Are Special Forces Special Enough?

US Army Special Forces are the best we have at working with far-flung villagers. Are they good enough?

In a World Politics Review column titled, “Special Forces, or the Danger of Even a Lot of Knowledge,” former Army Ranger and current Middle East policy expert Andrew Exum argues persuasively that special operations forces have far less regional and cultural knowledge than they’re given credit for. This is important, Exum explains, because it’s easy to assume that a crash course in the local language and mores combined with some time in country allow people to make more nuanced judgments than they’re truly qualified to make.

Driving his point home, though, I believe Exum takes it too far:

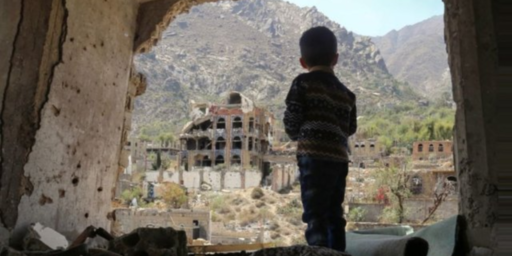

The more time an outsider spends in a complex environment like Yemen, though, the more he or she is humble about what he or she can know. The best Yemen analysts I know — men and women who have spent years in the country and additional years spent learning Arabic — are among the most cautious when it comes to proclamations about the country’s people, tribes and politics. So when special operations commanders assure me their subordinate commanders, who might not speak Arabic fluently and most likely have not spent years in the country, really get a place like Yemen, I get nervous.

After I left the U.S. Army in 2004, I moved to Lebanon, where I spent most of the next five years earning a master’s degree from the American University of Beirut, studying Arabic and doing the bulk of the field work for my doctoral dissertation on Hezbollah and the fighting in southern Lebanon during the 1990s. To this day, the more time I spend in Lebanon — and the more I get to know the real experts on the country — the less confident I grow in my own ability to “know” Lebanese politics, peoples and norms.

Each semester, I teach a block of instruction on insurgency and counterinsurgency in Afghanistan to U.S. military officers who, having volunteered to serve in Afghanistan and Pakistan as part of the “Af-Pak Hands” program, are learning Urdu, Dari and Pashto. And I always conclude with a warning: If these soldiers had been immersed in two years of intensive language training and an additional four years of education in the people, tribes, history and cultures of Afghanistan, at the end of those six years, they would still have only a fraction of the local knowledge of an illiterate subsistence farmer native to the region. [emphasis mine]

Having spent years teaching the basics of American politics to relatively bright American college freshmen, I’m highly dubious of this assertion. Despite having spent eighteen years living in America, twelve of them in the American school system, very few of these students had even a basic understanding of how our system worked before the class began. They had similar deficits about American history, US political economy, or American cultural norms outside of their local niche group. And these people were all functionally literate and well above the 50th percentile in intellectual capability.

The fact of the matter is that most people–even most intelligent and literate people–pay very little attention to larger issues of politics, economics, and culture. They simply have no interest in these things and don’t bother to ask even basic questions about them.

Ex is probably right that the illiterate Afghan farmer will have more “local knowledge” if one defines “local” in the narrowest of terms. He’ll have relationships with and more intimate familiarity with others in the tribe or village than some newbie Green Beret. He’ll even have more command of the local dialects and idiom. But that young special operator will almost surely be more knowledgeable about the issues related to local government and economics even at the provincial level, much less in relation to Afghanistan or the region as a whole. If the mission is building an effective central government and security infrastructure, that knowledge is quite important.

But is it enough? Ex argues otherwise:

For the purposes of illustration, let us consider Yemen, where the U.S. military is today waging war both directly against militant groups associated with al-Qaida as well as indirectly through the security forces of the Yemeni government. As part of that effort, U.S. Special Forces “A teams” teach, train and mentor soldiers and units within the Yemeni military, and I have heard U.S. special operations commanders express confidence that U.S. Special Forces officers “get” the country’s tribal and political dynamics. These commanders have faith that their young A-team leaders can intelligently navigate the minefield that is local Yemeni politics in a way that secures U.S. interests without distorting local balances of power or incentive structures. Even when a team leader is particularly callow, they assure me, more-experienced team sergeants and warrant officers stand close by ready to assist him.

I’m not sure that knowledge is the key ingredient here so much as relationships and the trust that comes with them. Someone with extensive cultural and linguistic training could presumably pick up on the social dynamics in relatively short order. While there are some nuances unique to every situation, broad expertise can help provide a roadmap for navigating the minefields while feeling one’s way around.

