Feds Make 32 Percent Less than Private Sector Counterparts (Or 17 Percent More)

Dueling data on civil service compensation belie the adage that you can't choose your own facts.

Dueling data on civil service compensation belie the adage that you can’t choose your own facts.

Government Executive (“Feds Make 32 Percent Less than Private Sector Counterparts, Salary Council Says“):

Federal employees on average earn 31.86 percent less than their counterparts in non-federal jobs, said an advisory council on compensation issues Tuesday.

The Federal Salary Council, a group of compensation experts and union officials that issues recommendations to the Presidential Pay Agent, made the determination based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The new figure is slightly smaller than the council’s previous calculation, which estimated federal workers made around 34 percent less, on average, than people in the private sector.

You might, like me, be scratching your head over this report since the conventional wisdom is that federal employees actually make quite a bit more than their private sector counterparts. The report gets to that:

Comparisons between federal and private sector compensation are fraught with controversy. Although Democrats and federal employee groups tend to cite FSC and BLS data, Republicans frequently point to calculations by the Congressional Budget Office, which uses a different methodology and found last year that feds made 17 percent more than those in the private sector from 2011 through 2015.

Alas, no explanation is given for the discrepancy. Digging into the reports, though, it’s clear that they are comparing in incredibly different ways. Here’s a summary from the latest CBO report (“Comparing the Compensation of Federal and Private-Sector Employees, 2011 to 2015“):

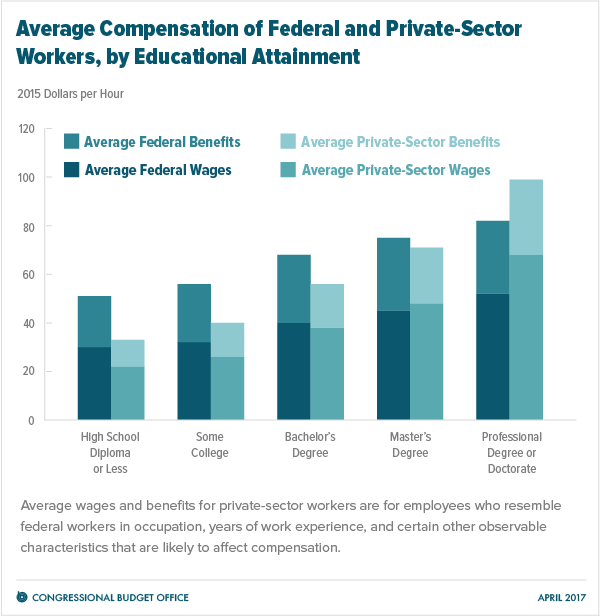

During the 2011-2015 period, the difference between the wages of federal civilian employees and those of similar private-sector employees varied widely depending on the employees’ educational attainment. The extent of that variation is evident in the differences in wages for workers with a bachelor’s degree (the most common level of education in the federal workforce), the least educated workers, and the most educated workers:

- Federal civilian workers whose highest level of education was a bachelor’s degree earned 5 percent more, on average, in the federal government than in the private sector (see figure below).

- Federal civilian workers with no more than a high school education earned 34 percent more, on average, than similar workers in the private sector.

- By contrast, federal workers with a professional degree or doctorate earned 24 percent less, on average, than their private-sector counterparts.

Overall, the federal government would have reduced its spending on wages by 3 percent if it had decreased the pay of its less educated employees and increased the pay of its more educated employees to match the wages of their private-sector counterparts.

Those estimates do not show precisely what federal workers would earn if they were employed in a comparable position in the private sector. The difference between what federal employees earn and what they would earn in the private sector could be larger or smaller depending on characteristics that were not included in this analysis (because such traits are not easy to measure). In addition, the estimated differences depend on how well the observable characteristics were measured in the samples of employees used by CBO and on other factors that are inherent in any statistical analysis. [emphasis mine]

That’s right: CBO isn’t comparing what people doing comparable jobs in the civil service and private sector. Because doing so isn’t easy. If only there were a government bureau that collected data on labor statistics, I’m sure there would be a more useful comparison.

