Supreme Court: Government Cannot Ban Violent Video Games For Children

The Supreme Court struck down a ban on the sale of violent video games to children, a victory for the First Amendment and parental authority.

In a highly anticipated opinion, the Supreme Court today struck down a California law that attempted to ban the sale or rental of “violent” video games to children:

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court on Monday struck down on First Amendment grounds a California law that barred the sale of violent video games to children. The 7-to-2 decision was the latest in a series of rulings protecting free speech, joining ones on funeral protests, videos showing cruelty to animals and political speech by corporations.

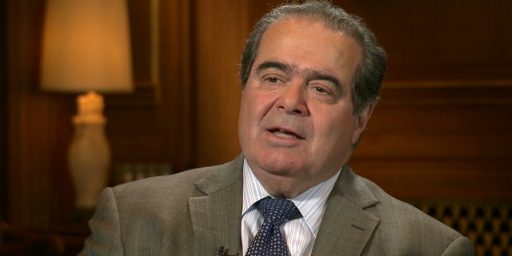

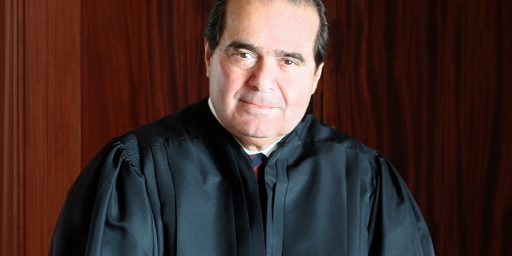

Justice Antonin Scalia., writing for five justices in the majority in the video games decision, Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, No. 08-1448, said the court refused to create a new category of speech beyond the protection of the First Amendment. Depictions of violence, he said, have never been subject to government regulation.

The fact that the law tried to protect children, Justice Scalia added, did not alter the analysis. Justices Anthony M. Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan joined the majority opinion.

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. voted with the majority but did not adopt its reasoning. His concurrence was joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. Justice Alito said the California law was too vague even though it was meant to address an authentic problem. A more carefully crafted law, he wrote, might survive constitutional scrutiny.

Justices Clarence Thomas and Stephen G. Breyer filed separate dissents. Justice Thomas said the Constitution did not protect minors’ free speech rights, while Justice Breyer said the statute survived First Amendment scrutiny.

The California law would have imposed $1,000 fines on stores that sold violent video games to people under 18. It defined violent games as those “in which the range of options available to a player includes killing, maiming, dismembering or sexually assaulting an image of a human being” in a way that was “patently offensive,” appeals to minors’ “deviant or morbid interests” and lacked “serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.”

The definitions tracked language from decisions upholding laws regulating sexual content. In 1968, in Ginsberg v. New York, the court allowed limits on the distribution to minors of sexual materials like what it called “girlie magazines” that fell well short of obscenity, which is unprotected by the First Amendment.

The video game industry, with annual sales of more than00 $10 billion, welcomed Monday’s ruling. The industry had viewed the court’s decision to hear the case as worrisome given that the lower courts had been in agreement that laws regulating violent expression were unconstitutional.

This is the third case in the last year and a half or so in which the Supreme Court has, by a wide margin, struck down content-based restrictions on speech. In the first case, United States v. Stevens, which was decided last term, the Court struck down a Federal law that banned the creation or sale of videos of animal cruelty. Using the Stevens decision as a starting point, Justice Scalia wrote for the majority that mere depictions of violence do not make speech entitled to less protection in the manner that, say, obscene depictions of sexual activity do:

As in Stevens, California has tried to make violent-speech regulation look like obscenity regulation by appending a saving clause re-quired for the latter. That does not suffice. Our cases have been clear that the obscenity exception to the FirstAmendment does not cover whatever a legislature finds shocking, but only depictions of “sexual conduct,” Miller, supra, at 24. See also Cohen v. California, 403 U. S. 15, 20 (1971); Roth, supra, at 487, and n. 20.

Stevens was not the first time we have encountered and rejected a State’s attempt to shoehorn speech about vio-lence into obscenity. In Winters, we considered a New York criminal statute “forbid[ding] the massing of stories of bloodshed and lust in such a way as to incite to crimeagainst the person,” 333 U. S., at 514. The New York Court of Appeals upheld the provision as a law against obscenity. “[T]here can be no more precise test of writtenindecency or obscenity,” it said, “than the continuing andchangeable experience of the community as to what typesof books are likely to bring about the corruption of publicmorals or other analogous injury to the public order.” Id., at 514 (internal quotation marks omitted). That is of course the same expansive view of governmental power to abridge the freedom of speech based on interest-balancing that we rejected in Stevens. Our opinion in Winters, which concluded that the New York statute failed a heightened vagueness standard applicable to restrictions upon speech entitled to First Amendment protection, 333 U. S., at 517-519, made clear that violence is not part of the obscenity that the Constitution permits to be regulated. The speech reached by the statute contained “no indecency or obscen-ity in any sense heretofore known to the law.” Id., at 519.

