Why Moral Persuasion is So Hard

As noted in Friday’s podcast recommendation, I enjoyed Julia Galef’s conversation with social psychologist Jonathan Haidt on “Understanding moral disagreements.” The audio and a PDF transcript are available at the link but the discussion introduced me to Moral Foundations Theory, of which Haidt is a key developer.

As he introduced it in the interview:

A lot of psychologists have used the metaphor of language: Language is

universal, but languages differ. But I found that the metaphor of taste

works better: So, we all have the same taste buds on our tongue with

sweet, sour, salt, bitter, and umami, which is a meat flavor. But our

cuisines differ around the world. This, to me, has been the most fruitful

metaphor.So the question is what are the taste buds of the moral sense? By just

looking at what are the places where there’s an existing evolutionary

theory, and it shows up in lots of cultures — what are those connections?

His original “taste buds” were “fairness versus cheating, loyalty

versus betrayal, authority versus subversion, [and] sanctity versus desecration.”

As summarized on his website:

[T]he theory proposes that several innate and universally available psychological systems are the foundations of “intuitive ethics.” Each culture then constructs virtues, narratives, and institutions on top of these foundations, thereby creating the unique moralities we see around the world, and conflicting within nations too. The five foundations for which we think the evidence is best are:

1) Care/harm: This foundation is related to our long evolution as mammals with attachment systems and an ability to feel (and dislike) the pain of others. It underlies virtues of kindness, gentleness, and nurturance.

2) Fairness/cheating: This foundation is related to the evolutionary process of reciprocal altruism. It generates ideas of justice, rights, and autonomy. [Note: In our original conception, Fairness included concerns about equality, which are more strongly endorsed by political liberals. However, as we reformulated the theory in 2011 based on new data, we emphasize proportionality, which is endorsed by everyone, but is more strongly endorsed by conservatives]

3) Loyalty/betrayal: This foundation is related to our long history as tribal creatures able to form shifting coalitions. It underlies virtues of patriotism and self-sacrifice for the group. It is active anytime people feel that it’s “one for all, and all for one.”

4) Authority/subversion: This foundation was shaped by our long primate history of hierarchical social interactions. It underlies virtues of leadership and followership, including deference to legitimate authority and respect for traditions.

5) Sanctity/degradation: This foundation was shaped by the psychology of disgust and contamination. It underlies religious notions of striving to live in an elevated, less carnal, more noble way. It underlies the widespread idea that the body is a temple which can be desecrated by immoral activities and contaminants (an idea not unique to religious traditions).

We think there are several other very good candidates for “foundationhood,” especially:

6) Liberty/oppression: This foundation is about the feelings of reactance and resentment people feel toward those who dominate them and restrict their liberty. Its intuitions are often in tension with those of the authority foundation. The hatred of bullies and dominators motivates people to come together, in solidarity, to oppose or take down the oppressor.

Interestingly, while most people and cultures share these foundations, they emphasize them differently. Of particular interest to me is Haidt’s contention that,

The current American culture war, we have found, can be seen as arising from the fact that liberals try to create a morality relying primarily on the Care/harm foundation, with additional support from the Fairness/cheating and Liberty/oppression foundations. Conservatives, especially religious conservatives, use all six foundations, including Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, and Sanctity/degradation. The culture war in the 1990s and early 2000s centered on the legitimacy of these latter three foundations. In 2009, with the rise of the Tea Party, the culture war shifted away from social issues such as abortion and homosexuality, and became more about differing conceptions of fairness (equality vs. proportionality) and liberty (is government the oppressor or defender?). The Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street are both populist movements that talk a great deal about fairness and liberty, but in very different ways, as you can see here, for the Tea Party, and here, for OWS.

Haidt fleshes this out in considerable detail in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion and provides a full copy of Chapter 7, “The Moral Foundations of Politics,” on the site.

So, why does that matter? Haidt argues that, because people from different cultures and subcultures emphasize these foundations differently, it’s exceedingly hard to have moral arguments with those in other groups because “people use words, and we each think we understand what the other person means because we use the word, but often they mean something very different.”

