Community Colleges Not Serving the Community

A key pathway to success for low-income citizens isn't working.

For a variety of reasons, most press coverage of higher education focuses on a handful of elite universities that serve the top 1 percent of students. Very little goes to regional teaching colleges that serve most students, while almost none goes to community colleges and technical schools that serve as the entryway for so many.

AP (“Community colleges are reeling. ‘The reckoning is here.’“):

When Santos Enrique Camara arrived at Shoreline Community College in Washington state to study audio engineering, he quickly felt lost.

“It’s like a weird maze,” remembered Camara, who was 19 at the time and had finished high school with a 4.0 grade-point average. “You need help with your classes and financial aid? Well, here, take a number and run from office to office and see if you can figure it out.”

Advocates for community colleges defend them as the underdogs of America’s higher education system, left to serve the students who need the most support but without the money to provide it. Critics contend this has become an excuse for poor success rates and for the kind of faceless bureaucracies that ultimately led Camara to drop out after two semesters.

With scant advising, many community college students spend time and money on courses that won’t transfer or that they don’t need. Though most intend to move on to get bachelor’s degrees, only a small fraction succeed; fewer than half earn any kind of credential. Even if they do, many employers don’t believe they’re ready for the workforce.

Now these failures are coming home to roost.

Community colleges are far cheaper than four-year schools. Published tuition and fees last year averaged $3,860, versus $39,400 at private and $10,940 at public four-year universities, with many states making community college free.

Yet consumers are abandoning them in droves. The number of students at community colleges has fallen 37% since 2010, or by nearly 2.6 million, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

“The reckoning is here,” said Davis Jenkins, senior research scholar at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. (The Hechinger Report, which produced this story, is an independent unit of Teachers College.)

Those numbers would be even more grim if they didn’t include high school students taking dual-enrollment courses, according to the Community College Research Center. High school students make up nearly a fifth of community college enrollment.

Yet even as these colleges serve fewer students, their already low success rates have by at least one measure gotten worse.

While four out of five students who begin at a community college say they plan to go on to get a bachelor’s degree, only about one in six of them actually manages to do it. That’s down by nearly 15% since 2020, according to the clearinghouse.

Two-year community colleges have the worst completion rates of any kind of university or college. Like Camara, nearly half of students drop out, within a year, of the community college where they started. Only slightly more than 40% finish within six years.

These frustrated wanderers include a disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic students. Half of all Hispanic and 40% of all Black students in higher education are enrolled at community colleges, the American Association of Community Colleges says.

While none of my degrees are from community colleges, I have some experience with that tier. My late father got his associate’s in police science at what we then called “junior college,” at Lee College in Baytown, Texas back in 1975. I taught at what was then Bainbridge College in Bainbridge, Georgia during the 1997-98 academic year. And my stepson has been attending Northern Virginia Community College (colloquially “NoVa”) the last three years.

I don’t have much recollection of my dad’s time at Lee College, as I was 8 and 9 years old when he attended, but he was an Army sergeant first class in his early 30s, so rather self-sufficient.

At least from the faculty perspective, Bainbridge was incredibly supportive, going out of our way to make classes available to students when and where they needed them. I personally taught classes in the daytime, evenings, on Saturdays, and at a high school 30 miles down the road. We were quite well-resourced, owing to the Georgia lottery funding, and had a pretty significant support staff.

Of course, those experiences are 48 and 25 years in the past, during an era when state support for higher education enjoyed strong, bipartisan support.

I have indeed noticed a different experience, albeit vicariously, at NoVa. While it’s generally regarded as quite excellent for its tier and seen as a low-cost pathway to the state’s elite public universities (the University of Virginia, William and Mary, and Virginia Tech), the level of institutional support has been shockingly poor. In order to schedule classes, my stepson has to drive to at least three different campuses that are 40 minutes or more away (there are six total, and I know he’s taken classes at Alexandria, Annandale, and Woodbridge). There is indeed a higher degree of “go and figure it out” than I’ve ever seen in a college setting.

