No, the Supreme Court isn’t about to Stop Congress from Delegating to the Executive

A law professor reads too much into a cryptic concurrence.

Jeannie Suk Gersen, a Harvard Law professor and contributor to The New Yorker, warns “The Supreme Court Is One Vote Away from Changing How the U.S. Is Governed.” While the incredible dysfunction of our government might have us longing for said vote, the change she forecasts is not of the beneficial variety.

The setup:

Gundy v. United States was about the “Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act,” known as sorna, which Congress enacted in 2006. The statute made it a crime, punishable by ten years in prison, for individuals convicted of a sex offense involving a minor to fail to register in each state where they live, work, or study. But Congress gave the Attorney General “the authority to specify the applicability” of these requirements to people convicted before sorna took effect. In 2007 and in 2011, Attorneys General Alberto Gonzales and Eric Holder said the requirements do apply to such people.

That group encompassed half a million people, including Gundy, who was convicted of sexual assault of a minor in 2005. After serving prison time for the crime, he went to live in a halfway house in New York in 2012. After he failed to register there, he was rearrested and convicted of the new federal crime. Gundy claimed that sorna violated the non-delegation doctrine, wherein it is unconstitutional for Congress to delegate its legislative power to the executive branch. He argued that letting the Attorney General determine whether the law applied to people like him left too much to be decided by an agency rather than by Congress.

Setting aside questions as to why the bill is known as sorna rather than the acronym SORNA, this doesn’t even strike me as a case that should make it to the Supreme Court. While I’d be amenable to the argument that retroactive application of what amounts to punishment is effectively an unconstitutional ex post facto law, the delegation of routine decisionmaking to the Attorney General would seem uncontroversial.

As Gersen explains,

For the better part of a century, the Court has permitted Congress to delegate broad policymaking authority to federal agencies. The Court has not struck down a statute under the non-delegation doctrine since 1935, when a conservative majority was hostile to progressive New Deal measures aimed at protecting workers and consumers. Since then, the increasing complexity of modern industrialized society has made it obvious that—even when Congress is not as dysfunctional as it is now—it’s not possible for Congress to legislate the technical details necessary to regulate the environment, health, safety, labor, education, energy, elections, discrimination, housing, and the economy.

As a result, executive agencies create regulations and implement binding policies. That has long been understood as both necessary for the country to function and consistent with the Constitution. The Court has applied a test: if a statute gives an agency discretion that is sufficiently constrained by an “intelligible principle,” then Congress is not unconstitutionally delegating legislative power. But many conservatives complain that that test has been applied in a lax way, so that any statute delegating any scope of authority appears to satisfy it. For example, the Court has repeatedly upheld statutes that give agencies only general guidance, such as to regulate in the “public interest,” or issue air quality standards “requisite to protect the public health.”

As noted in a recent post, even though I’m temperamentally conservative and skeptical of the vast expansion of Federal power and the rise of the Executive state, there’s simply no alternative to such delegation in a modern society. Congress simply doesn’t have the bandwidth or expertise to manage the details of lawmaking in a vast, complex, technologically-advanced world. They simply have to defer to experts in the Executive bureaucracy and then conduct oversight, effectively reversing the Constitutional order.

We have five Justices on the Supreme Court, however, who think we’ve gone too far.

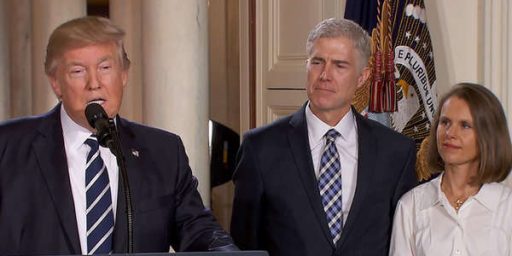

In Gundy, all four liberal Justices, in a plurality opinion by Justice Elena Kagan, hewed to the prevailing approach, finding that Congress provided enough guidance limiting the agency’s discretion to pass constitutional muster. Three conservative Justices, in a dissent by Justice Neil Gorsuch, said that the law impermissibly gave the Attorney General “free rein to write the rules,” and was unconstitutional. Justice Samuel Alito cast the deciding vote that enabled the liberals to prevail this time, but his three-paragraph concurrence made clear that the victory may be short-lived. He said that if the majority “were willing to reconsider the approach we have taken for the past 84 years, I would support that effort.” A conservative majority was lacking here because of the absence of Justice Kavanaugh. [Who had not been confirmed at the time the Court heard oral arguments in the case and therefore had to recuse himself. -jhj] Next time there’s a similar case before the Court, his vote will make for a different result.