And this comes down to humans simply being less rational than we like to think?

Intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second.

Second principle is there’s more to morality than harm and fairness,

which we already talked about.And the third principle is “morality binds and blinds.” And this is just a

thing about humans, is that we like to make something sacred. We circle

around it, then we worship it together and then we can’t think clearly

about it. And we get mad at people who say true things about it.

To be clear, he’s not arguing that liberals (like himself!) are less morally developed than conservatives. Rather, he’s trying to understand why their appeals are less effective:

[Liberals] have the receptors, they can have the feelings, but they don’t couch their arguments in those terms. And that’s what I was trying to convey in The Righteous Mind, that all around the world, at least in the Western world, the left tends to underperform politically because they don’t make appeals on these foreign… They leave, they cede a lot of the moral landscape to conservatives.

So when there’s a surprise, when there’s an electoral surprise, how often is it the case that you wake up in the morning and, “Oh, surprise, the left

swept everything.” No, that almost never happens. When there’s a

surprise it’s usually, “Oh my God, Brexit passed. Oh my God, Trump got

elected. Oh my God, this neo-Nazi just almost won the…” Whatever. It’s usually the case that the right surprises, because most people have these

concerns, they build on these moral foundations, but left leaning parties

tend not to address them.

He cites research that has “shown that if you ask people to make an argument to the other side, they make it in their own preferred moral foundations, and they’re not persuasive. But if you teach them about moral foundations theory and you say, “Now try to make an argument for environmental policy or whatever using loyalty, authority, or sanctity,” they can do it. And then they’re more persuasive.

He references the novel Flatland by Edwin Abbott, written way back in 1884. The Wikipedia plot summary:

The story describes a two-dimensional world occupied by geometric figures, whereof women are simple line-segments, while men are polygons with various numbers of sides. The narrator is a square, a member of the caste of gentlemen and professionals, who guides the readers through some of the implications of life in two dimensions. The first half of the story goes through the practicalities of existing in a two-dimensional universe as well as a history leading up to the year 1999 on the eve of the 3rd Millennium.

On New Year’s Eve, the Square dreams about a visit to a one-dimensional world (Lineland) inhabited by “lustrous points”. These points are unable to see the Square as anything other than a set of points on a line. Thus, the Square attempts to convince the realm’s monarch of a second dimension, but is unable to do so. In the end, the monarch of Lineland tries to kill A Square rather than tolerate his nonsense any further.

Following this vision, he is himself visited by a three-dimensional sphere. Similar to the “points” in Lineland, the Square is unable to see the sphere as anything other than a circle. The Sphere then levitates up and down through the Flatland, allowing Square to see the circle expand and retract. The Square is not fully convinced until he sees Spaceland (a tridimensional world) for himself. This Sphere visits Flatland at the turn of each millennium to introduce a new apostle to the idea of a third dimension in the hope of eventually educating the population of Flatland. From the safety of Spaceland, they are able to observe the leaders of Flatland secretly acknowledging the existence of the sphere and prescribing the silencing on. After this proclamation is made, many witnesses are massacred or imprisoned (according to caste), including the Square’s brother.

After the Square’s mind is opened to new dimensions, he tries to convince the Sphere of the theoretical possibility of the existence of a fourth and higher spatial dimensions, but the Sphere returns his student to Flatland in disgrace.

[…]

The Square recognises the identity of the ignorance of the monarchs of Pointland and Lineland with his own (and the Sphere’s) previous ignorance of the existence of higher dimensions. Once returned to Flatland, the Square cannot convince anyone of Spaceland’s existence, especially after official decrees are announced that anyone preaching the existence of three dimensions will be imprisoned (or executed, depending on caste). Eventually the Square himself is imprisoned for just this reason, with only occasional contact with his brother who is imprisoned in the same facility. He does not manage to convince his brother, even after all they have both seen. Seven years after being imprisoned, A Square writes out the book Flatland in the form of a memoir, hoping to keep it as posterity for a future generation that can see beyond their two-dimensional existence.

