New York Gerrymander May Be Back

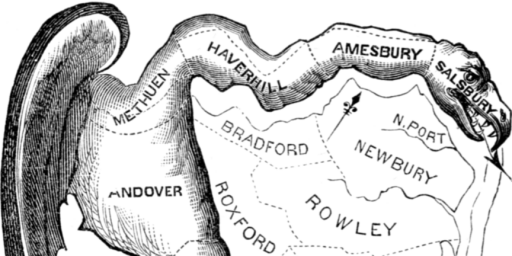

A never-ending saga of politicians choosing their voters.

Regular readers may remember that, a little over two years ago, the highly Democratic state legislature in New York rejected the Congressional maps drawn by the independent commission, substituting a wildly gerrymandered one instead. A few months later, though, the state’s highest court struck down that map, putting a more representative set of districts in play for the 2022 election.

In a plot twist, that court has overturned its previous ruling, potentially allowing another highly-skewed map the be used for the 2024 election. If that happens, it’s quite possible that it will decide the next Speaker of the House.

POLITICO (“New York’s high court just blew up the fight for control of the House“):

New York’s high court gave Democrats a big leg up in the dogfight for control of the House of Representatives.

The court on Tuesday vacated the ultra-competitive court-drawn congressional map used in the midterms, ordering the map to be redrawn. That process is ultimately controlled by Democrats, so the ruling opens the door for Empire State Democrats to gerrymander the districts, ousting several Republicans in one swoop.

[…]

We already know what such a Democratic gerrymander could look like — just look at the one they drew last time.

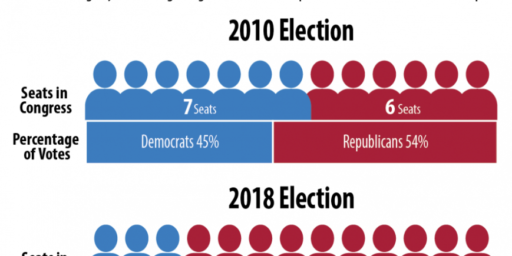

Democratic lawmakers drew a map last year that could have netted them as many as 22 of the state’s 26 seats. Instead, the court-drawn map had several competitive districts and resulted in a delegation of 15 Democrats and 11 Republicans.

Democrats this time could draw lines to edge out some Republican incumbents to try to guarantee some pickups — the all-GOP delegation on Long Island is probably sleeping less soundly tonight, as is Staten Island’s Nicole Malliotakis; the Hudson Valley’s Mike Lawler and Marc Molinaro; and central New York’s Brandon Williams.

Even a few surefire wins could help erase the hole Democrats nationally are facing after Republicans drew a potent gerrymander in North Carolina that will all but guarantee the GOP picks up three or four seats there.

Of course, the lines aren’t everything. Even with the court-drawn districts, President Joe Biden carried 20 of the state’s 26 districts by at least 4.5 points. But Democrats lost five of those 20 Biden districts.

It’s highly unusual to get a second bite at redistricting in a 10-year cycle. So what happened?

Simply, the judges changed.

All seven of the judges on the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court in the state, are Democratic appointees — both for the 2022 decision that led to the court-drawn lines and for Tuesday’s ruling reopening the process. Both decisions were decided 4-3.

But one seat changed. While six judges effectively ruled the same way both times, a seventh judge — in this case, a temporary replacement — was the deciding vote. She sided with the three dissenters in the 2022 case to make a new majority this year.

This is, well, not how it’s supposed to work.

Alas, it’s likely a good thing. As noted in my December 2021 post, “Unilateral Disarmament on Gerrymandering,”

My strong preference would be for bipartisan commissions to draw district lines that are based as much as possible on natural communities rather than naked partisan advantage or incumbent protection. But it makes no sense for one of two political parties to play the game that way while the other is doing everything the law will allow to gain an advantage.

And, as I detailed more fully in a commissioned piece for the New York Daily News in response to the 2022 court decision (“New York’s Gerrymandering Disarmament“) that’s exactly the situation.

The problem is that increasingly, the two parties are playing by different rules. In recent years, there has been a movement toward having electoral maps drawn by nonpartisan commissions, so that voters choose their representatives rather than the representatives choosing their voters. That’s a positive step. Alas, states run by Democrats, including California, New Jersey, Virginia and Washington, are much more likely to have adopted the practice, while Republican-controlled states are doubling down on gerrymandering. This is compounded by the tendency of Democratic-majority states to make voting easier while Republican-led states seek to make it harder, with a disparate impact on poor and minority would-be voters, who disproportionately favor Democrats.

Indeed, while New York Democrats gleefully rigged the game in their favor when given the chance, the opportunity only came because a deadlocked bipartisan commission charged with drawing unrigged maps failed to satisfy its constitutional responsibilities and the Legislature then ran with the ball. As we learned Wednesday, the 2014 amendment to the state’s Constitution that created this commission also prohibits the Legislature from partisan gerrymandering through the back door.