We are now explicitly on notice that the Court will likely abandon its longstanding tolerance of Congress delegating broadly to agencies. What’s at stake is the potential upending of the constitutional foundations of the so-called “administrative state.” Today’s reality is that agencies, not Congress, make most federal laws. As Justice Kagan put it, if the delegation in Gundy were unconstitutional, “then most of Government is unconstitutional.”

Now, arguably, it is. But, despite my sympathy for a textual-historical approach to Constitutional interpretation, there has to be some concession to the practical realities of governing. Not to mention eighty years of precedent.

But Gersen seems to be over-interpreting Alito here.

What will happen then, when the conservative bloc prevails? The alarmist view is that the E.P.A. couldn’t have the power to decide how stringent pollution standards should be. The F.D.A. couldn’t have the authority to approve or deny applications to sell new medical drugs. The Department of Education couldn’t make rules for colleges and universities. The Department of the Interior couldn’t govern snow mobiles in national parks. The S.E.C. couldn’t regulate financial firms or securities. The F.C.C. couldn’t issue rules on net neutrality or Internet service providers. In sum, we would dwell in a world without the federal law that governs our lives.

I’m not reading Alito that broadly, however. Indeed, Alito CONCURRED in the judgment while Neil Gorsuch, Chief Justice Roberts, and Clarence Thomas dissented.

Still, his opinion, which I reproduce in its entirety below, is indeed cryptic:

The Constitution confers on Congress certain “legislative [p]owers,” Art. I, §1, and does not permit Congress to delegate them to another branch of the Government. See Whitman v. American Trucking Assns., Inc., 531 U. S. 457, 472 (2001). Nevertheless, since 1935, the Court has uniformly rejected nondelegation arguments and has upheld provisions that authorized agencies to adopt important rules pursuant to extraordinarily capacious standards. See ibid.

If a majority of this Court were willing to reconsider the approach we have taken for the past 84 years, I would support that effort. But because a majority is not willing to do that, it would be freakish to single out the provision at issue here for special treatment.

Because I cannot say that the statute lacks a discernable standard that is adequate under the approach this Court has taken for many years, I vote to affirm.

The Gorsuch dissent begins thusly:

The Constitution promises that only the people’s elected representatives may adopt new federal laws restricting liberty. Yet the statute before us scrambles that design. It purports to endow the nation’s chief prosecutor with the power to write his own criminal code governing the lives of

a half-million citizens. Yes, those affected are some of the least popular among us. But if a single executive branch official can write laws restricting the liberty of this group of persons, what does that mean for the next?

The argument that follows is long and winding. But, while it spends quite a bit of time—not unreasonably—warning of the rationale behind separation of powers and the Framers’ fears about handing off of legislative power to the executive, it also acknowledges not only that the Supreme Court started allowing delegation going back to Chief Justice Marshall’s tenure but that it was wise and reasonable to do so. He concludes:

In a future case with a full panel, I remain hopeful that the Court may yet recognize that, while Congress can enlist considerable assistance from the executive branch in filling up details and finding facts, it may never hand off to the nation’s chief prosecutor the power to write his own criminal code. That “is delegation running riot.” [emphasis mine–jhj]

Now, from my limited understanding of the facts of Gundy, I don’t believe Congress did that. Rather, it essentially ordered the Attorney General to apply registration to past convicts. The reason discretion was afforded was simply a recognition that, because it potentially applied to so many people, it was best to let those charged with the administration of justice figure out how and under what timetable to implement that mandate. The AG wasn’t tasked with writing a criminal code but rather with discretion as to how quickly to roll out the code Congress wrote.

Regardless, if we assume Kavanaugh will join forces with Alito and the three dissenters and thus create a five-vote majority, we seem to be in for some house-cleaning, not an overturning of the broad principle that Congress can delegate rule-making authority.

Indeed, Gorsuch flatly acknowledges longstanding principles:

First, we know that as long as Congress makes the policy decisions when regulating private conduct, it may authorize another branch to “fill up the details.” In Wayman v. Southard, this Court upheld a statute that instructed the federal courts to borrow state-court procedural rules but allowed them to make certain “alterations and additions.” Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Marshall distinguished between those “important subjects, which must be entirely regulated by the legislature itself,” and

“those of less interest, in which a general provision may be made, and power given to those who are to act . . . to fill up the details.”