Essentially, Haidt argues, people like Julia (and myself), who attempt to understand the world through empirical observation and application of reason are squares living in a three-dimensional world. While Haidt himself is largely in agreement with her (and me) on how we should govern, he makes some significant modifications to compensate for the fact that most people have those other dimensions and simply need sanctity, authority, and the like to thrive.

People, human beings, the way we are, we crave meaning. We tend to

infuse meaning in things. We need groups. We thrive in groups. And we

sometimes lose sight of these facts, especially people who are rationalist

or libertarian.In fact, the idea that I’m proudest of in The Righteous Mind, which

nobody has ever referred to other than me, is what I call Durkheimian

utilitarianism. That is, if we’re going to do public policy, if you’re going to

look for what should the laws be based on in the United States or in the

state of New York or whatever, ultimately, if you’re a legislator, there is no basis other than consequentialism. […] So that’s the utilitarian part, but the problem is that utilitarians tend to not understand that people need these ties. They need irrational things. They need either religion or something like religion.

Even though he’s a liberal Jewish atheist, his solution is rather conservative. To oversimplify, it’s local control, so that people in red states and rural areas can be governed according to their morality and those in blue states and big cities can be governed according to theirs. (He doesn’t really address how to reconcile the overarching role of the national governement but, really, that’s outside the scope of the conversation.)

While I’ve seen bits and pieces of all of this before, putting it together in one place—particularly in the context of the last five years or so of American politics—helps clarify a lot of frustrations I’ve had discussing politics with both the OTB commentariat who are more organically liberal than me and Army and high school friends on Facebook who have remained much more conservative.

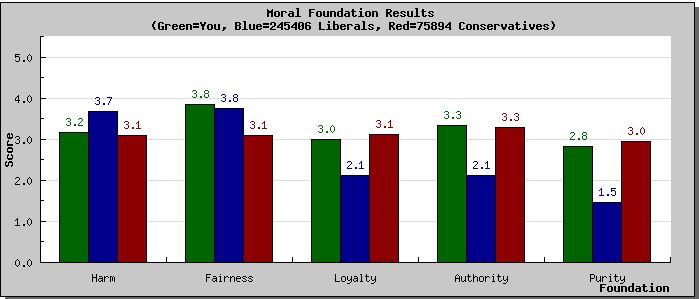

I took Haidt and company’s moral foundations quiz, with which I have some quibbles, and mapped this way:

I’m closer to conservatives on four of the five dimensions but exactly matched with liberals on the fairness dimension.

To some degree, that’s not surprising. I grew up as the son of a career soldier, spent my young adulthood as a cadet and Army officer, and have spent the last 7-1/2 years teaching at the Marine Corps’ staff college. And I’ve lived exclusively in the South (if you include Texas) or military bases my entire life.

On the other hand, I’m an academic by training and a rationalist by temperament. While I still technically live in the South, I’ve been in the deep blue Northern Virginia suburbs of DC for close to twenty years now. And my policy preferences have shifted significantly to the left (albeit almost certainly owing to engaging in policy debates here and elsewhere vice geography) over that period.

This would intuitively seem like an advantage. I’m not a Flatlander at all but rather a would-be rationalist who scores very high on all five of the measured dimensions. But rationalist arguments don’t work well with conservatives and, while I’m in many ways a traditionalist, I’m not religious. Meanwhile, liberals tend to simply reject arguments from tradition, loyalty, and sanctity as prejudice.

I need to think about this more. But this is beyond the cognitive psychology literature that people tend to have various anchoring biases that lead them to seek confirmation of their priors.

I’m not gonna try to be diplomatic. Haidt is hot garbage.

His moral foundations theory, totally objectively of course, shows that conservatives are more caring and decent people than liberals. Those six points have been constructed that way, perhaps not deliberately, but they have no foundation in anything but Haidt’s mind.

