The Eurozone Crisis Won’t Just Go Away

Despite what appear to be the fond hope of European central bankers that it will just all go away, something needs to be done. But what?

Martin Wolf summarizes the predicament in which the countries of the Eurozone find themselves:

Events have, in short, thoroughly falsified the premises of the original design. If that is the design the dominant members still want, they must remove some of the existing members. Managing that process is, however, nigh on impossible. If, however, they want the eurozone to work as it is, at least three changes are inescapable. First, banking systems cannot be allowed to remain national. Banks must be backed by a common treasury or by the treasury of unimpeachably solvent member states. Second, cross-border crisis finance must be shifted from the ESCB to a sufficiently large public fund. Third, if the perils of sovereign defaults are to be avoided, as the ECB insists, finance of weak countries must be taken out of the market for years, perhaps even a decade. Such finance must be offered on manageable conditions in terms of the cost but stiff requirements in terms of the reforms. Whether the resulting system should be called a “transfer union” is uncertain: that depends on whether borrowers pay everything back (which I doubt). But it would surely be a “support union”.

The eurozone confronts a choice between two intolerable options: either default and partial dissolution or open-ended official support. The existence of this choice proves that an enduring union will at the very least need deeper financial integration and greater fiscal support than was originally envisaged. How will the politics of these choices now play out? I truly have no idea. I wonder whether anybody does.

Several strategies for dealing with the crisis have been proposed:

- Remove the offending debtor nations from the Eurozone. This would enable them to establish their own currencies and manage their debt situation with a floating currency rather than being harnessed to the euro.

- Remove the creditor nations, particularly Germany, from the eurozone. This would enable the remaining participants in the euro to revalue the currency in such a way that it would, presumably, help the debtors deal with their fiscal problems.

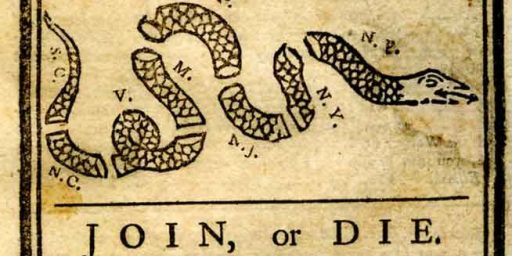

- Debt restructuring for the debtor countries. If, as has been suggested, the European Central Bank then refuses to lend against the debt of defaulting countries, the consequences could be quite severe for the lending banks, cf. the graphic above.

- In Felix Salmon’s words “Europe’s richest governments aiming a firehose of their taxpayers’ euros, in open-ended and unlimited quantities, at any country facing massive outflows.”

Given these choices, it’s easy to see how Europe’s politicians and central bankers are doing everything they can to kick the can down the road and put off the moment that they have to make a big decision. But the longer they wait, of course, the more momentous and more difficult any such decision is going to be. Just how much risk are Europe’s central banks going to take on, before they draw the line and say no mas?

Something that leapt out at me from the graphic above was Luxembourg’s enormous level of intra-eurosystem debt. That’s a multiple of Luxembourg’s total GDP! The implication is that although Germany is the largest creditor it might not be the creditor most affected by debt restructuring.

A peak of the iron first is starting to show under the velvet glove. Jean-Claude Trichet, current president of the ECB, in a speech on receiving the Charlemagne Prize made the following remarks:

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, we face the challenge of supporting countries that experience financial difficulties.

Arrangements are currently in place, involving financial assistance under strict conditions, fully in line with the IMF policy. I am aware that some observers have concerns about where this leads. The line between regional solidarity and individual responsibility could become blurred if the conditionality is not rigorously complied with.

In my view, it could be appropriate to foresee for the medium term two stages for countries in difficulty. This would naturally demand a change of the Treaty.

As a first stage, it is justified to provide financial assistance in the context of a strong adjustment programme. It is appropriate to give countries an opportunity to put the situation right themselves and to restore stability.

At the same time, such assistance is in the interests of the euro area as a whole, as it prevents crises spreading in a way that could cause harm to other countries.

It is of paramount importance that adjustment occurs; that countries – governments and opposition – unite behind the effort; and that contributing countries survey with great care the implementation of the programme.

But if a country is still not delivering, I think all would agree that the second stage has to be different.

Would it go too far if we envisaged, at this second stage, giving euro area authorities a much deeper and authoritative say in the formation of the country’s economic policies if these go harmfully astray? A direct influence, well over and above the reinforced surveillance that is presently envisaged?

But which countries are “not delivering”? If the answer is borrowing countries, doesn’t this take lending institutions, mostly in Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and so on, completely off the hook? Surely they must have known the economic and political conditions in the countries to which they were lending. Why absolve them from blame?

The crisis in the eurozone has not been induced by American policy—it is a crisis of the Europeans’ own making. There’s very little partisan advantage to be gained from it. Nonetheless, it is of significance here for a number of reasons.

First, the U. S. is a major participant in the IMF and the IMF is on the hook to the tune of tens of billions of dollars in bailouts. Second, the eurozone collectively is not only a major trading partner of ours but a major trading partner to our major trading partners. Sub par economic growth in Europe hurts economic growth here. An economically strong and vibrant Europe will help the U. S. economy, something we surely could use.

Third, NATO, the military alliance that the U. S. has with various European countries, is already participating in military action in a number of places, notably Afghanistan and Libya. Our European allies are already underfunding their militaries relative to the commitments they’ve made and economic woes will undoubtedly induce more pressure to decrease their military spending further.

For those of us watching the data, it isn’t too much of a news flash that things haven’t gotten better. We’ve been in a sideways drift for months now.

Heck, we even talked about “L shaped recoveries” a year ago.

So, is that “news” just that it is looking like that “L”, or is there really data for a further breakdown?

This McClatchy story is about the US, but I”m going to say it is the same vibe:

Bad economic news piles up, sending stocks down

You know what this looks like? It’s non-news to those of us who were pessimistic all the way through, but it’s a “turn” for those who weren’t. If you followed the optimism boom supported by mass media, then you can be surprised now.

A conspiracy theorist would put this down to Wall Street generating buys on the way up, and sells on the way down, but it’s probably just the freakishness of human crowd behavior.

Ideas move in packs.

I lived in Germany from 2000-03, just when the whole Euro thing became really big (I was there when they switched from the the DM to the Euro). One thing I particularly remember from the news at the time was that the Italian economy was a particular sticking point – The EU board basically decided to ignore its own published standards in order to let the Italians join. If they’d actually held their ground, Italy could never have come in, because there would never have been the sort of stability & guarantees within Italian economy. Apparently, those standards were just lip service for a lot of others, too.

When you say this is a crisis of the EU’s own making, you aren’t kidding…

Anyone who’s read “The Rotten Heart of Europe” could have predicted this.

I suspect that some combination of haircuts for bondholders, banks taking a bit of a hit and borrower countries paying back some of their debt is the only way to, maybe, keep things together. Austerity has rarely worked w/o the concurrent ability to devalue currency. Overall, I think Europe is worse off than we are. (My greek co-blogger informed me that Greece has been in some sort of default for 150 of the last 200 years. What does that say about banks that loaned to them?)

Steve

What does that say about banks that loaned to them?

The same thing it says about the banks that caused the financial crisis here in the US – that they knew no matter how the market went, they’d be covered, regardless of who else took a bath.

One of the most fundamental concepts in a free-market economy is entrepreneurial risk. But if the major investors aren’t actually taking any risks – playing fast & loose with other people’s money that will either be paid back by profits if they win or gov’t guarantees if they lose – then they’ve stopped being entrepreneurs and started becoming parasites.