagan tended to hire people who had already clerked for other Supreme Court Justices!) But, yes, it appears that this is mostly a function of having ideological kin do the sorting for the Justices.

As to the primary issue of the influence of undergraduate prestige on one’s career, it’s certainly exacerbated in legal circles because of how influential getting into a T-3/T-6/T-14 law school—and the competition to get a federal clerkship in order to compete for a Supreme Court clerkship—is. But, if not getting into Harvard, Yale, or Princeton at 17 or 18 essentially puts you behind the curve for the rest of your career, that’s rather harsh. Why, I imagine there are rich, talented, folks who think Stanford and Berkely are fine schools. The fools!

Then again, it’s not unique to the law. With the exception of the Marine Corps, for a variety of idiosyncratic reasons, graduating from a service academy is far and away the primary feeder to general/flag officer rank in the U.S. military. It can be overcome—why, the current Chairman of the Joint Chiefs went to Princeton!—academy grads make it to the highest levels at rates far, far disproportionate to their share of officer accessions.

Is this a typo? Because if it isn’t you seem to be arguing against yourself. Basically, it doesn’t seem like having a rich daddy or politically connected parents is demonstrative of intelligence or drive.

Since she’s not one of the ‘tribe’, it’d be [mildly] interesting to see if Justice Covid-Barrett perpetuates this kind of pre-sorting, or takes on clerks who are non-Ivies….

Does anyone have an example of Ted Cruz’s brilliant legal mind?

In order to get into an Ivy League school, one has had to make all the right decisions from a very early age.

It’s stupid (from an efficiency perspective) to assume that these are necessarily the best candidates. It is more indicative of ambition at a young age (or usually the parents’ ambition) than aptitude.

What does it say about an institution if it only hires people who were extremely ambitious at 14? Nothing good, I suspect.

Relatedly, while I don’t know about Yale or Princeton, the quality of the education to be had at Harvard isn’t necessarily great. Their faculty consists of a small number of highly paid “superstar” professors, but a lot (perhaps most) of the actual teaching is done by disposable non-tenure track staff – some of which (I can personally attest) are halfwits at best.

So no, SCOTUS definitely doesn’t hire the most qualified candidates.

If the researchers had carried their investigation down another level, we’d likely find that getting a SC clerkship in part depends on what elite prep school one attended.

MAGA Extremists – salt of the earth populists.

What jumps out at me is that the path to Harvard and Yale starts in middle school at the latest, and students that remain on that track are separated at an early age from the rest of the pack. As they progress they are increasingly isolated with people that have the same life experiences and motivations. A privileged d-bag like Brett Kavanaugh is an obvious example, but I bet Jackson’s post pubescent life experience is closer to his than to 99.9% of the country. Quite frankly, these people haven’t lived in the unprivileged world since they were in their early teens at the latest.

@Stormy Dragon: A friend of mine was in his law class at Harvard. She said he is very smart, and an insufferable snob.

@OzarkHillbilly: I’m partly joking but it’s simultaneously true that 1) Harvard, Yale, and Princeton are extraordinarily selective and that getting in is an indication of merit in most cases and that 2) there are a relatively small number of backdoor slots for the Jared Kushners of the world. (Also, while they strenuously deny it, if you’re a superstar athlete in a sport they care about.)

@Stormy Dragon: Cruz had immigrant parents with no money or social clout, went to nothing religious schools, and blazed an impressive path from there:

He went on the get the most prestigious clerkships possible, Luttig and then the Chief Justice, and the rest is history. Those are extraordinary achievements. It’s just silly to argue otherwise.

@drj: It really depends on what you mean by “best-qualified.” I have come to think that we’d be better off with more well-rounded candidates in terms of life experiences. (I ultimately recanted my arguments against Harriet Miers, for example.) But it has long been established that SCOTUS clerkships are designed to identify the folks most likely to be brilliant legal scholars and, indeed, to become future federal judges, including future SCOTUS justices. They’ve been remarkably successful in that regard, albeit granted that there’s a self-fulfilling prophecy to all that.

@MarkedMan:

What jumps out at me is that the path to Harvard and Yale starts in middle school at the latest,

I know at least four people who have attended Harvard: three for undergrad, one for law school. Not one of them had their sights set on Harvard from middle school. It was more the reverse–they had the grades, so Harvard was a viable option. My best friend’s daughter picked Harvard for her undergrad because with all of the assistance she received, it ended up being less expensive than her in-state university (University of Illinois). The friend who was in law school with Cruz is a friend of mine from college–I attended a small, private liberal arts school in Ohio.