The spurning of community colleges has implications for the national economy, which relies on their graduates to fill many of the jobs in which there are shortages. Those include positions as nurses, dental hygienists, emergency medical technicians, vehicle mechanics and electrical linemen, and in fields including information technology, construction, manufacturing, transportation and law enforcement.

Other factors are also contributing to the enrollment declines. Strong demand in the job market for people without college educations has made it more attractive for many to go to work. Thanks to so-called degree inflation, many jobs that require higher education call for bachelor’s degrees where associate degrees or certificates were once sufficient. And private, regional public and for-profit universities, facing enrollment crises of their own, are competing for the same students.

Many Americans increasingly are questioning the value of going to college at all.

But they are particularly rejecting community college. In Michigan, for instance, the proportion of high school graduates enrolling in community college fell more than three times faster from 2018 to 2021 than the proportion going to four-year universities, according to that state’s Center for Educational Performance and Information.

That’s truly a pity because community college is such a bargain, comparatively. Alas, there is something of a stigma associated with them, with most in academia not considering it “real college” or an associates a “real” degree. (Indeed, I’m somewhat bemused when I see an applicant for a faculty teaching job, which requires a Ph.D., listing an associate’s on their CV, as most consider it a mere waypoint to a bachelor’s.)

Those who do go complain of red tape and other frustrations.

Megan Parish, who at 26 has been in and out of community college in Arkansas since 2016, said she waits two or three days to get answers from advisers. “I’ve had to go out of my way to find people, and if they didn’t know the answer, they would send me to somebody else, usually by email.” Hearing back from the financial aid office, she said, can take a month.

Oryanan Lewis doesn’t have that kind of time. Lewis, 20, is in her second year at Chattahoochee Valley Community College in Phenix City, Alabama, where she is pursuing a degree in medical assisting. And she’s already behind.

Lewis has the autoimmune disease lupus and thought she’d get more personal attention at a smaller school than at a four-year university; Chattahoochee has about 1,600 students. But she said she didn’t receive the help she needed until her illness had almost derailed her degree.

She failed three classes and was put on academic probation. Only then did she hear from an intervention program.

“I feel like they should talk to their students more,” Lewis said. “Because a person can have a whole lot going on.”

While I’m always skeptical of the use of personal anecdote in news reporting, as there’s no way of assessing how typical the cases cited are—or even how fully the anecdote is fleshed out—they do comport with what I’ve seen at NoVa. Part of the problem is that so many of the faculty seem to be itinerant. Almost by definition, they have little stake in the school or incentive to engage in unpaid student advising. By contrast, permanent faculty at a teaching-oriented university not only naturally see that as part of their job but acquire enough familiarity with the larger institution to offer useful input.

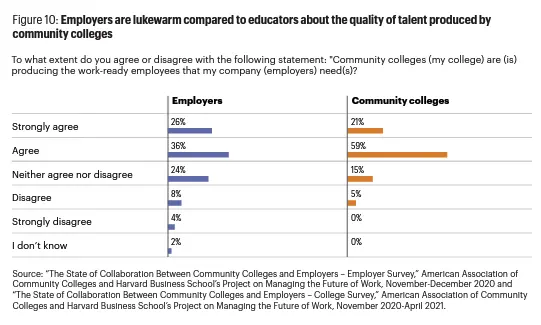

Employers, meanwhile, are unimpressed with the quality of community college students who manage to graduate. Only about a third agree that community colleges produce graduates who are ready to work, according to a survey released in December by researchers at the Harvard Business School.

I’m not sure what to make of that factoid.

The survey compares the responses of employers and community college educators. It would be far more useful to see how employers compared community college graduates to those with only a high school diploma and those with a four-year degree in the same field. For all I know, this is just a sign of grumpy employers.

Community colleges get less government money to spend, per student, than public four-year universities: $8,695, according to the Center for American Progress, compared with $17,540.