Savvy readers might be thinking to themselves, “But what about the Bureau of Labor Statistics? Don’t they collect labor statistics?”

It turns out that, yes, they do.

Oddly enough, the Federal Salary Council uses those statistics, comparing apples to apples. Alas, they don’t seem to publish their report for the public to read; at least, I can’t find it anywhere. They don’t even seem to have their own website.

The National Treasury Employees Union, however, put out a press release at the time the above-cited CBO report was released:

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report today on federal pay and total compensation confirms the position long held by NTEU that the education levels and professional occupations of federal employees account for the differences noted time and time again in compensations surveys and studies attempting to compare federal and private-sector jobs.

Additionally, NTEU believes the jobs-to-jobs comparison by the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is the most appropriate method available of examining the differences between federal and private sector pay. BLS uses the more accurate comparison of actual job duties as opposed to employee characteristics, which CBO examined.

“While the CBO is an expert on budget scoring, the Bureau of Labor Statistics—which finds a consistent pay gap in comparable public and private sector jobs in favor of the private sector—is the expert in wage and compensation comparisons,” said Tony Reardon, National President of the National Treasury Employees Union (NTEU).

[…]

The federal workforce is the most highly-educated and highly-specialized workforce in the country, employing doctors, lawyers, economists, even rocket scientists, who could earn more in the private sector. In the private sector, workers without college degrees would include service industry jobs which do not exist in the federal sector.

“While news reports portray federal benefits as generous, federal employees do not receive paid dental or vision health insurance, nor do they get rich off their federal pensions or receive the kinds of monetary and non-monetary perks their counterparts in the private sector receive such as paid maternity leave, bonuses and stock options and incentive trips,” said Reardon. “Any statements describing federal jobs as having “greater security” is a joke given the kind of budgets and workforce reductions the Administration is focused on,” stated Reardon.

Reardon is a member of the Federal Salary Council. And, of course, the employees’ unions are going to be biased toward data that supports higher compensation. Still, BLS is simply in the business of collecting data.

A WaPo story (“Federal employees lag behind private sector workers in salaries by 32 percent on average, report says“) on the FSC report contains this:

Council members agreed to a review at the suggestion of the recently appointed chairman, Ronald Sanders, a longtime federal personnel official and consultant who is now a clinical professor of public administration at the University of South Florida. “If the goal [of the 1990 law] is to assure that the government can recruit and retain the best talent, what’s the best methodology to attain that goal?” he asked.

He said that should start with a better understanding of the current method, which uses several sets of Bureau of Labor Statistics data to compare nearly 100 occupations at various levels in 250 geographic areas.

“The math behind that is very, very complex,” Sanders said after the meeting, held at Office of Personnel Management headquarters. “While I’m sure it’s all consistent with data science principles, it’s hard to know what that number reveals and what it masks. … It’s not clear to me that it truly represents what the pay gap is.”

He noted testimony at the meeting from representatives of federal agencies in the Charleston, S.C., area who described serious difficulties in attracting and keeping employees despite paying various forms of incentives. However, according to the council’s own method, the area does not merit having separate, higher salary rates than are paid there now as part of the catchall locality.

Sanders is right that getting this right is complicated. Rather obviously, the CBO methodology, which controls only for education level, is absurd. The BLS is an honest broker working to provide useful data for comparison but jobs with similar titles vary considerably from industry to industry, within an industry, and in the public and private sectors.

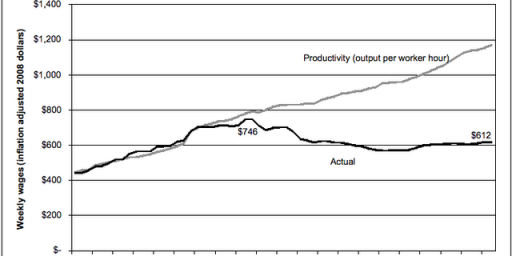

Further, salary alone is an imprecise comparison even if we could normalize it. We obviously need to measure total compensation–factoring in benefits, including retirement programs. Relatedly, it’s difficult to put a value on the relative employment stability federal workers have.