Because speech about violence is not obscene, it is of noconsequence that California’s statute mimics the New York statute regulating obscenity-for-minors that weupheld in Ginsberg v. New York, 390 U. S. 629 (1968).That case approved a prohibition on the sale to minors of sexual material that would be obscene from the perspec-tive of a child.2 We held that the legislature could”adjus[t] the definition of obscenity ‘to social realities by permitting the appeal of this type of material to be as-sessed in terms of the sexual interests . . .’ of . . . minors. ” Id., at 638 (quoting Mishkin v. New York, 383 U. S. 502, 509 (1966)). And because “obscenity is not protectedexpression,” the New York statute could be sustained so long as the legislature’s judgment that the proscribed materials were harmful to children “was not irrational.” 390 U. S., at 641.

Moreover, and perhaps most significantly, Scalia rejects the idea that the speech is subject to any different regulation with respect to minors:

“[M]inors are entitled to a significant measure of First Amendmentprotection, and only in relatively narrow and well-definedcircumstances may government bar public dissemination of protected materials to them.” Erznoznik v. Jacksonville, 422 U. S. 205, 212-213 (1975) (citation omitted). No doubt a State possesses legitimate power to protect chil-dren from harm, Ginsberg, supra, at 640-641; Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U. S. 158, 165 (1944), but that doesnot include a free-floating power to restrict the ideas to which children may be exposed. “Speech that is neither obscene as to youths nor subject to some other legitimate proscription cannot be suppressed solely to protect the young from ideas or images that a legislative body thinksunsuitable for them.” Erznoznik, supra, at 213-214.

Cleverly, I think, Scalia then goes on to point out that many of the books that have been long-standing children’s classics are, in fact, rather violent in their own way:

[T]he books we give children to read—orread to them when they are younger—contain no shortageof gore. Grimm’s Fairy Tales, for example, are grim in-deed. As her just deserts for trying to poison Snow White, the wicked queen is made to dance in red hot slippers “till she fell dead on the floor, a sad example of envy and jeal-ousy.” The Complete Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales 198 (2006 ed.). Cinderella’s evil stepsisters have their eyes pecked out by doves. Id., at 95. And Hansel and Gretel (children!) kill their captor by baking her in an oven. Id., at 54.

High-school reading lists are full of similar fare. Homer’s Odysseus blinds Polyphemus the Cyclops bygrinding out his eye with a heated stake. The Odyssey ofHomer, Book IX, p. 125 (S. Butcher & A. Lang transls.1909) (“Even so did we seize the fiery-pointed brand and whirled it round in his eye, and the blood flowed about the heated bar. And the breath of the flame singed his eyelids and brows all about, as the ball of the eye burnt away, and the roots thereof crackled in the flame”). In the Inferno, Dante and Virgil watch corrupt politicians struggle to stay submerged beneath a lake of boiling pitch, lest they beskewered by devils above the surface. Canto XXI, pp.187-189 (A. Mandelbaum transl. Bantam Classic ed.1982). And Golding’s Lord of the Flies recounts how a schoolboy called Piggy is savagely murdered by other children while marooned on an island. W. Golding, Lord of the Flies 208-209 (1997 ed.).

As Justice Scalia says in a footnote “Crudely violent video games, tawdry TV shows, and cheap novels and magazines are no less forms of speech than The Divine Comedy,and restrictions upon them must survive strict scrutiny.” And, under Scalia’s devastating analysis the California law really has no chance.

Justice Alito concurred in the result. but issued an opinion where he argued that the problem with the law was that it was unconstitutionally vague, and that a better drafted law should withstanding constitutional scrutiny. He was joined in that opinion by Chief Justice Roberts. In dissent, were Justice Breyer and Justice Thomas, who came at the issue from two very different directions.

Justice Breyer essentially argued that the law does in fact withstand First Amendment strict scrutiny:

California’s law imposes no more than a modest restriction on expression. The statute prevents no one from playing a video game, it prevents no adult from buying avideo game, and it prevents no child or adolescent from obtaining a game provided a parent is willing to help. §1746.1(c). All it prevents is a child or adolescent from buying, without a parent’s assistance, a gruesomely violent video game of a kind that the industry itself tells us it wants to keep out of the hands of those under the age of 17. See Brief for Respondents 8.

Nor is the statute, if upheld, likely to create a precedent that would adversely affect other media, say films, or videos, or books. A typical video game involves a significant amount of physical activity. See ante, at 13-14 (ALITO, J., concurring in judgment) (citing examples of the increasing interactivity of video game controllers). And pushing buttons that achieve an interactive, virtual form of target practice (using images of human beings as targets), while containing an expressive component, is not just like watching a typical movie.