Wayman v Southard was decided in 1825—almost 200 years ago now—and Gorsuch and company defer to it as gospel. After more discussion, we get to:

Second, once Congress prescribes the rule governing private conduct, it may make the application of that rule depend on executive fact-finding. Here, too, the power extended to the executive may prove highly consequential. During the Napoleonic Wars, for example, Britain and

France each tried to block the United States from trading with the other. Congress responded with a statute instructing that, if the President found that either Great Britain or France stopped interfering with American

trade, a trade embargo would be imposed against the other country. In Cargo of Brig Aurora v. United States, this Court explained that it could “see no sufficient reason, why the legislature should not exercise its discretion [to impose an embargo] either expressly or conditionally, as

their judgment should direct.”

Cargo of Brig Aurora is an even older case, dating to 1813. And, again, Gorsuch and company defer to it.

Third, Congress may assign the executive and judicial branches certain non-legislative responsibilities. While the Constitution vests all federal legislative power in Congress alone, Congress’s legislative authority sometimes overlaps with authority the Constitution separately

vests in another branch. So, for example, when a congressional statute confers wide discretion to the executive, no separation-of-powers problem may arise if “the discretion is to be exercised over matters already within the scope of executive power.”

Again, the dissenters are deferring to longstanding precedent.

So, what’s the fuss?

The argument is long and defies excerpting here but it boils down to the “intelligible principle” doctrine laid down in a 1925 case called J. W. Hampton, Jr., & Co. v. United States and its subsequent interpretation.

[W]hen Chief Justice Taft wrote of an “intelligible principle,” it

seems plain enough that he sought only to explain the operation of these traditional tests; he gave no hint of a wish to overrule or revise them

Basically, the dissenters think we should go back to those core principles and be wary of delegation that doesn’t fall within them. They believe the Court has become too lenient in applying the “intelligible principle” doctrine and thus allowed Congress to delegate actual policymaking judgment to the executive bureaucracy—a bridge too far.

The case law in question is sufficiently outside my scope of expertise that I don’t have a strong opinion as to whether that’s true or whether this revised thinking would too narrowly constrain Congress. But it’s not the radical undoing that Gersen suggests.

She closes,

The main idea of the non-delegation doctrine is that any law that is enforced against citizens must be approved by Congress. It’s not enough for Congress to say, “We should have a law on this subject and someone else will write and enforce it.” But this formulation is a rhetorical parlor trick. When building a house, one may have a strong idea of the kind of house one wants, but most of us have neither the knowledge nor the desire to make the thousands of key decisions about how to safely construct it. Those decisions are sensibly delegated to a contractor and an architect. A rule forbidding any delegation of that sort makes for very different, more rudimentary, building, and probably many fewer buildings built.

I’m not persuaded that this analogy is correct or, more importantly, that the application of the three principles Gorsuch points to wouldn’t permit Congress to subcontract in this fashion.

The more robust non-delegation doctrine that the conservative Justices desire would mean a change in the nature and scope of the federal government’s role in our lives. Conservatives favor making it difficult for the federal government to regulate, because, when it does, it risks impinging on our liberties. And, if the federal government does less, states may do more. The impact of this change will ultimately depend on which elected officials are in power, and that is really up to us, not the Supreme Court.

Again, I’m insufficiently expert to know how severe the impact would be. The three articulated and longstanding principles strike me as allowing rather robust delegation of the details so long as the broad policy is set by Congress.

Further, to the extent that delegation violates the provisions of the Constitution, it really is up to the Supreme Court, not to us and our elected officials, to draw the line.

James,

“Now, from my limited understanding of the facts of Gundy, I don’t believe Congress did that. Rather, it essentially ordered the Attorney General to apply registration to past convicts.

(snip)

Regardless, if we assume Kavanaugh will join forces with Alito and the three dissenters and thus create a five-vote majority, we seem to be in for some house-cleaning, not an overturning of the broad principle that Congress can delegate rule-making authority.”

While I am not an Administrative Law attorney, I think you are reading Gorsuch’s dissent wrongly. Indeed, the fact that Gorsuch dissented rather than concurred strongly suggests that he believes that the law in question did go over the line and should have been struck down. The precedent Gorsuch cited with approval held that the Executive branch can determine facts, but not make rules, while Alito was willing to follow this as a general rule, but not just in this single case.