A recent CATO report (“Reforming Federal Worker Pay and Benefits“) begins with some charged rhetoric and rather slipshod analysis before getting at some useful information:

The [Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)] can be broken down by industry. Among 21 major sectors that span the U.S. economy, the federal government has the third highest paid workers after only utilities and management of companies.6 Federal compensation is higher, on average, than compensation in the information industry, finance and insurance, and professional and scientific industries.

[…]

Statistical studies by thinktanks have found a wage advantage for federal workers. A 2010 study by the Heritage Foundation found that federal pay was 22 percent higher, on average, than private-sector pay for comparable workers.12 A 2011 American Enterprise Institute (AEI) study found that federal pay was 14 percent higher, on average, than private-sector pay for comparable workers.13 As with the CBO study, these two studies found wage differences that varied by the level of the worker—less educated workers tend to do better in the federal government, while highly educated workers might do better in the private sector.

A 2010 USA Today analysis of more than 200 occupations found that federal workers typically have wages 20 percent higher than private sector workers.14 The analysis found that “federal employees earn higher average salaries than private sector workers in more than 8 out of 10 occupations.”15

The Bureau of Economic Analysis provides data on the average value of federal and private sector benefit packages.16 In 2016 federal workers enjoyed average annual benefits of $38,450, which compared to average benefits in the private sector of just $11,306. That large difference stems from more federal workers receiving certain types of benefits than private workers, and from particular federal benefits being more generous than those provided in the private sector.

Studies comparing federal and private benefits for similar workers have found a large federal advantage. The 2017 CBO study found that cost of employee benefits was 47 percent higher for federal civilian employees than for similar private-sector employees.17CBO found that “The most important factor contributing to differences between the two sectors in the costs of benefits is the defined benefit pension plan that is available to most federal employees.”18 The AEI and Heritage studies also found large federal advantages with respect to worker benefits.

Federal workers receive health insurance, retirement health benefits, a pension plan with inflation protection, and a retirement savings plan with a government match. They typically receive generous holiday and vacation schedules, flexible work hours, training options, incentive awards, and generous disability benefits.

Lily Garcia, a human resources specialist who contributes to the Washington Post, noted: “The primary advantages of working for the federal government are generous benefits, solid pay, and relative job security, a combination that is challenging to find in the private sector, even in the best of times.”19 Garcia summarized the federal benefits package:20

- “Health Care: The Federal Employee Health Benefits Program offers the widest selection of health care plans of any U.S. employer. Federal employees also have access to vision and dental plans, life insurance, flexible spending accounts, and long-term care plans.”

- “Paid Time Off: Federal employees enjoy liberal amounts of paid time off, including 13 days of sick leave per year, 10 paid federal holidays, and 13 to 26 days of paid vacation, depending on years of service.”

- “Retirement Benefits: Federal employees have access to retirement benefits through the Civil Service Retirement System or the Federal Employee Retirement System. Under both plans, retired employees receive an annuity, which is complemented by Social Security benefits and participation in the Thrift Savings Plan that offers 401(k)-type investment options.”

- “Family-Friendly Policies: Another notable benefit of federal employment is family-friendly policies, including flexible work schedules, telecommuting, part-time jobs, and job sharing. Not to mention the fact that federal employees enjoy first priority and subsidies at a number of top-notch day care facilities.”

