A New Gilded Age?

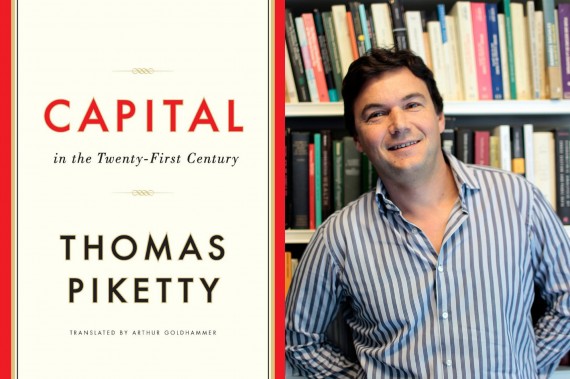

Thomas Piketty's Capital in the 21st Century is making quite a splash.

Thomas Piketty, a professor at the Paris School of Economics, is making quite a splash with the English-language publication of what Paul Krugman terms “his magnificent, sweeping meditation on inequality,” Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Indeed, Amazon is temporarily out of stock.

Krugman lavishes much praise on the author and the book for the New York Review of Books.

[H]is influence runs deep. It has become a commonplace to say that we are living in a second Gilded Age—or, as Piketty likes to put it, a second Belle Époque—defined by the incredible rise of the “one percent.” But it has only become a commonplace thanks to Piketty’s work. In particular, he and a few colleagues (notably Anthony Atkinson at Oxford and Emmanuel Saez at Berkeley) have pioneered statistical techniques that make it possible to track the concentration of income and wealth deep into the past—back to the early twentieth century for America and Britain, and all the way to the late eighteenth century for France.

The result has been a revolution in our understanding of long-term trends in inequality. Before this revolution, most discussions of economic disparity more or less ignored the very rich. Some economists (not to mention politicians) tried to shout down any mention of inequality at all: “Of the tendencies that are harmful to sound economics, the most seductive, and in my opinion the most poisonous, is to focus on questions of distribution,” declared Robert Lucas Jr. of the University of Chicago, the most influential macroeconomist of his generation, in 2004. But even those willing to discuss inequality generally focused on the gap between the poor or the working class and the merely well-off, not the truly rich—on college graduates whose wage gains outpaced those of less-educated workers, or on the comparative good fortune of the top fifth of the population compared with the bottom four fifths, not on the rapidly rising incomes of executives and bankers.

It therefore came as a revelation when Piketty and his colleagues showed that incomes of the now famous “one percent,” and of even narrower groups, are actually the big story in rising inequality. And this discovery came with a second revelation: talk of a second Gilded Age, which might have seemed like hyperbole, was nothing of the kind. In America in particular the share of national income going to the top one percent has followed a great U-shaped arc. Before World War I the one percent received around a fifth of total income in both Britain and the United States. By 1950 that share had been cut by more than half. But since 1980 the one percent has seen its income share surge again—and in the United States it’s back to what it was a century ago.

[…]

Piketty has written a truly superb book. It’s a work that melds grand historical sweep—when was the last time you heard an economist invoke Jane Austen and Balzac?—with painstaking data analysis. And even though Piketty mocks the economics profession for its “childish passion for mathematics,” underlying his discussion is a tour de force of economic modeling, an approach that integrates the analysis of economic growth with that of the distribution of income and wealth. This is a book that will change both the way we think about society and the way we do economics. [emphases all mine-jhj]

Coming from a holder of the John Bates Clark Medal and the Nobel, that’s high praise, indeed.

The central theme of the book?

The general presumption of most inequality researchers has been that earned income, usually salaries, is where all the action is, and that income from capital is neither important nor interesting. Piketty shows, however, that even today income from capital, not earnings, predominates at the top of the income distribution. He also shows that in the past—during Europe’s Belle Époque and, to a lesser extent, America’s Gilded Age—unequal ownership of assets, not unequal pay, was the prime driver of income disparities. And he argues that we’re on our way back to that kind of society. Nor is this casual speculation on his part. For all that Capital in the Twenty-First Century is a work of principled empiricism, it is very much driven by a theoretical frame that attempts to unify discussion of economic growth and the distribution of both income and wealth. Basically, Piketty sees economic history as the story of a race between capital accumulation and other factors driving growth, mainly population growth and technological progress.