He got a lot of attention several years back, and then psychologists and sociologists started looking at what he’s doing analytically. He’s a Professor of Ethical Leadership at a business school, which should be a clue.

Sorry you’re coming to this late, James. He has a few good points, but his overall outlook is conservatives good, liberals bad. Everything he does revolves around that.

Whoa, hold on here, I am hard pressed to see conservatives in this:

Self sacrifice for the group? The people who define IGMFY?

@OzarkHillbilly:

He might be thinking of conservatives like Angela Merkel rather than Ted Cruz. American conservativism is an anomaly (and probably shouildn’t be called conservative, in that they don’t seem to be actually trying to conserve anything — they’re trying to pull America back to at least the 1950’s, and possibly the 1850’s).

@Cheryl Rofer: yeah, this stuck out to me:

I recall reading about Haidt’s theory some time ago, and it stating that liberals scored highly in two areas, care/harm, and fairness. But now his fairness category no longer involves equality, so liberals aren’t even moral in that area anymore…

Thank you for signal boosting Haidt and his work. He is an important voice, and his approach to engaging in vexing societal challenges should be emulated, not derided. He deserves better than to be labeled “hot garbage.”

Does MFT have problems? Yes. It falls short on theoretical and empirical grounds. Re the former, it lacks a deeper theoretical foundation, which Haidt and colleagues acknowledge. I won’t go into the weeds, but this lack of grounding has important downstream effects. Re the later, empirical support for MFT has been spotty.

But one of the things that I appreciate most about Haidt is his willingness (nay, seeming enjoyment) to engage directly and fairly with these limitations of his model. He puts himself out there, in writing and otherwise (interviews, podcasts, panels, etc). Indeed, there’s an entire section on his website that outlines the critiques to MFT (again, with fairness). We need more of this, and we should applaud it, not sneer at it.

The old adage of “all models are wrong, some are useful” is particularly apt when it comes to MFT. As James wrote: “[it] helps clarify a lot of frustrations I’ve had discussing politics with both the OTB commentariat who are more organically liberal than me and Army and high school friends on Facebook who have remained much more conservative.”

For those who are interested in thinking about their discourse with others and trying to make inroads on this front, you might also consult Kling’s the 3 Languages of Politics. It’s a kissing cousin to MFT, with a focus on, well, language. Cliff notes version: Progressives communicate along an oppressor–oppressed axis; Conservatives communicate along a civilization–barbarism axis; Libertarians communicate along a liberty–coercion axis.

Is this a perfect model? No. Is it useful? My experience says yes. YMMV.

@Mimai:

Other than that, it’s pretty good.

When someone continues to push something that is obviously biased, he falls into the category of “hot garbage.”

@Cheryl Rofer: Show me a (social science) theory that is airtight on both those fronts. Perfect, good, enemies, and all that.

I don’t think it’s fair to imply that he has dug his heels in vis-a-vis the model. Indeed, he’s made substantive changes along the way…..in response to critiques and data. And he continues to engage in good faith.

Perhaps you and I have different definitions of “hot” and/or “garbage.”

@Cheryl Rofer:

I vaguely remember some of the debates around this five or six years ago but it didn’t really pique my interest. But

is very much a straw man. Indeed, he’s a liberal trying to figure out why liberals do less well at the polls than he thinks they should.

@OzarkHillbilly:

Part of the problem is that you’re defining the group differently. But, yes, sacrifice is inherently part of an honor culture. It’s why military service is so highly valued in conservative circles.

@Mimai:

Yes.

I think another thing that often challenges this discussion (of MFT or any moral theory) is the failure to consistently distinguish between moral foundations (organizational frameworks) and behavioral reality.

Another challenge is to disengage from one’s own narrow perspective (ie, current definition of “conservative” or “liberal”) and to think more broadly (in scope and time horizon) about these (fuzzy but still useful) categories.

@Mimai: So many parentheticals.

@Mimai:

I read The Righteous Mind a number of years ago and while I found it interesting, the problems you note have made it difficult for me to take it especially seriously.

