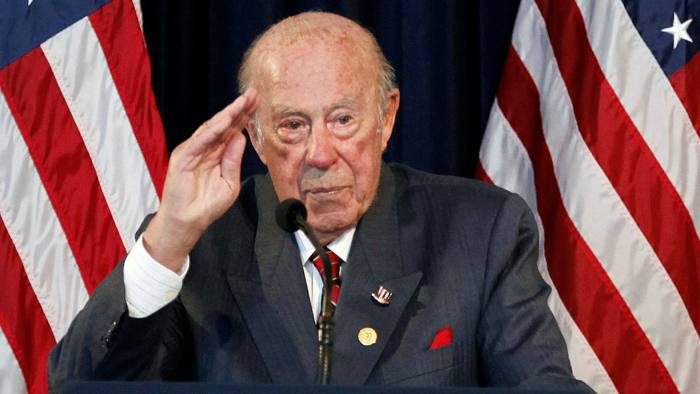

George Shultz, 1920-2021

The longtime public servant has died, aged 100.

Washington Post (“George P. Shultz, counsel and Cabinet member for two Republican presidents, dies at 100“):

Mr. Shultz, one of only two people to hold four Cabinet positions in the U.S. government and as secretary of state was an essential participant in Reagan’s negotiations with the Soviet Union, died Feb. 6 at his home in Stanford, Calif. He was 100. The Hoover Institution at Stanford University, where Mr. Shultz was the Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Distinguished Fellow, confirmed the death but did not provide details.

Mr. Shultz was a policy maven, conservative but curious, patient and determined. He ranged widely over domestic and foreign affairs. “He was a doer, and not a talker,” former secretary of state James A. Baker III said Sunday. “He was plodding and calm, thoughtful and rational. He was not at all flamboyant.”

Mr. Shultz served as director of the Office of Management and Budget, labor secretary, treasury secretary and secretary of state. Only Elliot Richardson had held more Cabinet posts. Mr. Shultz taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Chicago and Stanford, where at his death he was emeritus professor at the Graduate School of Business. He also was president of Bechtel, the multinational construction and engineering firm, for eight years.

When selected to replace retired Gen. Alexander M. Haig Jr. as Reagan’s secretary of state in 1982, Mr. Shultz saw that relations between the United States and the Soviet Union had sunk into deep cold after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and a Soviet-backed crackdown in Poland. Reagan promised in his 1980 campaign for president to confront the Soviet Union more directly, and in his first two years had embarked on a more aggressive posture, including a military buildup. “Relations between the two superpowers were not simply bad; they were virtually nonexistent,” Mr. Shultz recalled in his memoirs.

[…]

Mr. Shultz brooded over the worsening situation and what to do about it. When he met the president for an informal dinner at the White House, talkative and relaxed, Reagan told Shultz of his abhorrence of mutually assured destruction, the cocked-pistols approach that defined the superpower nuclear standoff. This insight into Reagan’s thinking helped guide Mr. Shultz toward change, which was also aided by the ascension of Gorbachev as the Soviet leader in March 1985.

Hard-liners in the U.S. government continued to cast a critical eye on Moscow, but Mr. Shultz saw Gorbachev as someone, as British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had said, whom “we can do business with.” Shultz had to constantly do battle with others in the administration. “No one in the arms control community shared Reagan’s view” about eliminating nuclear weapons, Mr. Shultz later recalled. He told aides, “This is his instinct and his belief. The president has noticed that no one pays any attention to him.”

Mr. Shultz’s efforts to change course brought him into conflict with CIA Director William Casey and Defense Secretary Caspar W. Weinberger, among others. “The hardliners were always attacking both of us,” recalled Baker, who described Mr. Shultz as a mentor. “He had my back, and I had his.”

[…]

George Pratt Shultz was born in Manhattan on Dec. 13, 1920. An only child, he was raised in Englewood, N.J., and attended the private Loomis School in Windsor, Conn. His father, Birl, was dean of the educational institute of the New York Stock Exchange, a training school for employees of the exchange.

He graduated from Princeton University in 1942 with a bachelor’s degree in economics and played on the varsity basketball and football teams. After service in the Marine Corps in the Pacific during World War II, he received a doctorate in industrial economics in 1949 from MIT. (He reportedly had a tattoo of a tiger, the Princeton mascot, on his bottom, although he steadfastly refused to confirm it.)

New York Times (“George P. Shultz, Influential Cabinet Official Under Nixon and Reagan, Dies at 100“):

George P. Shultz, who presided with a steady hand over the beginning of the end of the Cold War as President Ronald Reagan’s often embattled secretary of state, died on Saturday at his home in Stanford, Calif. He was 100.

[…]

Mr. Shultz, who had served Republican presidents since Dwight D. Eisenhower, moved to California after leaving Washington in January 1989. He continued writing and speaking on issues ranging from nuclear weapons to climate change into his late 90s, expressing concern about America’s direction.

“Right now we’re not leading the world,” he told an interviewer in March 2020. “We’re withdrawing from it.”

