The Filibuster Needs to Go

It is not a tool to foster compromise. It is tool of obstruction, plain and simple.

Speaking of reform, I would recommend doing away with the legislative filibuster. At the most fundamental level it would allow parties to show what they do, and do not, stand for in terms of legislation. That, in and of itself, would be an improvement over current conditions. It is also an essential first step towards any additional reforms, be they small or large.

Let’s start with a fundamental fact of the way representative democracy ought to work: if a party wins majority control of the legislature, it should be allowed to legislate. Voters should then be able to evaluate those policy outcomes and then be in a position to further endorse the party that passed those policies into law or to punish them at the ballot box.

This simple model does not work in the US as it should for a variety of reasons, but a major one is the simple fact that legislative minorities in the Senate have a veto on the legislative process.

And, it should be noted, that veto is not just a tool of the minority of the members in the chamber, but can be a veto by Senators who represent a substantial minority of the overall population.

As Philip Bump noted in a recent WaPo piece:

The Senate is already an institution that distributes power unevenly. States that make up only 16 percent of the country’s population cumulatively are represented by 50 senators, half of the total. Reduce the bar to 41 senators and you’re talking about just under 11 percent of the population. Meaning that senators representing a bit over one-10th of the country could block any legislation from passing.

To summarize, the filibuster is a mechanism that gives the minority party (that often represents a minority of the population) a veto over a large chunk of legislation (although there are some ways around it).

It is not a mechanism to build compromise.

It is not a mechanism to build bipartisanship.

It is not a romantic way for Jimmy Stewartesque Senators to fight for justice.

It is not even about actual debate (i.e., talking).

It is a procedural mechanism that allows 41% of the chamber to stop legislation.

As Jonathan Chait (All the Lies They Told Us About the Filibuster, which is worth reading in full) notes:

Filibuster advocates depicted it as a way of ensuring “unlimited debate,” akin to free speech. Except the filibuster’s most enthusiastic advocates preferred to smother legislation without any debate or vote at all, resorting to that tactic only if quieter methods had failed. In its modern method, it rarely involves any debate on the Senate floor at all. Filibusters prevent debates from taking place rather than allowing them. (Not that it matters — debates in the modern era are mere exchanges of talking points that have no bearing on the outcome of bills, which is negotiated off the floor.)

Nor do they force the Senate to reach consensus. As Jentleson shows, filibusters often kill moderate measures that command wide support among both parties. After the horrifying Newtown massacre, pro-gun Democrat Joe Manchin and Republican Pat Toomey negotiated a handful of concrete steps that had overwhelming public support (including among gun owners), such as background checks for purchasing firearms. The bill died of a Republican filibuster, the brief debate a mere afterthought.

By custom, filibusters in the 20th century were reserved for civil-rights laws. (This was in keeping with the broad unstated agreement among most white Americans to not let the oppression of Black Americans come between them as it had around the Civil War.) Only by the 1990s was it frequently used for non-civil-rights measures, and not until the Obama presidency did it harden into a routine supermajority requirement.

It is part of the broader problem of legislative weakness and flow of power to the executive and the courts because it disincentivizes legislation. If, for example, you don’t like the cascade of executive actions we see from presidents, the legislative filibuster is part of the problem.

When Senator McConnell makes claims such as the following via Axios (“You don’t destroy the Senate for fleeting advantage”), he is being self-servingly dishonest:

“If your legislation can’t pass the Senate, you don’t scrap the rules or lower the standards. You improve your idea, take your case to the people, or both,” McConnell said in a speech on the Senate floor.

[…]

“No short term policy win justifies destroying the Senate as we know it.”

This is dishonest because it perpetuates the myth that this is the way the Senate has always worked and that therefore destroying the filibuster destroys the Senate. While it is true that there have never been any limitations on debate in the Senate, the reality is clear: it has only become an essentially 60-vote body in recent years. It is really a phenomenon that is less than twenty years old.

It should be noted that McConnell was more than happy to take the 60-vote requirement away from SCOTUS nominations when it suited him. He is simply not an honest actor on this topic.

