The Lack of Competition for House Seats

Yet another reminder of the pathologies of American institutions.

Lee Drutman has a piece at FiveThirtyEight worthy of attention: What We Lose When We Lose Competitive Congressional Districts. It highlights a problem I have frequently noted–that far too many of the 435 seats in the US House of Representatives are linked to non-competitive districts. We know the partisan outcome of those districts well before the candidates are selected, let alone actual elections held.

As Drutman notes in his opening paragraph:

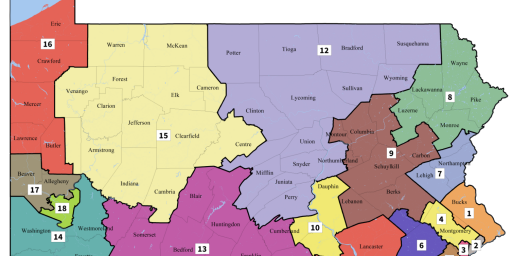

Competitive congressional districts have been steadily disappearing for decades. In the current redistricting cycle, six highly competitive districts in the House of Representatives were drawn out of existence. The Cook Political Report estimates that less than 8 percent of congressional districts will be competitive come November.

Indeed, earlier this week I was doing some research for a piece I was asked to write about the state of democracy in Alabama and it was a reminder that all seven of the state’s districts are highly uncompetitive. The closet margin in the 2020 election was 28.83% in AL01. Three districts (AL05, AL06, and AL07) are so uncompetitive that both major parties did not run candidates.

As a side note, the state’s House delegation is 6-1 R:D. Based on the state’s overall partisan vote that ratio ought to be at least 5:2, and arguably 4:3.

Back to Drutman, who correctly notes

the decline of competitive districts is a problem that reflects deeper causes of partisan polarization and leaves the overwhelming majority of Americans in places where their votes don’t matter, and where parties and candidates don’t need to work for anybody’s votes.

While on the one hand, if a district is 65% R, it stands to reason from a representativeness perspective that the district should be represented by a Republican. But if, as Drutman notes, the votes don’t actually matter as much as the lines on the map do, and if the parties and candidates really don’t have to work to earn the votes, do we have a representative democracy?

Indeed,

when there isn’t competition, citizens and parties have little reason to show up and vote. Instead it becomes the highly organized donors and activists who are engaged, while the rest of the district is ignored.

[…]

the more damaging consequence is how many Americans don’t matter in our elections – and how that drives broader disengagement. In competitive districts, parties and candidates must work to mobilize all kinds of voters for the general election, but in districts where one party dominates — which is the overwhelming majority of districts in the U.S. — this isn’t the case, as whomever wins the primary almost always wins the general election. General elections are a fait accompli, and parties and candidates campaign accordingly.

If all that matters is the primary, then candidates will focus on whatever narrow slice of the electorate they need to win. Under such circumstances, broader representation is irrelevant. And we get the kind of behavior we have seen of late as politicians seek to please the brokers they need to stay in power.

Drutman’s piece discusses several advantages of competitive districts, but his overall assessment is worth re-iterating.

The effects go beyond turnout. Citizens who live in competitive electoral areas tend to be more interested in public affairs. They are more politically informed. They are even more likely to volunteer and be involved in community activity. These markers of healthy civic life decline in uncompetitive districts.

The decline of competitive districts is a real problem for American democracy. With an overwhelming majority of voters living in districts where their general election votes don’t matter, and where parties and candidates don’t have to mobilize any support to win, it’s all too easy for many voters to check out.

I would note that the best way to facilitate competitiveness in US elections would be to shift to proportional representation, such as open-list PR, mixed-member PR, or even RCV in multi-seat districts (i.e., STV). The current system of single-seat districts won’t cut it.

Voters and their votes need to matter if democracy is to have any meaning and having a House of “Representatives” wherein most seats are a function of where lines fall on the map as opposed to how voters vote is a massive problem if one takes the notion of self-government seriously at all.

The lack of political representation (of voters’ preferences and viewpoints) isn’t even the only problem with uncompetitive districts.

It also means that the electorate can’t effectively change its mind.

Which means, in turn, that there is no check on elected officials and representatives.

If you can’t effectively vote elected officials out, they have no incentive to fulfill the people’s mandate. They are free to prioritize their own interests.

That, for instance, is one of the horrifying implications of “a republic, not a democracy.” Land can’t change its mind, which means that those who argue for such a system (in the loose sense of the word) are giving up on one of the fundamental functions of elections: to act as a check on the behavior of elected representatives and officials.

It’s mind-boggling, TBH.

@drj:

Indeed. It is depressing, and what I mean when I often say that the feedback loop is broken.