Elie Wiesel, Holocaust Survivor, Author, And Human Rights Advocate, Dies At 87

A man who survived great horrors to become a tireless witness for truth and advocate for human rights has passed away.

Elie Weisel, who as a child was sent with his family to a concentration camp and managed to survive to become one of the great witnesses to the ultimate act of man’s inhumanity to man, has died at the age of 87:

Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, the memory keeper for victims of Nazi persecution, and a Nobel laureate who used his moral authority to force attention on atrocities around the world, died July 2. He was 87.

His death was confirmed in a statement from Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Other details were not immediately available.

By the time of Mr. Wiesel’s death, millions had read “Night,” his account of the concentration camps where he watched his father die and where his mother and younger sister were gassed. Presidents summoned him to the White House to discuss human rights abuses in Bosnia, Iraq and elsewhere, and the chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee called him a “messenger to mankind.”

But when he emerged, gaunt and near death, from Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945, there was little indication that he — or any survivor — would have such a presence in the world. Few survivors spoke openly about the war. Those who did often felt ignored. Decades before a Holocaust museum stood in downtown Washington and moviegoers watched Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List,” Mr. Wiesel helped force the public to confront the Holocaust.

“The voice of the person who can speak in the first-person singular — ‘This is my story; I was there’ — it will be gone when the last survivor dies,” Holocaust scholar Deborah Lipstadt said in an interview with The Washington Post. “But in Elie Wiesel, we had that voice with a megaphone that wasn’t matched by anyone else.”

Mr. Wiesel was in his 20s when he wrote the first draft of “Night” after 10 years of silence about the war. Today, perhaps the only volume in Holocaust literature that eclipses the book in its popular reach is Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl.”

Mr. Wiesel was less than nine months older than the aspiring writer who chronicled her existence in an Amsterdam hideaway, but “Night” is rarely characterized as the narrative of a young boy. While the diary ends days before Nazis arrest Anne and her family, “Night” puts readers in Auschwitz within the first 30 pages.

Short enough to be read in a single sitting, the volume captures all of the most salient images of the Holocaust: the teeming ghettos where many struggled to believe that the worst was yet to come, the cattle cars, the barracks, the smokestacks. The book also contains one of the most famous images in the vast theological debates surrounding the slaughter: the vision of God with a noose around his neck.

” ‘For God’s sake, where is God?’ ” Mr. Wiesel hears a man ask as they watch a boy hanged at Auschwitz.

“And from within me, I heard a voice answer,” he writes. ” ‘This is where — hanging here from this gallows.’ ”

At the encouragement of the French writer François Mauriac, whom he interviewed as a journalist in the 1950s, Mr. Wiesel submitted the manuscript for publication in France. Publisher after publisher turned him away. Les Éditions de Minuit published the manuscript in 1958, but the book found little commercial success.

Initially, it fared no better in the United States. One rejection note, from Scribner’s, called the work a “horrifying and extremely moving document” but cited “certain misgivings as to the size of the American market” for it, according to a New York Times account of the book’s publication. Critics wrote admiring reviews when Hill & Wang published it in 1960, but few people in the general public knew that “Night” existed.

As time passed, more survivors began to open up about the war. Among the most prominent of them was Mr. Wiesel, who in the 1960s, by then living in the United States, began a celebrated lecture series at the 92nd Street Y in New York City.

Mr. Wiesel, whose speeches routinely drew sell-out crowds, would remain highly sought-after as a lecturer for the rest of his life. More than lecture, he told stories, one flowing into the next in a way that recalled a passage from Ecclesiastes, the one that inspired the titles of his two-volume memoir: “All Rivers Run to the Sea” and “And the Sea Is Never Full.”

(…)

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter appointed Mr. Wiesel chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust, which would call for the creation of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. It was an important recognition of his role in the Holocaust community.

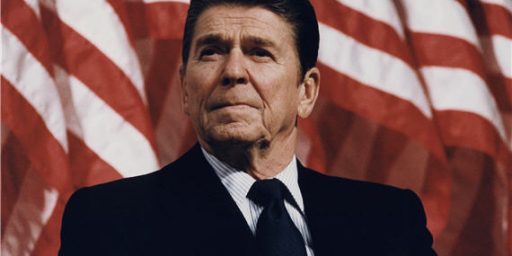

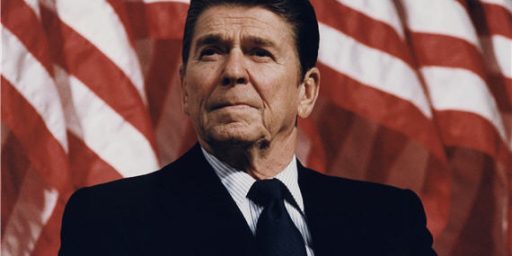

Another turning point came in 1985, when Mr. Wiesel publicly confronted President Ronald Reagan about a coming trip to Germany, where the president planned to visit the Bitburg military cemetery. Mr. Wiesel and others opposed the trip after learning that the cemetery included the graves of several dozen members of the S.S., the elite Nazi force.