Justice Thomas, on the other hand, argued that there was no First Amendment right applicable to speech directed at children:

As originally understood, the First Amendment’s protection against laws “abridging the freedom of speech” did not extend to all speech. “There are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem.” Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568, 571-572 (1942); see also United States v. Stevens, 559 U. S. ___, ___ (2010) (slip op., at 5-6). Laws regulating such speech do not “abridg[e] the freedom ofspeech” because such speech is understood to fall outside “the freedom of speech.” See Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coa-lition, 535 U. S. 234, 245-246 (2002).

In my view, the “practices and beliefs held by the Founders” reveal another category of excluded speech: speech to minor children bypassing their parents. McIntyre, supra, at 360. The historical evidence shows that the founding generation believed parents had absolute authority over their minor children and expected parents to use that authority to direct the proper development of their children. It would be absurd to suggest that such a society understood “the freedom of speech” to include a right tospeak to minors (or a corresponding right of minors toaccess speech) without going through the minors’ parents.Cf. Brief for Common Sense Media as Amicus Curiae 12-15. The founding generation would not have considered it an abridgment of “the freedom of speech” to supportparental authority by restricting speech that bypasses minors’ parents.

Of course, as Justice Scalia noted in the excerpt I quoted above, Thomas ignored the Court’s decision in Erznoznik v. Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205 (1975), which struck down a city ordinance that banned the showing of any film that depicted nudity at a drive-in theater and which was in part justified on the ground that it was meant to protect children. Given that decision, and others that Scalia cited, it’s clear that Thomas’s suggestion that a speaker loses his or her First Amendment rights when their expression is directed primarily, or even incidentally, at children is simply without merit.

The reactions to the decision are about what you’d expect. The video game industry is generally pleased. Which groups like The Parents Television Council, which supported the law, was entirely predictable:

Today, the Supreme Court upended a California law that would hold video game retailers accountable for selling or renting adult games to unaccompanied minor children. The Parents Television Council™ denounced today’s ruling in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, but pledged to continue holding irresponsible video game retailers publicly accountable.

“When an industry trade group files a federal lawsuit to defend a child’s constitutional rights, the alarm bells should be deafening. It is hard to imagine a more cynical proposition. Sadly, today’s ruling proves the United States Supreme Court heard the video game industry loud and clear, but turned a deaf ear to concerned parents. The Court has provided children with a Constitutionally-protected end-run on parental authority,” said PTC President Tim Winter.

“This ruling replaces the authority of parents with the economic interests of the video game industry. With no fear of any consequence for violating the video game industry’s own age restriction guidelines, retailers can now openly, brazenly sell games with unspeakable violence and adult content even to the youngest of children.

Nothing could be further from the truth, of course. There’s nothing in today’s opinion that prevents parents from regulating what video games their children are allowed to purchase or rent and, as Hot Air’s Ed Morrissey notes, it’s parental authority that’s really the preferable one here:

The restriction of such materials should be the decision of the parent and not the state. Parents can and do have a great deal of influence and power to affect a ban, if they see fit to do so. Wal-Mart and other retailers already have restrictions on what kind of entertainment they’re willing to sell at all (not just to children) thanks to the economic power of parents. The California law was an attempt to insert the police into what should have been a private parental decision, a further regulation on business that turned retailers into the equivalent of bar owners, and for little public-safety purpose

This was a victory not only for the First Amendment, but also for parental authority over the authority of the state. Isn’t that what a “pro-family”organization would want?

Here’s the Court’s opinion and accompanying concurrence and dissents:

As a gamer, I heartily approve of this ruling 🙂

A recent study suggested that violent games actually reduce violent crime:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1804959

I guess the fact that otherwise violent people are instead wasting their time playing video games outweighs the fact that video games increase aggressive behavior.

I’m reminded of the south park episode where the public is more willing to overlook children being subjected to violence while being outraged over children being subjected to sexual content.

Also I need a lawyer to explain the consistencies in constitutional law as it regards sales to children. Do we have age laws for the sales of firearms? Are these constitutional?

So children are prohibited from going to R rates movies but not from purchasing Grand Theft Auto. What’s the difference?

There’s no law actually enforcing the R-rated movie age limit. Theaters are free to let them in, but choose not to. Likewise, most video game stores require ID to purchase M-rated video games, even if there’s no legal requirement to do so.

@Laurie and @Stormy: I was going to raise the same point before getting waylaid into two meetings. But, if in fact “R” rated movie enforcement is merely at the discretion of theater operators with no legal sanction, that makes sense. Then again, don’t states have laws against selling pornos to kids?

@Stormy Dragon & @Laurie:

Interesting side note — the MPAA is an interesting example of shifting industry power when it comes to regulation. The rating system, and the motion picture code before it, were largely voluntarily instated to head off the specter of governmental regulation.

The evolution of the code (and its early enforcement) is a fascinating study (and violence has always been preferred to sex — though the violence was far more regulated in the 40’s and 50’s).

If the video game industry had come of age in that same time-frame, I expect we’d see a much higher degree of industry regulation. But having come of age in the 90’s and early 2000’s, we see something entirely different (and far less regulated).