Are the Teachers Quitting?

The plural of anecdote is not data.

We’ve seen a lot of reports over the last few months about a mass exodus from the classroom prompted by the COVID pandemic.

- Guardian, “‘Exhausted and underpaid’: teachers across the US are leaving their jobs in numbers,” Oct. 4, 2021.

- CBS, “Teacher shortages — made worse by COVID-19 — shutter schools across U.S.,” Nov. 12, 2021.

- Axios, “COVID pushes teachers to pivot careers,” Feb. 7, 2022.

- Bloomberg, “More Teachers Than Ever Are Considering Leaving the Profession,” Jan. 6, 2022.

- US News, “Half of Teachers Say They’re Thinking About Quitting, But Will They?” Feb. 3, 2022.

It stands to reason, right? Teaching is a stressful job. That pay is mediocre. There’s increasing bureaucracy and decreasing respect. And COVID has made it all worse, with the prospect of getting sick, the stresses remote teaching, masking, and parental anger.

And, yet, Kevin Drum looks at the BLS data and finds no evidence anything unusual is going on.

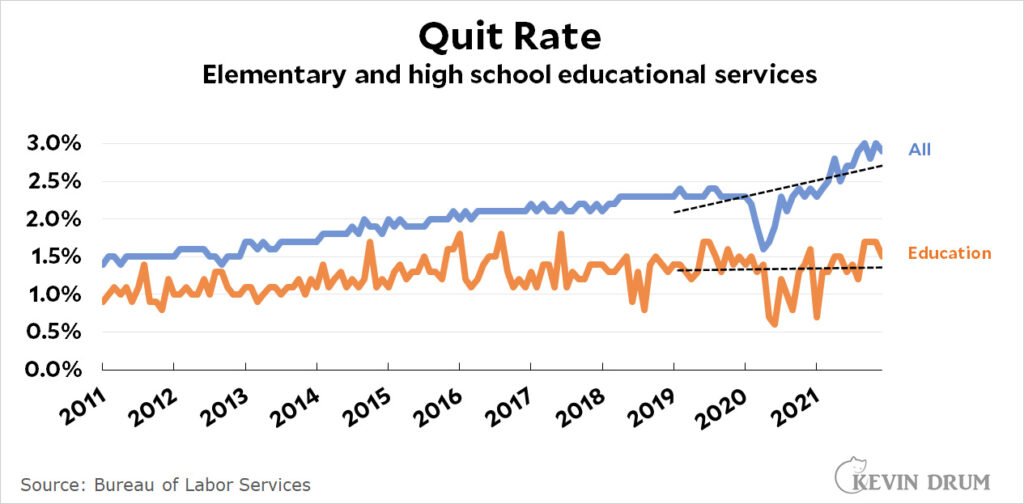

The trendline above the blue data shows quits for all workers since the year before the pandemic. The orange line does the same for education workers. As you can see—in mere seconds!—the top line has been trending sharply upward since 2020. Education workers, however, aren’t quitting in high numbers. Their trendline is dead flat.

Now, “educational services” includes principals, teachers, and teacher assistants. Teachers make up about two-thirds of that. So it’s possible that teachers really are quitting in huge numbers, but principals and teacher assistants are sitting tight and bringing the quit average down. Anything is possible. But I wouldn’t put much stock in that particular possibility.

But maybe retirements are up? Nope. That’s included under “other,” and it’s too small to even show up on the chart.

FiveThirtyEight’s Rebecca Klein found the same thing when she looked into the issue last November:

Throughout the past year, surveys and polls have pointed to an oncoming crisis in education: a mass exodus of unhappy K-12 teachers. Surveys from unions and education-research groups have warned that anywhere from one-fourth to more than half of U.S. educators were considering a career change.

Except that doesn’t seem to have happened. The most recent statistics, though still limited, suggest that while some districts are reporting significant faculty shortages, the country overall is not facing a sudden teacher shortage. Any staffing shortages for full-time K-12 teachers appear far less severe and widespread than those for support staff like substitute teachers, bus drivers and paraprofessionals, who are paid less and encounter more job instability.

In a female-dominated profession, these numbers notably contrast trends showing that women in particular have been leaving their jobs at high rates throughout COVID-19. While labor-force participation for women dropped significantly at the start of the pandemic, and still remains about 2 percentage points below pre-pandemic levels, teachers by and large seem to be staying at their jobs.