Again, Krugman finds this ground-breaking:

Capital in the Twenty-First Century is, as I hope I’ve made clear, an awesome work. At a time when the concentration of wealth and income in the hands of a few has resurfaced as a central political issue, Piketty doesn’t just offer invaluable documentation of what is happening, with unmatched historical depth. He also offers what amounts to a unified field theory of inequality, one that integrates economic growth, the distribution of income between capital and labor, and the distribution of wealth and income among individuals into a single frame.

Now, here’s the interesting twist: none of this explains what’s happened in the United States.

[T]he main reason there has been a hankering for a book like this is the rise, not just of the one percent, but specifically of the American one percent. Yet that rise, it turns out, has happened for reasons that lie beyond the scope of Piketty’s grand thesis.

Piketty is, of course, too good and too honest an economist to try to gloss over inconvenient facts. “US inequality in 2010,” he declares, “is quantitatively as extreme as in old Europe in the first decade of the twentieth century, but the structure of that inequality is rather clearly different.” Indeed, what we have seen in America and are starting to see elsewhere is something “radically new”—the rise of “supersalaries.”

Capital still matters; at the very highest reaches of society, income from capital still exceeds income from wages, salaries, and bonuses. Piketty estimates that the increased inequality of capital income accounts for about a third of the overall rise in US inequality. But wage income at the top has also surged. Real wages for most US workers have increased little if at all since the early 1970s, but wages for the top one percent of earners have risen 165 percent, and wages for the top 0.1 percent have risen 362 percent.

So, what gives?

What explains this dramatic rise in earnings inequality, with the lion’s share of the gains going to people at the very top? Some US economists suggest that it’s driven by changes in technology. In a famous 1981 paper titled “The Economics of Superstars,” the Chicago economist Sherwin Rosen argued that modern communications technology, by extending the reach of talented individuals, was creating winner-take-all markets in which a handful of exceptional individuals reap huge rewards, even if they’re only modestly better at what they do than far less well paid rivals.

Piketty is unconvinced. As he notes, conservative economists love to talk about the high pay of performers of one kind or another, such as movie and sports stars, as a way of suggesting that high incomes really are deserved. But such people actually make up only a tiny fraction of the earnings elite. What one finds instead is mainly executives of one sort or another—people whose performance is, in fact, quite hard to assess or give a monetary value to.

Who determines what a corporate CEO is worth? Well, there’s normally a compensation committee, appointed by the CEO himself. In effect, Piketty argues, high-level executives set their own pay, constrained by social norms rather than any sort of market discipline. And he attributes skyrocketing pay at the top to an erosion of these norms. In effect, he attributes soaring wage incomes at the top to social and political rather than strictly economic forces.

Krugman adds:

There’s a lot to be said for this diagnosis, but it clearly lacks the rigor and universality of Piketty’s analysis of the distribution of and returns to wealth. Also, I don’t think Capital in the Twenty-First Century adequately answers the most telling criticism of the executive power hypothesis: the concentration of very high incomes in finance, where performance actually can, after a fashion, be evaluated. I didn’t mention hedge fund managers idly: such people are paid based on their ability to attract clients and achieve investment returns. You can question the social value of modern finance, but the Gordon Gekkos out there are clearly good at something, and their rise can’t be attributed solely to power relations, although I guess you could argue that willingness to engage in morally dubious wheeling and dealing, like willingness to flout pay norms, is encouraged by low marginal tax rates.

