Leonard Cohen, Legendary Singer, Songwriter, And Poet, Dead At 82

Another great loss for music in what has been a difficult year.

Leonard Cohen, the Canadian poet turned songwriter who came to have a reputation for songs that explored love, death, and faith, has died at the age of 82:

Leonard Cohen, the Canadian poet and novelist who abandoned a promising literary career to become one of the foremost songwriters of the contemporary era, has died, according to an announcement Thursday night on his Facebook page. He was 82.

Mr. Cohen’s record label, Sony Music, confirmed the death. No details were available on the cause. Adam Cohen, his son and producer, said: “My father passed away peacefully at his home in Los Angeles with the knowledge that he had completed what he felt was one of his greatest records. He was writing up until his last moments with his unique brand of humor.”

Over a musical career that spanned nearly five decades, Mr. Cohen wrote songs that addressed — in spare language that could be both oblique and telling — themes of love and faith, despair and exaltation, solitude and connection, war and politics. More than 2,000 recordings of his songs have been made, initially by the folk-pop singers who were his first champions, like Judy Collins and Tim Hardin, and later by performers from across the spectrum of popular music, among them U2, Aretha Franklin, R.E.M., Jeff Buckley, Trisha Yearwood and Elton John.

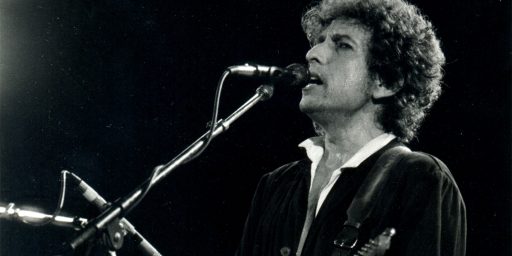

Mr. Cohen’s best-known song may well be “Hallelujah,” a majestic, meditative ballad infused with both religiosity and earthiness. It was written for a 1984 album that his record company rejected as insufficiently commercial and popularized a decade later by Jeff Buckley. Since then some 200 artists, from Bob Dylan to Justin Timberlake, have sung or recorded it. A book has been written about it, and it has been featured on the soundtracks of movies and television shows and sung at the Olympics and other public events. At the 2016 Emmy Awards, Tori Kelly sang “Hallelujah” for the annual “In Memoriam” segment recognizing recent deaths.

Mr. Cohen was an unlikely and reluctant pop star, if in fact he ever was one. He was 33 when his first record was released in 1967. He sang in an increasingly gravelly baritone. He played simple chords on acoustic guitar or a cheap keyboard. And he maintained a private, sometime ascetic image at odds with the Dionysian excesses associated with rock ‘n’ roll.

At some points, he was anything but prolific. He struggled for years to write some of his most celebrated songs, and he recorded just 14 studio albums in his career. Only the first qualified as a gold record in the United States for sales of 500,000 copies. But Mr. Cohen’s sophisticated, magnificently succinct lyrics, with their meditations on love sacred and profane, were widely admired by other artists and gave him a reputation as, to use the phrase his record company concocted for an advertising campaign in the early 1970s, “the master of erotic despair.”

Early in his career, enigmatic songs like “Suzanne” and “Bird on a Wire,” quickly covered by better-known performers, gave him visibility. “Suzanne” begins and ends as a portrait of a mysterious, fragile woman “wearing rags and feathers from Salvation Army counters,” but pauses in the middle verse to offer a melancholy view of the spiritual:

And Jesus was a sailor when he walked upon the water,

And he spent a long time watching from his lonely wooden tower,

And when he knew for certain only drowning men could see him,

He said “All men will be sailors then until the sea shall free them.”

But he himself was broken, long before the sky would open,

Forsaken, almost human, he sank beneath your wisdom like a stone.In 2008, Mr. Cohen was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which described him as “one of the few artists in the realm of popular music who can truly be called poets” and praised him for having “raised the songwriting bar.” In 2010, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, the Grammys’ group, gave him a lifetime achievement award, praising him for “a timeless legacy that has positively affected multiple generations.”

Wearing a bolo tie and his trademark fedora, Mr. Cohen dryly made light in his acceptance speech of the fact that none of his records had ever been honored at the Grammys. “As we make our way toward the finish line that some of us have already crossed, I never thought I’d get a Grammy Award,” he said. “In fact, I was always touched by the modesty of their interest.”

Leonard Norman Cohen was born in Montreal on Sept. 21, 1934, and grew up in the prosperous suburb of Westmount. His father, Nathan, whose family had emigrated to Canada from Poland, owned a successful clothing store; he died when Leonard was 9, but his will included a provision for a small trust fund, which later allowed his son to pursue his literary and musical ambitions. His mother, the former Masha Klonitzky, a nurse, was of Lithuanian descent and the daughter of a Talmudic scholar and rabbi. “I had a very messianic childhood,” Mr. Cohen would later say.