He carried a weighty résumé into the Reagan White House, with stints as secretary of labor, budget director and secretary of the Treasury under President Richard M. Nixon. He had emerged from the wars of Watergate with his reputation unscathed, having shown a respect for the rule of law all too rare in that era. At the helm of the Treasury, he had drawn Nixon’s wrath for resisting the president’s demands to use the Internal Revenue Service as a weapon against the president’s political enemies.

As secretary of state for six and a half years, Mr. Shultz was widely regarded as a voice of reason in the Reagan administration as it tore itself asunder over the conduct of American foreign policy. He described those struggles as “a kind of guerrilla warfare,” a fierce and ceaseless combat among the leaders of national security.

He fought “a battle royal” in his quest to get out the facts, as he later testified to Congress during the Iran-contra affair. The director of the Central Intelligence Agency, William J. Casey, followed his own foreign policy in secret, and the State Department and the Pentagon constantly clashed over the use of American military force. Estranged from the White House, Mr. Shultz threatened to resign three times.

Mr. Shultz was summoned to Camp David and handed the wheel of American foreign policy in June 1982. Initially deemed too politically moderate by Reagan’s advisers, he had been passed over for the post of secretary of state the previous year. (The position had gone to Alexander M. Haig Jr., the mercurial and combative general who lasted barely 18 months before he abruptly left office amid fierce disputes over the direction of diplomacy and the projection of American power.)

The Middle East was exploding, the United States was underwriting covert warfare in Central America, and relations with the Soviet Union were at rock bottom when Mr. Shultz became the 60th secretary of state.

Moscow and Washington had not spoken for years; nuclear tensions escalated and hit a peak during his first months in office. The hard work of replacing fear and hatred with a measure of trust and confidence took place in more than 30 meetings with Mr. Shultz and the Soviet foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, between 1985 and 1988. The Soviets saw Mr. Shultz as their key interlocutor; in private, they called him the prime minister of the United States.

Continuous meetings between Mr. Shultz and Mr. Shevardnadze helped ease the tensions between the superpowers and paved the way for the most sweeping arms control agreement of the Cold War, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Ratified in June 1988, it banned land-based ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and missile launchers with ranges of up to 3,420 miles. Within three years the two nations had eliminated 2,692 missiles and started a decade of verification inspections.

The treaty remained in force until August 2019, when President Donald J. Trump scrapped it, contending that Russia had broken the accord by developing a new cruise missile.

Almost alone among the members of the Reagan team, Mr. Shultz had seen early on that the new Soviet leader, Mikhail S. Gorbachev, and his allies in Moscow were different from their predecessors. The rest of the national security team, and especially Reagan’s defense secretary, Caspar W. Weinberger (known as Cap), had scoffed at the idea that the Kremlin could change its tune.

“Many people in Washington said: ‘There is nothing different, these are just personalities. Nothing can be changed,'” Mr. Shultz recounted in an oral history of the Reagan administration. “That was the C.I.A. view; that was Cap’s view; that was the view of all the hard-liners.”

“They were terribly wrong,” he added.

His successor and protegee, Condoleezza Rice, remembers him in a Washington Post encomium entitled “George Shultz will be remembered as one of the most influential secretaries of state in our history.”

“It is the best job in government.” I had just called to tell George Shultz that I had been nominated to be secretary of state. I wanted to hear from my mentor, friend and soon to be predecessor. But then he quickly corrected himself. “Except for when I was a captain in the Marine Corps.”

That was quintessentially George. He loved his country and loved serving it — whether on the battlefields of World War II or the gilded rooms of diplomacy in foreign capitals around the world.

George will be remembered as one of the most influential secretaries of state in our history. He was President Ronald Reagan’s most trusted adviser as the Cold War was drawing to a close. His deft touch in reading and encouraging Reagan’s instincts, first to challenge the Soviet Union, and then to find common ground through diplomacy, served the president and the country well.

[…]

As secretary, he greatly influenced policy in the Middle East, even though the bombing of the Marines in Lebanon in 1983 haunted him, personally, throughout his life. And just a few years after the establishment of relations with the People’s Republic of China, many credit George with laying down a path for regular and successful diplomacy with Beijing on everything from trade to human rights. Diplomats knew him as a good listener and a practical man. His favorite tactic was to say to his counterpart, “You write down what worries you and I will do the same, and then we will work our way down the list.” And yet, he never lost sight of the centrality of freedom to the human experience and to human dignity. His integrity was unquestioned by friend and foe alike.

Even if secretary of state was his “best job” in the Cabinet, he will also be remembered for his work as treasury secretary and director of the Office of Management and Budget where his belief in the power of markets made him a force with two presidents. Yet, when one spent just a little time with George, he would turn to a set of achievements that were core to him. He was immensely proud of his work in civil rights and equal opportunity — as secretary of labor for Richard Nixon.

George remained seized with questions of equality at home, particularly in education. That concern led him to champion K-12 school reform and parental choice and — with his wife, Charlotte — to single-handedly save an inner-city school in Palo Alto, Calif., that needed funding to survive. Too few people knew that side of George. He just went about that work. He believed deeply that the United States could lead with moral authority abroad only if it was true to its values at home.

