Deutschland Unter Alles

Germany's economy is among the worst in the OECD.

AP economics reporter David McHugh: “Germany went from envy of the world to the worst-performing major developed economy. What happened?“

For most of this century, Germany racked up one economic success after another, dominating global markets for high-end products like luxury cars and industrial machinery, selling so much to the rest of the world that half the economy ran on exports.

Jobs were plentiful, the government’s financial coffers grew as other European countries drowned in debt, and books were written about what other countries could learn from Germany.

No longer. Now, Germany is the world’s worst-performing major developed economy, with both the International Monetary Fund and European Union expecting it to shrink this year.

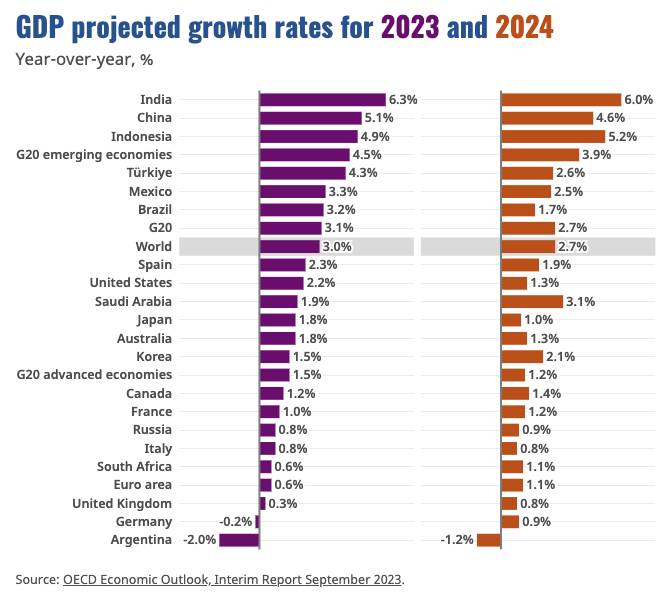

The link, alas, is to a July report, also by McHugh, noting that “the International Monetary Fund forecast this week that Germany would be the globe’s only major economy to shrink this year, even with weak economic growth around the world amid rising interest rates and the threat of growing inflation.” This chart, on the front page of the OECD website, provides the context I was looking for:

Germany has been outperformed by every major country save Argentina this year and is projected to be near the very bottom again next year. Quite the turn of events, indeed.

It follows Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the loss of Moscow’s cheap natural gas — an unprecedented shock to Germany’s energy-intensive industries, long the manufacturing powerhouse of Europe.

Germany decided to abandon its decades-long nuclear energy program in the wake of the Fukushima disaster in 2011, with the last of the plants shuttered earlier this year. This left them reliant on Russian gas and, ironically, their own coal—which they’ve naturally also been trying to wean themselves from to combat climate change.

The sudden underperformance by Europe’s largest economy has set off a wave of criticism, handwringing and debate about the way forward.

Germany risks “deindustrialization” as high energy costs and government inaction on other chronic problems threaten to send new factories and high-paying jobs elsewhere, said Christian Kullmann, CEO of major German chemical company Evonik Industries AG.

From his 21st-floor office in the west German town of Essen, Kullmann points out the symbols of earlier success across the historic Ruhr Valley industrial region: smokestacks from metal plants, giant heaps of waste from now-shuttered coal mines, a massive BP oil refinery and Evonik’s sprawling chemical production facility.

These days, the former mining region, where coal dust once blackened hanging laundry, is a symbol of the energy transition, dotted with wind turbines and green space.

The loss of cheap Russian natural gas needed to power factories “painfully damaged the business model of the German economy,” Kullmann told The Associated Press. “We’re in a situation where we’re being strongly affected — damaged — by external factors.”

After Russia cut off most of its gas to the European Union, spurring an energy crisis in the 27-nation bloc that had sourced 40% of the fuel from Moscow, the German government asked Evonik to keep its 1960s coal-fired power plant running a few months longer.

The company is shifting away from the plant — whose 40-story smokestack fuels production of plastics and other goods — to two gas-fired generators that can later run on hydrogen amid plans to become carbon neutral by 2030.

One hotly debated solution: a government-funded cap on industrial electricity prices to get the economy through the renewable energy transition.

The proposal from Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck of the Greens Party has faced resistance from Chancellor Olaf Scholz, a Social Democrat, and pro-business coalition partner the Free Democrats. Environmentalists say it would only prolong reliance on fossil fuels.

Kullmann is for it: “It was mistaken political decisions that primarily developed and influenced these high energy costs. And it can’t now be that German industry, German workers should be stuck with the bill.”

Unlike the United States, with only two political parties (one of which has little interest in governing) the Germans have a form of proportional representation and tend to have coalition government. They also have a long history of government, business, and labor working together to balance their competing interests. Still, this is a wicked problem and one largely of their own making.