So, why have the doomsday scenarios not come true? There are many explanations — and the ways they overlap tell us something about the state of American schools, the inner workings of America’s economy and the way gender shapes the American workforce.

[…]

In an EdWeek Research Center report released in October, a significant number of district leaders and principals surveyed — a little less than half — said that their district had struggled to hire a sufficient number of full-time teachers. This number paled in comparison, though, with the nearly 80 percent of school leaders who said they were struggling to find substitute teachers, the nearly 70 percent who said they were struggling to find bus drivers and the 55 percent who said they were struggling to find paraprofessionals.

More concrete jobs data suggests that school employees have largely stayed put. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, fewer public-education professionals quit their jobs between the months of April and August the past two years than did so during that same time immediately before the pandemic. In 2019, around 470,000 public-education employees quit their jobs between April and August compared with around 285,000 in the same period in 2020 and around 300,000 in 2021. Notably, this data includes both full-time teachers, support staff and higher-education employees, though teachers make up a majority of those included, says Chad Aldeman, policy director of Edunomics Lab, an education-policy research center, at Georgetown University.

Experts point to multiple reasons for this trend. While women have been disproportionately affected by mass COVID-related job losses, teachers haven’t faced the types of widespread layoffs experienced by workers in other professions — including other types of public school employees like bus drivers. Moreover, relative to other types of jobs disproportionately held by women, teachers have more job stability and receive more generous benefits. Educators often get into their work for specifically mission-driven purposes, too, making them uniquely positioned to decide to stay at their jobs, even during particularly stressful periods, experts say.

[…]

Vacancies have increased, suggesting that districts might be beefing up hiring after a year of uncertainty and an influx in federal aid. In other words, labor shortages are not totally attributable to increased turnover. And while early data on teacher retirements suggests that there might have been increases on the margins in some places, fears of mass retirements have not borne out so far.

The fact that so many more teachers report that they’re considering leaving the profession and an overall economy that’s looking for workers may well mean that a mass exodus happens in the near future. But it hasn’t happened yet.

In a recent blog post, Chad Aldeman, policy director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, stresses that the fact teachers haven’t run screaming out the door in mass numbers

doesn’t mean there are no labor challenges in K-12. It’s just that those issues are smaller in magnitude than what the private sector faces, and they are much more about specific schools and particular roles within schools. Districts should respond accordingly with solutions tailored to the actual challenges schools face.

K-12 districts are reporting a higher number of vacancies compared with historical norms. In a typical year, a school district with 1,000 employees might have about 10 to 15 job openings in January. But this year, the number is on track to be twice as high. Still, a high vacancy rate does not necessarily mean people are quitting at higher rates. Instead, the elevated job openings are caused by a mix of factors, including a desire to staff back up after employment reductions last year, an influx of state and federal money allowing districts to spend freely and a tight labor market fueled by lingering COVID fears and stiff competition from other industries.

[…]

[D]istricts were facing disproportionately large challenges in filling special education, English learner and STEM jobs. For example, relative to the number of positions overall, there were eight times as many job openings for special education teachers as general elementary teachers. These disparities were worse in high-poverty and rural districts. It’s tempting to group all these issues together as one labor shortage, but districts can’t respond to these discrete challenges with universal solutions.

Which seems to push back against one explanation Drum offers, in the comments section of his post, namely that “teachers in NYC are quitting in high numbers, and that makes news since most of the big media outlets are in NYC.”

I suspect there have been some “excess” retirements due to the pandemic. I’m not sure how you’d measure that. It would need to be related to the median ages of the teachers in various districts.

Also, who is retiring or otherwise leaving teaching is important as well. Teachers are people not commodities. There’s a 90% rule in anything dealing with people that doesn’t apply to widgets.

Changing careers is difficult and most often, expensive, you will likely take a significant pay cut. A teacher considering/desiring to leave faces those challenges and giving up a benefits package that may not be matched in the private sector. Outside of large urban areas, teaching can be one of the better paying careers available, which also contributes to teachers staying put.

@Sleeping Dog:

Including health care – and this is not exclusive to teachers either.

Libertarian blathering about a frictionless market outside of politics have always and will always be entirely strawman fallacy misdirect nonsense. Markets are actively constrained by politics.. both laws made by local/state/national legislatures and judicial decisions.

