Why We’re Getting Worse At Construction

Affluence comes with a cost.

In yesterday’s NYT, Ezra Klein explores “The Great Construction Mystery.” To whit:

We’re getting worse at construction. Think of the technology we have today that we didn’t in the 1970s. The new generations of power tools and computer modeling and teleconferencing and advanced machinery and prefab materials and global shipping. You’d think we could build much more, much faster, for less money, than in the past. But we can’t. Or, at least, we don’t.

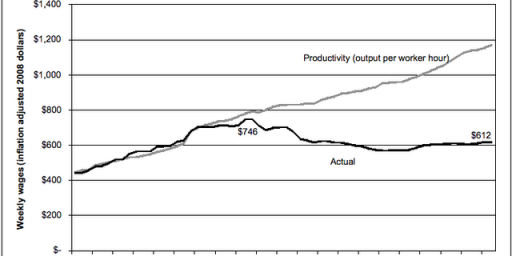

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, productivity in the construction sector — how much more could be done given the same number of workers and machines and land — grew faster than productivity in the rest of the economy. Then, around 1970, it began to fall, even as economywide productivity kept rising. Today, the divergence is truly wild. A construction worker in 2020 produced less than a construction worker in 1970, at least according to the official statistics. Contrast that with the economy overall, where labor productivity rose by 290 percent between 1950 and 2020, or to the manufacturing sector, which saw a stunning ninefold increase in productivity.

In typical Klein fashion, he looks at a cutting-edge economics paper and a half-century-old classic for clues. The entire piece is worth reading for nuance but much of the takeaway is here:

“When I first started back in the ’70s, you did one estimate on a project,” [Ed Zarenskit, who runs the market analysis firm Construction Analytics] told me. “You put it in, you got your bid, and if you won, you began construction. By the time I left in 2014, you did three estimates for every job before you even put the bid in. That becomes part of the cost of the job.”

Or take the job site, he said. “The safety features on jobs when I started in the industry were not even noticeable. Safety on a job today is incredibly different. You don’t walk across a beam, you walk around on a pathway marked for you to stay safe so you don’t fall off the side of the building. By the time I retired, one thing that took place every day, on every job site, was a mandatory 15 minutes of calisthenics before you start your workday. That’s totally nonproductive, but it led to fewer work site injuries during the day.”

And behind all that is paperwork, and paperwork, and more paperwork. “The work we do today takes hundreds more people in the office to track and bring to completion,” he told me. “The level of reporting that you have to send to the government, to the insurance companies, to the owner, to show you’re meeting all the requirements on the job site, all of that has increased. And so the number of people you need to produce that has increased.”

Aha! This is what conservatives have been saying for decades! It’s those daggum gumint bureaucrats with all their anti-business regulations.

Zarenski’s point isn’t that any of this is bad. If 15 minutes of daily calisthenics helps prevent a lifetime of back problems, it’s well worth it. The problem is that there’s more work at every level of the process, from the analyses done in the back office to the rules followed on-site.

So, yes, the regulations absolutely come at a high price. But, yeah, it’s hard to argue it’s not worth 15 minutes—even if multiplied by 5 workdays a week, 50 work-weeks a year, per worker—of unproductivity to prevent long-term damage to workers. Hell, it might even be more efficient in the long run if those workers stay healthy and productive longer. But these things add up.

I don’t have the expertise in construction work to know whether the marking system for high-beam work is going overboard. But I’m generally in favor of people not needlessly falling to their death in order to collect a paycheck.

This leads to a longish discourse into the late Mancur Olson’s classic work into collective action problems, the upshot of which, in Klein’s estimation, is this:

Olson almost completely missed the post-materialist turn in the politics of affluent countries. Some groups organize to get more of the pie, but many others organize to protect the environment, or to increase safety standards, or to preserve the feel of their communities, or to express their values. And much of this is good. It’s a gift of affluence, not a disease of affluence.