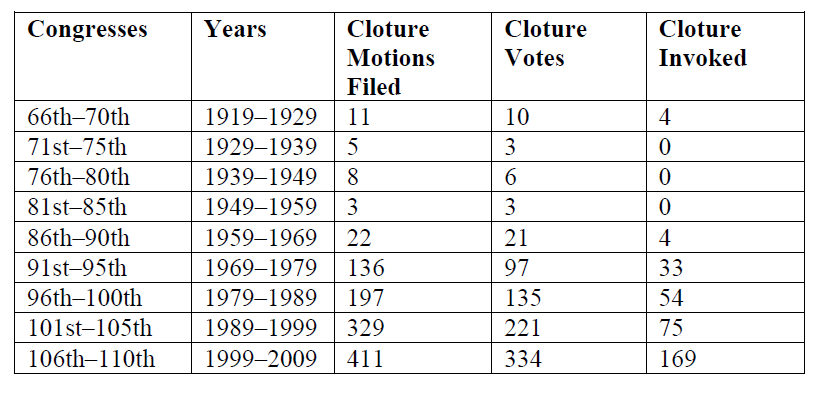

Josh Chafetz, in a 2011 law review article provided the following:

These data led him to state:

Cloture is now a de facto requirement for the passage of any significant measure—and this is a very recent phenomenon.

[…]

The trend is unmistakable—and a more fine-grained picture tells an

even starker story. Through the 109th Congress (2005-2007), there had

never been more than eighty-two cloture motions filed (104th Congress),

sixty-one cloture votes (107th Congress), or thirty-four invocations of

cloture (107th and 109th Congresses). In the 110th Congress (2007-

2009), there were one hundred thirty-nine cloture motions filed, one

hundred twelve votes on cloture, and cloture was invoked sixty-one

times.30 In other words, that one Congress had 69.5% more cloture

motions filed, 83.6% more cloture votes, and 79.4% more successful

invocations of cloture than any Congress had ever had before. And the

111th Congress (2009-2011) followed suit, with one hundred thirty-six

cloture motions filed, ninety-one votes on cloture, and sixty-three

invocations of cloture.

His conclusion of the article states:

The contemporary filibuster cannot be justified on the grounds of a Senate tradition of unlimited debate. The contemporary filibuster is not a mechanism of debate; it is a mechanism of obstruction, plain and simple.

And in recent Congresses, it has become a mechanism to be applied to

nearly every measure to come before the Senate, such that it can now

accurately be said that most measures require sixty votes to pass the

Senate.

Note that this analysis was written roughly a decade ago, and it has gotten worse since. (He also concluded in that piece that the filibuster is unconstitutional, which I don’t agree with, but that is another debate).

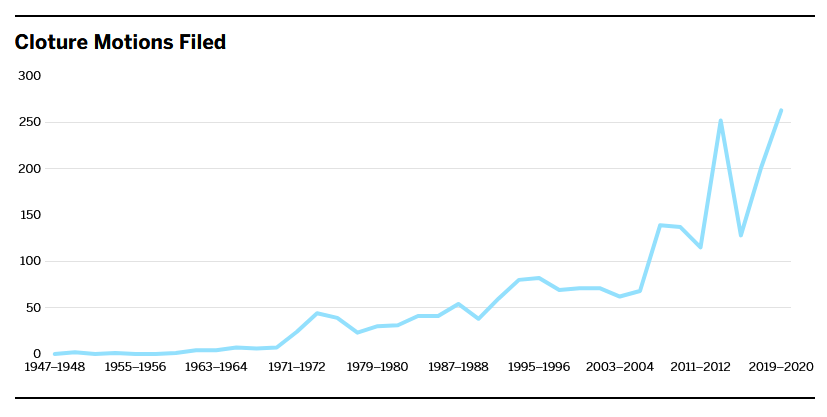

Chafetz’s data can be augmented from the Philip Bump piece I noted above (It is time once again to explain what the filibuster is and isn’t) wherein he noted for the recently growth in the usage of the mechanism:

From 1989 through 2006, about 7.8 percent of the roll-call votes cast in the Senate each year were for cloture. Since, a quarter of votes taken have been cloture votes on average. During the past six years, when McConnell led the majority, nearly a third of the votes cast were for cloture.