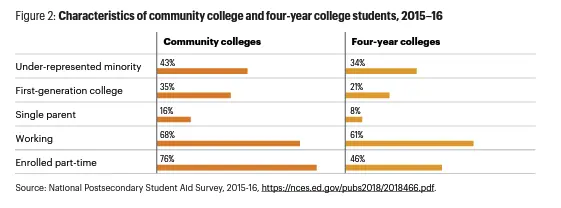

Yet community college students need more support than their counterparts at four-year universities. Twenty-nine percent are the first in their families to go to college, 15% are single parents and 68% work while in school. Twenty-nine percent say they’ve had trouble affording food and 14% affording housing, according to a survey by the Center for Community College Student Engagement.

Here, we get useful comparative information:

While the difference isn’t a stark as I would have guessed (but perhaps that’s a function of including dual-enrolled high school students, which would radically skew the data?) it’s still significant. Given the demographics, it seems obvious that resourcing support systems would be a high priority.

I went to CU Boulder, Colorado’s premier state university, in the late 1980’s. No one there did anything for me, “support” was nonexistent. No one cared whether I showed up for a class or failed classes until you hit academic probation and even then the university didn’t do much but provide access to a counselor. I saw so many people languish, fail, and drop out.

From what I heard, nothing much has changed (except the skyrocketing cost of tuition and housing).

So I’m of two minds regarding complaints that CC’s are not “supporting” students enough. Part of college is getting used to “adulting” where the college isn’t going to hold your hand and shouldn’t be expected to. But CC’s probably should be doing more of that compared to a competitive university.

How much and what kinds of support should they be giving students? The anecdotes don’t really tell us.

What help did she need that she didn’t get? What did she do to try to get that help? We don’t know. This is one reason why POV reporting like this is so annoying.

Finally, let’s also face the reality at CC’s are increasingly becoming extensions of High School. Many of the classes available to me in High School back in the 80’s are gone now and taught instead at the local CC. For example, my son is a HS senior and has been taking CC courses for the last two years to get some experience in machining and engineering, which the HS doesn’t offer – and this is a top-10 public HS in the state! But the HS does offer a yoga class!

We also need to face the fact that only about 50% of the population is going to succeed in college, unless we water down college considerably. Canada has the highest percentage of the population with “tertiary” education at about 55%. The hellhole known as Germany is at 27%. The US at 45%.

Anyway, I think part of the problem is that CC’s are being asked to do too many things at once:

– Offer classes for HS students that HS’s don’t teach anymore.

– Be a “gateway” to prepare students to transfer to a four-year university

– Provide technical certifications and training

– The various associate’s degrees

– Some also offer various types of adult education.

In Spanish No Va means won’t go, can’t go.

We have a pretty good community college here which specializes in police officer safety and training certification (POST), EMT training and restaurant management and cuisine and basic construction and metal fabrication. It also provides a ton of non-credit classes in everything from music, art, photography, bee keeping gardening, etc. for the community. It doesn’t claim to prep students to go on to a BA.

@Andy: makes some good points. I’d agree that colleges provided limited support when I was enrolled, but a significant difference in my HS experience and I suspect Andy’s, is that our HS’s did a far better job in preparing us for adulthood than many HS’s do today.

As far as business having a low view of CC’s, I’ll respond that they are expecting something that the schools can’t deliver. They are simply too cheap invest in training their employees, because they are fearful that the employee will take that training and go to a higher paying employer.

That CC’s get less state support than 4 year schools, which are already under supported is close to the root of the problem.

@Sleeping Dog: We used to have a “vocational school” where people who weren’t doing well in grades 9-12 got shunted to–IIRC it was mainly auto repair and learning how to type for the secretarial pool bound females. Which I find ironic because now with the amount of computer chips etc. in vehicles you now need an engineering degree to even start deciphering what’s wrong with a modern vehicle, plus now everyone learns to type….