Still, he cuts Piketty some slack:

Even if the surge in US inequality to date has been driven mainly by wage income, capital has nonetheless been significant too. And in any case, the story looking forward is likely to be quite different. The current generation of the very rich in America may consist largely of executives rather than rentiers, people who live off accumulated capital, but these executives have heirs. And America two decades from now could be a rentier-dominated society even more unequal than Belle Époque Europe.

The remainder of the essay is a discussion of public policy options, mostly the shared preference of the two economists for redistribution via the tax system and skepticism that we’ll actually see it happen to their satisfaction on either side of the Pond owing to the outsized political influence of the wealthy.

As wildly successful as the book already is, though, its nuance seems to be lost on, well, everyone who isn’t a professional economist. Take this gushing column from The Guardian‘s Heidi Moore:

Piketty’s sublimely nerdy book, packed with graphs, statistics and history, is all evidence for an immensely depressing theory: that the meritocracy of capitalism is a big, fat lie.

Piketty’s research, which is immaculate, reaches back hundreds of years to establish a simple thesis: the American dream – and more broadly, the egalitarian promise of Western-style capitalism – does not, and maybe cannot, deliver on its promises. That, he writes, is because economic growth will always be smaller than the profits from any money that is invested. Economic growth is what we all benefit from, but profits from invested money accrue only to the rich.

The consequences of this are clear: those who have family fortunes are the winners, and everyone else doesn’t have much of a shot of being wealthy unless they marry into or inherit money. It’s Jane Austen all over again, and we’ve just fooled ourselves that the complicated financial system has changed a thing.

This is a deep point. Many American households, if they are lucky, will grow their wealth at the same rate as the economy. But, because the wealthy are growing their fortunes at a much faster rate, no one else can ever catch up.

Let’s repeat that: no one else can ever catch up.

Except, as even Krugman readily points out, none of this is true! Indeed, most of the super wealthy class in America at least are in the finance sector. Whatever other criticisms might be made of that group, that they inherited their riches is not among them.

The discussion that Piketty and others have made possible, and that Krugman and others have helped popularize, is worth having. But it’s likely to be steered in the direction of the stupid by the likes of The Guardian. That’s a pity.

Hat tip: Dan Drezner

I look forward to reading it (I will wait for the paperback or the used book market to pick it up). It is nice that someone took a (somewhat?) novel approach to shed new light on Economics.

The “out-sized political influence of the wealthy” is AFNAB to conservatives.

Conservative men claim concern for modern manliness, yet accept their fate as mere servants to their wealthy betters so unquestioningly.

It’s almost a sure thing, predictable, that conservatives will depict Piketty’s book as class warfare and perhaps as Marxist. Yet it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we are now in a new Gilded Age.

Each of the last 3 periods of economic boom since the 1980s has been successively larger than the preceding one, each following recession has been been deep, and the most recent the most severe since the Great Depression. All the while a disproportionate share of wealth and benefits of these booms has been captured by the most wealthy members of our society. The statistics are there for all to see – middle class income has remained relatively stagnant since the 1970s, and many households have two wage earners in order to support a middle class lifestyle.

We’re there, we’re in a Gilded Age – and it’s not so far removed in style from the era of the Robber Barons, and the time when a guy like Jay Gould could go to a state house with a case of money and openly buy off legislators. We have one political party – the Republican Party – that virtually trips over itself to worship the most elite and wealthy individuals in our country. We have an individual who purchased one Hawaiian Island for $500M-$1B. The Supreme Court has recently issued decisions that have opened the floodgates for our national politicians to solicit and receive millions of dollars from most elite and wealthy people in America. The Court has effectively said that free speech is a commodity like all others, and the inference is clear, extremely wealthy people potentially have much more free speech than other less wealthy Americans.

So Piketty is a genius that will revolutionize economics, but only to the extent his conclusions agree with Krugman’s political agenda.

@al-Ameda:

Just to point out, Dems are not exactly immune to the ministrations of great wealth either, as shown by the current occupant of the White House who recently held a gathering for newly minted Trust Fund Babies.

