Supreme Court Punts Another Political Gerrymandering Case

The Supreme Court term began with hopes that the Justices would shake up the redistricting process with rulings against partisan gerrymandering. It has ended with three whimpers.

Less than a week after it declined to rule on the merits in a pair of political gerrymandering cases, the Supreme Court on Monday declined to hear a similar case arising out of North Carolina:

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court passed up an opportunity on Monday to take another look at whether the Constitution bars extreme partisan gerrymandering, returning a case from North Carolina to a trial court there for a further examination of whether the challengers had suffered the sort of direct injury that would give them standing to sue.

The move followed two decisions last week that sidestepped the main issues in partisan gerrymandering cases from Wisconsin and Maryland.

The new case was an appeal from a decision in January by a three-judge panel of a Federal District Court in North Carolina. The ruling found that Republican legislators there had violated the Constitution by drawing the districts to hurt the electoral chances of Democratic candidates.

The decision was the first from a federal court to strike down a congressional map as a partisan gerrymander.

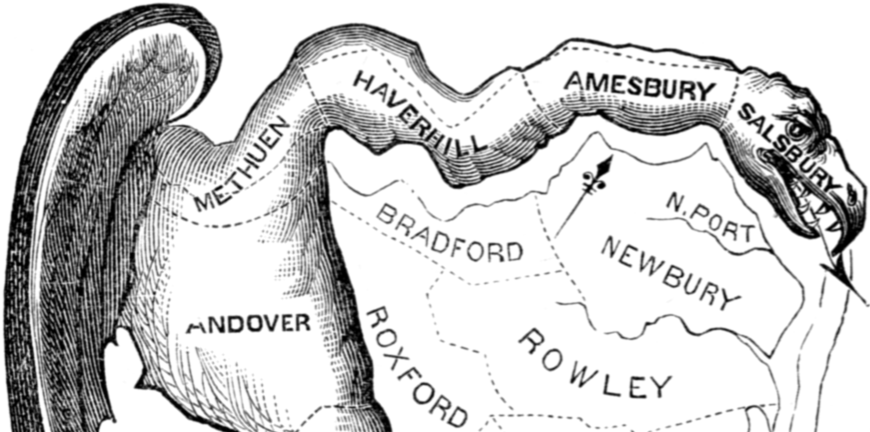

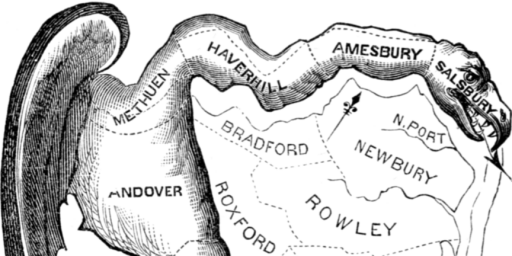

The judges noted that the legislator responsible for drawing the map had not disguised his intentions. “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats,” said the legislator, Representative David Lewis, a Republican. “So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country.”

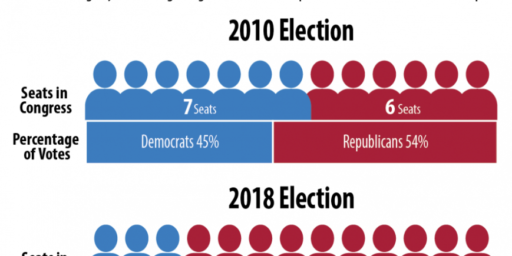

The plan worked. In 2016, the court said, Republican congressional candidates won 53 percent of the statewide vote. But they won in 10 of the 13 congressional districts, or 77 percent of them.

Amy Howe comments for SCOTUSBlog:

The justices also sent Rucho v. Common Cause, a partisan-gerrymandering case from North Carolina, back to the lower court for it to reconsider the case in light of Gill v. Whitford, last week’s ruling rejecting the argument by voters alleging partisan gerrymandering in Wisconsin that they could contest the entire state map. The challengers in the North Carolina case, who won in the lower court, had urged the justices not to return the case to the lower court, telling the Supreme Court that they can show a legal right to sue because (among other things) they have individual plaintiffs living in each of the state’s 13 congressional districts. But the state’s Republican legislators had argued – we now know, successfully – that the case “merits the same fate as” the Wisconsin case.