Obviously, anecdotes are not data, but the only four people I know who actually attended Harvard don’t conform to the “on that path since middle school” pattern.

@Jen: This may be true to some extent for the general student body at Harvard, and I know a number of people myself who fall into the category you mentioned. But here we are talking about people destined for Supreme Court clerkships. And, semi-anecdotally, when we lived in Connecticut we socialized with an admissions officer for Yale (just friends, nothing to do with Yale) and the stories she would tell would curdle your blood. There are professional coaches to get you into those programs and they start at very early ages.

@James Joyner:

Could you give an example of a piece of brilliant legal writing or analysis?

You do get that legal thought isn’t something that can be objectively right, don’t you?

There simply isn’t something like “true law” waiting to be discovered by only the most brilliant of lawyers.

This is not to say that clerking doesn’t require

significant intellectual rigor, But that mostly involves dotting your i’s and crossing your t’s (mostly to avoid unintended consequences). Where is the brilliancy?

@James Joyner:

I didn’t ask for evidence he’s an achiever, I asked for evidence he had a brilliant legal mind. I wrote a thesis too, but I wouldn’t describe myself as having “a brilliant computer science mind”.

And frankly, I consider winning debate awards as evidence AGAINST having a brilliant legal mind. I’ll concede, however, that Cruz is a brilliant talker.

@Stormy Dragon: I have no doubt Cruz is a “brilliant legal mind”, although I’m not sure that’s entirely a compliment. The problem is that he’s also an exceptional raging asshole. I wonder if, in general, the correlation between those two characteristics isn’t positive.

@James Joyner: writes that most people get into Harvard/Yale on merit and there’s a back door for the merely wealthy like Kushner. I don’t care enough to dig it out, but I seem to recall reading elsewhere the majority of students are legacy, donor, athlete, and the backdoor is for the merely talented.

And the Federalist Society is hovering ominously somewhere in the background of all this.

@gVOR08: It turns out that a Judge made Harvard release it’s legacy rate for the Class of 2022. For this purpose “legacy” is defined as being a direct descendant of someone who attended Harvard, i.e. Aunt or Uncle doesn’t count. Here’s what they submitted:

Another fascinating tidbit is that when Class of 2024 Harvard freshman were asked if they were legacy, only 12% said yes. Did Harvard really reduce their legacy admission rate by two thirds in just two years? I doubt it. Such a move would create an incredible backlash and that would have made the news.

@MarkedMan: I’m trying to remember where I came across it, but I remember reading that legacies are FAR more likely to become alumni donors than any other group, including “original” graduates. So, there’s a huge financial incentive for higher ed institutions to admit legacies (and, if I’m remembering correctly this holds true of non-Ivies as well–your best donors are legacy graduates).

@Jen: You show up at an Ivy at 18 years old and the environment is so much different than almost any other college. Things are prepared for you, you are advised and counseled and cossetted. Sign up systems work, or if they don’t, you can demand that they do and someone will make sure you get into your classes. I have a relative who went to McGill in Montreal (Unofficial Motto: “Harvard, the McGill of the South”) and the experience was very different from his sister, who went to a “Name” Boston school (not an Ivy). McGill costs much less than US schools and, while they have more counseling and support staff than my school had back in the day, they don’t have anywhere near as much as in the US, so students are on their own much more. I mean, Harvard has a 98% graduation rate and, yes, I get that Harvard students are highly motivated, but even that student body wouldn’t get to 98% without a hell of a lot of hand holding. These judges, who have spent every minute of their adult life in such an environment, simple have no direct experience of regular life and the institutional injustices that can steamroller over the little guy.

@MarkedMan:

How dare you say this about the bestest and brightest and wisest and everything else-est the nation has to offer? If these people have no direct experience of regular life and institutional injustices, it’s simply because those concepts are part of the lying lies lying liberals tell to take deserved spots away from the meritocracy’s heirs and give them to commoners in a misguided attempt to tilt the advantage toward people who don’t deserve any advantage because they didn’t do anything to gain them some.

@MarkedMan: Okay…for the record, I was specifically and narrowly just responding to your post about legacy admissions. It’s an interesting sub-group to study. I’m fascinated by the idea that they are more likely to donate to colleges and universities than their parents, the OG graduates.