@Stormy Dragon:

Well, no. The first part of the analysis is supported by hard data thanks to Piketty’s invented technique. The second part is conjecture from that analysis. It’s almost by definition less rigorous.

Another thing that Piketty and Krugman don’t address is there are simply not going to be enough jobs for everyone who wants or needs one. Manufacturing is increasingly automated often out of necessity. Even the service industries are being automated. So the question is how do we as a society address this issue?

A new Gilded Age? Well, at least that explains why the most conservative Democrat since Grover Cleveland sits in the White House. Next up: Hillary McKinley Clinton

@OzarkHillbilly:

True enough. However Republicans just ran an entire presidential campaign based on demanding greater appreciation of the top One Percent, and sneering at the bottom 47% whom they perceive to be parasites who don’t carry their weight.

@edmondo:

Wow, so a Hawaiian-Kenyan-Socialist-Marxist is a Conservative Democrat?

@Ron Beasley: until we stop deferring maintenance on our infrastructure, I don’t think we can seriously talk about there being not enough jobs because of automation and other structural changes to the economy.

The jobs are there, we are just too cheap to pay for them to be done, since that would mean higher taxes.

The Guardian is parsing economic research through an ideological filter.

Nothing new to see here, aside from the economic research. I’m not saying economists can’t be biased – Jesus, they can be the most biased – but when the data is good and the conjecture isn’t baseless, we have to come up with a different excuse for not listening to them.

My favorite is, “The profession of economics is composed of people who poorly understand mathematics trying to grasp the most complex undertaking of human society,” but calling him a Marxist is probably what most will go with. Hey, he’s French, there’s a whole load of stereotypes to throw at him!

@Gustopher: The conservatives will refer fixing our crumbling infrastructure as “make work,” the new WPA. I still drive over a bridge built by the WPA almost everyday and yes it’s in serious need of replacement. The conservatives hate of FDR may still exceed their hate for Obama.

@edmondo:

Can you really claim that President Obama is less progressive that President Clinton. The Clinton Adminstraiton was about as close as the U.S. ever is going to get to libertarian policy and both parties just want to run away from it.

What part of the economy did the Clinton Administration succeed in de facto nationalizing.

Everyone seems to want to talk about Piketty’s writing but there has been almost no discussion of developing new policies based upon the writing. A wealth tax probably will not work in the long term and I doubt if the Democrats want to go back to the NYC of the 19870’s by bring back the tax rates of the 1970’s.

@superdestroyer:

Nor, back to the days when an openly communist war hero – Dwight Eisenhower – was president and the top marginal tax rate was 91%

@al-Ameda: No argument at all, tho I have yet to read the Princeton report nor will I comment to what extent there is the very real and important difference. Just want to note that there is not as much of a difference as I would like.

@superdestroyer:

Ummm, maybe that is because serious people want to fully read it, understand it, digest its implications, its strong points and its weak points, etc etc etc before they propose anything based on it? Ya think?

The second and last course I took in economics was taught in winter semester 1959. It was devoted entirely to wage theory. According to the text, your pay was based on your marginal utility to your firm. It was understood that determining an employee’s marginal utility was difficult, but that employers all used the concept in setting pay even if they’d never heard of it.

On the last day of class somebody asked the professor (Al Mandlestamm, who passed away recently – see http://tinyurl.com/m466b89) what he thought. Mandlestamm said that the marginal utility theory of pay was incomplete in that it didn’t take public opinion into account. He felt that the Depression and WW II had created a climate of opinion in which shared sacrifice was the norm, and that salaries that were too far out of line would incite wrath from the politicians and scorn from the public. I remember all this because I had to look up “norm” after class.

He may have been right then, but things are certainly different now. I find it hard to understand why people barely hanging on, e.g. Joe the Plumber before he became famous, aren’t incensed by the outsized pay of business executives and the amazing fortunes of people like the Waltons, who’ve inherited everything they have. Do a majority of Americans think that capitalism would collapse if marginal tax rates were increased? Or that it’s immoral to subsidize health insurance? Or that Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Food Stamps erode the self-reliance of the poor and encourage them to live a life of sloth? It seems that way, and it’s beyond me. Maybe Eric Florack or somebody like him could explain.