It’s gotten to the point that the filibuster is presented as a sort of intrinsic part of doing business in the Senate. In 2013 (back when cloture votes made up only 22 percent of roll-call votes), one senator even suggested that requiring 60 votes was simply how things should work.

Note that in 2019, after Democrats won control of the House that cloture votes were ~45% of all votes in the Senate.

The Brennan Center has some longer-term graphs:

Apropos of all of this, and to echo something a noted yesterday:

In short: none of the reasons given for keeping the filibuster are good, and really aren’t especially true. Republicans prefer it at the moment because they are the minority party in terms of the number of people represented in the Senate. And perhaps even more importantly, when the are in the power their main goals are judicial nominations and tax policy–both of which have non-filibusterable routes. Their main goal while in the minority is to obstruct.

It is a bad trade for Democrats to give away the ability to legislate when they have majorities for the possibility that they may need to obstruct legislation in the future.

And to be clear: I think it is better for our democracy that whichever party is in control of the legislature should the ability to legislate (even keeping in mind the numerous representativeness problems in the US Congress, especially the Senate). It remains true that that bicameralism itself creates sufficient brakes on runaway action, as does the executive veto.

In other words: legislating is difficult enough under normal conditions. There is no good reason to to make it nearly impossible.

We are letting a dishonest presentation of a false historical narrative that draws more from a Frank Capra movie made in 1939 than it does from political science to influence the operations of one chamber of the national legislature.

That’s nuts.

I would note a few of my older posts on this topic:

Yeah, I like it. If you win a majority, do the things you said you were gonna do, and own it. If you don’t do the things you said you were gonna do, you can’t blame the other guys. They couldn’t stop you. And if the things you do aren’t popular, live with the results.

I’ve had it up to here with the whole posturing extremist positions calculated to boost presidential aspirations thing.

Bill Lockyer, a long-time CA pol, oncer said, “Doing a good job is the best politics”. I tend to agree.

I agree, but someone needs to convince Joe Manchin.

I’ve slowly come around to this view, although I really don’t like 50% able to make massive changes.

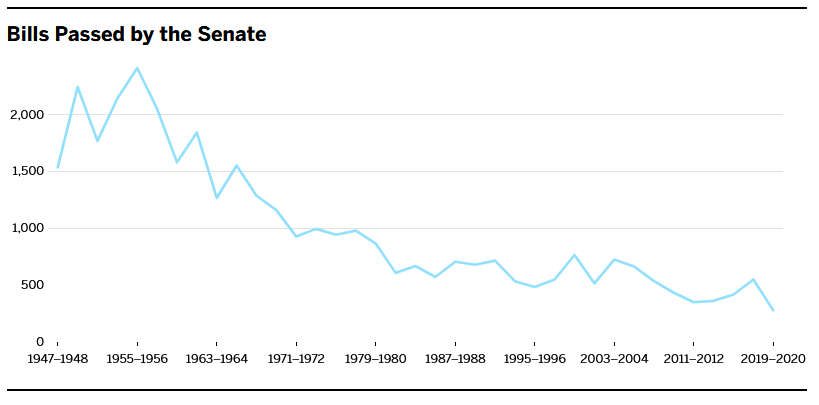

Tangential point: I wonder if the “Bills Passed by the Senate” graphic isn’t misleading? Hasn’t the trend been toward omnibus bills and away from single-issue legislation?

@James Joyner:

I just think that is the wrong frame. Major legislation, let alone truly massive change, is hard filibuster or no.

There is some definite truth to that, so it is a confounding variable that would need to be teased out. Still, the overall rate of legislation has declined.

As far as I can tell (or remember), the filibuster was supposed to be a speedbump in the road. It’s become a ginormous, Hadrian’s Wall blockade. Frankly, I’d be in favor of any step that would require the generally spineless weasels in the Senate (Congress too, for that matter), to actually put down their Froot-Loops, step up to the table and do the freaking job we’re paying them for.

I’m not a fan of the filibuster and am fine seeing it go. And if Democrats want to be the ones to get rid of it, that’s their choice and also fine by me.