There is another important benefit of federal employment: extremely high job security. Federal workers are supported by strong civil service protections, and about one-third of them are represented by unions.21 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data show that the rate of “layoffs and discharges” in the federal workforce is just one-quarter of the rate in the private sector.22

Federal workers are almost never fired. An investigation by Government Executive noted, “There is near-universal recognition that agencies have a problem getting rid of subpar employees.”23 Just 0.5 percent of federal civilian workers a year get fired for any reason, including poor performance and misconduct. That rate is just one-sixth of the private-sector firing rate.24 For the senior executive service in the government, the firing rate is just 0.1 percent.25 By contrast, about two percent of corporate CEOs are fired each year, which is a rate 20 times higher than in the senior executive service.26

All in all, the federal government is a very well-compensated place to work. A final piece of evidence can be found by looking at quit rates, or the rates that workers voluntarily leave their jobs. BLS data show that the quit rate in the federal government is just one-quarter the quit rate in the private sector.27 Federal workers know that they have a lucrative combination of compensation and job security, and so they stay much longer than in other industries.

CATO’s agenda is the opposite of that of the employees’ unions: they’re looking for reasons to cut the size and cost of the federal government. But the quoted pieces of the analysis above is fairminded enough, with two exceptions. First, while health insurance for federal workers is subsidized more heavily than in some sectors, it isn’t free. Relatedly, the vast array of plans available is actually a classic paradox of choice, as it’s virtually impossible for non-specialists to know which of the hundreds of options is the best value. Second, the “quit rate” seems an idiotic measure given the nature of the sectors. Whereas someone in industry unhappy with his boss generally has no alternative but find a job elsewhere, a similarly-situated federal worker can simply find a lateral position elsewhere in the federal government.

Regardless, this is a complex comparison. The CBO’s methodology is obviously hogwash. The FSC’s methodology is a much better baseline but certainly doesn’t tell the whole story.

Beyond the math, there’s philosophy. And I’m not sure CATO’s Chris Edwards is wrong here:

It is sometimes assumed that the federal government should employ the nation’s highest-skilled workers, and that it should pay top dollar to get them. But federal hiring of the very best workers imposes an “opportunity cost” on the economy by drawing talented people away from higher-valued activities in the private sector. Unlike, say, France, where the best university graduates historically have gone into government, the United States has historically prospered because the best and brightest have flocked to places such as Silicon Valley.

Federal pay should be reasonable, and we need competent people in federal jobs, assuming that the jobs are useful ones. But the government should not be one of the highest-paid industries in the nation. Indeed, an advantage of reducing federal pay would be to encourage greater turnover in the static federal workforce. That would help more young people enter government and bring in fresh ideas.

While I’m not in the civil service, I’m a federal employee and a reasonably well-compensated one. We ought pay enough to attract bright people into government service. But part of “service” is sacrifice to serve others. Soldiers, police officers, firefighters, and civil servants have never been among the best-paid occupations. The civic contract has always been that they work for the public good in return for decent pay, secure employment, and a decent pension. That seems a reasonable exchange.

During my time in public service, the thing I hated the most was the fact that nobody can get fired.

It meant that I had to work alongside people who knew they could just phone it in, and the rest of us did the real work.

The 2nd most hated part: Performance and Pay were entirely disconnected. Great performance meant getting new and interesting job duties. Simply hanging around got you more pay.

Perhaps such is the price of job stability.

One factor that all these analyses leave out is regional differences in pay.

I grew up in an aerospace town in Southern California, where a substantial number of people were doing very similar jobs, some for the federal government and others for private industries. There was no question that those in private industry made more, to the extent that any time a former federal employee switched to a private company everyone knew it was to make more money. The difference was primarily because the federal pay levels were set nationwide and while there was a mechanism for increasing pay based on local cost of living, it was not enough to make up the difference.

In an area with a lower cost of living, government jobs could pay more than their private counterparts, certainly.

Of course, this further complicates an already complex picture, but I wonder if those regional cost of living differences explain part of the disparity.

Very good write-up, James.