Meanwhile, Republican-controlled states like Texas, North Carolina and Florida are unchecked by these sorts of measures and are doing everything in their power to maximize their advantage. Even though these states are increasingly “purple,” you wouldn’t know it by their GOP-heavy congressional representation.

My strong preference is for all states to make voting easier and elections meaningful by having competitive districts. (Actually, I would rather eliminate districts entirely, but that’s not on the horizon.) It would maximize participation and representation. It would also be fairer to the fastest-growing voter type, the independent.

When only a Republican or only a Democrat can win a contest, the election is effectively decided in the party primary — and thus by the most ideological and motivated voters. That’s not only undemocratic but inevitably leads to bad governance, as politicians increasingly serve only their party base and move further to the extremes.

At the same time, though, it makes no sense for Democrats to hamstring themselves by rules their Republican opponents aren’t playing by. Doing so not only disadvantages them in individual contests but exacerbates an inherently skewed system.

Republicans already have a significant built-in advantage in the Senate, where each state gets two members regardless of population, and a modest one in the House. This carries over into presidential elections, through the mechanism of the Electoral College, giving us Republican winners in 2000 and 2016 in contests where Democrats won millions more votes. Republicans leveraging all the tools at their disposal to gain additional seats while Democrats opt for fairness stacks the deck even further.

This is made all the more urgent in light of the “Stop the Steal” movement and the Capitol riots. The Republican Party has increasingly decided that it can’t win fair elections and must therefore do everything in their power to rig the game. And, sadly, won’t accept losing even then.

That the New York Court of Appeals reversed their own ruling based on nothing more than a change in judges is, well, unorthodox. But, on balance, a better outcome given the circumstances.

Except, as you point out, the Republican US Supreme Court has made it repeatedly clear that is exactly how it should work. Why should the Dems unilaterally disarm?

Is it good for the people of NY? Is it fair? The Supremes have made it clear those things are immaterial.

A tangent, but I think this focus on partisan representation begs the question. The whole premise is misguided. In a fair system I don’t think the goals of redistricting should concern themselves in any way with the parties. For example, here in Baltimore and/or Maryland, a district that is narrow but surrounds the Inner Harbor/Chesapeake Bay makes a lot of sense. Politically, the Watermen might be as trumpy as the poultry farmers on the Eastern Shore, but more realistically those farmers are pouring oceans of chicken shit into the bay and affecting the crab harvest. Because the district is drawn to enhance political affiliation the Watermen’s concern about the health of the bay is diluted, because there are so many more agricultural voters in their district. On the other hand, the much more liberal voters of say, waterfront Canton, also want a clean bay. Shouldn’t districts be drawn by alignment of economic and geographic interests rather than carving up crazy patterns to make sure the number of Democratic or Republican delegates match party registration?

@MarkedMan: I am a fan of the use of natural boundaries (political boundaries or geographic entities like mountain ranges, rivers, etc.) and as few “turns” as possible – to the point I’d even legislate no more than 6-8 bends in a district boundary outside of a river course or the peaks of a mountain range.

Short of that I’d also support full randomization – for example: latitudinal lines across states that created a new district every time the line raised north enough to encapsulate enough people for a district.

This choosing of one’s voters bothers me even when “our side” wins.

I was going to post on this, but did have the time yesterday. Yet again, this is an illustration of the fundamental problem with single-seat districts: the lines are more important than the voters.

As such, this is why multi-seat districts using proportional representation is democratically superior. Full stop.

@Steven L. Taylor:

100% this–the lines allow you to get the voters you want.

Great overall article, James. And you are 100% right that so long as the current system stands there are incentives for both sides to do this (see also DeSantis’s recent veto of congressional lines in Florida, drawn by Republicans, for not being gerrymandered enough).

Which gets to:

Completely this, and this is also why there is so little incentive from either major political party to change the system as it stands.

@Steven L. Taylor:

But that doesn’t solve every problem of representation. And you can’t point to empirical data that the fix you push all the time actually results in better policy outcomes. So, I’m Jersey Rolling your full stop.

How dare you act like you have a panacea when your proposed reform has no shot of ever being enacted?

😉

@Kurtz: Ha!

Until there is a nation wide process agreed and put into law there is no point to not gerrymandering. Bye, Bye Elise Stefanik?

@Tony W:

The simple fact is there is no fair way to slice a pie. Johnny should get more ’cause he’s biggest. Tommy should get more ’cause he’s growing faster. Mary should get more because girls have been getting less. At some point you give up, slice the pie as equally as you can, hand the slices out randomly, and settle for procedural fairness.

And once there’s more than one issue, there are no natural communities. @MarkedMan:’s watermen and chickenshit farmers may be opposed on pollution, but maybe they both want the shore road widened. And the watermen and farmers with kids want the school levy, while the childless don’t. Do all thirty or so Black’s in Hamilton County NY have the same interests as Blacks in Bed-Sty?