My understanding is that “Joe the Plumber” is currently working a factory job. A man who, according to right wing mythology, would be a successful entrepreneur if only the government got out of his way apparently lacks the savvy to parlay national fame and a sympathetic audience that is spoon fed by Fox News into a career as a D list celebrity.

@Ron Beasley:

We are simply going to have to de-couple jobs from income in one manner or another, possibly by a universal guaranteed income. If we have, say, 100 people of working age, but we can produce all the goods and services we need with the labor of only 40 people, there has to be some other way for those 60 people to support themselves.

@anjin-san:

Not only that, but a unionized factory job.

@al-Ameda: “Wow, so a Hawaiian-Kenyan-Socialist-Marxist is a Conservative Democrat? ”

If he can simultaneously be an atheist socialist and an islamofascist, is there anything beyond his cruel grasp?

@Barry:

Nothing is beyond the reach of someone who is also simultaneously a weak ineffective leader and a grasping tyrannical power-hungry dictator.

@al-Ameda: The original reasoning for the high tax rate was concern about what the American people would spend their very large savings on as the war drew to a close and rationing was ended. The choice was made to dampen inflationary pressure by reducing purchasing power of the wealthy, allowing what would become the middle class to spend more freely.

Taxation was never the policy of choice for reducing inequality per se, rather the government pursued a policy of strong wage growth to reduce the national rate of profit. Doing so forced businessmen to work as they could not afford to live solely from the interest of their investments.

@superdestroyer: “Democrats want to go back to the NYC of the 19870′s”

I do, it’d be like Futurama! Imagine NYC of the 197th century!

@Rafer Janders:

But what will be the long term consequences of having people on the dole. Also, how much better will the standard of living have to be for people to decide to work rather than be on the dole.

A dole society will probably cause a huge number of foreseeable problems that will lower the quality of life for most all Americans.

@Barry:

All of the hipsters and progressive in NYC need to look up what the quality of life was in NYC in the 1970’s. When people are paying high marginal taxes, there is much less money for luxuries and the jobs that supplying those luxuries creates. A high marginal tax rate probably means a much smaller market for anything artisan, organic, design, fair trade, etc. It is amazing how progressives have forgotten what the lack of wealth will eliminate.

@superdestroyer:

No, yeah, you’re right….we should institute much higher, confiscatory tax rates on investment income so that people are forced to work and won’t be able to live off their interest and dividend gains. We have to get people like Paris Hilton off the inheritance dole.

@superdestroyer:

Yes, we might have to live in the dystopian hellscape that was so well represented in movies such as “Annie Hall” and “Manhattan.”

@superdestroyer:

Yeah, nothing artisanal, organic, well-designed, or fair trade in high marginal tax rate societies such as Denmark, Sweden or Germany….

@Rafer Janders: @superdestroyer: I don’t see a complete decoupling as the solution. I think a reduction in the hours worked, perhaps 20 instead of 40 combined with a universal guaranteed income but you still have to work to get it. The reduction of work hours in France years ago was an attempt to increase the number of jobs not give workers a free ride. Of course the universal guaranteed income will require income redistribution which will result in howls from the conservatives but without it the 1% may find themselves being marched to the guillotine circa early 19th century France.

@superdestroyer:

California and NY have far higher marginal tax rates than Texas and Oklahoma. Between the two camps, which has the greater demand and market for anything artisanal, organic, designed, or fair trade?

@Ron Beasley:

I’m fine with that, or with a redirection in the type of work. Maybe we need fewer clerks and drivers and factory workers and cashiers and more gardeners and artisans and teachers and nursing home aides. Less effort devoted to adding increasingly marginal value to profit-making businesses and more effort devoted to beautifying our society and making life easier for everyone.

@Rafer Janders:

Care to provide a cite. And how much does the government subsize such endeavors in those countries.