Why is the only healthcare available after you resign a job the super-expensive COBRA? Politics. Why is healthcare only available via employers? Politics. Excuse me, “affordable.”

Why is healthcare bankruptcy only a thing in the US? Yep, politics.

Pulling back to the original question.. Is the true goal of policies surrounding any one specific job/career -in this thread’s case, teaching- to remove all the barriers to people choosing to take the risk of leaving the relative security of that job to Create A Business.. or to keep people doing jobs they don’t like at pay they don’t like? I’m pretty sure I know the answer!

I have a lot of friends who are teachers, and only know of one who wants to quit. Her situation is not great–she and her husband both have complex medical conditions that her health insurance–even as a teacher–is barely able to handle. Teaching is also fairly complicated to transition to another career from, unless you do some side training (she’s an elementary school teacher so most of the direct/most logical jobs are in child care, which manages to pay even less with much worse benefits).

So, she’s essentially trapped in her job for the medical benefits, and because of her medical conditions she’s at risk for severe covid despite being vaxxed and boosted. She’s in a red state that is anti-masks, especially for children, so there’s really no upside. I fear more for her mental state than her physical one at this point, it’s been multiple years of living at stress levels that are astronomical.

There is always high turnover in teaching. Estimates vary but a rule of thumb is that 50% of new teachers quit within the first 5 years. So there is a continuous pipeline of new teachers into the system. The articles all talked about demand but didn’t address anything about supply. What supply are the schools of education pumping out? How many people in other careers are transitioning into teaching?

There is a real issue with getting subs. One, they are not paid much. Two, they tend to be older (and less likely to want to go into a classroom of little disease vectors). Three, the various COVID surges effect everybody, regular teachers and subs alike so the demand for subs coincide with the shrinkage of the sub pool.

In our districts, mid January, the demand for subs, far outstripped the supply. Everybody in the district was subject to being recruited to sub, including folks in HR, finance, transportation. My wife, an elementary school counselor, had to put her regular job aside several times just to be the teacher of a classroom. At least she was an experienced teacher.

That all said, there is a lot of pressure on teachers right now, from being required to be vaccinated, from an increase in really needy children who bring their less than desirable home life to school (I’m being kind here) to parents who, quite frankly, need the schools to be their daycare so they can work.

It’s going to take time to settle down.

People who want to leave in good graces have to play by specific rules. In order to maintain retirement eligibility, you may have to provide notice more than one school year in advance. In order to keep your license, you may need to work out your contract. And in most states, the retirement plans are statewide, so you can’t just up and leave one district for a better job in another district without planning ahead.

So there are potential lags between when the person decides to leave and when they actually can leave unless they want to just say “f- it.”

There are also structural reasons that disincentivize teachers quitting, related to future benefits and the seniority system. Because of these, teachers who quit can suffer a large opportunity cost and they can sometimes lose seniority even if they quit and come back into teaching. In some ways, it’s similar to military personnel who are incentivized to stick around until 20 years when it’s clear many would rather leave earlier.

Given the lack of respect and the crappy pay…I’d quit too.

Have you seen the crap they are facing in the Red States?

It’s ridiculous.

It’s the middle of the school year. Check-in after June.

All of the above–original post and comments alike–are in the mix. It’s the dead of winter. Usually, I work one or two days a week. Last year and this (so far)? I’ve worked almost every day school has been in session since New Year’s Day. And I only work high school and only 2 buildings at that. So yeah. There’s definitely a substitute teacher shortage.

I live in Washington, so our salaries are pretty good–not living in Seattle good (or even buying a house in Kelso, WA, good) but above average–if only slightly–last time I checked. Attrition in the first five years is still the big driver of the pseudo crisis just as it was in 1986 when I went back to get my certificate. In my districts, the administrators measure the “crisis” by how easy it is to attract experienced teachers to the districts. By that measure, the crisis is pretty extreme in that most of the hires these days are newbies. I suspect that MSM coverage evolves from “what would the society do if…” issues. And the problem of no longer being able to process the students through the mill in 12 years because we’ve spent two or three with high absence levels because of Covid-19.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl: Have you seen the crap they are facing in the Red States?

It’s ridiculous.

Have you seen the crap they are facing in the Blue States? It’s ridiculous.

@John430: Yay, you learned to copy and paste! What’s next, potty training?