Desert Storm Syndrome

Technology has saved the lives of countless American soldiers. But it's made going to war easier.

Cheryl Rofer uses my Atlantic article on Perpetual Wars as a jumping off point:

I’d like to add a couple of things on the practical side. Americans love technology. So it’s easy, too easy, to believe that we’ll put our high-tech begoggled and battery-using military on the ground, and they’ll fix it all. After all, they’re our kids, nice guys who will be happy to have a cup of tea with the tribal leaders. And if that doesn’t work, we’ll send in those carefully targeted missiles. No sweat.

[…]

The American public loves a quick fix, and if it’s by technology, it’s a sure sell.

The military, of course, embodies that quick technological fix, and the federal budgets have aided and abetted the image and the reality. Even Robert Gates, the Secretary of Defense, has suggested that some of his Department of Defense budget might be diverted to the State Department. But Congress loves those gizmos, too, especially when they’re manufactured in their districts. And State manufactures many fewer gizmos.

While he’s often the butt of jokes in military circles (or, perhaps, retired military circles by now) Jimmy Carter and the Offset Strategy of his Secretary of Defense, Harold Brown, was a line of demarcation in U.S. defense policy. He made a conscious decision to trade gold for blood, spending large sums on high tech gizmos that worked in concert with one another to minimize American military casualties to the maximum extent possible. Ronald Reagan gets most of the credit because he doubled down on this policy and wrecked the budget pursuing it. Since then, it has been bipartisan wisdom that we must spend more on defense than all our adversaries and allies combined.

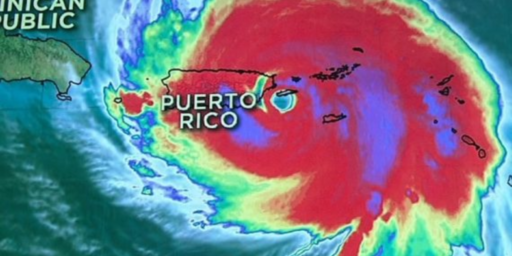

We saw flashes of this is Libya in 1986 but Operation Desert Storm was the coming out party. U.S. troopers imposed their will on the fifth largest army in the world in 100 hours (if we don’t count weeks of preparatory bombing for no apparent reason). While those of us on the ground didn’t know it at the time, our comrades walking around in flip-flops in the rear area were in roughly as much danger as we were. We suffered 148 battle deaths and 145 nonbattle deaths–but the battle deaths include 35 from friendly fire and 28 from a SCUD attack on Dhahran, Saudi Arabia–about as fear in the rear as it got.

Not only did this go a long way to erasing the dreaded Vietnam Syndrome, it created one of its own: Desert Storm Syndrome*–the notion that wars will be quick, painless, and entertaining.

When, two and a half years later, 18 Rangers were killed at the Battle of Mogadishu, it was positively horrifying. That they’d taken something like a thousand bad guys with them was of small comfort: War was supposed to be a video game. So, for the rest of the 1990s, we did all our fighting from several thousand feet. In Kosovo, this drastically compromised the mission; but it kept American casualties to a minimum. We lost two in an Apache helicopter crash–during a training exercise. Which, naturally, prompted questions about why we would use aircraft flying low and slow. (Not so much, oddly, about what the hell we were doing in Kosovo.)

Thus far, we’re taking the same approach to Libya: Steadfastly refusing to use ground troops despite a political objective (regime change) that would be much easier to achieve with their use.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, the initial operations were Desert Storm on steroids. In both cases, American forces took their objectives with amazing speed and precision, suffering a relative handful of casualties. But the longer term missions required sustained deployment of ground troops for counterinsurgency, stabilization, development, and other non-kinetic or only occasionally kinetic activities. Here, technology is much less decisive.

One would think that Iraq, in particular, would have done for Desert Storm Syndrome what Desert Storm did for Vietnam Syndrome. But it doesn’t seem so. Unless the lesson is simply to go back to fighting from long range and hoping for the best.

___________

*While the idea is not original with me, the coinage may be. It should not be confused with”Gulf War Syndrome,” which is something else entirely.

Part of it, no doubt.

To me … Iraq and Afghanistan symbolize glaring failure of a very simple concept I learned when I first became an NCO long years ago: Proper Prior Planning Prevents Piss Poor Performance.

Nothing in war is easy unless you are a REMF or an armchair quarterback.

Rock, weren’t both of those wars militarily successful?

The conquests were swift, at which point the early (f’d up) neocon nation-builders came in, with literally plane loads of cash, and a completely unrealistic expectation of how the world (and especially that part of the world) worked.

After which, the military was asked to police a train wreck.

What you say is true, John. The train wreck occurred and the solution was to throw cash at the result. That’s a favorite solution for all politicians. You know, if it’s broke throw money at it. If it ain’t broke throw more money at it. That’s why we are still in both countries. And eventually when we finally do leave the train wrecks will still be there. It’s like taking a crap – the job ain’t finished until the paperwork is done and we are using paper you can poke a finger through – cash. But down on the ground at the point of the spear, nothing is easy despite our superior technology.

I think you’ve got to distinguish between tactical objectives and strategic objectives. The tactical objectives were achieved both in Iraq and Afghanistan. I think it’s arguable that there were no achievable strategic objectives in either instance. For me the moral of the story is that you don’t go to war without achievable strategic objectives.

Note: an objective that’s achievable by doing X when you’re not willing or able to do X is not achievable.

James,

I’m not sure you or Cheryl are getting the big picture here, which is the proper use of military force. The US military has become the go-to foreign policy “problem” solver of choice and is simply being misused.

Further, you both miss the point on technology. Those “gizmos” are critical for fighting and winning conventional engagements and that is what they were designed to do. That they fail to help win the “armed nation-building” and air-power-only conflicts our politicians put us in is both unsurprising and irrelevant to the utility of the “gizmos.”

Ultimately, the problem is that we, as a nation, don’t have any kind of grand strategy to inform America’s role in the world. We are simply exploiting our hegemony in pursuit of perceived interests, but that is an unsustainable path.

As you and others have alluded to in other pieces, it seems to me that the real Desert Storm Syndrome isn’t gizmos but the volunteer force.

Gizmos dramatically reduce the casualty rate, but it is the absence of draft that makes war an abstraction for the vast majority of the public, which in turn removes any real pressure on elected officials to end military involvements.

Any war we are not willing to lose lives to fight is a war not worth fighting.

@Andy: We largely agree here. I have argued going back to the early 1990s that we over-use military force as a tool. My quibble with you is that, given that our political leaders have directed that force be used in the way that it has, the fact that we’re not training and equipping our armed forces accordingly is problematic.

@Ken: Again, I largely agree. But it’s not inconceivable that the president could identify a legitimate interest at stake achievable by the deployment of military force and deem it only worth very small risk to American life. To take a recent example: Getting Osama bin Laden is a just use of force and worth risking the lives of a SEAL team. But it’s not worth thousands dead.

And, in fairness, while an all-volunteer force has changed the political calculus of going to and sustaining wars considerably, I’d argue that we’re actually more casualty-averse than ever. Perhaps that’s because those doing the ordering come almost exclusively from the class that never went into harm’s way, whereas in the old days almost all presidents and congressmen had served.