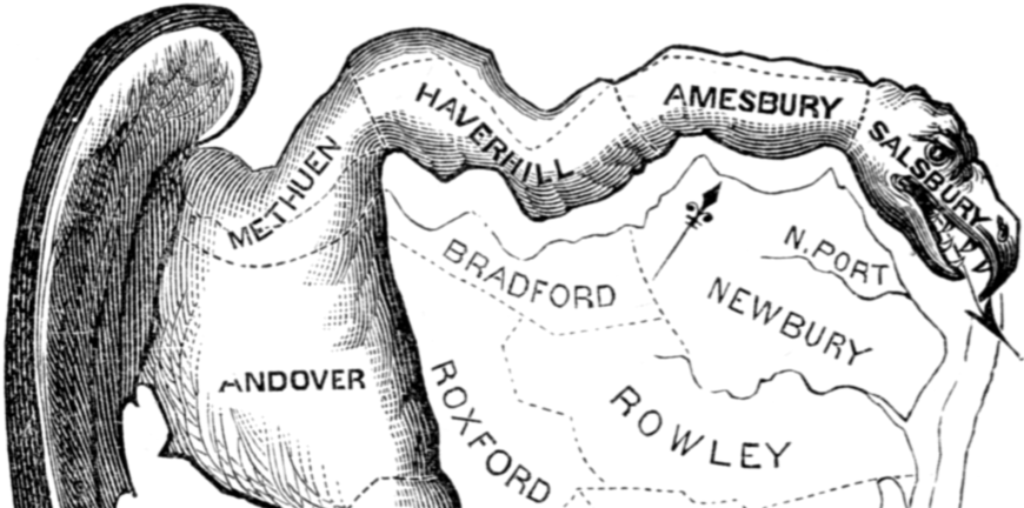

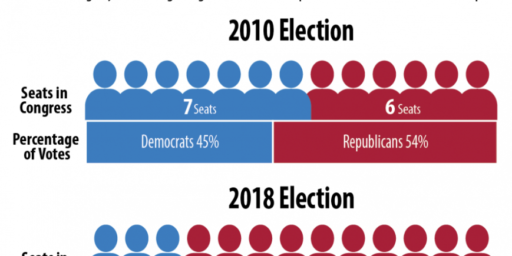

Supreme Court Takes Up Two New Partisan Gerrymandering Cases

The Supreme Court is taking up the issue of partisan gerrymandering. This time, though, they're likely to reach the merits of the cases rather than punting like they did last year.

Late last week, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a pair of new cases dealing with partisan gerrymandering:

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court agreed on Friday to take another look at whether the Constitution bars extreme partisan gerrymandering. The move followed two decisions in June in which the justices sidestepped the question in cases from Wisconsin and Maryland.

Those earlier cases had raised the possibility that the court might decide, for the first time, that some election maps were so warped by politics that they crossed a constitutional line. Challengers had pinned their hopes on Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who had expressed ambivalence on the subject, but he and his colleagues appeared unable to identify a workable constitutional test.

Justice Kennedy’s replacement by Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh makes a ruling limiting partisan gerrymandering less likely, election law experts said. Indeed, the court could rule that the Constitution imposes no limits on the practice.

The court’s decision to add two new cases on the question to its docket did not signal any particular enthusiasm for the project. While the court has almost complete discretion in deciding whether to hear most kinds of cases, Congress has made an exception for some disputes concerning elections. In those cases, Supreme Court review is all but mandatory.

The justices will hear arguments in March and are expected to rule by the end of June.

The first case the court took up, Lamone v. Benisek, No. 18-726, is a sequel to the one from Maryland that it declined to decide in June.

The case was brought by Republican voters who said Democratic state lawmakers had in 2011 redrawn a district to retaliate against citizens who supported its longtime incumbent, Representative Roscoe G. Bartlett, a Republican. That retaliation, the plaintiffs said, violated the First Amendment by diluting their voting power.

Mr. Bartlett had won his 2010 race by a margin of 28 percentage points. In 2012, he lost to Representative John Delaney, a Democrat, by a 21-point margin.

In 2017, a divided three-judge panel of the United States District Court in Maryland denied the challengers’ request for a preliminary injunction. In dissent, Judge Paul V. Niemeyer, who ordinarily sits on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, in Richmond, Va., wrote that partisan gerrymandering was a cancer on democracy.

“The widespread nature of gerrymandering in modern politics is matched by the almost universal absence of those who will defend its negative effect on our democracy,” Judge Niemeyer wrote. “Indeed, both Democrats and Republicans have decried it when wielded by their opponents but nonetheless continue to gerrymander in their own self-interest when given the opportunity.”