“That place, Mr. President, is not your place,” Mr. Wiesel said during a White House ceremony in which Reagan awarded him the Congressional Gold Medal, Congress’s highest civilian honor. “Your place is with the victims of the S.S.”

Several weeks later, amid controversy, Reagan made the trip to Bitburg.

It was not the last time Mr. Wiesel took on a head of state. In 1986, just after Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish year, he learned he had been selected for the Nobel Peace Prize. He said the honor did not make him a different person — “If the war did not change me, you think anything else will change me?” he commented upon winning the prize, the Times reported — but it did confer on him considerably greater authority.

Speaking at the dedication of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1993, Mr. Wiesel faced President Bill Clinton and said: “Mr. President, I must tell you something. I have been in the former Yugoslavia last fall. I cannot sleep since what I have seen. As a Jew I am saying that. We must do something to stop the bloodshed in that country.”

Clinton later told reporters that he accepted Mr. Wiesel’s challenge, The Washington Post reported. The president went on to lead NATO in two bombing campaigns in the Balkans, first in 1995 against Bosnian Serbs and four years later to stop ethnic cleansing in Kosovo.

Later in Clinton’s administration, Mr. Wiesel challenged him about the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

(…)

Mr. Wiesel compared apartheid to anti-Semitism and backed the Solidarity movement in Poland. He spoke out on behalf of Soviet Jews, Cambodians and the Kurds, among other populations. He declared his support for the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, maintaining that the United States has an obligation to intercede when evil comes to power.

Critics accused Mr. Wiesel of having a blind spot where Israel was involved. When talk show host Oprah Winfrey asked him in an interview whether he had any regrets, he responded: “I wish I had done more for the Palestinian refugees. I regret that.”

Speaking about the Holocaust, he often emphasized his conviction that it was an unparalleled event in history.

“I have learned that the Holocaust was a unique and uniquely Jewish event, albeit with universal implications,” he said at the White House speech in which he prevailed on Reagan not to visit the Bitburg cemetery. “Not all victims were Jews, but all Jews were victims.”

(…)

Eliezer Wiesel was born Sept. 30, 1928, in Sighet, a town in modern-day Romania that he would later describe as a “Chagall-style Jewish city” in the Carpathian Mountains.

Mr. Wiesel grew up in a tightknit, observantly Jewish family, the only son of a grocer, Shlomo, and his wife, Sarah. So great was the boy’s religious fervor, instilled in him by his Hasidic grandfather, that he wept in prayer at the synagogue. He became a rapt student of the Jewish mystics, who taught that meaning could be deciphered from numbers.

Mr. Wiesel was 15 years old, a new arrival to Block 17 at Auschwitz after being swept up in the last transport from the Sighet ghetto, when the number A-7713 was tattooed on his left arm. He said that when he turned 18, he wasn’t really 18, the camps having turned him prematurely into an old man.

After his liberation from Buchenwald, Mr. Wiesel found himself on a train of orphans that ended up in France. Unbeknownst to him, his two older sisters had survived. The siblings were reunited after one of the girls, also living in France, spotted her brother’s face in a newspaper.

In his Nobel lecture, Mr. Wiesel recalled those early years after his liberation:

“The time: After the war. The place: Paris. A young man struggles to readjust to life. . . . He is alone. On the verge of despair. And yet he does not give up. On the contrary, he strives to find a place among the living. He acquires a new language. He makes a few friends who, like himself, believe that the memory of evil will serve as a shield against evil; that the memory of death will serve as a shield against death. This he must believe in order to go on.”

Mr. Wiesel’s new language, and the one in which he would do much of his writing for the rest of his life, was French. He absorbed the existentialist works of Sartre and Camus and supported himself as a choir director while studying at the Sorbonne. Mr. Wiesel was later hired as a foreign correspondent for an Israeli newspaper; the job proved pivotal when it led him to Mauriac.