But Olson, who died in 1998, is right when he tells us that this gift comes with costs. And those costs concentrate in the areas of the economy in which the number of groups that have to be consulted mount. From this perspective, the productivity woes in the construction industry don’t seem so puzzling. It’s relatively easy to build things that exist only in computer code. It’s harder, but manageable, to manipulate matter within the four walls of a factory. When you construct a new building or subway tunnel or highway, you have to navigate neighbors and communities and existing roads and emergency access vehicles and politicians and beloved views of the park and the possibility of earthquakes and on and on. Construction may well be the industry with the most exposure to Olson’s thesis. And since Olson’s thesis is about affluent countries generally, it fits the international data, too.

Again, none of these insights is novel. The poor can’t worry about the long term; they have to survive today. Being able to defer gratification is a luxury of affluence.

For my entire lifetime—which roughly coincides with the decline in construction efficiency—we have had the luxury to worry about thing like clean air, clean water, and the health of workers. Or the extinction of the snail darter! To be sure, Democrats tended to place a higher priority on those things and Republicans a higher priority on economic efficiency but Nixon signed the Clean Air Act and founded the EPA and Bob Dole championed and George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act.

And NIMBYism certainly isn’t a partisan issue. The preservation of historic sites, green spaces, sightlines, and all the rest are perfectly understandable priorities that nonetheless conflict with other priorities. Everyone wants better infrastructure but nobody wants the inconvenience that comes with it.

The age-old solution—foisting the ill effects on the poorest and most underrepresented demographics—is also met with more skepticism these days. Still . . .

I ran this argument by Zarenski. As I finished, he told me that I couldn’t see it over the phone, but he was nodding his head up and down enthusiastically. “There are so many people who want to have some say over a project,” he said. “You have to meet so many parking spaces, per unit. It needs to be this far back from the sight lines. You have to use this much reclaimed water. You didn’t have 30 people sitting in an hearing room for the approval of a permit 40 years ago.”

Some of this is expressed through regulation. Anyone who has tracked housing construction in high-income and low-income areas knows that power operates informally, too. There’s a reason so much recent construction in Washington, D.C., has happened in the city’s Southwest, rather than in Georgetown. When richer residents want something stopped, they know how to organize — and they often already have the organizations, to say nothing of the lobbyists and access, needed to stop it.

There’s no doubt that’s true. It’s also the case, though, that Georgetown residents are simply less amenable to new construction. It’s already gentrified, so immune to gentrification. Southwest is relatively run-down and ripe for teardown.

This, Syverson said, was closest to his view on the construction slowdown, though he didn’t know how to test it against the data. “There are a million veto points,” he said. “There are a lot of mouths at the trough that need to be fed to get anything started or done. So many people can gum up the works.”

This also helps explain the curious finding that ends Syverson and Goolsbee’s paper. After looking at the states with the highest construction productivity, they note that the more productive states don’t seem to gain market share in the construction industry. That doesn’t make much sense if you assume that the difficulties of construction are primarily the organization of manpower and materials. It makes more sense if you assume that the frictions are in navigating local regulations, community considerations, neighbors’ qualms and politicians’ interests.

In the cities where I’ve covered politics closely, developers are fixtures in the local political scene. They have to be.

“My feeling is the guys that know the system have a much easier time getting through the system,” Zarenski said. “They know ahead of time what they have to come into the party with and how to speak to those people and how to satisfy them, and so it goes a lot smoother for them.” But a thorough knowledge of one city or state, and establishing relationships with its key stakeholders and decision makers, won’t necessarily translate to success in another.

I’m reminded of the Rodney Dangerfield character in “Back to School” and the need to grease the skids.

How do we get construction productivity rising again? I have no idea. Construction should become safer, more respectful of community concerns, and more environmentally sustainable as countries become richer and less desperate for growth.

To reprise an old saw yet again: Environmentally sustainable. Respectful of community concerns. Efficient. Pick two.

