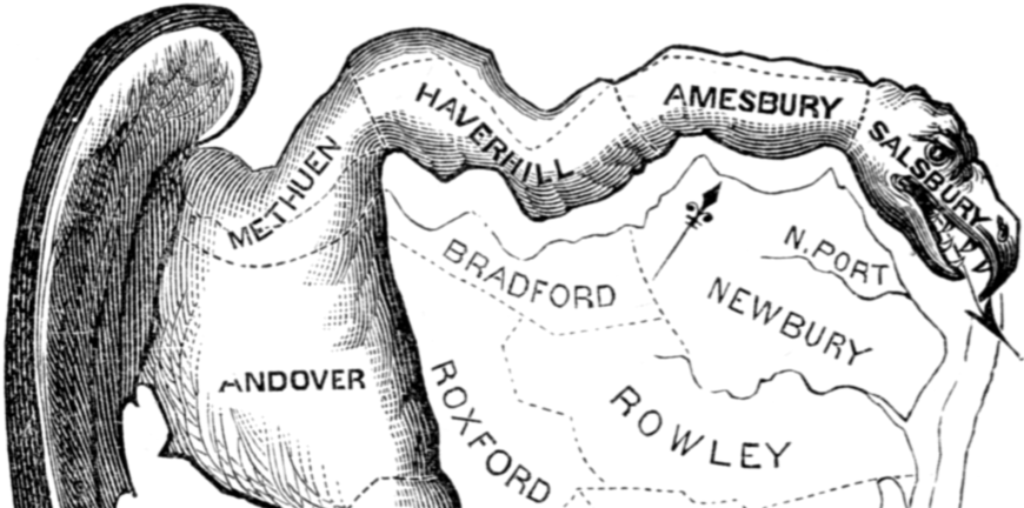

Federal Judges Rule Ohio Congressional Districts Are Unconstitutional

A panel of three Federal Judges has found Ohio's Congressional District map to be unconstitutional, but a case currently pending before the Supreme Court could mute the impact of this decision.

A panel of three Federal Court judges in Ohio has found that the Buckeye State’s Congressional district map is unconstitutional because it gives Republicans too much of a partisan advantage, but the impact of the case may be diminished depending on the outcome of a case currently pending before the Supreme Court:

A federal court on Friday tossed out Ohio’s congressional map, ruling that Republican state lawmakers had carved up the state to give themselves an illegal partisan advantage and to dilute Democrats’ votes in a way that predetermined the outcome of elections.

The ruling, by a three-judge panel from the Federal District Court in Cincinnati, ordered new maps to be drawn by June 14 to be used for the 2020 election, when Democrats will fight to preserve their House majority. The ruling will go directly to the United States Supreme Court for review.

(…)

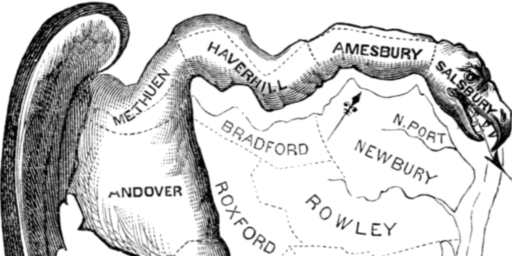

Ohio’s maps, in effect since 2012, have solidified a congressional delegation that has remained unchanged in four elections, yielding 12 Republicans and four Democrats — or 75 percent for one party in a swing state that has trended Republican in recent years, but where presidential and statewide elections are often close.

In their sharply worded, unanimous opinion, the judges wrote that Republicans in Ohio, supervised by party mapmaking experts in Washington, operated with “invidious partisan intent” to pack Democrats into as few districts as possible, and to carve up Democratic-leaning cities and counties to favor Republicans.

Hamilton County and the city of Cincinnati, for example, were split in a “strange, squiggly, curving shape” to divide Democrats, the judges wrote. Meanwhile in Franklin County, which includes Columbus, Democrats were concentrated in a “sinkhole” that allowed mapmakers to “secure healthy Republican majorities” in two suburban districts.

“In this case,” the judges wrote, “the bottom line is that the dominant party in state government manipulated district lines in an attempt to control electoral outcomes and thus direct the political ideology of the state’s congressional delegation.”

The suit was filed and argued by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Representative Marcy Kaptur, a Democrat from Toledo, testified at the two-week trial that her district, which winds along the shore of Lake Erie all the way to Cleveland and is derisively nicknamed “The Snake on the Lake,” was the epitome of extreme gerrymandering. The trial revealed that Republican mapmakers operated out of a hotel room they called “the bunker,” and in one email, a national consultant referred to downtown Columbus, which is heavily Democratic, as “dog meat” territory.

Republicans’ representatives argued at trial that the maps were drawn to protect incumbents of both parties and that there was nothing illegal in doing so.The three judges, two of whom were appointed by Democratic presidents and one by a Republican president, disagreed.

“We conclude that the 2012 map dilutes the votes of Democratic voters by packing and cracking them into districts that are so skewed toward one party that the electoral outcome is predetermined,” the judges wrote in their 301-page decision.