Procedural fairness may not be entirely fair, but at some point it’s the best you can do. It’s the 21st century, software can easily be put together to start in a random corner of the state and generate a mesh of irregular polygons with equal population. I’d allow slight fudging to match existing roads, just to avoid splitting a house. We might, depending on the Supremes, lose majority minority districts under the VR, but in return the lege would lose the ability to split the Black vote into arbitrary majority white districts. You might still get screwed, but you’d be screwed by a transparent rule, not the gerrymandered redneck lege.

The lege and the courts would still amuse themselves by arguing about whether it’s equal population of people, or citizens, or registered voters, or any number of other things. But they’d be nibbling around the edges.

@gVOR10: Unfortunately, I think humans will never quite trust “done by a computer” as free from tampering. Maybe they shouldn’t.

The climate on this sort of thing is far, far different now than it was in 2004, say. Then, for instance, Republicans were all about adopting voting machines and Dems were suspicious of results in Ohio that were recorded on Diebold machines.

2020 and the roles are reversed. If a “computer generated” map turns out to be unfair to some group in some way, I think it’s extraordinarily likely that there will be suspicious of tampering, if not outright tampering.

Meanwhile, I certainly believe that one could construct such an algorithm that is procedurally fair.

As it turns out, though, I favor Steven’s style of proposal – Statewide proportional representation, for instance, or maybe something a bit finer grained for larger states. Because a human can look at the data and quickly ascertain that yes, this is the outcome determined by the voting that just happened.

@Scott:

This is both strategically true and also a clear degradation of representative democracy.

@Steven L. Taylor:

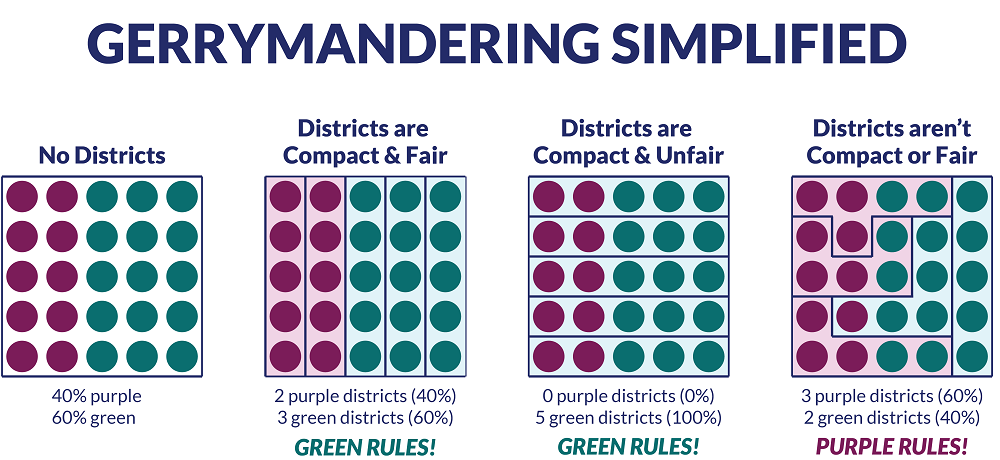

This is why I favor a gerrymander so egregiously awful that the Supreme Court has to step in. The third example in the graphic. It might be hard to do with New York’s shape, but I envision an Illinois starburst pattern with every district containing enough Chicago to outweigh then rural parts of the state.

A test case gerrymander.

Since many seem to be on soapboxes, I’ll get on mine and point out that increasing the size of the House would solve 80% of the problem and would, at the same time, have many other benefits, including addressing the problem of EC-PV mismatch – all without requiring a Constitutional amendment or the consent of state legislatures.

@Andy:

I am 100% in favor of expanding the House.

But I am dubious that such expansion solves anywhere near 80% of the problem.

@Steven L. Taylor: It might if the House was expanded to 6,000 members or so.

It is hopelessly simple to divide something between two people. I suppose suggesting it in the political domain is totally simple minded. But if attempted it might actually work.

One does the dividing; the other choses.

@Tony W:

Oh fwak no! 6000??? Oh dear [insert deity of your choice here] NO! Any of us who have ever attended a meeting of more than 20 stakeholders are cringing at the thought.

But wait, if we give all of the participants paintball guns, and allow this to deteriorate into a complete free for all, and run it is a pay-per-view, we can arguably take a huge chunk out of the deficit.

Hmmm… This may be crazy enough to work.

@Steven L. Taylor:

80% is a guess – obviously, this is a case where the details are dispositive in determining how big the effect would be. But the principle is pretty clear – smaller districts make it more difficult to draw contiguous geographical boundaries for the purpose of gerrymandering – with big districts, it’s a lot easier.

District sizes are also currently so large that it’s impossible to avoid even unintentional gerrymandering (See our map in Colorado, for example, which was done by a commission, but also makes little sense).