Ultimately, though, Ex is essentially arguing that outside intervention in tribal conflicts is absurdly complex and perilous. We simply don’t have anyone more suited to these tasks than regionally specialized US Army Special Forces teams working with their counterparts in US Army Civil Affairs units and various ad hoc groupings of State Department personnel, Provincial Reconstruction Teams, and the like.

If they can’t do it, I don’t know who can. Most likely, the answer is: Nobody. Unless we’re prepared to spend decades learning the local culture and building trust with the tribal leaders–and even the investment of decades is no sure thing, as most Western colonial powers learned–it may simply be impossible to master the nuances and necessary to transform these societies.

Great article and analysis James. Totally agree with your overall point.

I did want to take issue with one section…

As the resident Anthropologist, I’m sure that is exactly what Ex means by “local knowledge” and I think you’re probably undervaluing it’s worth in these sorts of situations.

In fact, the work training that Ex is discussing actually exceedingly close to what anthropologist do to prepare for the field.* And what most of us find — upon reaching it — is that while we may command an excellent macro understanding of the region, most don’t have the micro understanding to take action. Part of the basis for the “farming cycle” mode of study is the assumption that you need to spend the first half of the year gaining that critical “local knowledge” (typically by making lots of mistakes).

The difference, and I agree that this is Ex’s point, is the notion that the Special Forces (or Anthropologists) can be immediately dropped into the field… which gets to:

Here’s where I disagree. If the job is to try and construct the high level infrastructure, then I think you are right. But if the goal is actually connecting that central, high level infrastructure to a local implementation, then its doomed to failure without deep local knowledge.

And that’s the problem with assuming that special forces (even those with the Macro book learning) can be dropped into the field and be immediately effective.

Personally, I have deep issues with “the farming cycle” — but even in my work with American Professionals (a group I came out of) it still amazes me how many mistakes I’ve made in my early phases of in the field research because I mistook my understanding of how macro practices were supposed to work for the way that those practices actually worked in the local.

* For Anthopologists, of course, half the point is to make those mistakes so we can learn from them. Unlike when Special Forces make mistakes, lives are rarely immediately on the line.

@mattb: Good feedback and insights.

My problem, though, is that this sets the bar beyond the level of our reach. Essentially, then, we need a few hundred thousand PhD anthropologists with regional expertise plus all of the military skills, training, and capabilities of Green Berets. That’s simply unachievable.

@James Joyner: Agree on both points.

As to setting the bar beyond the level of reach, it seems to me that has more to do with setting unrealistic expectations or time-lines. So, for example, I think that the public promises about how quick Iraq would rebound from the invasion are a good example of this. Ditto, some folks unrealistic expectations about Afghanistan.

I think we both agree that national building takes years (if not generations) for people born into the local knowledge. Expecting special forces to oversee huge advancements in the local level in months is setting them up for failure regardless of whether they have micro or macro training.

So the trick — one way above my pay grade — is to figure out how to let “the good,” or at the very least “the better”, not be the enemy of “the perfect” which is often what gets promised.

Beyond that, frankly, the pragmatist in me would like to see more engagement with Anthropologists, and to some degree that’s happened.

At the same time, the political leanings of my field as a whole tend to prevent those types of partnerships from taking place. Which means that the pool of talent the military gets to choose from is pretty limited and, sometimes IMHO, lacking. I’d like to see that change (and I can make arguments for why it should, with care, change a bit), but that isn’t in the cards in the foreseeable future.

Isn’t that what we have learned in Iraq and Afghanistan? That nobody can!

Yes, but the point of this exercise isn’t to turn special forces into academic historians. How much of the above is necessary to understand how Americans see the world, predict how they would react to things, and be able to collaborate with them effectively? Since, as you point out, most of them don’t know this information either, very little.

For the purposes of the special forces, knowing the fake version of a country’s history that most of the populace believes in is more important than knowing a country’s actual history.

@mattb: Fully agree and the military has gotten better at it. Frankly, State is more likely to draw anthropology types than DoD, so better mil-civilian cooperation along those lines is likely the way we’ll do it. But it’s incredibly hard to attract enough of the right kinds of people. And getting expectations in line with the mission is even harder.

@Ron Beasley: That’s my sense.

@James Joyner:

This makes sense too. If I had it all to do over again, and I’d gone anthro sooner, I would definitely have applied to the State Department.

Greetings:

When the time came for me to begin my world travels, my dear, now-departed father took me aside for another good bit of his advice. When you go to foreign countries, or even other parts of our own country, you go as a child. There is much to learn. Go gently. Eat the local food, laugh at the local jokes, and be very cautious with the local women.