The analysis of Gundy in SCOTUSblog said as much:

“Gorsuch closed by explaining that SORNA is unconstitutional under this stricter version of the nondelegation doctrine. He argued that SORNA does not involve filling up the details or “deciding the factual predicates to a rule set forth by statute”; nor does it involve an area of “overlapping” inherent Article II authority, such as the field of foreign affairs. Allowing SORNA’s delegation to stand, Gorsuch said, would “invite the tyranny of the majority that follows when lawmaking and law enforcement responsibilities are united in the same hands.”

Finally, Alito concurred only in the judgment, saying: “If a majority of this Court were willing to reconsider the approach we have taken for the past 84 years, I would support that effort.” Alito thus indicated that he would be receptive to future nondelegation challenges, but that he was not willing to rule in Gundy’s favor here: “[I]t would be freakish to single out the provision at issue here for special treatment.””

I also believe you are off-base in your conclusion:

“Further, to the extent that delegation violates the provisions of the Constitution, it really is up to the Supreme Court, not to us and our elected officials, to draw the line.”

Given that the gerrymandering cases were decided as they were because the Supreme Court refused to draw a line at all, this is not encouraging precedent for whether they will be willing to draw a line at all in delegation cases.

@Moosebreath:

Oh, we agree. But on rather narrow grounds. Kagan bent over backwards to construe the law as effectively ordering the AG to apply the law to past cases and Gorsuch said, no, it did no such thing and essentially left it to the AG to figure out for himself. I don’t have the time or expertise to figure out which interpretation to support—although I defer to the majority given Alito’s concurrence—but it’s a perfectly reasonable and narrow dispute.

These are opposite instances.

Delegation of Congressional authority is extraconstitutional but SCOTUS has understood for over 200 years that it’s a practical necessity and articulated rules for when/how it can be done. Conversely, states have near-plenary power to create legislative districts and SCOTUS has articulated narrow grounds over the years for constraining that power.

“No, the Supreme Court isn’t about to Stop Congress from Delegating to the Executive”

Too bad, because this is one of the fundamental problems with the current structure of American government, which has resulted in an Executive Branch that is far more powerful and bureaucratic than Article Two contemplates.

@Doug Mataconis:

I’m more of a Constitutional literalist than the next guy but we can’t govern a modern society entirely based on what some guys in a room in Philadelphia 230 years ago contemplated. They simply had no notions of telegraphs, railroads, airplanes, radio, television, the Internet, etc. It would be absurd to regulate those things exclusively at the state and local level and all of them are deeply integrated into interstate commerce, anyway. And it would be impossible for a bicameral legislature of 535 people, few of whom have any scientific background, to write laws regulating these things. The Supreme Court acknowledged as much even before the advent of these technologies, going back over two centuries when many of the Framers were still alive. Indeed, James Madison, the principal architect of the Constitution, was President when the first of these decisions came down.

@James Joyner:

That’s why the drafters of the Constitution made it possible to amend the Constitution. It’s inappropriate for either Congress or the President to essentially accomplish that via legislation that can pass by a single vote or by Executive Fiat.

In and of itself, you are perhaps right that delegation is necessary but there needs to be a better mechanism for Congressional review of agency action. Allowing unelected bureaucrats to have as much say over the operation of the government, and little means for Congress to review it is too far of a deviation from the plain language of the Constitution.

I come down on James‘ side of this, Doug. I have worked with plenty of growing companies where the founders are simply overwhelmed with the decision making that needs to happen that they can no longer do individually or at the Board level. Entities that don’t find a way to delegate these important decisions below the Board level (Congress) crash and burn because a Board cannot handle the big picture while trying to make it through the weeds of everyday business.

@Joe:

That’s an inapt analogy. The Constitution is not simply a “way of doing business” it is the Rule of Law.

@Doug Mataconis:

We don’t disagree. But, again, Congress started delegating the details of rulemaking to Executive agencies almost immediately and the Supreme Court held it Constitutional during the administration of the Father of the Constitution. It’s not a newfangled idea dreamed up by Earl Warren.

I’ve of late been reading a book about our legal system, The Nonsense Factory by Bruce Gannon. I’m in the chapter about how the whole regulatory system may, in theory, be unconstitutional. Not my line of territory, but apparently this line of thinking is hardly novel or fringe in RW legal scholarship. I am reminded that J. K. Galbraith observed that the power of large corporations can be “countervailed”, a word I believe he coined for the occasion, only by large powerful unions and powerful government. They’ve largely succeeded in getting rid of large powerful unions….

@James Joyner:

No it’s not a new idea. That doesn’t mean, though, that it’s permissible or should simply be allowed to continue because “this is how we’ve always done things.” As Gene Healy noted in The Cult of The Presidency, the ceding of power by Congress to the Executive has a long history, that doesn’t make it legally correct, though.

