Gorsuch and Kavanaugh are Different Justices So Far

Despite similar paths to the Supreme Court, it turns out the two don't share the same style and approach.

Adam Liptak brings us the shocking news that the two Trump appointees to the Supreme Court are not exactly the same person and may even have minds of their own.

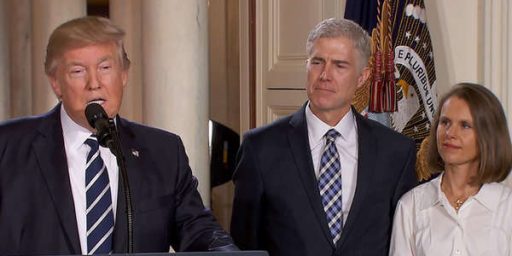

President Trump’s two Supreme Court appointees went to the same Jesuit high school in the Washington suburbs — at the same time. After attending Ivy League colleges and law schools, they worked as law clerks on the Supreme Court — for the same justice, in the same term.

They served as appeals court judges for more than a decade, turning out opinions that captured the attention of conservative legal groups like the Federalist Society and the Heritage Foundation. They were confirmed by tight votes, mostly along party lines.

On the Supreme Court, they were widely expected to be jurisprudential twins. But it turns out that there is more than a little daylight between Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, who joined the court in 2017, and Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, who started in October after facing accusations of sexual assault, which he denied, at his confirmation hearings.

“They’re disagreeing more than we would have expected,” said Jonathan H. Adler, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University. The two justices have found themselves on opposite sides in quite a few cases, including ones involving the death penalty, criminal defendants’ rights and Planned Parenthood.

—NYT, “Kavanaugh and Gorsuch, Justices With Much in Common, Take Different Paths“

So, on the one hand, this is good news. Given the politically fraught processes that led to their being seated, there has been a completely understandable fear that Gorsuch and, especially, Kavanaugh would be reliable Republican votes, if not rubber stamps for the Trump administration. Thus far, that hasn’t been the case. On the other hand, we’re not even through Kavanaugh’s first term. We may simply not have enough data from which to draw meaningful conclusions.

Both justices lean right, but they are revealing themselves to be different kinds of conservatives. Justice Gorsuch has a folksy demeanor and a flashy writing style, and he tends to vote with Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr., the court’s most conservative members.

Justice Kavanaugh is, for now at least, more cautious and workmanlike. He has been in the majority more often than any other justice so far this term, often allied with Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., who is at the ideological center of the current court.

The two justices also have differing personal styles, said Elizabeth B. Wydra, the president of the Constitutional Accountability Center, a liberal group. “Gorsuch came on strong — some might say too strong — when he first joined the court, staking out his positions and finding a distinct voice quickly,” she said. “Kavanaugh has kept a lower profile among his fellow justices, perhaps reflecting the cloud under which he joined the court.”

Justice Kavanaugh has not yet completed a full term, and the court’s biggest decisions — on religious monuments, partisan gerrymandering and adding a citizenship question to the census — are yet to come. Neither of the newest justices is likely to disappoint his conservative supporters in those blockbuster cases.

Now, again, one might have predicted the opposite. Given his hyper-partisan bluster during his confirmation hearings, one might have guessed Kavanaugh would be a bull in a china shop. But the embarrassing nature of the process, including credible allegations of sexual assault and drunken debauchery, might have him temporarily chastened and lying low.

But there is more to the Supreme Court’s work than the handful of big decisions issued at the end of June. It must also decide which cases to hear, how broadly to decide them and on what basis. In all three areas, the two justices appointed by Mr. Trump have taken different paths, with Justice Gorsuch for now veering further to the right.

There was little reason to predict those differences when the two men served as law clerks to Justice Anthony M. Kennedy starting in the summer of 1993. “We were in the middle of everything,” Justice Kavanaugh said in a 2017 interview, when he was still an appeals court judge.The two clerks had already known each other for more than a decade, having attended Georgetown Preparatory School in North Bethesda, Md., together. Justice Kavanaugh, now 54, was in the class of 1983. Justice Gorsuch, 51, was two years behind him.

As justices, though, the two men can be a study in contrasts. “Gorsuch is clearly more willing to sweep with a broader brush, appears less concerned about precedent and does not seem to have the same pragmatic streak that we see a little bit in Kavanaugh,” Professor Adler said.

Justice Gorsuch is a formalist who is committed to the interpretive tools of originalism, which looks to the meaning of the Constitution when it was adopted, and textualism, which focuses on statutory wording. He is suspicious of arguments grounded in pragmatism and impatient with lawyers who will not address him on his terms.

“We hear a lot about what makes sense in this room,” Justice Gorsuch said at an argument last month over whether a criminal statute was unconstitutionally vague. “I’m curious about what the law is.”

When he failed to get a satisfactory answer, he dismissed the lawyer. “Off you go,” he said.

That same day, in a statute of limitations case, Justice Kavanaugh indicated that he was inclined to take account of what makes sense. “If the law is murky and we can choose one path or another reasonably as a matter of law, wouldn’t we choose the more orderly, practical approach?” he asked.

Now this piece is interesting—and not what I would have expected.

First, while I’m inclined to look to the intent of those crafting the Constitution or statute in question, I agree with Kavanaugh that, if the law is murky, it’s perfectly reasonable to consider the practical effects of the ruling. Second, I’m not a fan of rudeness from the bench. “Off you go” is not something that should be coming from the mouth of a Supreme Court justice, unless it’s obvious in context that it’s jocular banter rather than dismissiveness.

There’s a lot more to Liptak’s piece, including getting into the weeds on the writing styles of the two men.

Again, we shouldn’t be surprised that two individuals, despite shared life experiences, are nonetheless individuals. But we should be relieved if it turns out that the two Trump appointees are in fact independent-minded judges who look at cases through their own judicial philosophies. Indeed, the long-term legitimacy of the Supreme Court as an institution depends on it.

I recall seeing Gorsuch’s yearbook as a comparison to Kavanaugh’s. It read like the yearbook of a nerd, with which I am well familiar. So I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that he would be more interested in principles and ideas. Or maybe a bit more rude. Kavanaugh seems more of a “go along to get along” kind of guy.

Reads more as a matter of style. On the big decisions we already know how they will vote. On less consequential matters they will occasionally differ. Not to get too paranoid, but have to wonder if this isn’t a bit like what we see in Congress where we see the Speaker or Senate leader let members vote against the party to maintain political viability when necessary. I think Roberts is pretty bright and concerned about the reputation of his court. He might be clever enough to encourage the new guy to run against type a bit, but only on minor issues.

Steve

One rubber-stamps with the left hand, the other rubber-stamps with the right. So different!

One might suspect Supreme Court Justices vote according to one’s individual interpretation of the law; they might vote their consciences, or along party lines, the nonintellectual vote. Either believing in laws in the way they were written, or believing that laws should change with the times, the ultimate decision remains with the Court. Notwithstanding, the difficulty with bending laws for the times is the moral equivalent of voting against righteousness, for the moral trajectory is pathetic. Politicizing the selection of Supreme Court Justices is a flawed process that has torn our nation’s people apart. It is a recent dilemma and is not what our founding fathers had imagined. Although the above article is somewhat premature, it will be interesting to read ten years from now.