Well, probably a lack of starvation. And crime waves caused by people trying to get money/food so that they won’t starve.

Oh, and also we will have to live without have-nots killing haves because utter desperation with no prospect of a better life has driven them into a homicidal rage.

@Ron Beasley:

Of course, that just means that the workers who can work more than 20 hours a week just get richer. Image the advantage corporate lawyers who bill by the hour will have over civil servants who work 20 hours a week.

Also, this will just bring back the mom and pop businesses who will have a massive advantage over chains. They can work all the hours they want and out compete business where managers can only work 20 hours a week.

How much time did you spend in NYC in the 70s?

@Rafer Janders: Heck, what about revamping the economy entirely and start paying caretakers some money?

I’d love to have a steeply progressive tax rate, take that money, and provide steady salaries for people (usually women) who do such stuff like take care of their kids or other people’s kids, ditto for taking care of old people.

It seems to me that taking care of your old mother should be considered at least as rewarding to society as coming up with the next financially engineered synthetic CDO.

There’s a lot of actual work out there that needs to be done. The problem is–we don’t identify it as work or think its practitioners should be paid.

P.S. I point out again that even from the beginning, GNP has not been formulated to include the worth of unpaid care taking and works in the home (mainly because they couldn’t figure out how to measure it.) Which means that a lot of the so-called growth in GNP the US manifested in its GNP statistics hasn’t been actual growth at all, but simply an artifact of the movement for outsourcing tasks such as cooking and childcare from the home to elsewhere. Housewife/moms contributed a heck of a lot to the US economy and very little of it has ever been measured.

P.P.S. Housework and SAHMing does have a yin-yang aspect to it. “Work and standards expand to fill the time available.” A heck of a lot of what housewives used to have to spend a full day doing has been minimalized with labour-saving devices such as linoleum, vacuums, and washing machines. Ditto for the much smaller families we now have. Which has caused a lot of bored housewives to try to fill up their days with Martha Stewart busywork and helicopter parenting, none of which is actually productive to society…..but I digress.

@anjin-san:

The history of the government giving people welfare and its effect on reducing crime are not proven. Are you really taking the position that the crime rate in public housing projects was low due to the income provided by the government.

If people who are working have items that people who are not working do not, there will be crime. It is conceivable that the crime rate would go up due to a large number of non-employed people wanting to increase their standard of living by doing something that the government does not regulate or tax. If nothing else, the amount of crime due to substance abuse would probably go up due to increased use of drugs and alcohol.

Do you have reading comprehension problems? I took the position that poor people are not randomly rage-killing middle class and rich folks because of the income provided by the government, and that crimes committed by poor folks, while hardly trivial, are not out of control and are not a threat to the overall stability of our society – again, because of the income provided by the government.

@superdestroyer:

It’s amazing, isn’t it, that conservatives are extremely worried about the corrosive moral and social effects that not working for income will have on the middle and lower classes, but not at all concerned about the corrosive moral and social effects that a life of leisure has on the wealthy and powerful….

@superdestroyer:

Do I care to provide a cite for the claim that Denmark, Sweden and Germany are well-known for artisanal, organic, well-designed, and fair trade goods?

Um, no. And I also don’t care to provide a cite for the claim that there are a lot of coffeehouses in Seattle, that Brazilians love soccer, that sushi is popular in Japan, or for any other blazingly obvious well-known facts about the world.

@superdestroyer:

Yes, just imagine it. It will be nothing at all like we’ve ever experienced in America before, a brave new world where corporate lawyers will have much more money than civil servants….

@superdestroyer:

Oh no!!!

@superdestroyer: “But what will be the long term consequences of having people on the dole.”

The long term consequences will be awful. In fact, we can see them now. Go to northern Michigan or Appalachia or the Ozarks and you’ll see people without hope. Or try reading Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010, by Charles Murray.