I do disagree with CATO’s Chris Edwards on this particular sentence, “Indeed, an advantage of reducing federal pay would be to encourage greater turnover in the static federal workforce.” While the evidence presented earlier suggested that bad government employees stick around too long, the solution is to target them rather than hope all your employees, good and bad, quit due to low pay. (In fact I would think it would be the good, motivated employees who are willing to put forth the effort of finding another job who would quit first.)

@Kari Q:

Since 1994 the GS pay scale has incorporated locality adjustments to account for cost of living differences. So a Federal employee who works in the San Jose metro area gets about a 38% increase above the “base” GS salary for their grade and step. A GS-10 step 5 would therefore earn about $76K in San Jose vs. the “base” GS-10 step 5 salary of about $55K.

@Franklin: This is typical when a company does downsizing, as well. Usually they offer “voluntary packages”, which means those who can see other opportunities elsewhere grab the money and run, leaving the deadwood behind. Which means the company now has even fewer people who might help in turning the place around, etc. etc.

It’s a common mistake.

There’s so much here to unpack, and all of it is so questionable.

Let’s start with “service” — are government employees called civil service because they have taken a vow of lower-wages and are donating their time to the government, or because their work is simply to benefit the civic as a whole? Do people who work in customer service take a similar vow of lower-wages to serve a company’s customers, or do they just have crappy jobs?

Police and firefighters are often very well paid. The low pay for soldiers is a national disgrace.

Is employment where you might be furloughed on a regular basis when congress fails to pass a budget or raise the debt limit and shuts down the government really secure?

And finally, pensions… the era of big public pensions is pretty much over. They are underfunded, and the Republicans have been trying to cut them on every level. State governments have reneged on their obligations, calling it reform. Pensions are no longer safe — if the employer cannot be trusted to pay deferred compensation, employees need to demand more immediate compensation.

As a former federal civil servant, I agree it is hard to calculate – especially the intangibles and also the opportunity costs. I think one also could do a comparison of total career pay and benefits – like a lot of public sector employees, federal workers can get a lot of back-loaded compensation in the form of a pension.

In my own profession – intelligence – the vast majority of private sector firms are government contractors doing government work, so it’s been pretty easy to compare. Pay is significantly higher in the private sector, but it comes at a cost. Here are some differences I’ve noticed:

– volatility: Contracts come and go, there is no job security and there will inevitably be periods where you are looking for work.

– Pension: There is none in the private sector, at best you’ll get 401k matching (which the feds also offer). And if you have other government service, like military service, that counts to your longevity.

– Taxes: Depending on the contract, you might be a 1099 employee and have to pay both sides of the social security tax – a 7% difference right off the top.

– Limited promotion opportunities: In the federal service, other than normal step increases due to longevity, there’s no way to get promoted without actually applying for a different job. There’s no way to increase your base compensation. And in a lot of locations and fields, you basically need to wait for someone to die or retire for a promotion opportunity. In the private sector, compensation is negotiable and can be more easily increased for good performance. There is also more churn which means more opportunities.

I had the same complaints as Tony W. Additionally, the stability was nice but also very frustrating. Getting hired into a civil service position can take a significant amount of time (as I’ve detailed before, it was a year from when I first applied to when I actually started working). The federal system is very slow to change – one reason why there are so many empty positions. Position paygrades are examined very infrequently – maybe once a decade – so base pay is slow to react to changes in a field.

Despite all this, I enjoyed my time in the civil service – for the most part. Not sure I would go back though.

@Kari Q: There’s a pretty substantial locality pay component. Indeed, part of the report that I didn’t cover in this post was a recommendation to add new ones, including one for Norfolk-Newport News. I don’t know how it factors into these comparisons, though.

@Franklin: I think he’s simply arguing that turnover is in and of itself a good thing, in that it brings in new ideas to counter “we’ve always done it that way.” He’s likely right but, as you say, the ideal would be to retain top employees and cycle out the worst. Alas, top employees often leave for more lucrative opportunities elsewhere.

@Gustopher:

Historically not so much but I’m sure it varies from locality to locality.