@Andy:

Back in the dark ages while you were at CU, I was in grad school and substitute teaching while working on the MA that I would need to enter/stay in the teaching profession.* At one of the districts I worked at, the school was considering starting an auto shop program that would be able to make students “job ready”–as in prepared to work as someone other than the kid who drives the service department shuttle and hoses down the lot. They found they were going to have to abort the plan when they discovered that the workstation that would allow the students do work beyond changing oil and spark plugs was going to be about a million and a half and would accommodate one student at a time. And this was before dongles and extensive computer interfaces. Just last week though, I was at my local high school with the kids taking auto shop. They don’t actually learn any auto repair, but they do come out of the program with the necessary safety training and some familiarity with basic auto maintenance. And they do cool stuff like take the plastic bumpers of their cars (my understanding is that they mostly have “volunteer” cars in the shop that people don’t need back right away). We also have some CAD/CAM programs that replicate machining using a 3D printer. These programs were part of a $46 million bond issue that the district passed third time out. But yeah. Career and Techinical education is pretty basic at high school level. Always has been from what I’ve seen and remember from growing up in Seattle. Culinary education at our high school is better though. We found a retired chef who wanted to teach, and his program comes closer to being genuine vocational education with students planning menus, writing their own recipes and budgeting for making the same, and occasionally doing some contract catering work. All for an industry that leads in failure rate for business startups. (Hmmm…)

But don’t knock yoga unless you can do it. We also have yoga classes, and in addition to attracting a significant following among students, they assist the school in increasing the overall participation in PE for among students who aren’t the jocks and usually spent their time in gym class sitting on a bleacher waiting for class to be over.

@Sleeping Dog:

Yep, High Schools offered (and some were mandatory) classes in various life and soft skills. I learned basic budgeting, typing, and mechanical skills, and the school even had a driving program where they brought in simulators (crude in those days). There were options to get basic skills to enter the workforce immediately after HS. Lots of stuff was “hands-on.” That is all gone now, as schools primarily focus on college prep.

When I was teaching at Clark College in Vancouver, we had ~60 full-time faculty and ~250 adjuncts (excluding full-time faculty who took extra adjunct work). Adjuncts are the part of the system that allow schools to enroll so many students by providing the shadow workforce that works for as little as 10% of the cost of faculty.

I suspect that it is less about incentive to advise than it is about lack of information about programs at schools where a typical adjunct spends less than 15 hours a week and participates in few program-related activities beyond lecturing. Bur your follow-up comment noted that point also.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

Thanks for sharing that. Seeing some exceptions is nice, but I don’t think that’s the norm.

To be more clear about my main complaint, it’s that many kids aren’t even being exposed to similar “hands on” activities in schools. These kids don’t know these options exist because most schools don’t offer them except as a listing in the course catalog for a class actually taught by the CC. HS doesn’t need to offer full car repair or teach on expensive diagnostic equipment – instead, it should focus on fundamentals and concepts designed to expose kids to it.

For example, the entry-level shop class in my HS had the class disassemble and reassemble a lawn mower engine, show how it works, show what each part did along the way etc. It didn’t remotely qualify me to rebuild any engine, but learning how they work in a practical way was really valuable. You could do the same thing today with an electrical engine, or compare the two, since gas engines are still around.

The GOP’s war on education is bearing fruit.

Well, yes and no. What is taught in an engineering degree is not likely to help you diagnose a vehicle. But this has been true from the start. Now someone who pursued an engineering degree is more likely to be someone with the mechanical and now electrical interest.

Look at some of the auto diag youtube channels, those guys didn’t learn from a school. It is following the same path as the industrial revolution, the innovation and advancement is coming from the workshops not the universities/colleges.

@Andy:

A half-sized buggy whip and you had to trade off playing the horse?

A friend of mine’s kids were secular home-schooled. Both took high school classes and did some community college work concurrently, earning college credits. They each started college with enough credits that they were basically midway through their sophomore year. It saved the family a bunch of money. I’ve wondered why more people don’t do this.

My experience in Midwestern high school was different. Education in living skills consisted of home ec for girls and we had a year of shop class, 1/2 wood and 1/2 metal. No budgeting, typing etc. Typing was a class for girls on the secretary-“business” track. Far as i can remember there wasn’t much help for kinds in high school or undergrad if you did poorly. There was a lot of help if you needed it in med school.

“I’ve wondered why more people don’t do this.”