The point I’d like to make here is that the US is competing with low wage countries — China, India, and Bangladesh, for example — and trying to beat them by lowering our wages to their level is self defeating. I don’t know if we can ever bring back our manufacturing supremacy, but we have no hope of doing so unless we improve our infrastructure and our human capital. We need spending on roads, bridges, railroads, protection against flooding, internet capacity, health, education, and a host of other things. Doing so costs money, and paying for it by cutting services to the poor and the middle class will dampen consumer demand and weaken our economy even further. I can’t get you to see this because you’re fixated on the injustice of the government taking your money and spending it on people and things you deem unworthy. So I’d like to ask, what’s your solution? Is it ending Food Stamps, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Medicaid, and assuming the poor will will work harder? Is it relying on the magic of the market to protect us against hurricanes? If that’s what you think, say so. And kindly provide historical examples showing that your approach works.

@anjin-san:

I take that you did not think about the influence that welfare programs have had in the past on crime. I take it that you did not think about the crime level in public housing projects in urban areas of the U.S.

I guess when one if a progressive, one does not have to think about all of the possible impacts of one’s pet policy proposal. I guess feeling good about one’s idea is enough.

@Rafer Janders:

When one can easily cheat on your taxes, one’s business is going to have a massive advantage over those corporations who just cannot cheat of their taxes. California has a massive problem now with the mom and pop business cheating on their taxes (think of the tradesman who wants to be paid in cash). Image how much worse it will be in a dole economy.

@superdestroyer:

Welfare payments and low-income housing subsidies caused crime in the housing projects?

@Rafer Janders:

I worry about the corrosive moral and social effects of both. The Investment Robber Barons of this New Gilded Age (thanks OTB for cluing me in to this whole conversation) and their proud continuance of the leisure class tradition upsets me. There is something inherently incensing about a group of people controlling so much wealth, profiting off the backs of the working classes, and never breaking a sweat, while the whole time being taxed at a lower percentage than they would if they earned their money the “honest” way.

At the same time, I find this idea of the universal income as you’ve proposed it equally upsetting. I certainly think the concept is worth exploring, because @Ron Beasley is right to point out that we are in a changing world in which the population grows while the number of workers needed shrinks. There just has to be a way that everyone works. To have any system where some work while others earn income for being a futuristic lower-leisure class certainly causes me to worry about the corrosive moral effects of just another form of inequality calling to mind the true nature of practiced communism.

There’s been a lot of criticism of Piketty’s analysis from other economics like Cowen and Mankiw. Surprised you didn’t mention any of it. Not everyone is enraptured by the book or its policy recommendations.

Yes, they’re good at getting hired as CEOs. There’s not really any evidence that they are good for the companies that hire them, or that any tangible successes you can point to are anything but a survivor effect. Sort of like stockbrokers.

The only plausible defense for a doubling of average executive compensation nationally would be a doubling of corporate profits nationally. Hint: this hasn’t happened. There is also no correlation between executive compensation and corporate profits. You’d think this would be a clue.

@superdestroyer: Where is this place, this Superdestroyerland, where corporations cannot cheat on their taxes? I would really like to see that place.

@superdestroyer: And while you are at it, kindly show me this “massive advantage” that mom and pop businesses have over giant multinational corporations.

That, again, would be worth a look.

Conservatives are not troubled by things like this, but $10.10 an hour for workers? Worse than communism! Worse than Hitler!

http://techcrunch.com/2014/04/16/fired-yahoo-coo-henrique-de-castros-severance-totaled-58m/

@ SD

I take it that you did not think about the crime level in public housing projects in urban areas of the U.S.

Umm. Look at the crime levels in pretty much any poor area, anywhere. Or, you could try to build a fact based case to support, something beyond “because I think so.”

You might want to look at crime in poor neighborhoods in America before welfare existed.

@anjin-san: It turns out that the reporting on de Castro is rather inflammatory. He got what he was owed as a condition of hiring:

He would have gotten that money after a year had he continued on in the job.