I’m glad you posted on this, James. It sounds to me as though Andrew Exum is arguing that, if you want an army that’s capable of understanding the local language and the nuances of politics, culture, and mores, you’re necessarily in the colonizing business.

What do you call an army that goes in and spends enough time to garner the skills he’s outlined? An army of occupation.

The alternatives are to have an army that’s insufficiently prepared for effective COIN, an army that doesn’t engage in the kinds of “hearts and minds” activities implicitly involved and sees its core competencies as killing people and breaking their stuff, or a much greater reluctance to intervene than we have seen in recent decades.

@Dave Schuler:

And ironically that gets us back to the beginnings of Modern Anthropology in Europe, where early anthropologists were specifically working in the service of colonizing forces (and hence one modern Anthro’s problems with working with the military).

But regardless of how much immersion the Spec Ops receive, they will never be part of the culture and therefore can never really understand it. But deep understanding of the life of the common man isn’t their job. Their job is to be sensitive and open to the culture in order to win friends and influence people. The anthropologist sits back and ponders the imponderables. The Green Beret has a job to do, execute US policy, and has to enlist the local culture to accomplish his job. And, quite frankly, if he goes native, he’ll likely no longer be a useful operator for the US.

@JKB: Just to be clear, I AM NOT arguing for the “anthropologization” of the military. That would be a terrible idea.

Rather, I’m taking a position akin to what I read @JJ and @Dave Schuler doing — questioning what the function of our military should be.

Ultimately, the question is if you have a self defense/offensive force or a nation building/colonialization force.

The problem is that in the recent conflicts, the military has been tasked with being a national building force, in so much as you can implement a sustainable security infrastructure without doing some degree of nation building. And nation building requires a fundamentally different set of skills.

@James Joyner: No you don’t need Ph.D anthropologists and such. You need people who are willing to NOT speak in the theme of one of the teachers who gives a workshop at the school in Korea at which I teach:

“I’ve lived in Korea since 1992. I know everything that there is to know about Korea, Korean society, and teaching Korean children.”

Part of the problem of the pseudo-intellectual culture that has grown up around professional academics, think tank scholars, and managing editors of entities such at Atlantic Council is that you suffer from the same arrogance that you sometimes (rightly) criticize theological persons of–the inability to answer a serious question “I don’t know.” It is ok not to know the correct answer to a question sometimes. Even better if you are willing to be humble enough to acknowledge it and go to someone with no formal education who might know the answer.

Interestingly enough, the fellow teacher above constantly complains about how difficult it is to teach the students he has–at least when he is not giving lectures about how he knows everything there is to know about Korean culture.

@Just ‘nutha ig’rant cracker:

Perhaps I run in the wrong pseudo-intellectual crowd, but I actually her a lot of ‘I don’t knows.’ That may be the pervue of academics, where you have the space to research and an entirely different sort of time scale for answering questions.

I actually think the fear of not knowing problem is far more prevalent with pundits and professional consultants — those folks who build their livelihood on always, immediately having THE answer.

@mattb:

Exactly right!

@Just ‘nutha ig’rant cracker: @mattb: Yeah, the academics and think tankers I know–and I know a lot of them–say “I don’t know” all the time. The essence of expertise, in fact, is knowing what you don’t know. And the more you know the more you know you don’t know.

@mattb: First off, exccellent topic and discussion in the article and comments. I would like to comment on this theme of anthropologist v. SF v. civilian (state dept). I am a card carrying member of the American Anthropological Association (never made it to PhD, but maybe on day), cavalry officer who deployed a cav platoon to rural iraq, and on the civilian side have done tours through DHS and State HQs as a policy wonk.

The State Dept is no more prepared to deal with the realities on the ground than DOD. I say that unequivocally because State is 1. Small 2. Policy/diplomacy focused. Neither of those features give any micro-level insights into anything in particular. Many in the Foreign Service and civil service are expert political operators, but they are not so selected (so its hit or miss), and they function within the highly structured world of international relations and protocol. Their main value, in my experience, is as advisors to the operational world. What we can learn from them in DOD is the extreme importance of personal relationships. At every level, these folks operate in the background on the interpersonal level with their counterparts in other countries. “My esteemed colleague from Otherlandia” in one context is “Joseph who tells me about his kids” in another. The two-faced world of personal influence in the context of policies one doesn’t make but simply executes is the art of diplomacy. But remember, they function in a structured environment. From experience, getting a Statie to agree to an aggressive tactic or a cordon operation is a challenge. Their world gets as narrow as any infantry officer’s dreaming of the Fulda Gap once the structure of protocol melts.