The price of gas is roughly double what it was in 2021, hurting companies that need it to keep glass or metal red-hot and molten 24 hours a day to make glass, paper and metal coatings used in buildings and cars.

A second blow came as key trade partner China experiences a slowdown after several decades of strong economic growth.

These outside shocks have exposed cracks in Germany’s foundation that were ignored during years of success, including lagging use of digital technology in government and business and a lengthy process to get badly needed renewable energy projects approved.

Other dawning realizations: The money that the government readily had on hand came in part because of delays in investing in roads, the rail network and high-speed internet in rural areas. A 2011 decision to shut down Germany’s remaining nuclear power plants has been questioned amid worries about electricity prices and shortages. Companies face a severe shortage of skilled labor, with job openings hitting a record of just under 2 million.

And relying on Russia to reliably supply gas through the Nord Stream pipelines under the Baltic Sea — built under former Chancellor Angela Merkel and since shut off and damaged amid the war — was belatedly conceded by the government to have been a mistake.

Now, clean energy projects are slowed by extensive bureaucracy and not-in-my-backyard resistance. Spacing limits from homes keep annual construction of wind turbines in single digits in the southern Bavarian region.

A 10 billion-euro ($10.68 billion) electrical line bringing wind power from the breezier north to industry in the south has faced costly delays from political resistance to unsightly above-ground towers. Burying the line means completion in 2028 instead of 2022.

That’s a hell of a delay, but an understandable one. Modern societies concern themselves with aesthetics.

Massive clean energy subsidies that the Biden administration is offering to companies investing in the U.S. have evoked envy and alarm that Germany is being left behind.

“We’re seeing a worldwide competition by national governments for the most attractive future technologies — attractive meaning the most profitable, the ones that strengthen growth,” Kullmann said.

He cited Evonik’s decision to build a $220 million production facility for lipids — key ingredients in COVID-19 vaccines — in Lafayette, Indiana. Rapid approvals and up to $150 million in U.S. subsidies made a difference after German officials evinced little interest, he said.

“I’d like to see a little more of that pragmatism … in Brussels and Berlin,” Kullmann said.

This is a strange reversal. The United States has long been adverse to industrial policy while most OECD countries have not.

Scholz has called for the energy transition to take on the “Germany tempo,” the same urgency used to set up four floating natural gas terminals in months to replace lost Russian gas. The liquefied natural gas that comes to the terminals by ship from the U.S., Qatar and elsewhere is much more expensive than Russian pipeline supplies, but the effort showed what Germany can do when it has to.

However, squabbling among the coalition government over the energy price cap and a law barring new gas furnaces has exasperated business leaders.

Evonik’s Kullmann dismissed a recent package of government proposals, including tax breaks for investment and a law aimed at reducing bureaucracy, as “a Band-Aid.”

Germany grew complacent during a “golden decade” of economic growth in 2010-2020 based on reforms under Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder in 2003-2005 that lowered labor costs and increased competitiveness, says Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg bank.

“The perception of Germany’s underlying strength may also have contributed to the misguided decisions to exit nuclear energy, ban fracking for natural gas and bet on ample natural gas supplies from Russia,” he said. “Germany is paying the price for its energy policies.”

The closure of the nuclear plants was a massive own-goal. Presumably, though, it was a politically popular one. Whether there’s an appetite to rethink the policy—and whether it’s even reversible in the near term—I haven’t the foggiest.

Schmieding, who once dubbed Germany “the sick man of Europe” in an influential 1998 analysis, thinks that label would be overdone today, considering its low unemployment and strong government finances. That gives Germany room to act — but also lowers the pressure to make changes.

The most important immediate step, Schmieding said, would be to end uncertainty over energy prices, through a price cap to help not just large companies, but smaller ones as well.

Whatever policies are chosen, “it would already be a great help if the government could agree on them fast so that companies know what they are up to and can plan accordingly instead of delaying investment decisions,” he said.

These are big, fraught decisions. Fast likely isn’t in the cards.

Given Germany’s economic conservatism, especially when it comes to inflation, I wondered if part of this under performance might be due to an anemic COVID stimulus. But no, Germany’s packages totaled roughly the same as ours on a per capita basis. And their current inflation rate is about twice ours.

This is all just terrible framing.

Germany suffers from two simultaneous problems, neither of which is of their own making.

1) The German economy relies to a significant degree on energy-intensive manufacturing.

2) Germany is a big exporter of advanced equipment and machine tools to China.

Now, energy got a lot more expensive because the Russians ridiculously overestimated their own military power relative to Ukraine’s and China is slowing down, partly due to Chinese mismanagement of their own economy.

So yeah, that hurts.

In hindsight, the Germans could certainly have made other decisions (but even with all their nuclear power plants up and running, they still used a LOT of Russian oil and gas), but it is hard to plan for other people’s miscalculations. We tend to assume that the other guys are rational, too. Unfortunately, that’s not always the case.