In 1956, he immigrated to the United States, becoming an American citizen and working for what was then called the Jewish Daily Forward. Journalism would remain his livelihood for years after the war, but he would ultimately pursue a life of teaching and writing books. He once wryly summed up the nature of reporting:

“I realized that I spent my entire life using maybe 400 or 500 words,” he told Salon in 2000. “All I had to do was change the names. Sometimes this person said, sometimes another person said. But the word ‘said’ remained. And I said I don’t want to live like that.”

Mr. Wiesel taught for more than 30 years at Boston University, where his classes were blockbusters. At Yale University, where he was a visiting professor in 1982, 350 students signed up for 65 spots in his course on literature and memory.

(…)

“I had a feeling he was talking mysticism to me,” Mr. Wiesel was said to have remarked, referring to the baseball commissioner.

Mr. Wiesel declined, telling the commissioner that the game took place on the Sabbath and that the next one fell on a holy day. The commissioner cleverly took the matter to some rabbis, who said that after sunset Mr. Wiesel would be permitted to participate. So Mr. Wiesel finally agreed, but only after consulting his then-teenage son, a baseball fan.

Mr. Wiesel often said that he found hope in the young, in both his students and his own child.

“When Marion, my wife, told me she was pregnant, my first feeling was fear,” he told the Times. “The world is not worthy of children. I was frantic. But the next wave was joy. Will it be a boy or a girl? Whose name will it have — my mother’s or my father’s?”

His son Shlomo Elisha Wiesel survives him, as does his wife, the former Marion Erster Rose, a Holocaust survivor whom he married in 1969. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

Additional obituaries on Wiesel’s life are available from The New York Times, The Jerusalem Post, and Haaretz.

There’s very little that can be said about a man like Wiesel that can’t be better expressed by his own words, and in that regard I can highly recommend at least reading “Night,” his account of being taken with his family to, and surviving, the Auschwitz-Buchenwald concentration camps. It is a chilling, emotional tale of one of the most horrifying times in human history through the eyes of a young boy and, along with all of the other accounts from survivors that have been cataloged since the end of World War Two, it stands as a reminder of what the Holocaust was and why it can never be forgotten or minimized, something that becomes even more important as old age takes the last of the survivor’s generation from us. After everything that happened, it would be tragic if history ever came to forget, or to minimize what Wiesel and his fellow survivors endured, and we owe it to them to never forget, and to make sure it never happens again.

What was perhaps most remarkable about Wiesel was the fact that, despite what he went through, he did not emerge from the hell on earth of the Holocaust resentful or bitter. Instead, he came across in public as determined to share the story of the Holocaust and to be a witness and advocate for human rights around the world. Even during those times when he was being critical, such a when he attempted to publicly persuade President Reagan not to visit a German military cemetery that included the graves of members of the Waffen SS, he did so in a manner that didn’t come across as angry or resentful, something that made his words all the more powerful. And the fact that that he used the moral authority that being a witness to and survivor of horror gave him to advocate for others, whether in South Africa, Bosnia, or Rwanda, only increased his prominence.

For all he endured, Wiesel ended up giving back to a world that once turned its back on his people and for that he deserves to be lauded. Elie Wiesel suffered through unspeakable evil and emerged to become a witness for truth and human rights, there’s really not much better one can ask out of one life.

To celebrate Donald Trump put out a grossly anti-semitic Tweet.

Endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan, gleefully adopted by Stormfront and their ilk, Trump, despite having a Jewish convert wife, slaps a big red Star of David over pictures of money and Hillary.

Please, won’t someone tell me again how evil Hillary is with her email server? Anyone?

A remarkable man, moral, humane, and a witness to history. Resquiat in pace.

He lived a long and great life and every moment of it was a repudiation of everything the Nazis stood for.

He was a great man who did everything in his power to ensure that there wouldn’t be a repeat of the Holocaust, and to shine a light on the garden variety genocide that happens on a disturbingly regular basis.

People of this caliber don’t come around often enough.

I do wish I liked his books, though.

Wiesel contributed the testimony of his heart and soul. None of us can apprehend the whole story of humanity; its greatness, the depths of evil acts, and even the quotidian lives of everyday people are a mystery that we must approach with awe and humility. Wiesel drew back the curtain on great evils and in doing so showed us a bit of the road to endurance and resilience. A long life with affirmative contributions to humanity; there is nothing more one can ask for.

May his closest be comforted as we wish comfort to all who mourn.

Never Forget.

Never Again.

I recommend the last few minutes of his 2012 talk before the Public Counsel group. https://youtu.be/_lJ-8wx-MBo

May we all not sleep well in the face of suffering and may his memory be a blessing and a comfort.