The other thing I would like to draw attention to is a WWII debate about the value of Civil Affairs. CIVIL AFFAIRS:

SOLDIERS BECOME GOVERNORS is a Army publication that has some excellent insight, including this from Chapter 1:

“It is extremely unfortunate that the qualifications necessary for a civil administration are not developed among officers in times of peace. The history of the United States offers an uninterrupted series of wars, which demanded as their aftermath, the exercise by its officers of civil governmental functions. Despite the precedents of military governments in Mexico, California, the Southern States, Cuba, Porto Rico, Panama, China, the Philippines and elsewhere, the lesson has seemingly not been learned.”

That quote is from a report on occupation of Germany post WWI, written in 1920.

To close the circle on all this with SF. SOF in general seems to be filled with 3 types of operators: door breakers/enablers (SEALS, Rangers, CCT), collectors, and infiltrators (traditional SF insurgency role). SOF’s successes in conducting Counterterrorism in Iraq in parallel with GPF COIN (not so successful, IMHO) seems to me the real SOF success story. Not some mythical ability to act as the “statesman/Soldier”. The sad fact that SOF now bills itself as that will inevitably lead to multiple scenarios (I can think of a number) that should be avoided. In discussing SOF roles in occupation scenarios, both Exum’s and your (Joyner) articles overlook the simple fact that there is no precedent, no theory, and no operationally practical model for such a role; especially when GPF are present in theater (McChrystal’s story is one anecdote to prove the point).

Much more to say on this, but quite honestly, our main problem is a painfully uneducated officer corps. My PL tour in Iraq became comfortable once I realized I had enough usable personal relationships with the Sheikhs and the Iraqi Army officers to function effectively for my mission. I happened to be 27 by that point and would have functioned very differently as a 21yr old PL. Those CO Commanders and above are the weak spot that needs addressing, not capabilities and enablers.

@James Joyner: Glad to hear it isn’t just the folks I hang out with (both on and offline). ;P

What makes the Army Special Forces so special isn’t their expertise in any one area but the ability to adapt and adapt quickly in many different areas. They often do what many consider impossible. That doesn’t mean they can do everything that is impossible.

The above article addresses mainly Foreign Internal Defense (FID), which is only one of the many primary missions they have. However,let us stick with that area. Yes it would be nice to have thorough understanding of local, national (U.S. and other nations that are involved), and world cultures and needs. However those people don’t exist. There are those who have a wider knowledge in those areas. However, anyone who thinks they know everything even on their local culture and people are fooling themselves.

So as James said, you send in the best that you have. That job often falls to the Army SF. Do they know everything about a culture when they go in? NO. However, they try to know enough so they can adapt enough to accomplish their mission. They use their personal interaction, intelligence, and knowledge to help them. They have had some failures but many successes as well. Sometimes a FID or UW mission will take decades to accomplish and never will be acknowledge. It usually is a long process and there is a natural process to things. Unfortunately, the MSM and American public are not patient. That is why the DOD will often try to keep these missions out of the headlines. Not to cover things up but to allow enough time for the process to proceed the way it should. Politicians, MSM, public get wind of it and they get inpatient, which usually results in brash moves that results in failed missions.

Besides what many may believe, the mission often isn’t to transform a culture to look exactly like ours. Also understanding a culture may help in its transformation, but a complete understandingof it is not necessary and sometimes it is even detrimental.

@Wayne: “It usually is a long process and there is a natural process to things. Unfortunately, the MSM and American public are not patient. That is why the DOD will often try to keep these missions out of the headlines. Not to cover things up but to allow enough time for the process to proceed the way it should. Politicians, MSM, public get wind of it and they get inpatient, which usually results in brash moves that results in failed missions. ”

Probably the greatest advantage of (relatively) small SF missions is that they can last for a decade, with minimal strain on resources.

@Wayne: Finally, someone who actually knows what they are talking about vis a vis “Special Forces” vs “SOF” writ large! Thank you Wayne. I thought for a moment i was going crazy.

@Wayne: First of all, if your the usual Wayne, thank you so much for this great analysis. HUGE LIKE! Please keep sharing these sorts of really well thought out and informative posts!

This needs to be constantly repeated! I think the biggest problem is that civilian officials and pundits, from both sides of the aisle, often help propagate this mistaken view.

