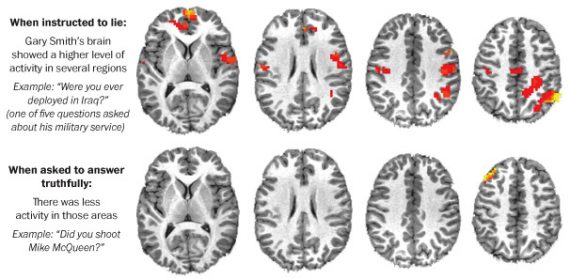

MRIs As Lie Detectors?

Will an MRI of your brain someday be able to tell if you're lying? And, if it can, should it be admissible in Court?

A murder case in Maryland is highlighting a new, and untested, use for MRI’s of a person’s brain that some are claiming could be the new lie detector:

Gary Smith says he didn’t kill his roommate. Montgomery County prosecutors say otherwise.

Can brain scans show whether he’s lying?

Smith is about to go on trial in the 2006 shooting death of fellow Army Ranger Michael McQueen. He has long said that McQueen committed suicide, but now he says he has cutting-edge science to back that up.

While technicians watched his brain during an MRI, Smith answered a series of questions, including: “Did you kill Michael McQueen?”

It may sound like science fiction. But some of the nation’s leading neuroscientists, who are using the same technology to study Alzheimer’s disease and memory, say it also can show — at least in the low-stakes environment of a laboratory — when someone is being deceptive.

Many experts doubt whether the technology is ready for the real world, and judges have kept it out of the courtroom.

Over three days, Montgomery County Circuit Court Judge Eric M. Johnson allowed pretrial testimony about what he called the “absolutely fascinating” issues involved, from the minutiae of brain analysis to the nature of truth and lies. But he decided jurors can’t see Smith’s MRI testing.

“There have been some discoveries that deception may be able to be detected,” Johnson said, but he added that there’s no consensus that the results can be trusted. “These are brilliant people, and they don’t agree.”

Still, researchers and legal experts say they can envision a time when such brain scans are used as lie detectors.

As the article goes on to note, though, the results of polygraph tests are generally not admissible for any purpose in a Court of law in any jurisdiction in the United States. The reason for this is two-fold. First, despite what one see on police and legal dramas, the science behind polygraphs is not at all settled, and there are any number of situations where false negatives or false positives can result. Someone who is innocent but subject to stress and panic attacks could give signals that a polygraph reader would interpret as indicative of lying, while someone who is guilty but a sociopath could lie through their teeth without the machine registering so much as a blip. Additionally, some medical conditions could cause the machine to give off false results. To the extent that the machine isn’t sufficiently reliable, general legal principles would require that results from the machine be barred from being admitted into evidence because they cannot be completely trusted, especially in a criminal case.

The second reason that a polygraph would be inadmissible is because of the extent to which its admission would serve to undermine the entire legal process. As a general rule, the trier of fact — the jury, or in the case of a bench trial, a judge — is considered to be the ultimate judge of the evidence and the testimony of witnesses, including the credibility of the witnesses. Allowing one side or the other to admit into evidence the results of a supposedly scientific test purporting to tell them whether or not a witness, or the Defendant, is telling the truth or not. The obvious danger, of course, is that juries would give undue weight to the results of this test as opposed to their own judgment of the credibility of the witnesses. In essence, by allowing evidence such as this into Court we’d be making the technology the judge of a Defendant’s guilt or innocence rather than the trier of fact. That would create a completely alien and, as noted above, unreliable legal system the results of which we can’t possibly imagine at this point.

It would appear that the situation is the same with brain scans:

[Assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California at San Diego Frank]Haist said the tests can’t conclusively determine when someone is being honest.

“The MRI is not a truth machine,” he said. “I can’t say with certainty that he is telling the truth.”

Other experts said the scans don’t prove whether Smith is being either deceptive or truthful.

New York University neuroscientist Liz Phelps told the court that there is “no evidence” that the scans are useful in revealing a “real-world, self-serving lie.”

Stanford neuroscience professor Anthony D. Wagner, called by prosecutors, said that “it’s premature” to use the tests in court. “I, personally, don’t know how the literature is going to play out in the long run. . . . I’m not concluding that it can never be shown,” he said.