But realize that this is a tool both sides will use and Democrats will have no legitimate right to complain when Republicans use it to their advantage – just as they’ve done with judicial nominations.

Recall that the current two-track protocol in the Senate — two major motions can be open on the floor at the same time — which led directly to the current form of the filibuster was introduced in 1967. The Dixiecrats indicated that they were willing (and able) to shut the Senate down for months, regardless of the consequences, in order to keep any more civil rights legislation from passing.

@James Joyner:

I would love to see some type of visualization of the percentage of bills that are sent from the House to the Senate that ultimately pass.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I think it’s also worth noting how many past examples of major legislation/massive change have gone through the budget reconciliation process in order to specifically side step the filibuster.

It’s 50%+1 in two branches of congress, elected very differently, and the presidency.

Yes, the Republicans might go crazy and eliminate social security or something. And that will hurt, they will get destroyed in the next cycle, and it will be undone.

It also means that Republicans will have to stop electing crazy people with the assurance that the crazy people won’t get their crazy shit done. Sometimes people have to face consequences.

@flat earth luddite: Even so,

creates a major obstacle–duly noted by Dr. Taylor, I will add–and we end up with deficit hawks who vote for record deficits when their party is in power and isolationists voting for “nation planting” under the same circumstances–all under the watchful eyes of voters who perpetually reelect the same lying weasels–and occasionally add to the problem by voting mixed government in a seeming plan specifically to thwart government from functioning.

When voters start caring that Congress is broken, they will start to demand action from the parties to address that and vote accordingly. Not seeing that in the immediate future (i.e. the likely life span of a nearly 70 year old with parents and grandparents who lived into their 90s). And this time, divided Congress keeps the bread and circus cycle going and the POC mostly in their place–and that’s good enough for most of the upper middle class and above of all ethnicities and colors. And they still run the show.

@mattbernius:

Knowing that bills would go to the Senate to die, I would expect that some of the bills the House passed were just performance. I don’t know what the right metrics are.

@James Joyner:

I would argue that the filibuster actually exacerbates the problem, or rather the hyper-partisanship that makes the filibuster such a go-to move. If the filibuster didn’t exist, a few Senators would be able to sway the legislation. When I read historical descriptions of bills passing, the sponsors didn’t know until the end whether they would get their votes or not. A lot would be done to satisfy someone who was leaning. But ever since Gingrich and Hastert and, of course, McConnell, there is no chance any Republican is going to support a Democratic initiative of any consequence. It’s just not going to happen. So the choices are to do nothing, or do it with only Democrats. And that cuts moderate Republicans completely out of the picture, and puts conservative Democrats in the glare of hideous publicity making it hard for them to play tough.

That chart is actually misleading. Republicans filibuster 100% of consequential Democratic initiatives. They don’t let anything significant get to the floor.

It didn’t used to be as bad on the Dem side, but the Gingrich 50%-plus-1-vote policy has completely taken over the party. Republicans load up every bill with things toxic to Democrats and even some Republicans until it will just pass. If a Dem votes for a Republican bill you can guarantee that it contains something that will cause him or her great trouble at the next election, and the Republicans will not hesitate to use it against them through proxies.

Bottom line, if we didn’t have the filibuster, a lone Senator or two could go against their party and have great influence to “moderate” the bill. But with the filibuster they need a significant number to work together, and if they can’t pull it off their legs will get cut out from under them.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

Oh, I know. Sigh… I just keep hoping for better, even tho’ I know there ain’t no pony in the stable. As both of us have frequently commented, there’s nothing wrong here that a better grade of people couldn’t/wouldn’t fix.

Or as that prophet Lucy Van Pelt once stated, “I love mankind, it’s people I can’t stand.”

@flat earth luddite:

From what I’ve seen of the history there’s no “it was supposed to”. Originally the Senate had a rule allowing senators to “move the previous question”, i.e. call the question, by majority vote, closing off debate and requiring a vote on the issue. According to WIKI Aaron Burr set out to clean up Senate rules and got this removed as redundant, since it wasn’t being used. Sometime later senators realized they could stall and there was no way to shut them off. This led to rules to close debate, but compromising with the factions who wanted to use it by requiring supermajorities. It wasn’t designed for any particular purpose, it just happened.