Thanks for a very informative read. As one of those Special Forces Operators who worked in South and Central America, Europe and Africa I can categoricllly state that our persoonel do not think or believe that we are the “tell all, know all” on foreign affairs. We are very clear that we are a small part of a US mission and policy that begins and ends with our President and his administration. As military we are prepared to serve and execute the orders and directives of the President and all those appointed. Our US system of checks and balances insures that we never step outside the box of what the overall approved strategy is. We are very proficient at many things one of those is listening and reporting to higher. In addition to that is, our powers of observation are powerful to see first hand what is occurring where we are. When not in a true combat role we still have the same reporting requirements to our higher who then send the information up to where it needs to go. The preparation and understandiing of what is required and is at stake is evident in the decades of success our Quiet Professionalls have had as part of the Country Teams where we serve. Let that term be clear; We serve. We serve our nation, we serve those we are working with and for and we serve each other. We never percieve we are the answer to the issue at hand if not a part of an overall solution. Additionally our Warriors are flexible. As foreign policy changes, so may our mission and we are always prepared. Foreign policy is an ever chaging dynamic that rquires very dynamic and Special personnel to manage and execute. In my opinion, our nation has the very best we can offer when we send United States Special Operators. De Oppresso Liber/RLTW

@Wayne: No one in their right mind would try to replace operators in their specialty missions like FID etc. It seems the confusion stems from a failure to recognize that a S. American FID mission isn’t the OIF/OEF full force occupation. This is where the SOCOM mission reaches its natural limit. At the risk of sounding pedantic, that is the distinction between GENERAL and SPECIAL operations.

Exum’s article is itself confused in this distinction. When doing FID (a real SOF mission that requires long-term cultural contact), the classic approach of those forces was sufficient to have trained and able personel perform the mission. OIF/OEF are not, by definition, description, fact, and history, FID missions. They are occupations, which carry fundamentaly different standards. The federal and public fetish for things SOCOM is more detrimental to the quality and SPECIALization of those forces than any operational environment.

The general purpose forces are not there to storm the Fulda Gap. They do everything else that isn’t special. That means pitched battles, sieges, amphibious assaults, siezure of territory, control of 3D environments, and the beast of them all, occupation. No matter how high speed SOF are, if the GPF are not up to par then the interests of the state cannot be adequately secured.

We need get off the SOCOM cheerleader bandwagon and realize that the universe hasn’t changed that much. SOF shouldn’t lead or command occupations for the same reason that GPF should lead or command FID (by definition not in an occupation environment).

@Sparapet: Wow… Thanks so much for the comments… There’s a lot of stuff in there that I need to think about…

Woot! I’m not sure I can recommend the PhD route (my own current slog), but its great to hear that AAA members are serving and using their skills pragmatically. Many of my favorite students so far have been the older ROTC kids (‘specially the Jarheads) who I’ve often found to be the most observant and offer the best, respectful push back.

This attention to “personal relationships” — I think — ties many of the of the key aspects of this thread together. Those relationships grow out of the development of local knoweldge and can never appear over night. To @Wayne‘s point about timing, developing the network to ensure successful action takes a lot of time (not to mention a more “mature” outlook).

Of course, that shouldn’t be taken as an argument for SoF (I’m such a poser trying to use the language) majoring in how to make friends and influence people.

I think all of the arguments are more or less fleshed out here, but I will reiterate something I wrote yesterday, and that is about shaping the operational environment. Exum’s argument about direct action (DA) versus “indirect” in the role that special forces plays is supremely short sighted. U.S. Army Special Forces operate along the entire spectrum of conflict. Their expertise is not their regional focus, but their ability to change their disposition from moment to moment as a conflict metamorphoses from one place along the spectrum and back again, and to manage the myriad of tasks that require different postures and different hats. From day to day, moment to moment an SFODA may be adapting from a security assistance engagement into a civil war and may be required to move from being an arbiter of cooperation to directly engaging in a gun battle to ending the day treating sick villagers. Dr. Joyner is correct about managing expectations, and all of the commentators are correct about some limitations in training and employment, but no diplomat, no anthropologist or aid worker or Ranger is going to be prepared to flip the switch between each setting and temper their action in the context of the overall operational environment.

It is intellectually lazy to shrink away from this objective because it is difficult and because the prevailing ideological mindset is that this is not a role for the U.S. We are not able to pull back from our position diffusing, preventing and resolving international armed conflict. Ian Bremmer recently discussed this in an interview with the 7 Revolutions Project at CSIS. I am certain the U.S. is not ready to cede to China’s “arbitrage of differentials” on economics and security because we are not prepared to use the full spectrum of state sanctioned violence to ensure stability and order. I recommend reading his thoughts on this or checking out his new book. Exum et al should consider that quite a few countries still depend on America’s global leadership.