That hasn’t been true since the early 1980s. Pay and benefits are actually rather fantastic in the military and they’ve skyrocketed since 9/11. Meanwhile, the civil service sector has fallen way behind. A lieutenant colonel makes way, way more than a GS-13, even though they’re ostensibly at the same level.

With the exception of the sequestration furloughs in 2013, everyone always gets paid during government shutdowns.

Yes. But FERS is still head and shoulders above what most people in the private sector get.

@Andy: Yes, there is a lot of bureaucracy working for the bureaucracy. The hiring process is just atrocious and we’ve compounded it with a broken security clearance background check system.

@James Joyner:

No kidding. E-5s today are bringing in around $70K, half of which is non-taxable allowances. That’s more than double what I got as an E-5 in 1999, even including my jump pay and special duty pay. And the post-9/11 GI Bill is so much better than the Montgomery GI Bill I got that they’re barely even comparable.

@James Joyner:

Definitely true. If you look at technicians in the Reserve and Guard, the issue is pretty stark.

For those that don’t know, technicians are dual-hatted military/civil servants that keep Reserve and Guard units running day-to-day.

It’s comparing apples and oranges. Graduates of Top 20 law schools and graduates of other than Top 20 law schools belong to completely different categories from the standpoint of their career earnings expectations but they’re lumped together in the same category for purposes of the study. An orthopedist can expect to earn twice as much (at least) as a pediatrician but for the purposes of the study they’re in the same classification. And so on.

@Dave Schuler: Right. It’s really, really hard to make mass comparisons of millions of people.

I’ve been a GS-09 weather forecaster for about 4 1/2 years now, after I retired from active duty. Between the salary, military retirement pay and VA disability, I live fairly comfortably. But I definitely took a pay cut from what I was making as an active duty E-7. When I first started, my GS-09 pay plus my retirement check just about equaled my total military compensation … although now all of it was taxed. Without the retirement pay I’m not sure I could afford to live on just the civil service salary … which is why I get nervous when some of these think tanks talk about bringing back rules against “double dipping”.

I could quite likely make more money as a contractor … and I know enough people that I could probably get a contractor job. But as was mentioned above, I don’t think I would want to deal with the uncertainty. I like the fact that just like while I was on active duty, unless I do something to screw up pretty badly, I’m still going to have a job tomorrow, next week, and even next year.

@Todd:

You’re not joking–an E-7 at 20 years pulls down half again as much as a middle-step GS-9 in my locality.

While the details are indeed complicated, the broad outlines are not.

Low-skill workers make more money, get better benefits, and have more job security in federal government jobs than in private industry. By quite a bit.

In high-skill, high-education positions, federal workers make a small fraction of what the private sector pays, and considerably less than the non-profit sector.

[Edit — incorrect argument deleted. I was confusing fed/private with cleared/uncleared.]

I work for a nonprofit in a field where there are direct comps to my position in both government and private industry. The private industry guys make a bit more than I do; the feds make about 2/3 what I do, with worse benefits.

The point is that both sides can point at obvious abuses and stupidities. Federal secretaries and filing clerks are overcompensated and overly secure — partly as a side effect of attempting to create a workforce where racism and sexism aren’t sufficient grounds for firing. On the other hand, federal engineers and scientists and attorneys and economists are woefully underpaid, relative to the market. CATO loves that; they don’t want the government to be good at anything, because that makes it easier to claim that government can’t be good at anything. Apparently they think Wal-Mart put men on the moon…

@DrDaveT:

Yes. But we’ve increasingly turned these into contractor positions. And, as in the private and non-profit sectors, secretarial and clerical support has gone the way of the dinosaur, thus turning highly compensated professionals into part-time clerks.

It varies from industry to industry, even there. I’m making more than most social science associate professors, although those are mostly state rather than private sector jobs. I’m making quite a bit more than I would at George Mason and roughly what I would at Georgetown. Then again, I’m in a 12-month position, which scarcely exists elsewhere, making the comparison even more complicated.