Credits often dont transfer. Even if they do the courses may only count as general ed courses and not towards your major. Hard to find out ahead of time what will transfer and what wont. If the course you took at the CC was a foundational course and you are going to rely upon what you learned and maybe apply it at 2nd level courses you may have some difficulties as the CC courses may have been surgery level courses not aimed at people majoring in that area. ( I did two years at a state extension school then transferred to another school. Was facing some of these issues but the admin person at new school was a veteran and so was I so he made sure all my credits were accepted.)

Steve

@OzarkHillbilly:

I don’t think that’s the answer here, easy though it may be. This phenomenon seems to be common to red and blue states. We’re paying more to take care of the old and more for K-12 and more for prisons. Higher ed has been getting squeezed for at least 30 years now.

I’m struggling to think of anything useful I learned in school. I could already read, and that’s the key bit of learning. I would say I learned to be a smooth and credible liar. I learned indifference is a superpower. Learned some arrogance, some contempt, figured out early on that I had no use at all for my fellow boys, while I nursed vague hopes as to girls. Learned to hate athletics and math. A general aversion to authority and institutions. But positive take-aways? Even now, looking back over a long life, I think, thank God I got the fuck out..

@OzarkHillbilly:

If there ever was a GoP war on education, it failed. Liberals dominate education, and spending has consistently grown, etc. I think the problems are systemic and not partisan.

@steve:

This one is the big point. You have to be wanting to transfer to a school that has a coordination agreement with the 2-year from which you are transferring the credits. Normally, that means a state school or a regional in an adjacent state. The fact that they only count toward general ed courses has to do with agreements between CCs and the flagships and regionals in their states not to encroach on the next schools’ territories. Even so, taking out most of year one is considered a significant advantage given that year one is where the courses the schools use to try to “cull the herd”* are.

Your other comment about your advisor is also important to help us all remember that transferring credits is a game and the school can use whatever rules that it wants to. When I was taking my teaching certificate work, the school I transferred to determined that I was difficient on music ensemble credits–not because I hadn’t played in enough ensembles, but because ensembles at their school counted for 2 credits, so my one-credit ensembles from the first school were inferior.

*By “cull the herd,” I’m thinking about a story from one of my ed professors who noted that while she’d been a teaching assistant in grad school, her university had a policy that 50% of students who took English 101 and Math 101 were to receive failing grades regardless of their success in the courses. I ran into a similar policy teaching at Woosong U in Daejeon where we weighted the grades so that only 15% of the students could be awarded grades of either A or B. But we didn’t have mandatory failure rates, too, fortunately.

Disappointed to see Shoreline CC mentioned at the top as I was a student there back in 93-95. Got my AA degree there then qualified for a transfer to UW.

To be fair to community colleges though success is a lot harder to quantify as students are much more likely to have non-traditional educational goals.

@Jen: That’s what my oldest daughter is doing. These last two semesters have all been college-credit classes, with the exception of Economics.

Good lord. The point of a Community College is to allow young people to make mistakes with the lowest possible consequences. Do you think you might make it in college? Give it a try. Did you screw up once, or twice? Try again.

There are lots of 19 year olds whose lives aren’t on rails. They may have no idea about what to do with themselves. They might try a trade school, but those are expensive, and probably won’t let you try again if you fail.

My entire lifetime we have been less and less willing to spend money to cultivate talent. And if even one person fails out and becomes a roofer, that’s evidence that “the system isn’t working”. No, the system is working. That’s exactly what the system looks like when its working.

My sister went back to CC when she was over 30 and her kid was old enough to be in school. THEN, she got into a 4 year, got a degree, and a Masters and then became a social worker. A good one, a valued one. She could never have done any of that at age 18.

The thesis is garbage. The argument is that “students aren’t making it” therefore the system is worthless. That’s the wrong metric.

I went to night school at San Antonio Junior College as a young G.I. While several courses were on par with my high school levels, others had fantastic teachers. Several were military officers moonlighting. I studied under three Ph.D.’s that were full-time military staff. Inasmuch as night school was for those of us who were serious about our education while on active duty, I fondly remember moving on and ultimately got a B.S. in Biology. I never would have made it without the Junior College night school opportunity. P.S. The G.I Bill certainly helped also!!!!