@michael reynolds:

Correction: It is Trump’s daughter, not his wife, who is a Jewish convert. And she isn’t estranged from her dad but apparently quite close to him, and she and her husband, a New Yorker who was born and raised Jewish, are a major part of his campaign. How they live with themselves, I have no idea.

@michael reynolds: the need to invoke “trump” into everything in here is getting old but it’s expected.

his son in law is jewish and his daughter is a jewish convert. and last i checked, they don’t hate him…..

@bill: It’s already been conclusively demonstrated that the graphic originated on a neo-Nazi site. There simply is no question the graphic was deliberately designed with an anti-Semitic message. Now, that doesn’t automatically prove that whoever in the Trump team posted this graphic realized its implications. But this isn’t the first time the Trump campaign has lifted material from white nationalists, and what’s especially damning is that they have refused to disavow it; instead, the campaign is taking the absurd position that a graphic which unquestionably had an anti-Semitic source did not have an anti-Semitic intent.

As for politicizing this thread, please. I can state with a fair amount of confidence that had Wiesel lived a while longer, he would have condemned the tweet. While he never publicly expressed partisan preferences as far as I’m aware, he did occasionally criticize candidates for much milder transgressions. (For example, in 2012 he called upon Mitt Romney to denounce the Mormon practice of posthumous baptism. I disagreed with Wiesel on this.) To anyone who went through Wiesel’s experiences and lived to the present day, it would be extremely disturbing to see the presidential candidate of a major party in the USA passing along a graphic reminiscent of the old Nazi propaganda cartoons.

@Kylopod:

Really? Why?

@SKI: You’re asking why I’m not offended by the LDS “baptism of the dead”? Well, to start with, it has no real effect on anyone. Sure it’s silly, but it’s about the most benign interpretation of Christian salvation doctrine I’ve ever heard of. They’re actually rejecting the mainstream Christian belief that people who go to their grave without accepting Christ are doomed to eternal hellfire. They’re not launching pogroms against nonbelievers. They’re not going door to door…well actually they are, but at least they have an insurance policy for those they don’t reach.

So why should I care if they claim to have “converted” hoards of long-dead people they’ve never met from Maimonides to Irving Berlin? They believe what they believe, no one gets harmed in any tangible way, and meanwhile they’ve got a much more optimistic view of these individuals’ fate than a lot of so-called “normal” Christians do.

And did I mention that it’s inspired them to create one of the most extensive and useful genealogical databases in the world?

Furthermore, I don’t think Mitt Romney or any other Mormon who happens to run for president should be placed in the position of having to specifically comment on every illiberal or controversial belief propounded by their Church. It strikes me as skirting dangerously close to the criticisms of JFK in 1960 or Obama in 2008, and it’s something you never hear of candidates whose sects are regarded as safe and mainstream, such as Southern Baptists. At some point, you’ve got to let a candidate’s views speak for themselves.

@Kylopod:

And I guess that is where I strongly disagree. As someone who lost family in the Shoah precisely because they were Jewish, the Mormon Church actively seeking out to convert them from Judaism is hurtful and offensive. And did and does have a “real effect” on people – including Elie Wiesel.

Now you clearly aren’t hurt by this and, just as obviously, think no one else should be but you don’t get to decide whether or not other’s actual real feelings are valid. You can choose to disregard them but you can’t decide they don’t exist.

@SKI: I, too, have family that perished in the Holocaust. My mother’s parents are survivors (my grandmother, about five years older than Wiesel, is still alive and lives in the Upper East Side). There probably is a generational element to our attitudes. I was born in the late 1970s, and the Jews I’ve talked to around my age or younger or even slightly older tend to agree with me about the LDS doctrine. I suppose to those from the Holocaust generation and especially to the survivors themselves, any trace of Christian intolerance toward the Jewish faith looks like simply the beginning of a road leading inexorably toward pogroms, expulsions, and genocide. But to younger American Jews for whom the major acts of anti-Semitic violence in the world come from sources other than Christian missionaries, these things are a lot less likely to bother us. The Trump graphic is disturbing not because it hurts our feelings but because it is implicitly a threat. We are not going to lose sleep over a weird Mormon doctrine that by definition is a device for leaving us alone.

I was born in the early ’70’s so I’m not all that much older.

And my feelings aren’t paranoia-driven by the fear of a slippery slop towards pogroms, expulsions, and genocide. But feel free to condescend a bit more…

Seriously, you do not get to say that my feelings, or Wiesel’s, or much of the freaking community aren’t valid. I’m not worried about antisemitism in the LDS actions. I’m pissed off at their hubris and inappropriateness. There is a reason they backed down and stopped the practice.