Republicans At A Foreign Policy Crossroads

For the first time since the end of World War II, the GOP is wrestling with two diametrically opposed visions of foreign affairs.

A new poll conducted for The Hill shows that the American public is becoming increasingly skeptical of the nation’s vast overseas military commitments:

An overwhelming number of voters believe the United States is involved in too many foreign conflicts and should pull back its troops, according to a new poll conducted for The Hill.

Seventy-two percent of those polled said the United States is fighting in too many places, with only 16 percent saying the current level of engagement represented an appropriate level. Twelve percent said they weren’t sure.

Voters also do not think having U.S. soldiers fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq has made the country safer, according to the poll.

Thirty-seven percent said the continued presence of U.S. troops in Afghanistan makes no impact on national security, while another 17 percent said it makes the United States less safe. By contrast, 36 percent said the United States is safer because forces are in Afghanistan.

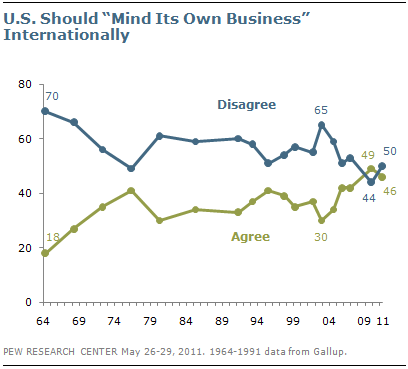

These results are similar to the results of a more comprehensive Pew Research poll released last week that showed the American public agreeing with the statement that the United States should “mind its own business” in international affairs:

Poll results like these, as well as others that show overwhelming public opposition to U.S. involvement in Libya, and strong support for the idea of withdrawing from Afghanistan sooner rather than later, are one of the reasons that we’re seeing Republicans becoming more willing to question foreign military adventurism than they were int he past. Yes, the fact the President is a Democrat is certainly part of it for them, but that’s not different than Democrats who reacted to public opposition to the Iraq War by being against the Iraq War (but only a little bit, of course, you didn’t see Pelosi or Reid try to cut off funding after capturing Congress in 2006). Taking advantage of shifts in public opinion is what’s politics about, after all.

Ross Douthat takes note of this phenomenon today in a column pointing out that, for perhaps the first time since the end of World War II, the GOP faces a choice between two competing visions of foreign policy:

while this division shows up in the current presidential field, it’s distilled to its essence in two high-profile Republicans who aren’t running (not in 2012, at least): Senator Marco Rubio of Florida and Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky.

As The American Spectator’s Jim Antle pointed out last month, Rubio and Paul have followed similar paths to prominence. Both were discouraged from running for the Senate by party leaders. Both rode Tea Party support to unexpected primary victories. In Washington, both have defined themselves as stringent government-cutters.

But on foreign policy, the similarities disappear. Rubio is the great neoconservative hope, the champion of a foreign policy that boldly goes abroad in search of monsters to destroy. In the Senate, he’s constantly pressed for a more hawkish line against the Mideast’s bad actors. His maiden Senate speech was a paean to national greatness, whose peroration invoked John F. Kennedy and insisted that America remain the “watchman on the wall of world freedom.”

Paul, on the other hand, has smoothed the crankish edges off his famous father’s antiwar conservatism, reframing it in the language of constitutionalism, the national interest and the budget deficit. (As Matt Continetti noted in The Weekly Standard, “Whereas Ron Paul criticizes U.S. interventionism in tropes familiar to the left — anti-imperial blowback, manipulation by neocons, moral equivalence — Rand Paul merely says America doesn’t have the money.”)

In a recent address at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, Paul presented himself as the real foreign-policy “moderate” — neither an isolationist nor a Wilsonian idealist, but someone who believes we should be “somewhere some of the time” without trying to be “everything to everyone.”

But even this measured critique of interventionism makes a striking contrast with Marco Rubio’s worldview. Where Rubio talks sweepingly about America’s mission in the world, Paul expresses skepticism about nation-building and democracy promotion. Where Rubio invokes World War II and the cold war, Paul invokes the founding fathers’ fears about executive power and overseas entanglements. Where Rubio borrows Ronald Reagan’s expansive rhetoric, Paul praises Reagan’s caution in committing American troops to foreign wars.

They do share some common ground. Both emphasize peace through strength. Both are skeptical of international institutions. And Paul has been at pains to express support for operations like the one that killed Osama bin Laden.

But the right’s two rising stars would ultimately take the Republican Party in very different directions. This has been apparent in the debate over the Libyan quasi war. Both senators have criticized President Obama’s handling of the intervention. But Rubio has argued that we should be striking harder against Qaddafi, while Paul has dismissed the war as both unwise and unconstitutional.

