More Politicians for the Court

Norman Ornstein makes the interesting argument that a major reason the Supreme Court has been so divisive in recent years is that the old tradition of appointing experienced politicians to the bench has given way to the appointment of those with judicial experience.

More Politicians for the Court (WaPo, July 3, B7)

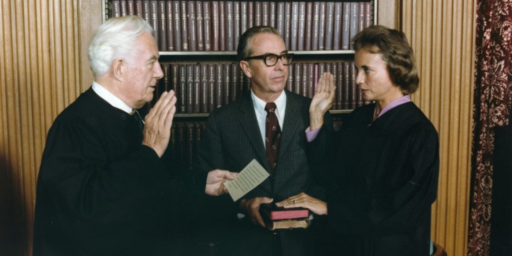

The resignation of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor means more than the loss of the most visible centrist on the Supreme Court. It also means the loss of the only justice who has been an elected politician. Before coming to the court in 1981, O’Connor had served in the Arizona Senate for five years, including time as majority leader.

Is that sort of experience important? Last year, at a remarkable seminar at Yale Law School, a group of former Supreme Court law clerks who served a half-century ago discussed the behind-the-scenes story of the 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. That decision actually took two years to reach. It was unanimous in the end, spanning the full range of ideology on the court from William O. Douglas on the left to Felix Frankfurter on the right. It could easily have been 5 to 4, given the issues at stake, the intensity of views and the breathtaking change the decision represented.

Frankly, if the current court had been serving back then, the decision probably would have been 5 to 4, like so many other highly charged and controversial decisions of recent years. What is the difference? The Warren Court in 1954 had five members who had been politicians — three former U.S. senators (one of whom had also been a mayor of Cleveland), one state legislator and a former governor, Chief Justice Earl Warren.

The former clerks talked about the way in which Warren, Justices Hugo Black, Sherman Minton, Frankfurter and others worked patiently to build consensus, not just a narrow majority. When it wasn’t forthcoming the first time the case was up, they put it off to the next year. Liberals and conservatives alike understood how important it was for society, and for the credibility of the court, to find that consensus and put forward a united front. The fact that several of them had been schooled in an environment of coalition-building — the legislative process — was a key to that sensitivity and to the final result.

There’s something to be said for this argument. I would note, though, that the nature of legislating in the 1960s and 1970s is substantially difference from what we’ve seen in the last ten or fifteen years, at least at the national level. Consensus-building and collegiality are hardly hallmarks of the modern U.S. Congress.

I would argue, too, that judges are not supposed to be legislators. Ornstein operates from the presumption that the Supreme Court exists to formulate public policy that is broadly accepted. Theoretically, however, their public policy role is merely to serve as referees to ensure that the elected politicians are operating within the rules of the game.

One can argue any point they want to bring up and pose any theory about the Supreme Court and as far as many citizens think, it would just be so many words. Credibility!!! Don’t make me laugh. The Supreme Court lost any credibility they had with their legislative decisions they have made over the past few years. For “seeing that the politicians operate within the rules” that is like the “pot calling the kettle black” The Supreme Court has shown that they are above the law and operate any way they want to, law or no law” The Supreme Court is just another UN in disguise

Let’s face it, there is only one answer to one question that every Senator is concerned about and that of course is the nominee’s position on abortion – bringing up stare decisis is just an indirect way of asking whether you are willing to overturn Roe/Casey et al. Asking whether you believe in the right to privacy is asking whether you are willing to overturn Roe/Casey; asking ….

Those speaking in favor of “moderate” judges are generally those who take it for granted that judges should be legislating. More here.