“The problem is cancerous,” he wrote, “undermining the fundamental tenets of our form of democracy.”

The challengers appealed to the Supreme Court, which unanimously ruled against them in June. In a short, unsigned opinion, the court said the challengers had waited too long to seek an injunction blocking the district.

In November, the three-judge panel took a fresh look at the case and ruled that the challenged district was unconstitutional. It barred state officials from conducting further congressional elections using the 2011 maps and ordered them to draw new ones.

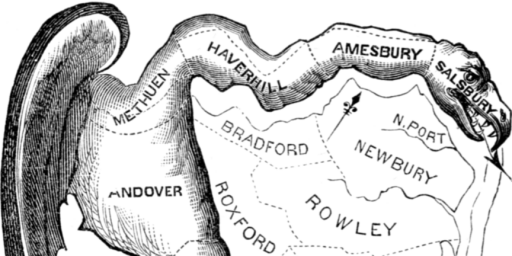

The second case, Rucho v. Common Cause, No. 18-422, is an appeal from a decision in August by a three-judge panel of a Federal District Court in North Carolina. The ruling found that Republican legislators there had violated the Constitution by drawing the districts to hurt the electoral chances of Democratic candidates. The court stayed its decision, and the 2018 election was conducted under the old map.

The case had reached the Supreme Court once before. In June, the justices ordered the lower court to reconsider an earlier ruling in light of the Wisconsin decision. That earlier decision, issued in January, was the first from a federal court to strike down a congressional map as a partisan gerrymander.

After reconsidering the case, the three-judge panel basically reaffirmed its earlier ruling. The judges noted that the legislator responsible for drawing the map had not disguised his intentions. “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats,” said the legislator, Representative David Lewis, a Republican. “So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country.”

The plan worked. In 2016, the court said, Republican congressional candidates won 53 percent of the statewide vote. But they won in 10 of the 13 congressional districts, or 77 percent of them. Depending on the outcome of one seat in the midterm elections in November, the numbers in the 2018 election will be identical or quite similar.

As noted, the decision to accept these two cases comes just about seven months after the court unanimously let the existing Congressional maps in Wisconsin and Maryland stand notwithstanding the allegations that both had been drawn in a manner to protect the interests of one political party or the other. In the Wisconsin case, it was the Republican Party that benefited overwhelmingly from the manner in which the map was drawn statewide. In the Maryland case, it was the Democratic Party that benefited from a redrawing of the boundaries of the state’s Sixth Congressional District that shifted it significantly eastward into the suburbs around the District of Columbia, thus making it more Democratic and pushing Roscoe Bartlett, a longtime Republican incumbent from a generally Democratic state, out of office in 2012 and diluting the political impact of the heavily Republican areas of western Maryland that borders Pennsylvania and West Virginia. When the Court accepted these cases for oral argument, there was speculation that they could lead to landmark rulings that would place serious limits on the ability of state’s to draw districts that benefited one political party over the other.

When oral argument was heard in both cases, though, it was clear that the Justices were divided on the issue and unsure about the implications of issuing the kind of landmark rulings that the Plaintiffs in both cases were hoping for. Many speculated at the time that the fate of the two cases would depend on where former Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy stood on the cases. In the end, though, the Court ended up issuing unanimous rulings that punted the cases on procedural issues rather than getting to the substantive legal issues raised by them. In one case, Gil v. Whitford, the Court held that the Plaintiffs in the case had failed to demonstrate that they had legal standing to challenge the entire redistricting map in Wisconsin. In the second case, Benisek et al v. Lamone et al.,the Justices ruled that the Plaintiffs in the case had failed to demonstrate the grounds necessary to receive a Preliminary Injunction from the District Court to prevent elections in Maryland’s Sixth Congressional District based on the 2011 map. Both cases were remanded back to the relevant District Court for further proceedings. The Benisek case that the Justices agreed to accept on Friday is essentially a second bite at the appellate apple for the Plaintiffs.