And I am not asking for such a framework to be airtight, but I if a model has a spotty record in terms of empirical support, it is hard to fully take it seriously.

Again, it has been a while since I read the book, but I think while it does note some notions worthy of consideration (such as that humans tend not to use rationality first and that there are different frameworks, such as what James notes in the OP that filter reason), I am not convinced it provides a real model.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I’m actually more interested in the takeaways than the model itself. Regardless, Haidt and his various collaborators agree that it’s a tentative, evolving framework. They’re rather generous in listing and responding to critiques, although it appears they largely abandoned that in 2016. Regardless, their preable seems reasonable:

As best I can tell, I don’t think Haidt himself thinks his work shows “conservatives are more moral”. That’s not how I understand it myself. Others may have used it that way, though.

In a sense, though, that’s a sideshow to the thesis of the OP, which is to ask “what kind of arguments work well?” I think that’s really important and valuable.

I think Haidt is describing the emotional landscape, which differs across the population. Some kinds of arguements bring forth more emotion. They elicit a stronger response. This is the territory of emotion, not moral behavior.

James is a rationalist, and so am I. However, I have learned that I am a rationalist because it makes me feel good. That is, even in a hard-core rationalist like myself, emotions are the fundamental driver of personality. Different kinds of arguments have more or less emotional impact, and it’s valuable to understand what the strongest concerns of the person you are trying to convince might be.

I still need to listen to the podcast, so this might be addresses there, but a problem I find with these types of framings is the failure to account well for issues of power (and the perceived loss of it). This also ties into some of what Steven explored yesterday in his post on race.

The problem with developing something that you call “Moral Foundations Theory” is that it puts the developer in the position of objective observer or on the side of good. Because why would you develop such a theory if you were on the side of evil?

That’s not a claim about Haidt’s viewpoint. That’s inherent in the structure of the project.

I haven’t followed Haidt since I looked at his claims, as did Steven Taylor, and found them seriously wanting. Life is too short. I know that he ostensibly replies to his critics, but I don’t know the quality of the replies. I’ll continue to believe that he hasn’t changed much since I stopped looking.

I know he presents himself in such a way as to allow you to believe he’s a liberal, but when all his conclusions come out as conservatives being more moral, decent people, well…

A”moral” project leads to “us good, them bad.” Takeaways from a seriously biased project will be seriously biased. If you want to look at “thinking fast and slow,” go back to Daniel Kahneman, who developed it without Haidt’s moral overlay.

Read The Righteous Mind many years ago. My recollection is that it was interesting but seemed somewhat forces and not terribly explanatory. I have a recollection, perhaps confused with someone else, that he went to a lot of trouble to shoehorn libertarians into his scheme in such a way that led me to suspect he are one. This seems consistent with his tentative sixth foundation, liberty/oppression.

The explanations of Haidt’s foundations James quotes above relies on evolutionary psychology. I’m not sure evolutionary psychology is well regarded, but I recall thinking at the time that that his five foundations made sense in a tribal society. But the last three (of the five basic) foundations were perhaps maladapted to modern life in a large democracy. How much do I have to worry about purity in a world with the FDA and use by dates? And it’s easily turned into hatred of outgroups and a desire to build a wall.

Is it so much that liberals don’t communicate in terms of the last three foundations or that it’s so much easier for conservatives to twist them to their ends?

MFT falls in the same category as Myers-Briggs type theory to me. No scientific grounding at all but a useful reminder for me to consider aspects of someone’s motivation that I might otherwise gloss over because those motivations aren’t important to me.

I can’t find the reference at the moment, but I read some commentary by Haidt somewhere that although conservatives tend to use all 5 foundations, they lean most heavily on authority and sanctity. That made a lot more sense to me. Liberals, in the extreme formulation, don’t think morals should be grounded on things like sanctity at all, while conservatives agree that care is a grounding for morality, just not the most important one. So when care conflicts with authority, they go with authority.

