A Quote to Ponder (Partisanship and Governance Edition)

A bit of musing on parties, elections, and governance,

The discussion that I was getting at in my post this morning (as well as my general attitude towards our government, its institutions, and the parties that vie to control them) made me think of the following quotation by mathematician Henry Droop:

As every representative is elected to represent one of these two parties, the nation, as represented in the assembly, appears to consist only of these two parties, each bent on carrying out its own programme. But, in fact, a large proportion of the electors who vote for the candidates of the one party or the other really care much more about the country being honestly and wisely governed than about the particular points at issue between the two parties; and if this moderate non-partisan section of the electors had their separate representatives in the assembly, they would be able to mediate between the opposing parties and prevent the one party from pushing their advantage too far, and the other from prolonging a factious opposition. With majority voting they can only intervene at general elections, and even then cannot punish one party for excessive partisanship, without giving a lease of uncontrolled power to their rivals.

Speaking for myself, I clearly moved out of a partisan identity some time ago into the realm of one who “care[s] much more about the country being honestly and wisely governed than about the particular points at issue between the two parties.” Not, by the way, that I don’t have various opinions on those points at issue. As such, my frustration with Republicans especially (as readers will, no doubt have noticed in recent years) has been based in the fact that I am utterly unconvinced of their general interest in governance. The Hagel nomination is a recent good example of this. On a larger scale, I would throw in: the ridiculous debt ceiling debate, the creation of the Fiscal Cliff, as well as the sequester.

More generically (or, perhaps, more philosophically), the binary choices we have in our elections is increasingly maddening to me, because at the end of the day there are only two viable choices (although, yes, there are third party options as well). Now, in some contests, an obvious better candidate is on the ballot, and one can cast a positive vote in that direction. However, more likely than not, one has to decide to double down on a team, or to vote to punish the party that one find the most in need of punishing (I suppose those two choices are not mutually exclusive). One can also opt to go third party and either be a) hoping to build for the future, or b) simply acknowledge that one is casting a protest vote. While in many ways I am all for option “a” the truth is that the structure of our electoral system means that “b” is reality for the foreseeable future (party system change in our system comes, I am increasing convinced, via primaries, not third party challenges, and hence the long-term solidification of strict bipartism in the US).

And yes: I am down on our national institutions today in my writings, and in my thinking for a while now, because they are not producing the results we think that they are (e.g., competitive, democratic outcomes that reflect public sentiments, even if filtered through federalism*). I do not expect any of it to change, by the way, but am utterly convinced that we (all of us) need to understand, for good or ill (and opinions will vary) as to effects of our institutions on our politics. I am, of course, swimming well upstream here, as the general popular discourse runs in the direction of the Framers as demigods who created near perfection.

Source of the above: a page over at Matthew Shugart’s blog, Fruits and Votes (which has more info on Droop, if one is so inclined).

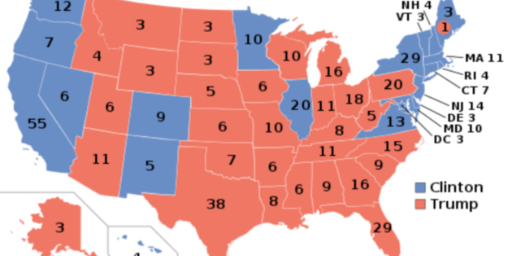

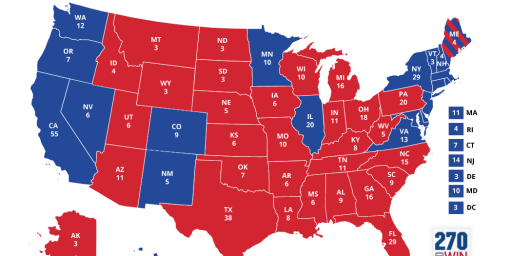

*That is, lest the charge be made, I am not assuming anyone thinks we are going to have, or currently have, pure majority rule. Still, when one party can get more votes nationally, and still not control the legislature, this is a problem of representation, especially when so many districts are non-competitive and the Senate is also construed in a way that not only guarantees there can be no national majority rule (because all states are co-equal) but also because of the filibuster.

It would be nice if a millionaire would fund a small-i independent for President.

(Not that money matters, eh James?)

(A Doctor Evil moment … “billionaire” of course.)

Look up Mixed-member proportional representation. Many people think proportional representation can only be done without local representatives, but this is an elegant system to have both. It also drastically weakens the power of gerrymandering.

I swear I’m going to try not to nitpick you on this as I sometimes do… but could you explain how the senate “guarantees there can be no national rule (because all states are co-equal)”? I can see how the co-equal representation means that a minority rule is possible, but it doesn’t foreclose the possibility of a national majority rule depending on the results at any given time. Right now, we have a Democratic senate majority and a Democratic-supporting voting majority, for instance.

(We are in perfect agreement about the problems of the House results, however.)

@john personna: Actually, we had that once before with Perot–no go.

More to the point: the structure of the electoral process, both for president and for congress, makes a third party win a mathematical difficulty. In any given congressional district, such a party would have to beat both the Rs and Ds to win a seat.

@Tran: I would very much like to see MMP in the US, yes.

@Trumwill: Perhaps I am misunderstanding, but unified government does not equal perfect majoritarian rule.

My point is this: due to the way the Senate is constructed, and given the distribution of the population across the 50 states, it is quite easy, if not likely, that a given majority in the Senate does not represent the majority of the population, regardless of the partisan makeup of the chamber. At a minimum, since the 9 largest states have roughly half the population, any attempt by the large states to control the small ones would be routed by the other states.

Now you are right: it is possible for the Senate to be run by a 51 senators who represent more than half the country–although the partisan makeup of those states make such a coalition unlikely.

Further, the odds that the House and Senate would be represent the exact same 51% of the population is quite low, if not impossible.

As such, the pure majority rule that so many fear is quite difficult, if not impossible, to achieve in the US.

(There is also the fact that since the House represents different constituencies than does the Senate, that a convergence of a true, 51% majority dominating the whole Congress is all but impossible to achieve).,

Sadly, saying we have even two choices is overly generous. Our options are limited to what The Funders (in Lawrence Lessig’s terms) will allow, so we get one choice that comes in two nominally different varieties. All complaints about partisans and institutions is missing the big picture.

I expect you’re familiar with this, Steven, but I’ll rcommend the book to others. Hacker and Pierson in Winner Take All Politics talk about “drift”. The idea is that, as Steven notes, our system provides numerous opportunities to stop anything new. This makes our system inherently conservative. Those who currently have wealth and power can readily defend the status quo.

However, I’ll note that this “institutional” issue didn’t seem to be a big problem until the Republican Party went seriously off the rails to the right. I’ll second a fear that without a credible Republican counterweight, eventually the Democrats will become entrenched and corrupt. However, in the near term, we seem to have a clear choice between a centrist party making some reasonable effort to govern and an extreme right party that is not.

@Steven L. Taylor: Okay, I misunderstood your statement (which is what I figured happened). You’re right that it can take significantly more than 50% of popular opinion (or congressional control) to have such a majority to enact change.

(Whether this is a good thing or a bad thing, though, is a subjective matter.)