(…)

Over more than a decade, researchers have devised a series of experiments using those scans to see what lying looks like inside the brain. A University of Pennsylvania study asked subjects to lie about holding a five of clubs. In another study, men in Hong Kong were shown images and asked to lie about their feelings about them. Accuracy rates for picking out the deceptions topped 90 percent in some cases.

Harvard Medical School assistant professor Giorgio Ganis hit 100 percent in a study that asked students to lie when they saw their birth date. “We probably got a little bit lucky,” Ganis said.

The Harvard birth-date experiment was cited by both sides as an example of the power the MRI might wield and its potential shortcomings.

Researchers put undergraduates in a functional MRI and showed them a series of irrelevant dates. The students were asked to press a “no” button if the date didn’t mean anything to them. Ganis also threw the subjects’ birthdays into the mix, telling them to lie and press “no” when that date displayed. Using a computer trained to recognize brain patterns, the researchers could accurately detect when the students were being deceptive.

But the students also were taught how to outwit the machine by “imperceptibly” moving a finger or a toe — basically to imagine moving them — when irrelevant dates appeared. That itself made the dates relevant, Ganis said, and the accuracy rate plummeted to 33 percent. “You are recalling something meaningful when you see the meaningless dates,” Ganis said. “The MRI can’t tell what’s going on.”

Ganis said that he has nothing against using MRIs for lie detection in the future but that more needs to be learned first about how the guilty could use similar tactics to trick the machine.

It’s unclear to me whether we’d ever get to the point where this technology can be considered sufficiently reliable to be used in Court. Polygraph technology has advanced greatly in recent decades, and it is commonly used in his security situations in the public and government sectors, but it’s still not considered appropriate for use in Court, and I’m not sure that it ever will or that it should. Putting the legal system in the hands of machines doesn’t strike me as a good idea.

Ultimately, the Judge in this Maryland case ruled that the brain scan could not be admitted into evidence, which strikes me as the right outcome. I doubt this will be the last time that an American court has to deal with this issue.

Graphic via The Washington Post

I would also note that being told to lie about something is different than lying to deceive. The brain patterns, I would imagine, could differ as well.

@mantis:

Indeed, which calls at least one of the studies mentioned in the article into question.

What you are saying is that traditional lie detectors correlate with the truth, but don’t nail it. You presume that X new technology will also correlate. That’s fine. In that case you can argue they should not be admissible because juries can’t in general handle statistical inference.

It’s a different thing if some device Y or Z gives us say 5 nines (99.999%) accuracy.

At that point you’ve beaten any reasonable expectation of trial by jury, and you should just junk the guilty phase and move on to sentencing.

(Shorter: technology yes, death penalties no, for the very reason that new tech or understanding can illuminate past errors of justice)

(I would guess that juries are actually less reliable than lie detectors, but that we don’t really want to know that.)

I fully agree that MRI machines are not ready for prime time as reliable lie detectors.

FWIW, there’s a fun science fiction novel called “The Truth Machine” postulating a near-future world in which lie detection is reliable. The story takes that as the premise, then uses it to demonstrate how radically it would change society (including business, law, personal relations, etc.)

I thought it was quite well-written and thought-provoking. One of the characters is a politician with national ambitions who sees the technology coming and plans his career in anticipation of its widespread use.

Here’s the Amazon link:

http://www.amazon.com/Truth-Machine-James-Halperin/dp/0345412885

The author James Halperin has also released a copy a free downloadable MS Word file:

http://coins.ha.com/c/content.zx?content=ttm

When your error bars run the length of the page, the accuracy of the signal is–surprise!–zilch.

God help us all if this technology falls into the wrong hands. By which I mean, wives.

I’m not convinced that any device can measure accurately. Just the other day I coincidentally stepped out of a building just as a police officer was investigating a burglar alarm. I wouldn’t say I panicked, but my physiological alarms were going off as he questioned me, and my mind raced to find ways to prove my innocence. Would this have set off this MRI lie detector? Heaven knows.

In the meantime, experienced liars can convince themselves they are telling the truth, and I’d be curious how well they are at beating such machines.

The last block quote suggests to me that the brainscan might not be effective for people with antisocial or narcissistice personality disorders, people who don’t feel/think there are any problems with lying or steeling and no sense of social constraints.

That would mean, the scan would not be effective on the people most likely to commit crimes, though that doesn’t mean they necessarily commited any given crime.

it won’t work on politicians who forgot how to tell the truth, ever…..lies just roll off their tongues and we keep electing them. maybe we’re just a bit too uptight to accept someone who isn’t close to perfect?