In 1951, Mr. Cohen was admitted to McGill University, Canada’s premier institution of higher learning, where he studied English. His first book of poetry, “Let Us Compare Mythologies,” was published in May 1956, while he was still an undergraduate. It was followed by “The Spice-Box of Earth” in 1961 and “Flowers for Hitler” in 1964. Other collections would appear sporadically throughout Mr. Cohen’s life, including the omnibus “Poems and Songs” in 2011.

A period of drift followed Mr. Cohen’s graduation from college. He enrolled in law school at McGill, then dropped out and moved to New York City, where he studied literature at Columbia University for a year before returning to Montreal. Eventually, after a sojourn in London, he ended up living in a house on the Greek island of Hydra, where he wrote a pair of novels: “The Favorite Game,” published in 1963, and “Beautiful Losers,” published in 1966.

“Beautiful Losers,” about a love triangle all of whose members are devotees of a 17th-century Mohawk Indian Roman Catholic saint, gained a cult following, which it retains, and eventually sold more than three million copies worldwide. But Mr. Cohen’s initial lack of commercial success was discouraging, and he turned to songwriting in hopes of expanding the audience for his poetry.

“I found it was very difficult to pay my grocery bill,” Mr. Cohen said in 1971, looking back at his situation just a few years earlier. “I’ve got beautiful reviews for all my books, and I’m very well thought of in the tiny circles that know me, but I’m really starving.”

Within months, Mr. Cohen had placed two songs, “Suzanne” and “Dress Rehearsal Rag,” on Judy Collins’s album “In My Life,” which also included the Lennon-McCartney title song and compositions by Bob Dylan, Randy Newman and Donovan. But he was extremely reluctant to take the next step and sing his songs himself.

“Leonard was naturally reserved and afraid to sing in public,” Ms. Collins wrote in her autobiography, “Sweet Judy Blue Eyes: My Life in Music” (2011). She recalled him telling her: “I can’t sing. I wouldn’t know what to do out there. I am not a performer.” He was “terrified,” she wrote, the first time she brought him onstage to sing with her, in the spring of 1967.

Later that year, after being signed to Columbia Records by John Hammond, the celebrated talent scout who also signed Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, Mr. Cohen released his first album. Its simple title, “Songs of Leonard Cohen,” and its cover, a portrait of the artist gazing solemnly into the camera, matched the music, which was spare and unembellished, in stark contrast to the psychedelic style that then prevailed.

The record began with “Suzanne,” which was already being performed by folk singers everywhere thanks to the popularity of Ms. Collins’s version. It also included three other songs of great impact that would become staples of Mr. Cohen’s live shows, and that numerous other artists would record over the years: “Sisters of Mercy,” “So Long Marianne” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye.”

His second album, “Songs From a Room,” released early in 1969, cemented his growing reputation as a songwriter. “The Story of Isaac,” a retelling of the biblical tale of Abraham and Isaac, became an anthem of opposition to the war in Vietnam, and “Bird on a Wire” went on to be recorded by performers including Joe Cocker, Aaron Neville, Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson.

In 1971, Mr. Cohen released “Songs of Love and Hate,” which contained the cryptic and frequently covered “Famous Blue Raincoat,” but after that his production began to tail off and his live performances became less frequent. He released three more albums during the 1970s but, amid bouts of depression, only two in the 1980s and one in the 1990s.

The quality of his songs remained high, however: In addition to “Hallelujah,” future standards like “Dance Me to the End of Love,” “First We Take Manhattan,” “Everybody Knows” and “Tower of Song” date from that era.

Mr. Cohen, raised Jewish and observant throughout his life, became interested in Zen Buddhism in the late 1970s and often visited the Mount Baldy monastery, east of Los Angeles. Around 1994, he abandoned his music career altogether and moved to the monastery, where he was ordained a Buddhist monk and became the personal assistant of Joshu Sasaki, the Rinzai Zen master who led the center, who died in 2014. He took the name Jikan, which means “silence.”

During the remainder of the decade, there was much speculation that Mr. Cohen, rather than merely taking a sabbatical, had stopped writing songs and would never record again. But in 2001, he released “Ten New Songs,” whose title suggests it was written while he was in the monastery. It was followed in 2004 by “Dear Heather,” an unusually upbeat album.

(…)

Mr. Cohen never married, though he had numerous liaisons and several long-term relationships, some of which he wrote about. His survivors include two children, Adam and Lorca, from his relationship with Suzanne Elrod, a photographer and artist who shot the cover of his 1973 album, “Live Songs,” and is pictured on the cover of his critically derided album “Death of a Ladies’ Man” (1977); and three grandchildren.

