Stuxnet and America’s Cyber Credibility

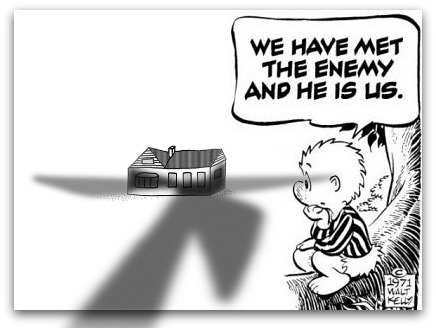

The United States may have slowed down Iran's nuclear program without firing a shot--not counting the one at our own foot.

Revelations that the United States is responsible for the Stuxnet virus and has been waging cyber war on Iran since the Bush administration have been greeted with interest but not much controversy, at least domestically. After all, Iran is a bad actor and stopping its development of nuclear weapons through non-violent means seems like a no-brainer.

My Atlantic Council colleague Jason Healy, who directs our Cyber Statecraft Initiative, believes otherwise. In a post titled “Stuxnets are Not in the US National Interest: An Arsonist Calling for Better Fire Codes,” he argues that this effort has likely destroyed American credibility in an increasingly important arena.

Few in the world will ever believe the peaceful motives of the United States in cyberspace again, giving us even less leverage to ensure this new cyber dimension develops in a way encompassing America’s wider economic and security interests.

Cyberspace is “the backbone that underpins a prosperous economy and a strong military and an open and efficient government,” according to President Obama. Because of this importance, not much more than a year ago, the president committed the United States to “work internationally to promote an open, interoperable, secure, and reliable” cyberspace “built on norms of responsible behavior.” He wrote that, “While offline challenges and aggression have made their way to the digital world, we will confront them consistent with the principles we hold dear: free speech and association, privacy, and the free flow of information. The digital world is no longer a lawless frontier … It is a place where the norms of responsible, just and peaceful conduct among states and peoples have begun to take hold. ”

Stuxnet was not an act of peaceful conduct.

Saying one thing in public while doing the opposite covertly in the shadows happens of course all of the time between governments. China is, for example, behind large-scale global cyber espionage at the same time as it asserts that such acts are illegal and forbidden.

But the United States is the one that very publicly got caught and the timing could hardly be worse. The future of the Internet is being decided and post-Stuxnet, more nations are likely to side with the Russians and Chinese.

[…]

The most important reasons why Stuxnets are not in US interests revolve around the basic argument that “those with glass industrial control systems should not throw stones.” The United States has incredibly vulnerable cyber systems, including in critical infrastructures like the electrical generation and transmission systems. Not only has the United States legitimized attacks against these systems, they are now likely open to direct reprisal from Iran.

DHS officials have testified to Congress they are “concerned that attackers could use the increasingly public information about [Stuxnet] to develop variants targeted at broader installations of programmable equipment in control systems.” General Alexander of US Cyber Command similarly told lawmakers that “Attacks [such as Stuxnet] that can destroy equipment are on the horizon, and we have to be prepared for them.” The government has been clear about the proper response to Stuxnet and other threats with Alexander writing to Congress that “Recent events have shown that a purely voluntary and market driven system is not sufficient. Some minimum security requirements will be necessary” using regulation to secure critical infrastructure.

The message to the US private sector therefore seems to be that they need to be regulated because they are not protecting themselves sufficiently against a weapon designed and launched by their own government. The arsonist wants to legislate better fire codes.

Jay isn’t a pointed headed academic–he’s an Air Force Academy grad, a plankholder (founding member) of the Joint Task Force-Computer Network Defense, the world’s first joint cyber warfighting unit, and served as Director for Cyber Infrastructure Protection at the White House from 2003 to 2005.