In 100 well-lived years, George made an impact in corporate, academic and governmental institutions. He did so by deed but also by imparting lessons that we could all apply when we were called to lead. “Be sure to garden,” he would say, insisting that relationships — particularly with allies — were like flowers in a garden and needed constant tending.

“Never point your weapon unless you intend to fire it,” he would say, recalling what his master sergeant had said to the young Marine. That was an admonition to be careful with threats and “red-lines” that you could not or would not enforce.

Shultz was a giant figure at a time when my interest in world affairs was beginning. I was about to begin my sophomore year in high school when he was sworn in as Secretary of State. I was vaguely aware that he had held previous cabinet positions but I’m not sure I realized he had a brilliant academic career in between.

He came to speak to our university two or three years ago and, while clearly no longer at the peak of health, remained remarkably lucid for a man of such advanced years. That he retired from public office, handing over the reins at Foggy Bottom to James Baker, more than three decades ago —having just turned 68—is rather astounding.

Having a few years on you Prof J, I recall Shultz as Nixon’s, Sec of Labor and advocating policies that Bernie and AOC would be comfortable with.

Since the 70’s and 80’s were dominated by R presidencies, it isn’t a surprise that the statesmen of that time are dominated by Republicans. But comparing those who served America under Nixon/Ford/Reagan/Bush41 and those who served Bush43/Trump leaves no doubt that the Republican party is intellectually bereft.

George Shultz served his country well and honorably. RIP

No mention at all about his role in the rise (and maybe the fall) of Theranos.

To be fair, he was merely a big member in the board, who recruited other big names, but not the prime mover in the scam. His grandson was one of the whistle blowers, and he supported him against Theranos and Holmes. So there’s that.

Perhaps the ultimate ‘old pro.’

@Sleeping Dog: I was alive for the Nixon presidency but not old enough to understand it. I read a ton on Watergate in late high school/early college and quite a bit on the opening to China and other foreign policy decisions as a grad student and later. But, yes, it’s arguable that Nixon was the most liberal domestic politician since LBJ, with Obama being the only real contender.

@Michael Reynolds: Along with Jim Baker, he really epitomized that concept, at least in GOP circles. The Dems didn’t have the presidency that often in that era and the country has operated on a more partisan basis since, so there are no great candidates from the Clinton-Obama-Biden era even though there was a lot of comparable talent.

As a young enlisted Airman, I was deployed to an airfield in Honduras when George Shultz passed through in 1988. As he was rumored to have been critical of Iran-Contra I always wondered how he felt about transferring through that airfield where two aircraft of the alleged Ollie’s Air Force appeared to have ended up. There was a C-7 Caribou with the tail number 3, and a C-123 Provider with the tail number 5, both were located on the “Honduran” ramp. According to Honduran enlisted folks the two aircraft had shown up shortly after the C-123 Eugene Hasenfus had been on was shot down over Nicaragua in 1986.

Maybe there was no connection, but it was enough to convince me at the time that Reagan and friends had been less than honest about the whole Iran-Contra endeavor.

@Kathy: raoul

From what I read Schultz’ support of his grandson on the Theranos matter was tepid but I have yet to read Bad Blood.

@Raoul:

I read the rather haphazard and informal memoir of the period written by the younger Schultz. I wouldn’t be surprised if he overstated his grandfather’s support. He does mention it didn’t come automatically, but that he had to persuade him something screwy was going on.

@Raoul: @James Joyner:Not to be snarky but how is the Obama presidency liberal? The AHCA is as a conservative approach as any regarding healthcare, the next step of doing nothing. In fact I would suggest that he was the most centrist president ever, every position was calibrated to its level of popular support from gay rights to fiscal governance. Please share what you think are positions Obama took that are left of the median voter.

The contrast with what passes for credentials in more recent administrations could not be more striking.

@Raoul: Tan suits, fancy mustard, and anticolonialism, of course. And the belief that a black man could be president.

Seriously, though, while he may not have been to the left of the average American, he was to the left of the average American voter, and far to the left of the political establishment. He brought things into policy that had been slowly becoming the cultural expectation in the previous two decades.

As our first black President, he had to be very cautious, lest he inspire an insane racist backlash that would result in his successor being a deranged buffoon who appeals to white nationalists terrified that they might have to share power with those people.

Biden pushed him to the left a few times with his “gaffes”, most notably on marriage equality. I wonder what would have happened had we gotten a more-lefty but white-male nominee in 2008. Obama’s presidency was transformative, but looking at what America has transformed into… I’m not sure that’s a good thing.

@Gustopher: Correct, I am of the firm belief that Obama’s race actually reigned him precisely because he was the first black president.

@DrDaveT:

The Dems are more likely to go for wonks than Republicans nowadays but there are still a lot of highly-credentialed folks in DC. Hell, even Trump had people like Mark Esper (West Point undergrad; MPA from Harvard Kennedy School; PhD George Washington) and HR McMaster (West Point; Duke PhD). The Biden administration is lousy with Ivy League lawyers and high-powered graduate degrees.

(Not to mention that Shultz got his PhD back in the day when it took 3 years, comparable to a law degree, rather than the 5-7 that’s more typical today.)