Is the amount outrageous? Possibly. But Meyer really wanted to lure him away from Google, where he was also apparently making a ton of money as their top sales guy. He was being asked to leave one of the most successful and prestigious companies on the planet for a dinosaur company under new management. That he wound up being a bad fit with the culture Meyer was trying to establish is hardly his fault.

@Hal_10000: Mankiw is not worth the time to read as his criticisms amount to a series of normative statements. This is, after all, the man who said that it is rational for executives to loot their companies. Cowen’s response is more interesting but his anti-worker bigotry tends to interfere. The best review I’ve read comes from Jamie Galbraith who identifies two significant problems with Piketty’s work:

1) Piketty pretends the Cambridge capital controversies never happened (as does the entire neoclassical school) by assuming all forms of capital are the same and provide the same returns and can therefore be lumped together in aggregate.

2) Piketty’s solution, a global wealth tax, would therefore be very difficult to levy (much more so than an income tax) and enforce, besides the virtual impossibility of getting every country to legislate it. The broad nature of capital would inevitably result in various exemptions and deductions that quickly undermine the intent of the tax.

@anjin-san:

For years CEO have been saying that high salaries and compensation packages are justified based on the performance of the company, yet again and again we see that these people are rewarded with exorbitant severance packages after they run the company into the ditch. It’s quite apparent that high-level compensation is often not related at all to (or correlated with) overall company performance.

Performance-based compensation is for regular line workers or middle-management. In the stratosphere of upper management, performance-based pay is a no-lose proposition – you’re very well compensated during periods of strong company performance, and if company performance is far less than stellar (perhaps poor) you’re still handsomely compensated as you’re shown the door.

Since the 1980s we’ve gone through 3 successive periods of strong economic growth and it is quite clear that a disproportionate share of the wealth created during the past 30 years has accrued to the most elite people in the country. Statistics consistently show that income growth for middle class workers has been sluggish at best.

So what is it? Is it that when companies are successful, it is because only senior management is productive? Or is that when companies are not performing well, only non-management employees are to blame? For the past few years the answer is “It is both.” This ‘compensation game’ is one that senior management cannot lose.

@al-Ameda: Again, as noted in my previous comment on this, those were the terms of his being lured away from Google. This isn’t a golden parachute–it’s essentially a delayed signing bonus.

@ James Joyner

Did I say it was? I blame Meyer, as well as the general culture that says senior executives should reap vast riches regardless of performance. Blowing that much money on an executive that failed should put her job in jeopardy.

@ James Joyner

And you know this – how exactly? Were you spending time on their executive suite?

A senior executive at this level is not able to assess the culture of a perspective employer and determine if it something that will work for him? He does not have an obligation to make the fit work at these compensation levels? Guess not, the game was rigged so that he wins big either way. Must be nice.

Now lets talk about those greedy workers at Wal-Mart who have the temerity to want to be paid enough to live on.

@al-Ameda: To my knowledge the only correlations found between executive pay and performance have been negative, suggesting exceedingly high pay actually results in worse outcomes.

@James Joyner:

I get that, but I don’t see how it extenuates anything in this context. It’s still exorbitant pay for crap performance. The fact that it was promised up front makes this even more egregious; there was never any chance that de Castro could be held accountable for his performance.

@DrDaveT: Oh, I don’t dispute that. It struck me that the vitriol was being directed at de Castro, who simply negotiated the best deal he could get for leaving Google for a struggling Yahoo, rather than at Meyer, who agreed to the terms.

@anjin-san: I think the burden is on Meyer. She lured him away from Google and should have known what she was getting. I have no opinion on his virtues as an employee, having never heard of him before this morning. But he’s not someone applying for a minimum wage job at Walmart; he was a senior executive at Google being recruited for a job elsewhere. That puts him in a vastly superior negotiating position.

@ James Joyner

Especially when the corporate culture of the 21st century says that it is perfectly acceptable for executive to loot their own companies.

I’m looking forward to the next generic press release from Yahoo when layoffs come around – “It’s regrettable, but we need to tighten our belts.”