I think he’s right here, even though my knee-jerk instinct is the same as everyone else’s. I argued for years against the notion that the Bush Administration was going to take us into a shooting war in Iran, simply on the basis that very few experts believed there were good military options. Given the universal notion that an Iranian nuke was “unacceptable” combined with a lack of ability to do much to prevent its becoming a reality, it was likely impossible to turn down a plan to do it through a cyber back door. (Ditto the escalation of the drone war in Pakistan, Yemen, and elsewhere.)

In terms of the bilateral relationship with Iran, there’s very little downside. A year ago, Jay wrote piece called “Bringing a Gun to a Knife Fight: Striking Back in Cyber Conflict,” pointing to the Obama administration’s declaration that it reserved the right to respond to a cyber attack with a kinetic one. That is, a country that launched a virus that crippled our critical infrastructure shouldn’t feel comfortable that our response would be limited to one in kind–we might bomb the hell out of them. While the reverse is of course true as well, the fact of the matter is that Iran has few good options for a military reprisal here.

But foreign policy is more than a series of bilaterals. Our actions in Iraq a decade ago damaged our relationships with our European allies and otherwise negatively impacted our ability to influence international policy. If Jay’s right, this action against Iran–while seemingly more successful on the ground than our adventure in Iraq–may be much more damaging to our soft power.

Sounds like they are using the Operation Fast and Furious justification, the US government sends weapons to foreign countries then uses the existence of such weapons to justify tighter control and suppression of freedoms.

Nice, who needs enemies when we have a government like this?

Although granted the acts by US actors seem to have at least had some success in Stuxnet.

The cyberwar Pandora’s Box is opened. Good luck getting anyone to ever believe our peaceful cyber intentions from now on. To all parties, we are the ultimate hypocrites who act in the “Might is right” mode. When (and I’m not saying ‘if,’ because it’ll happen) someone attacks our civilian cyber infrastructure and cripples it, there will not be great sympathy from many in the world. We better prepare for that eventuality.

It is my understanding that our electrical generation and transmission systems are not really vulnerable. I also think the rest of the world got the message when we invaded Iraq. I doubt that they will be even more likely to see us as an aggressor nation after this. (On a side note, we have had the opportunity to interact with a number of Asian college students this year. They were generally from the top of their class and have relatively affluent families. Most of them had sympathies with Iran and very negative views about Israel.)

Steve

That ship sailed some time ago.

Which is nice, but hardheaded “warfighters” aren’t the only valid opinion-holders. I’m sure you didn’t mean to imply they are, but I’m really sensitive lately to our tendency to validate opinions by pointing out that some people in or from the military hold them. Even Digby did this in her piece defending Chris Hayes last week.

If only “pointy-headed academics,” peace activists, civil-libertarians and tech bloggers opposed Stuxnet-style cyberwarfare and every single active and retired member of the officer corps thought it was awesome, it would not, in itself, mean it was awesome. The officer corps and its alumni are not trumps.

@Jim Henley: I fully agree–and have written a whole litany of posts railing against the chickenhawk meme and the notion that military service entitles people to a privileged position in the debate. At the same time, I recognize that there’s a strong bias in some quarters against academics and think tankers, who are viewed by some as reflexive pacifists without a clue about the realities of the world. I disagree with that presumption, but I recognize that it exists. So, I was just heading that particular ad hominem rebuttal off at the pass.

@James Joyner: Oh, I get you. I freely admit I reflexively jumped on my hobby horse there. Did the same with Digby on Twitter earlier in the week. I do think that fetishizing (as opposed to respecting) the military as an institution is a terrible habit for a democratic republic and that as a society we’re way into the danger zone, though. Someone like you, who has a lived experience of the military as a human institution and no vested interest in making it an object of idolatry, isn’t personally vulnerable or culpable. But the official discourse is pretty far gone already.

At some point in the future – and I sincerely hope I am long dead when it arrives – we are going to be on the receiving end of the kind of war-by-other-means or pre-emptive-strike operations we regularly undertake on the blissful assumption that we’re on the moral high ground and the other side is The Bad Guy.