>It’s unclear to me whether we’d ever get to the point where this technology can be considered sufficiently reliable to be used in Court.

I agree with a lot of what you wrote in this article, but I think it’s pretty much inevitable that technology will one day be able to reliably determine what people are thinking–and, hence, to reliably know whether someone is lying or not. It could be decades or even centuries from now, but it will happen. As futuristic technologies go, it’s not in the same category as time travel or FTL or perpetual motion, where there are theoretical problems to its being possible.

This may sound scary, but there’s a possibility people will also concurrently invent ways of preventing intruders from probing our minds, sort of like the way anti-virus software and firewalls were created to protect computers from hackers. The movie Inception suggests one way in which that might happen.

A lot of you are going on the idea that the brain scan would use the same mechanism, tension, panic, etc.

If this, or some future tech, works on recall centers, which light when you describe things the subject has seen or experienced, then all those psychological factors go out the window.

And *I’m* saying that people can make up memories in their head that they think are real. See Hillary Clinton’s story about being fired upon in Bosnia. To her that may have actually seemed like a real memory even though she got the idea from a newspaper account or something.

So the question becomes: if the person thinks it was a real memory, is that being stored in the same recall center?

>if the person thinks it was a real memory, is that being stored in the same recall center?

From a legal perspective at least, having a false or inaccurate memory isn’t the same thing as lying–or else loads of eyewitnesses would be convicted of perjury.

Still, you raise a good question. My understanding is that people don’t access memories the way a computer does, where it’s just there and you retrieve it. Rather, recall is always an act of piecing together little bits from our mind, many of which aren’t part of the original experience. That’s why our memories of past events are almost always distorted in their details. What we call a memory is in fact largely a reconstruction, even when it happens to be reasonably accurate. So, unlike lying (which involves conscious intent), it may not be easy to distinguish a false memory from a real one even with a perfect mind-reading device.

@Kylopod:

My understanding is that memories use lossy compression, not only dropping detail, but merging with similar experiences. Interesting stuff. I could see how that method would be useful in dawn of humanity days. Merging deer hunts in the next valley is a useful way to think about deer hunts in the next valley.

As far as scans and law, as I say above I regard it as theoretical until it actually tests as accurate. And of course I oppose the death penalty because courts, technical and non, have been proven inaccurate in the past.

Ideally when something like hair analysis is proven BS we’d have the time, money, and compassion to re-investigate convictions based on hair analysis. It’s on our souls that we do not.

Review Found FBI Hair Analysis Flaws in 250 Cases, But DOJ Didn’t Inform Defendants and Public

@john personna: The interesting thing is, when I started reading about the science of memory, it seemed to confirm the conclusions I’d reached years ago from examining my own memories. One particular way I adduced the inaccuracy of my own memories was by watching movies I hadn’t seen for years–sometimes not since childhood. It was striking how often a scene or line of dialogue would stick in my mind then turn out to be, once I watched it again, significantly different than the original. It seemed that what I was doing was taking a mere impression I was left with (sometimes little more than a “feel” of the original scene) and combining it with other knowledge from my mind in order to flesh it out as a distinct memory. I’m not the only one: this is surely how you end up with all those famous misquotes (“Play it again, Sam,” “We don’t need no stinkin’ badges,” “Beam me up, Scotty,” and so on).

@Kylopod:

Heh, I read a whole book two days ago. I woke up yesterday and couldn’t remember what it was about. I had a bit of a panic that it might be me, and reviewed in my mind other books I’d read recently. I decided that it was just a really terrible book.

(Terrible science in it’s GMO, and a preposterous plot to get the First Lady crushing on a random ER doctor.)

I’ve also had the experience where vivid dreams (the realistic ones) have merged into memory to the point where I’d be hard pressed to state whether “X said [phrase]” or “I dreamed X said [phrase]”

@grumpy realist: I’ve had that experience too. The thing about dreams is that we experience a kind of amnesia upon awaking and have trouble remembering even a dream that was going on seconds earlier, unless we make a special effort to remember, like writing it down on a notepad next to the bed. (The reason, from what I’ve read, is that a lot of our dreaming is never transferred to long-term memory.) But sometimes in the middle of the day, something jolts us into suddenly remembering what we were dreaming the previous night–even though the memory is likely to be vague and lacking in context. That’s what leads to those weird experiences where we aren’t sure if we’re remembering something real or something we merely dreamt.