But it’s also true that many of the problems America faces — from decarbonization to affordable housing — would be a lot easier to solve if we were getting better at building, rather than worse.

For sure. But, again, it’s that we’ve gotten bad at building but that we have insisted on encumbering it with regulations that make it slower and more expensive. I suspect that Klein and I could find some of those regulations we’d be willing to relax—although I also suspect that we’d mostly chose different ones.

There’s also the fact that houses today are far larger, and far more complex. If I recall from discussions about this last week, the main metric is “square feet per person per year”. While tools and such have become more efficient, it’s greatly offset by the complexity of what’s being asked of the workers.

@Mu Yixiao: It’s a good point. Most of the houses in the neighborhood I grew up in were built in the 50’s and 60’s. The houses themselves and their roofs were as basic as they come – think of a sheet of paper tented along the long dimension and placed on a shoebox. The houses that are built in the same neighborhood today have dormers, attached garages, “wings” and their roofs have dozens of intersecting lines. A nightmare to design, build and maintain.

The person making that statement misunderstands what the word “productive” means because the injured worker is producing nothing while he or she is lying on the ground groaning and clutching his or her damaged appendage/torso. I will note in passing that the three or four people who rushed over to give aid, gawk, and whatnot are also similarly non-productive and move on.

Regulations don’t come out of nowhere–they are almost always enacted in response to a problem.

Let’s take insurers, for instance. They work off of mountains of actual data that show things like how fires start and how they move through a built structure. Reducing the amount of money they have to pay out to rebuild after a fire isn’t just a simple matter of profitability for them–the ratios determine solvency. So, through a combination of carrots (discounts for added fire protection) and sticks (higher premiums), they can adjust for risk. However, there’s an even bigger impact if they can push regulation that further reduces the risk of *any* home burning to the ground.

Safety regulations may seem ridiculous, but I’m willing to bet that whatever the regulation is, an insurer can point to either a loss or a lawsuit that led to its existence. Reduce the regulatory burden and you’ll need to increase liability premium costs.

I have been directly involved in the erection of, literally, hundreds of millions of dollars worth of construction. I have NEVER heard of anyone doing calisthenics.

If we have become worse at construction it because the people who used to build things have become Construction Managers – bankers – whose specialty is processing paper-work and collecting money. In turn the sub-contractors they hire to actually build things are the ones who have given them the lowest bid. The low bidder does not employ the best craftsmen.

As for regulations; sure, they suck. Sometimes they are silly. But in general they save lives. Carnegie had to hire to Pinkertons to “take care of” his workers who dared complain because they were dying in his steel factories. This is the world many Republicans would like to return to.

Regulations also keep buildings healthy, standing even. Next time you see an earthquake or hurricane in a third world country, and everything is levelled, you should realize it’s because they DON’T have building regulations.

The complaint about regulations I hear most about is the ADA. Of course most Republicans were born without the empathy gene.

@daryl and his brother darryl:

I think most building codes are reasonable. It’s all the stuff around the construction that can get out of hand–like the hyper-detailed environmental impact studies that can be required by any NIMBY in California.

“.. daggum gumint bureaucrats…. .all their anti-business regulations”

..anti-business regga-LAYshuns!!

fify

@Jen:

Yes.

I seem to recall a time, at least in the South, that the messaging from right-leaning pols fed a pretty basic attitude among their base–liberals want to control things for the sake of controlling things. The specific issues mostly fed off of that. The aspirational Reagan get the government out of the way and we will prosper message seemed secondary to that basic view.

I’m probably oversimplifying it, both because of my age at the time and the fading of details from my memory. It is different now, mostly because of changes in the centrality and sheer volume of information exchange, so motivating issues seem more specified. But I think that old basic spindle is internalized for a lot of GOP voters. And it works, because the value of regulations is often the absence of bad shit happening to their friends and family.