To the end, Mr. Cohen took a sardonic view of both his craft and the human condition. In “Tower of Song,” a staple of live shows in his later years, he brought the two together, making fun of being “born with the gift of a golden voice” and striking the same biblical tone apparent on his first album.

Now you can say that I’ve grown bitter, but of this you may be sure

The rich have got their channels in the bedrooms of the poor

And there’s a mighty judgment coming, but I may be wrong

You see, you hear these funny voices in the tower of song.“The changeless is what he’s been about since the beginning,” the writer Pico Iyer argued in the liner notes for the anthology “The Essential Leonard Cohen.” “Some of the other great pilgrims of song pass through philosophies and selves as if through the stations of the cross. With Cohen, one feels he knew who he was and where he was going from the beginning, and only digs deeper, deeper, deeper.”

More from The Washington Post:

Leonard Cohen, a Canadian-born poet, songwriter and singer, whose intensely personal lyrics exploring themes of love, faith, death and philosophical longing made him the ultimate cult artist, and whose enigmatic song “Hallelujah” became a celebratory anthem recorded by hundreds of artists, died Nov. 7. He was 82.

His death was confirmed by his biographer, Sylvie Simmons. Other details were not immediately available.

Mr. Cohen began his career as a well-regarded poet and novelist before stepping onto the stage as a performer in the 1960s. With his broodingly handsome looks and a deep, weathered voice that grew rougher and more expressive with the years, he cultivated an air of spiritual yearning mixed with smoldering eroticism.

Mr. Cohen never had a song in the Top 40, yet “Hallelujah” and several of his others, including “Suzanne,” “First We Take Manhattan” and “Bird on the Wire,” were recorded by performers as disparate as Nina Simone, R.E.M. and Johnny Cash. His lyrics were written with such grace and emotional depth that his songwriting was regarded as almost on the same level as that of Bob Dylan — including by Dylan himself.

Mr. Cohen was named to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2008, but his incantatory, half-spoken songs were more in the tradition of the European troubadour than the rock star. Lyrics were paramount to Mr. Cohen, but whether he was composing songs, poetry or fiction, there was always an underlying musical pulse.

All of my writing has guitars behind it,” he said, “even the novels.”

A character in Mr. Cohen’s 1963 novel “The Favorite Game” said, “I want to touch people like a magician, to change them or hurt them, leave my brand, make them beautiful.” In 1966, he published another novel, “Beautiful Losers,” that became a best seller.

The same year, after an informal audition at New York’s Chelsea Hotel, Mr. Cohen was signed as a singer-songwriter to Columbia Records by John Hammond, the talent scout who had promoted the careers of Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Dylan, Aretha Franklin and Bruce Springsteen.

At first Mr. Coehn was a reluctant performer. He often needed alcohol or drugs to go on stage early in his career. He labored over his songs, refining them as if he were polishing gems. He spent five years on “Hallelujah,” which appeared on his 1984 album “Various Positions” and is generally acknowledged as his masterpiece. Like much of his music, it took years to gain a popular foothold.

A 1994 recording by Jeff Buckley found a niche, and over time it was recorded by at least 300 artists. K.D. Lang’s performance of “Hallelujah” formed the centerpiece of the opening ceremonies of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

It was difficult for critics to explain exactly what made Mr. Cohen’s music so memorable and moving. The lyrics were poetic, of course, but his musical settings were ingenious, with shifting chords and deceptively simple melodies.

His music “was very intimate and personal,” singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega told the New Yorker. “Leonard’s songs were a combination of very real details and a sense of mystery, like prayers or spells,

Cohen never achieved the success in the United States that other artists such as Bob Dylan, to whom he was often compared, and when he did it was often the case that it was because one of his works, such as ‘Hallelujah’ was covered by another artist. Like many I’m sure, I became aware of who he was because of one of those covers, in my case it was the Jeff Buckley version of ‘Hallelujah,’ a complex song that draws on stories of David and Samson and other Biblical figures to create a powerful narrative that remains relevant to those days. Buckley’s version was used to masterful effect as the background music for what became one of the greatest scenes in the seven-year history of The West Wing from the third season finale episode ‘Posse Comitatus.’ Nonetheless, he was arguably on an equal to Dylan and those like him in terms of his songwriting, and his distinctive baritone, while not the perfect singing voice, gave voice in a unique way to his lyrics. He continued touring well into his later years and that voice, naturally, had less range but it also became deeper and that gave many of the later performances you’ll find on YouTube and elsewhere even more classic than the original recordings. As one of my friends remarked when this news was posted to Facebook last night, 2016 has been a devastating year when it comes to the loss truly great creators of music. Cohen’s death ranks right up there was with the loss of people such as Prince, Merle Haggard, Glenn Frey and David Bowie. The fact that not many people who will hear of his passing will know who he was or what he meant to the world of music is sad, but at least we’ll still have the recordings and the videos.