The more interesting case, though, is the one arising out of North Carolina. In that case, a three-Judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina issued a ruling last January that struck down that map, ruling that the map was unconstitutional because it had been unfairly drawn for the primary purpose of achieving a partisan advantage for Republicans. In the opinion, the Court cited evidence of partisan intent in the comments of the legislators at the time it was imposed as well as the extent to which the map clearly benefited Republicans over Democrats to the point where the GOP now holds ten out of the state’s thirteen Congressional seats notwithstanding the fact that this isn’t even close to being representative of the population of the state as a whole. Specifically, the Court found that the legislature had been”motivated by invidious partisan intent” in drawing the map and that, as a result, violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection. In reaching this decision, the judges applied the same three-part test that had been applied by the District Court in Whitford, finding that the map (1) was drawn with the specific discriminatory intent of benefiting one political party and harming the other, (2) resulted in a demonstrably discriminatory effect in that it created a map that created a decided partisan advantage for the party that drew the map and, (3) that there was no legitimate justification for this outcome other than the conclusion that it was drawn with the intent of discriminating against one party and in favor of the other. That ruling, though, was on a preliminary injunction, and it wasn’t until August of last year that the Court ruled that North Carolina’s map was unconstitutional. It’s that ruling that the Justices have agreed to review.

Given the speed with which the Justices have agreed to hear cases on this issue, it seems unlikely that they’ll punt on the manner that they did last June. That being said, though, the outcome of the cases is entirely unclear although it seems as though the road ahead will be difficult for those challenging the respective maps. As I noted, in the past Justice Kennedy was seen as a key in these gerrymandering cases given some things he has written and said on the matter in previous cases. Those remarks left many people siding with the parties hoping for a ruling against partisan gerrymandering hopeful that Kennedy would be the deciding factor in a decision that would sharply limit the ability of political parties to draw district lines to their advantage. Now, though, Justice Kennedy has been replaced by Justice Kavanaugh who, along with Justice Gorsuch, doesn’t really have a discernible record of ruling on these types of cases so we’ll have to wait until oral argument in March to even get a hint of where they might come down in these cases. Until then, you can review the filings in the two cases — Lamone v. Benisek and Rucho v. Common Cause — at their respective SCOTUSBlog information pages.

This is a Republican court. There is almost no doubt they will rule in the way they feel is most advantageous to their party. I imagine something along the lines of “It is up to the States” in the case that favors the Republicans and “But there is a special exception” in the case that favors the Dems. The latter is essentially the logic they used to push aside the State and put George W. Bush into the White House.

Of course, partisan gerrymandering is something that both parties engage in, as the Maryland case, and the recent events in New Jersey have demonstrated.

@Doug Mataconis:

Agree 100%. Which is why it will be (sadly) entertaining and see how the Republican Justices thread the needle and go against Democratic gerrymandering while supporting Republican attempts. That’s what I was trying to say above but obviously, I was not clear enough.

In a modern democracy, it’s prudent for the majority not to take too much power because later on the other party (or parties) will be in the majority and have that power available. So you ought to take only such power as you’re willing to give the other side.

Gerrymandering is one such thing. Both parties do it (perhaps not to the same extent). But I wonder how smart it is for either party.

@MarkedMan:

I don’t think it’s a matter of politics on the Court, it’s a matter of how the Justices view the idea that there is or should be a constitutional bar to basing redistricting on party or that there is some provision of Federal law that bars such redistricting. Additionally, I think the Justices will consider the impact that finding a legal limitation on partisan redistricting would mean significantly increasing the caseload of the Federal Courts going forward, something that the Justices are often reluctant to do.

We’ll see.

@Doug Mataconis: Six of one, half a dozen of the other. Do they hold these opinions because they would benefit the Republicans? Or do they favor the Republicans because they hold these opinions? The effect is the same….

@MarkedMan:

One could ask the same question of Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan.

@Doug Mataconis: True. Although my personal political preference is to have Justices that err on the side of protecting the little guy from the big guy, as opposed to the Republican Party Judicial philosophy, “Let ’em burn! They are a lot like cattle, anyway.”

…

https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2019/01/democrats-first-order-of-business-making-it-easier-to-vote-and-harder-to-buy-elections/

@Doug Mataconis:

One could. And one would find that there is an underlying philosophy behind those decisions that is consistent. Liberal, but consistent — based not on which party benefits, but on principles that don’t care who is in power or who benefits.

That’s the key difference. Scalia was a genius, but he used that genius in the defense of his prejudices. There was no underlying consistent philosophy; there was just sophistry in the defense of his biases. Thomas is even worse, not being a genius. He’s a hack, there to defend whatever the GOP favors at the moment without Scalia’s ability to make it sound like there’s a consistent principle behind the hackery. I’m sure Kavanaugh will be even more obvious.

There’s a difference between justices with a philosophy that tends to favor one party over the other, and justices whose philosophy is to favor one party over the other.