News articles treat productivity as a real, almost tangible thing, but it’s a derived number, albeit a rather simple one. It’s just GDP divided by total man-hours worked.

I read Klein’s column, and Ozark’s comments on it yesterday. Meanwhile, I live in what’s claimed to be the second fastest growing community in the country and I’m watching two new houses being built across the street. We’re recovering from hurricane Ian and numerous roofing crews are operating (ours is now scheduled for mid-March).

One can see that building quality has gone up over the years if for no other reason than that in FL building codes were tightened up post Hurricane Andrew. looking at damage, newer buildings clearly held up better. But also one can’t help but observe the building and roofing crews look to be heavily immigrant. Not something I’ve researched, but I expect most small builders price their houses on simple markup, land and construction cost plus a percentage profit. So if they use $15/hour labor instead of $30 labor their price goes down. And so does their “productivity”.

Something similar seems to have happened through COVID. We laid off low paid waitresses and store clerks but retained well paid accountants and college professors. And voila, productivity went up. Really a matter of wages and pricing structures, not “productivity”.

Recall that Nixon created the EPA because he didn’t trust environmentalists at all and he wanted all of them in one place in the federal government, rather than scattered across a dozen agencies, to better “keep on eye on them.” Nixon’s EPA was pretty toothless. Meaningful EPA regulations and enforcement authority were added by Congress some years later.

I wonder if there isn’t another way of looking at this that is supported by the data. I started wondering because of remarks by Zarenski quoted above to the effect of people who know the territory do better.

This sounds like “barriers to entry”, which is a classic method of cartelization. So, is the construction business cartelized? Perhaps with a big assist by proliferating power centers that can put their oar in – created for the purpose of improving things? As we know, cartels exist for the purpose of charging higher prices.

I’m all for many of these regulations which seem in line with my values. And I ask myself what might happen if we made an effort to streamline all the paperwork needed for some of these projects and make only one or two authorities that over see projects instead of a dozen who can put in their oar.

I think it’s likely that most of those about to lose their veto power are going to scream to high heaven about how the fix is in, and everything will get worse, and the needs of the people will be ignored.

Sigh. I wish I knew a better way forward.

My street (Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles) is maybe half a mile long and there are three vacant, buildable lots that have been sitting there for at least three years. One of those lots (next to mine) has unencumbered views of the mountains in one direction and the Hollywood sign in the other, and it’s just weeds and occasionally coyotes. There’s also an unfinished house, looks like it just needs appliances and flourishes. This in one of the historically hottest real estate markets in the country. Any build on these lots would be north of two million – and nothing. I know construction in California comes with all the regs, but jeez, just paying property taxes on unimproved buildable lots strikes me as bad business.

@Michael Reynolds: I’ve seen similar things in other areas, and they don’t have to be expensive areas to suffer the same problem. Heck, the neighborhood I grew up in was an ocean of 50×100 foot lots laid out in a huge grid, all of which were built up by 1965… except for the occasional plot scattered here and there. Some of these went undeveloped for decades. In fact, I just looked and one is still there, although it looks like there is a lawn on it now, but no house. I can understand how this happens for a while. There are people who have investments and the money and people to manage the taxes but who just don’t or can’t deal with them or make any decisions. But eventually those people die off and the estate is sold. Of course, sometimes the kids end up fighting over it for years and years, but even so, that has to end some time.

Up to the early 90s new houses very typically had Plam counters, linoleum floors, no crown molding to speak of, the bathrooms had simple faucets, the outside trim was basic but functional. All these things require more labor as well. I could go on and on, but the bottom line is it was an order of magnitude cheaper than the finishing that is expected today. Anybody looking at one of those houses today would demand a complete gut and re-do, with stone and oak floors….and a $100k kitchen.

It’s become so much the new “norm” it’s hard to find a house fitted out like they were in the mid-20th century, so I suspect the authors are taking it for granted.