As with any musician, there’s only one way to really remember Cohen, though, and that’s through his music.

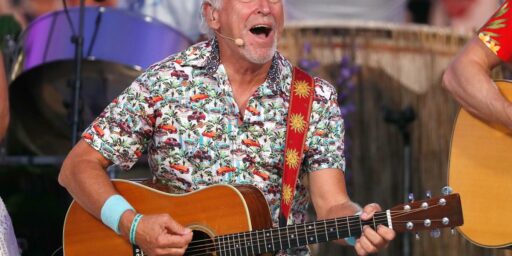

Here’s Cohen singing Hallelujah in a recording later in his career:

And here’s the Jeff Buckley version as it was used in The West Wing:

Back to Cohen, here he is singing ‘Suzanne’:

Anding finally, ‘I’m Your Man’:

Rest in peace.

My wife started crying when I was making dinner last night. I thought it was about the election, but it was Leonard Cohen’s passing.

Thank you for posting his obituary, Doug. He was in every way the opposite of Trump and a fine reminder that as bad as things may get in the USA over the next few years, humankind is capable of real beauty.

This bit deeper and harder than I’d expected for me. Leonard Cohen has never been at the center of my musical interests, but he has always been a compelling and intriguing figure. I suppose moreso than I had appreciated.

2016 keeps on going.

Seems like his songs have never been more appropriate.

Everybody knows that the boat is sinking;

Everybody knows that the captain lied;

Everybody’s got this broken feeling

That their mother or their dog just died.

@Hurling Dervish: The first time I heard “Everybody Knows” was in the mid-2000s on a college radio station in my area. The station played a lot of indie-rock, and at the time I’d heard several liberal-oriented anti-Bush anthems on this station. So I assumed the song I was hearing was yet another example of this genre. Where did I get this impression? Well, look at the first two verses:

Everybody knows that the dice are loaded

Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed

Everybody knows the war is over

Everybody knows the good guys lost

Everybody knows the fight was fixed

The poor stay poor, the rich get rich

That’s how it goes

Everybody knows

Everybody knows that the boat is leaking

Everybody knows that the captain lied

Everybody got this broken feeling

Like their father or their dog just died

Everybody talking to their pockets

Everybody wants a box of chocolates

And a long-stem rose

Everybody knows

My initial reaction was that this was a lot better than most of the Bush-bashing stuff I’d heard. I generally have not liked the protest music of the Bush years. Most of it is sanctimonious and inelegant, and compares poorly with equivalent stuff from the Vietnam era. There’s a pretty stark distance between “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and, say, “Seig Heil to the president gasman” from Green Day. But here finally, I thought, was an anti-Bush, anti-Iraq War screed that was actually deserving of comparison with its 1960s counterparts.

Of course, I soon looked it up and discovered the song was written in the 1980s. It’s been covered many times, most famously by Concrete Blonde in 1990 for the movie Pump Up the Music. And while that version is more polished than Cohen’s original (his low raspy voice is definitely an acquired taste), I love the original all the same.

Cohen’s music does something rare in popular music (aside from maybe rap), which is cause you to pay close attention to the lyrics. I’d say it’s even more so than Dylan (who in his later years has tended to sing incomprehensibly). He was the real deal.

Like most people, I bought a compilation CD of his back in college, listened to it a bit and then mostly forgot about it for the next twenty years. I was young and stupid and trying on new things and it didn’t really fit at the time.

But then, a few years ago, I heard “Slow” on the radio on my way into work, liked it a lot, and then listened to the rest of “Popular Problems” on Spotify when I got into the office. I was completely hooked. And from there, he’s quickly become a favorite of mine, even the stuff from that old compilation CD that I didn’t really have the patience for when I was younger.

This news is disappointing, to say the least. Every musician I really like these days seems to be either dying, dead or winning Nobel prizes.

We all have to die. We don’t all get to leave this much behind. He had the opportunity to contribute to civilization, and he did. He created beauty. He brought people peace and contemplation and joy. Is there anything more we can ask of any human being?

@michael reynolds: There was a beautiful profile of him in The New Yorker a few weeks back. He knew he’d be dying in the near future and he was perfectly content with that, having lived a good and interesting and productive life and being ready to share in the next experience we all must go through.

The New Yorker piece is exceptional. And his final album, released just last month, is amazing.

From the title track of that album: You Want It Darker

For those that don’t speak Hebrew, Hineni means “Here I am” and is what Abraham said to G-D when he was called. He was ready and he will be missed.