And then we’ll be able to accurately judge just how much we like war.

Not sure about that analogy. If the US didn’t develop cyberweapons, someone else would have. I think in this case it’s more like the casino hiring the card sharp. It’s just good business.

Not sure I like the idea of government worm going loose on the world though. Sounds like the premise of a really boring movie.

I can’t wait for the RIAA/MPAA sponsored Stuxnet variant.

Because that’s coming to a computer near all of you very soon.

Warfare ain’t never purty, and it don’t matter if it’s grunts and guns, unmanned drones, ship-borne guns and missiles, or in the Tron universe.

I wholeheartedly disagree with Mr Healy. An example:

Anyone who believed this was incredibly naïve. That’s an attitude that’s just not realistic. We’re going to fight cyber war. It has always been just a matter of when, and if we would be proactive or reactive.

No, it wasn’t. Thank God.

But it was tremendously better than any alternative out there, including the impotent, ineffective “diplomatic sanctions” regime the world has embarked upon.

While I would never say that the US’s role behind Stuxnet won’t have any impact on international negotiations over the Internet, it’s also naïve to believe that Russia and China wouldn’t have much the same influence they’ve got now, post-Stuxnet. And there’s absolutely no doubt that whether ITU “controls” the Internet (an impossibility anyway), repressive regimes will impose all those undesirable features on the Internet within their respective countries.

Everyone around the globe has to regard the Internet the same way we (should) regard email. It’s analogous to posting on the bulletin board at your local supermarket: anybody who’s paying attention will know what you said. Even moreso, they’ll also know what brand of pen you used to write it, where you were just before you went to the supermarket, the color of your socks and just about anything else they want to know, unless you put in a lot of work to hide all that information.

If people ever regard the Internet as “a safe place,” they’ll be setting themselves up for catastrophe. We need to regard it with fear, and take appropriate precautions. Just as Iran should have done, to protect themselves from the likes of Stuxnet. Sure, it’s a cyber-arms race now, but who could possibly believe it wasn’t one already?

Then again, I could have just riffed on Healy’s status as a former Air Force officer, but that would have been too easy.

[/ end of interservice and officer-enlisted rivalry post]

Why would anyone expect this not to be standard procedure?

And, I would expect that if we launched a war against Iran, we would have computer viruses disrupting their communications, power, water, and as much of their infrastructure as possible.

Same as if we launched a war against Russia or China, actually.

It’s a tool for war, and a relatively welcome one. Far too much military research has been pointed in the direction of how can we make a war more massively devastating. Things like this, drones, and smart bombs can make military action less devastating, and keep war at a low simmer rather than a fierce boil. Lower civilian casualties is a good thing.

Of course, if we ever think we can disable some country’s ICBMs, that makes it easier for us to launch ours without the fear of retaliation.

@Boyd: The problem is twofold. First, the Internet is mostly a peaceful domain for information and commerce. And the United States is not only its inventor but its main producer and consumer of content. We stand to benefit most from international regulations along lines that we propose. This has hampered our ability to achieve that. Second, we’re not actually at war with Iran.

@Gustopher:

And if another country thinks we’d be able to disable their ICBM’s, that arguably makes it more likely that they would launch out of fear that we would leave them defenseless and vulnerable.

That’s the danger that some saw in the entire idea of SDI/Star Wars and while I think it was likely overblown in that case mostly because the technology in the 80s to create a perfect missile defense didn’t exist, and doesn’t seem to exist today, I would argue that it’s far more likely in the case of CyberWar. If we can get a virus into the computer network of an Iranian nuclear plant that is physically cut off from the Internet, what can’t we do?

I’m not saying this isn’t a field we shouldn’t pursue. Indeed, at this point we pretty much have to because we know others will be doing it as well. But, I’m wondering if we may come to think that this was a genie that should have been left in the bottle.

@PJ: It already has actually. Most of their stuff targeted file sharers directly but there are some things they did that indirectly targeted potential file sharers..