As an architect and construction manager, my two cents:

Regulations have some explanatory power, but not very much.

The biggest factor is that unlike other industries, construction has not become automated and industrialized.

A worker today builds a building very much like they did a century ago, site assembling individual pieces on site by hand.

True, things like drywall and plywood have replaced individual boards and lath and plaster, and screw guns can install in minutes what would have taken a day. But like regulation, we are talking about small increases (or decreases) in productivity, not the big leaps that occurred in other sectors.

But still, its like assembling a one of a kind automobile each time, or re-typing a memo with a better typewriter instead of emailing it.

Notice the break point, in the 70s and 80s when computers and offshoring and automation intermodal transportation were transforming and accelerating other industries. There was no comparable shift in construction.

Prefabrication is here now, and modularized apartments are happening. But still not yet enough to accelerate productivity the way electronics did to office work or automation did to factory work.

I’d enjoy OzarkHillbilly’s perspective on this.

@CSK: I would, too. Must be Granddaughter Day.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: That’s what I was figuring, too, I seem to remember it being on Monday’s. He’ll check in tomorrow, I’m sure!

@CSK: @Just nutha ignint cracker: It was GD day.

At this point, all I can say is that when I came into the biz in the 70s, carpenters were disposable. Over time things improved but still we cursed every single new safety reg with our every breath because it was a pain in our arsses. Over time, by 2020 a cops life finally became more dangerous than a carpenters, (bureau of labor statistics) and that was only because of covid (not that anybody ever wondered if I was coming home at the end of the day). (my ex might have prayed I wouldn’t)

When I started, iirc, 2,000 sq ft of drywall a day was acceptable (maybe it was 2500/day) . My last drywall job, they expected 4,000 sq ft a day and I gave it to them.

Over the years I broke more bones than I can count. Ribs, fingers, ankles, wrists, vertebrae, and more. I couldn’t even begin to count the number of stitches I received. The last job I worked I couldn’t even grip the steering wheel of my car at the end of the day and realized that I hadn’t been able to for years. I got laid off from that job because I kept tearing the connecting cartilage between my short ribs. The assistant super asked me how old I was and without thinking I answered, “55.” A week later, I was gone. Yeah… Age discrimination anyone?

The punch line is a week after that I was back. They needed somebody who was certified to operate a Lull (4wd fork lift) and their laborer (who was much better than I) had never bothered getting certified. So I got another week and half’s pay out of those mf’ers.

Long story short: We had to produce more and more every f’n day, and we did.

My last drywall job, I managed to hit the minimum, some days s a little bit more, others a little bit less. One day a new carpenter was hired and the foreman dumped him on me to show him the ropes. He was a chatterbox, never shut up. Finally he asked, “Tom, what do you like?”

“Peace and quiet.”

Yeah.

After a while he asked, “What are we supposed to do every day?”

“2 units.” I replied (about 4200 sq ft.)

He looked at me with wide eyes and said, “I can’t do that!” I shrugged and he walked out the door and off the job.

A month later I asked the big boss for a day off every week to help take care of my Alzheimered old man while my mother went thru open heart surgery. A few days later I got my lay off check. My foreman said when handing me the check, “Don’t worry, you’ll be back in a week or 2.”

All I could say was, “No, I won’t.”

May I suggest that you look at this company’s products.

As I understand it, their efficiencies sell for about 50K (plus transportation). Elon Musk lives in one from time to time, down near his launch site.

Recently, they showed off a 3-bedroom prototype that they plan to sell for about 150K.

Their designs have one clever trick: They fold up for transport so they can be delivered by ordinary trucks. They can be installed, on site, in hours.

I haven’t done the arithmetic, but these strike me as significant advances in construction productivity.

And then what?

No, you haven’t.

@Jax: Always on Mondays. MawMaw is very insistent, these days are the ones we build our relationships with our GD’s from now until the day we die.

She is not wrong. In fact, she couldn’t be more right.