Of course it is Paul’s views that seem to be gaining in public support these days, which is likely one of the many reasons that people like John McCain are going on tirades against “isolationism” in the Republican party. As David Boaz notes, however, the spectre of actual isolationism is far less prevalent than McCain and his cohorts would like people to believe:

There aren’t isolationists in the contemporary American debate. The Britannica defines isolationism as “National policy of avoiding political or economic entanglements with other countries.” Who’s calling for isolationism, with its historical connotation of protectionism and cultural isolation? Surely not businessman Mitt Romney, who ran the Olympics, and whom McCain singled out. Surely not former deputy trade representative and ambassador to Singapore and China Jon Huntsman, whom Pletka indicts. And certainly not the free-trading, immigration-friendly Cato Institute, a center of noninterventionist thinking.

Although Boaz doesn’t mention him, it’s also clear that neither Senator Paul nor other foreign adventurism skeptics in Congress such Tom McClintock, Justin Amash, and Walter Jones, does not fit the classic definition of an “isolationist.” Being opposed to intervening in the internal affairs of other nations that are not a threat to our national interests is not the same as isolating oneself from the world, nor is recognizing the fact that not every problem in the world is capable of being solved by U.S. intervention, whether diplomatic or otherwise. Labeling this new genre of non-interventionism as isolationist is merely an ad hominem attack designed to cut off debate. Call someone an isolationist, after all, and you’ve basically equated them with the America First crowd who, up until the attack on Pearl Harbor, didn’t believe that the United States should worry itself one bit about the rising expansionism and militarism of Japan and Germany. That kind of attitude is just as foolish as the attitude that says that we need to make the world, or the Middle East, safe for “democracy,” and both are likely to lead to disaster in the end because neither looks at the world realistically.

When it comes to foreign policy, the GOP is at a crossroads. Laid out before them are the competing visions Rubio and Paul. One would send us out into the world fighting endless wars that we cannot afford to pay for, fighting for allies that we can barely trust, and causes that we don’t understand. The other merely asks us to look at the world, and our interests realistically, and realize, perhaps, that not every problem can be solved by massive application of American military force. The public already seems to know where it wants to go, and the foreign policy elites inside the GOP seem scared:

Maybe GOP pols are beginning to catch on that, for quite some time now, ordinary Americans have overwhelmingly rejected the globocop role forced on them by liberal and conservative elites. Indeed, there’s a huge disconnect between the foreign policies Americans favor and those the Beltway Consensus delivers. Nearly three-quarters of the American public wants to get out of Afghanistan yesterday; meanwhile, 57 percent of National Journal’s “National Security Insiders” think we need to waste more blood and treasure on armed “community organizing.”

It’s almost like there’s a “culture war” going on, but not one of the usual God, Guns, and Gays variety. On one side, you’ve got the sound, mind-your-business instincts of the American people; on the other, there’s a gaggle of intellectual elites, determined to extend the reach and power of the American state.

How the battle turns out will have consequences not only for the GOP, but for America as a whole.

I believe the Pew (and/or Gallup?) have long used similar polling as a stated “isolationist” metric. I don’t think it’s intended to be an ad hom attack.

While I think public opinion is most galvanized on issues of war, the poll question also raises concerns with “fair trade” and a variety of international projects.

I don’t currently own a machine that would take me to an alternative universe, but I strongly suspect that in a universe in which Americans are worried about a double-dip recession or where future jobs are coming from, they are still not interested in making global warming concessions even if the U.S. was not engaged in three wars.

I disagree.

I think a large majority of Americans just aren’t that interested in what the U.S. military is up to in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, the Philippines, Mexico, etc., etc., etc.

Afghanistan was a reasonable response to a brutal attack. We should have beefed up security afterward and made punishing Al Qaeda and its allies our only priority in the War on Terror. Sadly Washington in the guise of the Bush Administration grossly overreached and tried to do too much outside the scope of what was necessary. Thankfully Americans are now rejecting the idea of the US as an international nanny state and beginning to favor a more balanced foreign policy between the extremes of blind isolationism and rabid interventionism.

Going in to eliminate Al Qeda’s camps was a reasonable response. Trying to reform a notoriously ungovernable country into a modern democracy was not. We should have focussed on locating at eliminating the forces responsible and then left, with a warning to the general populace not to make us need to come back.

Foreign Policy has released its list of failed states (what a topic for a blog post!).

America has had a hand in most of the top ten.

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/06/17/2011_failed_states_index_interactive_map_and_rankings

Maybe it’s time we realized we’re no longer a force for good and call it a day…