Who is Publius? or, Who’s Afraid of Anonymous Political Speech?

Reason's Meredith Bragg and Nick Gillespie have a pretty amusing rejoinder to the Obama administration's attempts to smear the anonymous funding of television ads opposed to their agenda in a video titled "Who is Publius? or, Who's Afraid of Anonymous Political Speech?"

Reason‘s Meredith Bragg and Nick Gillespie have a pretty amusing rejoinder to the Obama administration’s attempts to smear the anonymous funding of television ads opposed to their agenda in a video titled “Who is Publius? or, Who’s Afraid of Anonymous Political Speech?”

The transcript:

To hear the Obama administration tell it, there are few things worse than anonymous political activity. Just recently, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius told the Christian Science Monitor:

“The untold story of 2010 is not the “tea party” or not the health-care bill, or a number of these issues. It is the amount of money that is flowing in districts around the country and particularly the amount of anonymous money….

I haven’t been any place where there aren’t dozens of ads now being run and nobody knows who is behind them…I am used to a political system where people engage in battles and you know who brought them to the dance.”

But is anonymous political speech really that new – or that bad?

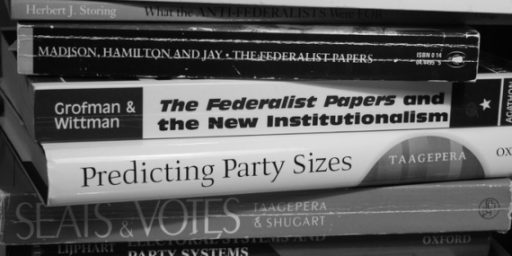

Indeed, anonymous political speech isn’t just a great American tradition. It helped create the United States of America. The Federalist Papers, the series of essays that influenced the adoption of the Constitution, were published under the pseudonym “Publius” (in reality James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay). The anti-Constitution position was in turn articulated by “the Federal Farmer,” whose identity remains a mystery.

Former Federal Election Commission chair Bradley Smith lays out other arguments in favor of anonymous political speech in a contemporary context:

“[Election] disclosure regulations are some of the most burdensome. Disclosure limits free speech because it allows the government to retaliate against people. The Supreme Court has consistently held that people do have a right to anonymous speech. The cases speak for themselves.

The most prominent one is probably NAACP v. Alabama (1964), when Alabama wanted to know who was funding the NAACP’s activities. We can see how that would be intimidating. Then there’s McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission (1995). McIntyre was doing anonymous brochures against a school tax, which all the school officials supported. She had children in the schools who needed grades and access to such things as athletic teams and bands. She didn’t necessarily want her name known, even though it was important for her to fight this issue. Another major case was Brown v. Socialist Workers ’74 Campaign Committee (1982). The socialists rightly said, “If we have to reveal our donors, they won’t give us money. They will get harassed. Their businesses will get blackballed and that sort of thing.” Disclosure can be more inhibiting than people think.”

Which is something to think about when people already in power push legislation such as The DISCLOSE Act, which would force groups to list donors and reveal their names in advertisements. The DISCLOSE Act is in part a response to this year’s controversial Citizen’s United v. Federal Election Commission ruling by the Supreme Court. Hyperbolically likened by critics to the infamous Dred Scott decision, Citizen’s United dealt with a documentary film censored by the government and broadened the speech rights of corporations, unions, and nonprofits. Far from opening American politics up to undue influence by unspecified foreigners (as President Obama has charged), the ruling makes it easier for smaller groups and individuals to spread their messages.

As with many political firestorms, the current one about “dangerous” anonymous speech generates more heat than insight. Anonymous speech is fully in the American grain but it also comes at a price. When the source of political speech is not known or disclosed, voters tend to discount it, or at least look for corroboration elsewhere. Which is exactly how it should be. And if you don’t in the end trust voters to make informed decisions, then all the mandatory disclosure in the world can’t help them.

Indeed.

Now, in principle, I tend to favor disclosure. But speech should ultimately stand on its own merits. That “Publius” was really James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay is an interesting historic footnote. But it doesn’t add or detract from the persuasive power of the Federalist Papers.

Is there any downside to full and complete disclosure of funding for political ads? Other than it possibly being impossible to know, of course. You say that words should stand on their own, but that corroboration is sometimes sought; what if corroborating sources can trace their roots back to a common parent? Wouldn’t that be useful to know? In general, I suspect you’re underestimating the power of propaganda and messaging if you think words stand on their own merit, end of story. (But I could be wrong, etc. etc.)

Given that the papers were written under the guise of a fellow New Yorker, and Madison was from Virginia, I think knowing who was behind them would have had some impact on it’s reception.

Course, in the end Publius didn’t manage to convince New York to vote for the new Constitution anyway, so maybe it wouldn’t have made much of a different.

The real truth here is that money is not exactly equal to speech.

If any other billionaires(*) are posting here under anonymous names I have no problem.

But you know, any one of us dropping $100,000,000 on TV is a bit different.

If the law doesn’t get that truth now, it needs adjustment.

* – joke