In some sense, the Court’s decision to decline review and remand this case back to the lower court is similar to the manner in which they dealt with the case of a Washington state florist who had been found in violation of the state’s anti-discrimination laws when she refused to provide services for a same-sex wedding. In that case, the Court ordered the tribunals below to reconsider the case in light of its rather limited holding in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case. In this case, the Court is essentially doing the same thing in that it is charging the lower court with reviewing its holding in the underlying case in light of the Supreme Court’s ruling in the two cases last week, particularly the ruling in the Wisconsin case that held that the Plaintiffs lacked standing to challenge the entirety of the state redistricting map rather than a single district or districts in which they might live. The North Carolina Court will now be required to determine whether the Plaintiffs have the same standing issues that the Court found in the Wisconsin case and, if they do, would likely be obligated to walk back the previous ruling and rule against the challengers solely on the issue of standing.

All of this makes for a fairly anti-climactic outcome from the Supreme Court on an issue where it was hoped that we might actually get some guidance on how far was too far when it comes to legislative district lines that drawn for what clearly seem to be clearly political purposes. In each of these cases, the intent to benefit one political party over the other seems to be rather obvious. In the Gil v. Whitford, the Wisconsin case that the Court vacated for lack of Article III standing, that intent seemed apparent based on the fact that the state’s Congressional delegation was far more Republican than the state’s electorate as a whole, something that was supported by a series of mathematical formulas that found a wide disparity between statewide voting patterns and the makeup of the delegation. In Benisek et al v. Lamone et al, the case arising out of Maryland, the partisan intent behind redrawing the map in a way that pushed a traditionally Republican district into deeply Democratic territory in the Maryland suburbs close to Washington, D.C. seemed rather clear and indeed accomplished its goal of pushing longtime Congressman Roscoe Bartlett out of office. In the North Carolina case, though, we not only have the map itself but also comments from Republican members of the state legislature that explicitly set forth their intent in drawing the map the way that they did. Instead of providing guidance of any kind on that issue, though, the Supreme Court disposed of all three cases on procedural grounds in a way that makes one wonder if anyone will be able to raise a successful challenge to political gerrymandering in the future.

The SCOTUS just spelled the end of public sector unions…and the middle class…ruling that public sector workers who are represented by unions cannot be required to pay any union dues.

The damage this is going to do the economy is immeasurable.

Every teacher, cop, and fireman that used to make a decent wage…now won’t.

The end of the middle class is nigh.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl: It’s not like unions are thriving now:

It’s true that the rate is higher in the public sector.

Still, that means 65.6 percent of us aren’t represented by unions.

But let’s save that discussion for the post on that ruling. Doug appears to be drafting one now.

@Doug: I know remanding to the lower courts for reconsideration is a longstanding SCOTUS practice but it’s always struck me as an odd one. If you’re going to grant cert and take the time to hear oral arguments and write opinions, why not just issue a damn ruling?

@James Joyner:

Sometimes a case is remanded because the matter the Court was ruling on was based off a preliminary ruling in the case rather than a ruling on the merits, thus meaning that the case needs to proceed further on the merits and that can only happen on the trial Court level. In the travel ban case, for example, the Court was only dealing with a Preliminary Injunction rather than a final ruling on the merits. Blocking the injunction merely means that the ban can go forward while the court below takes further action to proceed on the merits based on the Supreme Court’s ruling. That’s not something the Court can do.

In other cases, it’s simply a housekeeping move since its generally considered to be outside the jursidiction of an appellate court to do anything other than rule on the questions before it. Any further action, such as a dismissal in light of the Court’s ruling, would have to come from the District Court in a Federal case or from whatever lower court has jurisdiction in a case arising out of the courts of a particular state.