While the Federal courts have a long history of considering cases involving gerrymandering on racial lines, the trend of the courts dealing with cases where districts have been drawn for the purpose of benefiting one party or another is relatively new. The trend began, for the most part, with cases out of Wisconsin and Maryland in which the districts drawn by the respective legislatures were challenged for different reasons.

In the Wisconsin case, it was the Republican Party that benefited overwhelmingly from the manner in which the map was drawn statewide.

Among the primary pieces of evidence that the Plaintiffs relied upon in support of their arguments was a somewhat complex mathematical algorithm that purports to find that Wisconsin’s Congressional districts are far more heavily biased in favor of the GOP than should be expected if the district lines were drawn with geographic contiguity and other concerns in mind.

In the Maryland case, it was the Democratic Party that benefited from a redrawing of the boundaries of the state’s Sixth Congressional District that shifted it significantly eastward into the suburbs around the District of Columbia, thus making it more Democratic and pushing Roscoe Bartlett, a longtime Republican incumbent from a generally Democratic state, out of office in 2012 and diluting the political impact of the heavily Republican areas of western Maryland that borders Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

When the Supreme Court accepted these cases for oral argument, there was speculation that they could lead to landmark rulings that would place serious limits on the ability of state’s to draw districts that benefited one political party over the other. When oral argument was heard in both cases, though, it was clear that the Justices were divided on the issue and unsure about the implications of issuing the kind of landmark rulings that the Plaintiffs in both cases were hoping for. Many speculated at the time that the fate of the two cases would depend on where former Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy stood on the cases. In the end, though, the Court ended up issuing unanimous rulings that punted the cases on procedural issues rather than getting to the substantive legal issues raised by them. In one case, Gil v. Whitford, the Court held that the Plaintiffs in the case had failed to demonstrate that they had legal standing to challenge the entire redistricting map in Wisconsin. In the second case, Benisek et al v. Lamone et al.,the Justices ruled that the Plaintiffs in the case had failed to demonstrate the grounds necessary to receive a Preliminary Injunction from the District Court to prevent elections in Maryland’s Sixth Congressional District based on the 2011 map. Both cases were remanded back to the relevant District Court for further proceedings. The Benisek case that the Justices agreed to accept on Friday is essentially a second bite at the appellate apple for the Plaintiffs.

While those cases were pending in the Supreme Court, though, there was a far more interesting and potentially groundbreaking case pending in North Carolina. In that case, a three-Judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina issued a ruling last January that struck down that state’s map, ruling that the map was unconstitutional because it had been unfairly drawn for the primary purpose of achieving a partisan advantage for Republicans.

In the opinion, the Court cited evidence of partisan intent in the comments of the legislators at the time it was imposed as well as the extent to which the map clearly benefited Republicans over Democrats to the point where the GOP now holds ten out of the state’s thirteen Congressional seats notwithstanding the fact that this isn’t even close to being representative of the population of the state as a whole. Specifically, the Court found that the legislature had been “motivated by invidious partisan intent” in drawing the map and that, as a result, violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection. In reaching this decision, the judges applied the same three-part test that had been applied by the District Court in Whitford, finding that the map (1) was drawn with the specific discriminatory intent of benefiting one political party and harming the other, (2) resulted in a demonstrably discriminatory effect in that it created a map that created a decided partisan advantage for the party that drew the map and, (3) that there was no legitimate justification for this outcome other than the conclusion that it was drawn with the intent of discriminating against one party and in favor of the other. That ruling, though, was on a preliminary injunction, and it wasn’t until August of last year that the Court ruled that North Carolina’s map was unconstitutional. It’s that ruling that the Justices have agreed to review.

It was this case that the Supreme Court agreed to hear in January, and oral argument was heard in the case in late March. As James Joyner noted at the time, the Justices appeared to divide into their liberal and conservative camps. with the conservatives apparently willing to let state legislatures continue to draw district lines for partisan purposes. The opinion in that case is expected by the end of the current term of the Court in June and will likely impact any future action in this case and other pending around the country.

More recently, another panel of Federal Judges in Michigan found that state’s Congressional maps to be unconstitutional. The decision in that case was something of a hybrid of the Wisconsin and North Carolina cases in that the Court found that a statistical analysis similar to the one conducted in Wisconsin found that the map gave Republicans a far greater advantage over Democrats than ought to be expected if the map is drawn for purely innocent reasons. Additionally, the Court found evidence that Michigan legislators drew the map with the specific intent of helping Republicans and hindering Democrats.