It’s another choke point in a process that already has many and another anti-democratic feature Republicans can use to support their power while in the minority.

@Andy:

I agree, but the charts above don’t show who used the filibuster, except that it’s gone way up under Moscow Mitch. I can’t claim to have done the analysis, but I believe it’s generally been used more by conservatives, Republicans and Dixiecrats. It’s another asymmetry.

@gVOR08: Thanks for the history, that was interesting. And another reminder that systems need constant upgrading, as there is no such thing as “static”. Even without rule changes, things get used in unintended ways and exceptions eventually become the rule.

Could the Senate alter the rules so a member’s vote matched the population they represent? Say with each Senator nominally representing half the population in their state.

Let’s round up to the nearest million, so CA represents 39,000,000 people, and then divide by 100,000 to determine the vote total. In California’s case, that’s 390 votes, or 195 per Senator. By contrast, Wyoming represents 582,000 people, meaning it has 5.82 votes, or 2.91 per Senator. Let’s be generous and say six votes and three per Senator.

A quick guesstimate is the country represents about 3,300 Senate votes, so CA would have a bit over 10% and Wyoming under one per cent.

The VP would retain their tie-breaking role, but ties would be far less common than they are now.

Ok, this won’t ever happen, I know that, but it would be a fair way of giving proportional representation and keeping the two senators per state hardwired in the Constitution 1787 Operating System.

Nothing prevents the press from stating how many people a Senate vote represents. This would make the disparity obvious.

The press won’t do that, either, expect here and there on occasion. maybe a web site could be set up to keep track of this, like the sites showing the national debt or the deficit, for instance. I’d do it myself, except I’ve zero skills in web design and management. Figuring out the population equivalents per vote is easy, and with a 50/50 Senate, many votes may be exactly the same over and over.

It would make for far different optics to read that a vote on a bill was 50R vs 50 D + 1 VP, than to read it’s, for example, 144 million R vs 187 million D + 1 VP.

@Kathy: The Constitution guarantees all states equal suffrage in the Senate, and includes a clause that says that can’t be amended.

@Michael Cain:

A quick reading tells me Article I Section 3, states “The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, chosen by the Legislature thereof, for six Years; and each Senator shall have one Vote.”

So, yeah, that would require amending the Constitution 🙁

I don’t see a clause which states this cannot be changed. there’s one saying Congress can’t pass a law altering the way Senators are chose by the states; that’s the closest I can find.

It was a quick reading, and I may have missed something.

On the plus side, I won the edit function lottery!

@gVOR08:

When the Senate convened in 2017, Moscow Mitch floated the idea of killing the filibuster and it was opposed by a fair number of R senators. The fear is that they would be required to take positions and vote on legislation that they wanted nothing to do with, because of the political heartache it would cause in their state. In the end, they only added judges to the votes that couldn’t filibustered.

During the last Congress, the House passed and sent over about 400 bills that were never acted on in the Senate, Mitch simply never put them on the docket or assigned them to a committee. The filibuster is allows senators to avoid responsibility.

Oh, and Joe Manchin has come out against the $15/hr minimum wage.

@Kathy: At the end of Article V, limiting amendments:

So, as a minimum, we’re talking about amending the way that amendments are done, and then we can talk about amending Article I. Once you get to amending Article V, well, that’s basically an admission that the whole schema is flawed and you might as well call a Convention.

@Michael Cain:

Thank you. the problem with hasty readings is that they’re mostly searches for key terms.

I wouldn’t say the US Constitution has to be junked and replaced, but it does need rather extensive revision. For our current purpose, what was meant by “state” in the 1780s is not what is meant now, nor how people really see things. That ought to change, and if it means a Convention, then it does; which is very easy for me to say.

@Andy:

Except to the extent that Democrats (and Republicans, for that matter) will sustain their rights to complain about the policy passed on the basis of sufficiency or efficacy or moral hazard, etc. Which is the national debate we should want to have instead of the debate we have now – ‘which side gamed the system to get their way with the most/least integrity?’