Long-standing precedent should be respected, but the idea that it should never be questioned is smply wrong.

@Doug Mataconis: Overturning existing precedent is risky and almost always has large unintended consequences, but I agree with you here. Congress has ceded far, far, too much power to the President. It has been a problem for many decades but the fuse was really lit by Gingrich and his crew, who decided that compromise for the sake of fulfilling fundamental responsibilities was just weakness. Certainly, almost all of the current Republicans and far too many of the Democrats are entirely too willing to let the President make their decisions for them and just tut-tut about it if they disagree.

@MarkedMan: Everybody likes power without responsibility, and congress has the power to make it so for themselves.

This is an aside, but I think it is relevant. Right now I’m working with two companies involved in medical products, but who fall into different grey areas. One involves organ transplants and the other involves IV fertilization products. Congress passed many many laws governing medical devices in general, but the rule writing was vastly more complicated and is so by necessity. And in these two cases, I’m seeing how the rules need to be incredibly well thought out to begin with but also amended over time to adjust for things unanticipated. When they were passing legislation designed to protect patients, neither Congress nor the writers of the rules spent all that much time thinking about something in between living people and dead people. Our whole legal system is based on the “time of death” which can only be traversed in one direction, but it only applies to whole human beings. How do we deal with organs not yet transplanted or ovum not yet implanted? Do devices used in their handling need to follow the same rules and regulations as devices used for human beings? The actual answer is “no, with some exceptions”. Those exceptions are done for the sake of the safety of the eventual recipients, but were done as rules, not as acts of Congress. There are probably hundreds or thousands of such adjustments needed in the medical rules, each requiring deep thought and study. The US Congress is not in any way shape or form the right way to deal with this type of thing (“Sorry, the regulation that would allow you to get that kidney is being held up because Senator Foghorn has attached an anti-flag burning amendment to it”)

Don’t get me wrong, neither of these areas are some kind of libertarian sh*t-show, although IV is closer to that. But the point is that the regulations that come about to keep that from happening would never make it to the top of a Congressional Pile. 535 people simply couldn’t handle these issues along with the tens of thousands of similar issues that pop up every year. (Month?)

@Doug Mataconis:

Sure. And while these precedents are tangential enough to my previous study that I don’t have a firm opinion, I’m sympathetic to Gorsuch’s reasoning. That is, the extremely longstanding rationales for delegation are set in stone but maybe more recent decisions allowing delegation if there’s just a plausible rationale have gone overboard. I think some tightening up almost certainly makes sense. But rebooting to 1787 would be bad policy and upend the basis for the Common Law.

@MarkedMan: I’ve only had a little bit of Admin Law and that was within the context of a political science-public administration program a long, long time ago. I don’t see much choice but to delegate the complicated details to experts in the bureaucracy. But, given the financial incentives and the nature of bureaucratic inertia, I don’t know that it’s possible for regulations to keep up with the facts on the ground in fast-moving industries. And that presumes that things are all working as they should in theory and that there’s no regulatory capture.

I remember that when during passage of the 2,000 page healthcare act, many critics lamented the length and breadth of the legislation. Ironically, these same critics support the delegation doctrine (which is what we are talking about here). Essentially, this is libertarian advocacy framed like a constitutional question. No legislation can ever anticipate all future postulations which does require an interpretative executive. The danger here is that a judge may use the doctrine to support a preconceived (political) notion. Essentially this doctrine is a minefield and we have yet to see how many laws it blows up. On a larger issue, this shows that any retrograde argument gets a full hearing at the Supreme Court which does not speak well about the institution or how the law is being practiced in this country. We need judges to stop stupid arguments not encourage them.

@James Joyner:

Amen to that brother. Fortunately for me now that I’ve become directly involved in regulatory matters, the Medical Industry is far, far from “fast moving”.

@Raoul:

That was a stupid argument that played to people’s ignorance.

Can my comment be released from moderation? Thanks in advance.

@Raoul:

Since my comment was not released, I will make it again:

“I remember that when during passage of the 2,000 page healthcare act, many critics lamented the length and breadth of the legislation. Ironically, these same critics support the delegation doctrine (which is what we are talking about here).”

The same applies to the Internal Revenue Code, and how many of the same people who oppose delegating rule-making authority to the Executive branch also complain about the length of the Code.