In short, this says nothing about Germany, except for the fact that it is hard to grow your economy when confronted with two crises (not of your own making) simultaneously.

But that should hardly be a surprise.

@drj:

Except those problems were of their own making, for reasons that looked good at the time, but have long been seen to have serious flaws.

There were a lot of people in Europe (the government of France in particular) who had been, for years, tapping Germany on the shoulder and saying “over reliance on cheap Russian gas and shuttering the nukes is not a very good idea.”

Nor, for that matter, is effectively suppressing domestic consumption in favour of capital goods exports to China, because it ticks the boxes of Teutonic “virtue”.

Nobody can be quite as annoyingly smug as a German politician when “alles ist gut”.

It was an economic model that worked, at the time that it worked, but spotting its flaws and potential failure modes did not take Nostradmus.

It was forseeable and forseen.

Actually, it’s even funnier when you look at the 2024 projections (not that I necessarily believe these, but – hey – it’s all we have).

“Germany is suffering a major crisis! They closed down their nuclear power plants and their bureaucracy slows everything down!”

Projected growth for 2024:

Germany: +0.9% (up from -0.2%)

G20 advanced: +1.2% (down from +1.5%)

US: +1.3% (down from +2.2%)

And all that with Russia still out as energy supplier and China’s growth slowing down even further.

Looks pretty resilient to me!

@JohnSF:

I’m not trying to give the Germans perfect marks, but it is ridiculous to pretend that they ended up in some existential crisis due to severe and structural economic mismanagement.

It’s clickbait.

@drj:

The crisis is not existential, true enough. They are just at the low end (with the UK) of the G20, and not by an enormous amount.

And for consequences of serious mismanagement, see Argentina!

OTOH, actual shrinkage is always more painful than just stagnation.

The real G20 exception is the US (and Spain, for some idiosyncratic reasons), thanks to some relatively sensible economic policy decisions; the Trump administration was not great, but also not appalling in this area. President Biden’s administration has been very effective. And the 2020-22 Congress for that matter.

So, its not to be exaggerated. But it is not going to be easy for Germany to transition away from the cheap gas/capital-goods exports model. Though in fact, this may be beneficial for Europe as a whole.

It provides greater political space for the arguments from France, Italy, and Scandinavia that de-carbonisation and related challenges is going to require a co-ordinated continental approach (an EU equivalent of the IR Act) rather then the German preference for just “rely on the free market and business level collaboration”.

@drj:

I see what you did there…..

Like Brexit, the advocates of shutting down the nukes, focused on the public’s fears and chose to discount the risks. Another example of roosting chickens.

Looking at the graphs that accompany this post, I am glad to live in the US where we have a steady, calm hand on the tiller.

Every economy has ups and downs; no nation’s growth is a straight line. Let’s not crow too much during up periods, and let’s not despair during the downs. Germany will have upcycles soon enough. They have a industrial base that goes back centuries. The swords and armor I saw at a museum of medieval weapons in Edinburgh were made in Germany. They are resilient. After the massive destruction of WW II, Mercedes won at LeMans in 1952.

@drj: Agreed, Germany may be underperforming economically for the reasons stated and probably other reasons but not by much.

@JohnSF:

There were also people saying that by integrating Russia’s economy and interests with Europe that it would reduce the chances of any kind of major war. Economic mutually assured destruction.

Didn’t work out that way, but it was a reasonable argument. It wasn’t a universally condemned idea.

I read this post this morning and went to do stuff. I came back here and was about to check out the forum and saw the post again and thought to myself, “why do I care what the Germans are doing, they’re irrelevant.” I was kinda stunned with that thought and after a bit I realized while I think the Germans (qua Germans) are irrelevant, Europeans (or Germans/French/Spanish/Blahblahblah as Europeans) are not.

Like, we don’t consider Texas relevant on the world stage, It’s the Americans part that matters. I think the self-immolation of the UK adds to this for me. Like, these pieces only matter because they are parts of a much greater whole.

@Gustopher:

Wandel durch Handel

(But the vandals stole the handle’s)

Those people largely being in Germany; and post-2014, almost only in Germany (well, and Hungary) It wasn’t universally condemned out loud, but a lot of people after 2014 began telling Berlin they were being over-sanguine about that project.

@JohnSF:

Can you explain that one?

@MarkedMan: Bob Dylan reference?

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=MGxjIBEZvx0

@Scott O: Wow. Deep cut.

@MarkedMan: I’m old. That song is also the inspiration for the name of the Weather Underground.

“ The group took its name from Bob Dylan’s lyric “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows”, from the song “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (1965)”

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weather_Underground

@MarkedMan:

@Scott O:

LOL Apologies for the oblique Dylan quip, but I can seldom resist that one when Handel durch Wandel comes up.

Well spotted, Scott O!