Since Democratic policy ideas are generally more popular than Republican ones, I’d expect Democrats to prefer that be the field of play.

The fact that Moscow Mitch didn’t get rid of the filibuster when he had the chance suggests to me that he in fact wants it in place, which is all the evidence I need to get rid of it.

Sure, it would give the GOP a chance to pass their bills, but their policies aren’t popular and maybe it’s time the American public gets a taste of what Republican lawmaking looks like.

@Kathy:

One of the things that I learned, working for a state legislature, is that how the political class in the state sees things and how their constituents see things may be very different. Not at some levels — if the people push hard enough, the legislators may come around on something like decriminalizing marijuana. On subjects that relate to further submission to Washington, not so much. And at least in non-initiation non-recall states, bet on the political class rather than the common folk.

@Michael Cain: That’s “initiative”, not initiation. The disconnect between my brain and my fingers continues to grow…

@Sleeping Dog:

I expect that the $15/hr minimum wage is being included to be removed, and give the conservative Dems a victory, so they can go back to their states and say “Well, thanks to me, you people will earn less.”

@Gustopher:

What puzzles me is why so many people are willing to cut their own throats simply to prevent CLANNNNNGGGGs from getting a raise. –

@Gustopher:

Manchin may have spoken first, but there’s a short list of states beside WV with one or more (D) Senators where $15/hr was dead on arrival: AZ, CO, MT, and NM to put names on that list. There is substantial evidence that $12.50/hr, phased in, and indexed to inflation, is achievable. I’ve been saying for a few years now, the national Democratic Party has to find some way to deal with the fact that their extraordinarily-thin Senate majority depends on keeping nine (D) Senators from Mountain West states happy.

@Michael Cain:

I don’t get how the minimum wage wasn’t indexed to inflation from the beginning. People making that little are the ones who suffer most from price increases, especially for basics like food, gas, and housing.

@Gustopher:

And to say to a metric sh*t-ton (is that an official unit of measurement?) of small business owners, we didn’t double your labor expense. There is more than one state with (D) Senators where $60k ($15/hr times full-time times two adults) exceeds the median household income. There’s a bunch of ballot initiative evidence that $12.50/hr, phased in over a couple of years, will be supported, but that $15/hr won’t be. Let CA and NJ do $15/hr, or $18/hr, or whatever they can get. Leave room for some poorer states to do a little less.

@Kathy: The federal minimum wage was established during a time of very low inflation, and applied to people who seldom voted. Legislators wanted the ability to come in from time to time and be noticed when they raised it. Note that the Social Security benefit — given to old people who vote in droves — had built-in cost of living increases after the last restructuring in the early 1980s, when inflation was an issue.

@Michael Cain: can you explain why a senator from Colorado would consider it doa when the minimum wage here is already 12.32 an hour with (iirc) an increase next Jan 1st?

@Thomm: Because they still need some rural and exurb votes. You and I know that what’s written in the proposed statute isn’t $15/hr immediately, but that’s the impression that’s being given. For a rural business, $12.32 to $15.00 is a 22% increase in labor cost (plus the hidden FICA share) in one go. Under CO’s minimum wage, the $12.32 only increases with inflation — the 90 cents/hr per year increases are done. Call it 2% a year and we’re on the order of 9-10 years away from $15/hr.

Maybe Bennet and Hickenlooper will take that chance, particularly if it’s part of a bill where they can bring back some other stuff for Colorado. Tester, Sinema, and Kelly, with much narrower wins? Probably not.

If I were Schuman and Pelosi, I’d be getting a big chunk of money for federal land management, fire fighting, and wildfire mitigation before and after fires ready to go. Fort Collins, where I live now, is muttering about millions of dollars per year to deal with the impact of last fall’s fires on federal land on the city’s water supply.

@Michael Cain: Gack, Schumer. Who can I see about improved connections between my brain and my fingers?

Relatedly, I don’t understand why the minimum wage discussions are always about a single $/hr. rate that would apply across the country instead of one that’s automatically pegged to median income, average prices, or PPP in each state, county, “economic zone”, or whatever. It would make a lot more sense and presumably get at least somewhat less resistance from small businesses in the lower income areas.