I’ve never fully understood this argument. Why not simply move the rule-making bureaucracy from the Executive agencies over to Congress and then have the final step of approving a rule developed by that bureaucracy be a vote in Congress? A vast apparatus of expert civil servants is certainly necessary to effectively develop the rules that govern much of our day to lives in the modern world, but I don’t see why we can’t simply change the org chart so the box labeled “rule-making bureaucracy” reports up to Congress instead of the President. Constitutional problem solved, no?

@R.Dave:

The entire bureaucracy is a rule-making bureaucracy. Essentially, you’re arguing for having the Executive branch fall under Congress.

@James Joyner: Well, that’s not entirely true. Most agencies also have a very large enforcement/implementation function as well, and that would all stay with the Executive. But sure, I grant that it would obviously be a huge transfer of personnel from one branch to the other, but I don’t see that as an insurmountable obstacle. In the private sector, whenever one company acquires another, basically everything below the senior management level stays the same at first and it’s just the upstream reporting chain and the ultimate decision-maker(s) at the top that change. That’s more or less what I’m envisioning here.

At any rate, notwithstanding my use of the word “simply”, I’m not under any illusion about the difficulty involved in the transition, and it would certainly have to be done over a period of years rather than all at once. That said, I think the benefits – greater Constitutional fidelity, increased accountability to (and of) the elected legislature, and diminution of Executive power – would be worth the trouble. More to the point, though, I just don’t understand why the issue always seems to be characterized as a choice between virtually unconstrained delegation to the Executive and the collapse of modern governance, and I rarely if ever see anyone suggest the option of transferring the rule-making bureaucracy back to Congress.

@R.Dave:

It’s an interesting idea that I haven’t given much thought to. This is one of those “we’ve always done it that way” situations. Literally from the beginning, Congress started creating Executive agencies to carry out its specified powers. I suppose the Patent Office or Census Bureau could be part of Congress but it would be weird. And I’m not sure how one separates “rule-making” from “execution” in that they go hand-in-glove. It’s not impossible, I suppose, but would require constant coordination across branches.

@James Joyner: Well one could create a new or several new bureaus to monitor interactions between the agencies or perhaps we can rearrange the deck chairs of the Titanic: is a solution in search of a nonexisting problem – the Executive governs (it really is as simple as it sounds constitutionally) and this has never been a problem until the incindieries (what I call this branch of libertarianism) concocted an issue- recall the real objective here is not how to run the government but to emasculate the government. Now as a practical matter, I don’t see something like this working unless you hire hundreds of thousands of people and then that would be just the beginning. And once that happens I can imagine a brand new doctrine from the same people called the “anti-delegation doctrine” – where they charge the legislative with usurping executive power- the whole thing is a charade.

@Raoul:

This simply isn’t true in the case of the US system of government. The Framers quite deliberately split the governing power between a legislative and executive branch, with the judicial branch acting as something of a referee. The system simply wasn’t designed for the massive administrative state that simply couldn’t have been foreseen in 1787 and we’ve been trying to figure out how to live within the spirit of the Constitution but the practicalities of reality ever since.

@James Joyner: There is nothing in the Constitution on delegation: one branch legislates, another executes and the other adjudicates. The formulation is indeed rather simple. It should go without saying that the more complicated the law, the more complicated its application. Current discussion on how this is supposed to work is starting to resemble a master’s class discussion in philosophy. The one consistency I have found in conservative circles is that one attaches a doctrine or viewpoint to their preordained political notions until they no longer fit. Like being a strict constructionist or applying the equal protection clause (a recent book revealed that Scalia thought that the opinion in Bush v. Gore was a joke but that did not stop him voting for it). Roberts essentially declaring sections of the 14th amendment unconstitutional should finally lay to rest the thought that conservative jurisprudence has any real constitutional foundation. So yes, spare me this “trying to figure it out” the constitutional framework- it seems pretty evident that the judges vote is predetermined by their current political views and one searches for “doctrines” (which are mostly made up from thin cloth) when one is needed for some kind of legal justification.

@Raoul:

Sure. But it isn’t simple in practice. Even in a much simpler system—a much smaller country geographically that was pre-industrial and where most governance was local—Congress delegated power to the Executive and the courts ruled it permissible.

Once cases reach the Supreme Court, it’s practically inevitable. And it was true of even very early landmarks like Marbury v. Madison or McCullouch v Maryland. Judges bring different legal philosophies to the table, none of which are inherently wrong. And they naturally balance competing interests differently.

Someone referenced “THE MYTH OF THE RULE OF LAW” by John Hasnas the other day. It explains this last bit rather well.