As Nicholas Stephanopoulos explains at Election Law Blog, the Ohio case is somewhat unique from the other three. The first distinction is the fact that, unlike the previous cases, the ruling in this case was unanimous among the three Judges and the strongly worded opinion, which runs to more than 300 pages, reflects the fact that all three Judges agreed that the evidence of deliberate partisan gerrymandering was and is overwhelming:

Second, the Ohio decision adopted the same partisan vote dilution standard as the earlier Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin rulings. Under this test, “Plaintiffs must prove (1) a discriminatory partisan intent in the drawing of each challenged district and (2) a discriminatory partisan effect on those allegedly gerrymandered districts’ voters. Then, (3) the State has an opportunity to justify each district on other, legitimate legislative grounds.” The Ohio decision was also particularly clear about the role of plan-wide measures of partisan asymmetry in this analysis. These metrics “reveal if, and by how much, the map benefits one party over another by facilitating the more efficient translation of that party’s votes into seats.” “Multiple partisan-bias metrics should be used, and consistency across metrics and across data sets is key in evaluating this type of evidence.” Districts should thus be invalidated only if they belong to a map whose “partisan-bias metrics all point in the same direction” and reveal that “the redistricting plan is an historical outlier in its partisan effects.”

Third, the Ohio decision was the first to confront a serious argument that the Voting Rights Act justified the map’s bias. According to the defendants, the VRA required them to draw a black-majority district in northeastern Ohio (District 11, stretching from Cleveland to Akron) and thus to pack Democrats in that district. But as the court pointed out, there was no evidence of “effective white bloc-voting” in northeastern Ohio, meaning that no VRA claim in that area could succeed. In addition, the defendants made District 11 much more heavily black than it needed to be to elect a black-preferred candidate. “A 45% BVAP would be sufficient to elect the black-preferred candidate by a comfortable margin.”

And fourth, the Ohio decision was the first to analyze the plaintiffs’ associational claim using Anderson-Burdick balancing—a framework that Dan Tokaji has long advocated. As Dan has explained, Anderson-Burdick properly focuses courts’ attention on how severe the plaintiffs’ associational burdens are. Only heavier burdens trigger heightened scrutiny; lighter burdens, of the kind imposed by many district maps, result in something closer to rational basis review. Anderson-Burdick also properly instructs courts to balance the plaintiffs’ associational burdens against the government’s justifications for them. It thus avoids condemning all (or even most) maps designed by a single party: a scenario that several justices have warned against. Time will tell if the Ohio court’s use of Anderson-Burdick proves as durable as the partisan vote dilution standard it adopted.

All in all, this is a good decision for those seeking to place limits on the authority of state legislatures to mold districts for partisan advantage. As Paul Waldman and Greg Sargent note, though, it is likely to be short-lived

The Supreme Court has never ruled partisan gerrrymandering unconstitutional. But in March the high court heard a case involving the gerrymanders in North Carolina (made by Republicans) and Maryland (made by Democrats). We’re still awaiting the court’s decision in that case.

But it doesn’t look promising. Judging by oral arguments in that case — and in another recent gerrymandering punt by the court – the conservative justices seem to believe there’s no workable standard to distinguish between a map gerrymandered so unfairly that it violates the Constitution, and one that doesn’t, even if they wanted to.

In the Ohio ruling, judges ruled that an overly partisan gerrymander is created when the outcome of elections is “predetermined” to a degree that unconstitutionally violates voters’ right to political association by making it harder for some voters to advance their political aims.

But this decision will ultimately be appealed to the Supreme Court — and with the other cases also being heard, there’s little reason to think this will be upheld.

As noted above, the oral argument in the North Carolina case that was held in March makes it seem as though the conservative wing of the Court does not believe that there is or can be an objective measure of when a particular district map is too partisan or benefits one party or the other to a greater degree than it should. If this is the direction that the ruling in the North Carolina case goes then it will be next to impossible for the rulings in either the Michigan or Ohio cases to be upheld and the states will be generally free to draw district lines however they see fit, meaning that whichever party is in power at the time of redistricting will obviously draw a map that benefits one party over another.

Some states have started to respond to this by changing their laws to provide that district lines will be drawn by a non-partisan commission of some kind with the hope that the result will be a “fairer” map. Last year, for example, Ohio voters approved such a scheme in a referendum. The problem with that approach is the fact that the Supreme Court issued a ruling in 2015 that, while it upheld such as scheme in Arizona it also placed limits on just how much authority could be taken away from the state legislature. As a result, the possibility of continued partisan gerrymandering even when these supposedly non-partisan procedures are used remains.

In other words, there is reason for the opponents of partisan gerrymandering to celebrate this decision, but that celebration is likely to be short-lived.

Here’s the opinion:

Ohio Philip A Randolph Inst… by on Scribd

I fully understand that there is, ultimately, no perfect way to draw single seat districts (which is why I favor a different system altogether), but if we cannot at least come to some agreement that blatant, calculated, computer-driven partisan gerrymandering has to stop, then we really cannot claim to have a House of Representatives in any real sense of the term.

SCOTUS seems likely to continue us down that road despite what the lower courts keep saying.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Isn’t this simply another example of party trumping separation of powers?

@Steven L. Taylor: Strikes that at some point, John Roberts will have to decide if he wants to maintain any sense of respect for SCOTUS or wants to permanently cast it as inherently partisan in the public’s opinion.

Yes, it has always been partisan but the bulk of the Country didn’t see it that way. The onservatives on the Court have been spending the goodwill as partisan currency since Bush v. Gore but the account is not pretty much empty. Putting their thumbs on the scale in these gerrymandering cases – when *all* recent lower courts are going in the other direction – or overturning Roe will about do it.