Oh good, we’re building a system to explain human behavior. That always works.

Yeah, people who insist on only seeing what actually exists are such squares.

Right: Jim Crow and compulsory attendance at the nearest Southern Baptist church. That’ll fix everything.

Yes, we do tend to reject those ‘arguments’ because they aren’t ‘arguments’ they’re just assumptions – assumptions that by their nature are invulnerable to analysis or criticism. I mean, if The Lord says beat my wife, what am I gonna do? Not beat my wife? It’s right there in the Bible! Authority! Sanctity! Self-serving bullshit!

As to the matter of liberals failing to convince, a very short list:

Social Security

Medicare

Rock and roll

Long hair

Cohabitation

Marijuana

Gay marriage

Trans rights

We’ve won every social issues battle. Probably because we’re squares lacking the multi-dimensional nuances of. . . No, sorry, not wasting more time on this Cosmopolitan level personality quiz.

@James Joyner: I think that Haidt raised issues that are worthwhile–in simple terms bring to the fore the notion that rationality is not as central as we think it is and that there are ways in which different types of people use different frameworks to filter their rationality.

I do object to the notion that it is a “theory” and I think part of my discomfort with Haidt is the more I have been exposed to him he feels more like a pundit (or even a “guru”) than a social scientist.

I also have gotten the sense (and it is just a sense) that in the last several years he has become one of the “liberals” that certain kinds of conservatives love because he criticizes liberals more than he criticizes conservatives (but that sense may be unfair).

I don’t want to discount the heart of this post: that we need to understand how different people think through problems. But I have cooled on the notion that Haidt provides more than a help to get us to think differently but doesn’t provide much more than that starting point.

The whole theory seems to built around many things that exist only in the heads of very conservative Americans. Conservatives really must believe that liberals are like, “Well that marriage fell apart after 15 years, nbd, I’m not devastated at all and certainly do not feel as I have utterly failed as a human, because I don’t have to answer to God and the Bible and Jesus.” Or that the billions of yoga studios and crank health food boutiques in blue cities aren’t testaments to an idea of sanctity. I mean, it’s like not going to some strip-mall church in a super-large pickup truck, which is as God intended.

The larger question as to why persuasion between liberals and conservatives is difficult is due to conservatives having tied themselves to a morality that doesn’t make any sense, even to them. There’s a question on that quiz about chastity. Honestly, chastity. Does anyone marrying the first person you want to have sex with is a great idea?

@Steven L. Taylor: yes. And he is one of those “academic dark web” heterodox academy guys who seems to think that the more people criticize his ideas the more right they must be. Because “you can’t handle the truth” or something.

@Steven L. Taylor: I agree with everything you write. I am not an advocate for MFT per se. I find these MFT and related theories to be most useful at the meta level. That is, they help me to think more broadly about the issues and, thereby, engage in more productive discussions (with myself, my dog, and other people). Perspective-taking is hard. These formulations help.

@gVOR08:

This pegs a memory of what I find problematic about the book. It seemed predicated on the notion that we reason as we do due to evolution, but I never understood why this led to conservatives and liberals (and it is a bit too pat that this American divides all into those categories).

I also never understood how his framework accounts for people changing the way they think over time.

Again: I am quite open to the thesis that humans are not nearly as rational as we think we are (even those of us who try to be rational). But I find the ready-made explanation for American politics, in particular, to be too pat (and I do seem to recall he did have some non-US stuff in the book, but I can’t recall for sure).

@Cheryl Rofer:

Thank you for articulating this. It helps me understand how you are engaging with this topic. And why we seem to be talking past each other. And why our discussion seems so unproductive.

@Jay L Gischer: this I can agree with (and I think George Lakoff has also covered this territory):

@Mimai: I see nothing in this discussion that is different from what I learned about Haidt earlier. Please explain where he’s changed.

@Cheryl Rofer:

I’m a huge fan of Kahneman’s work but also agree with Haidt’s argument that “Cognitive psychology is social psychology with all the interesting variables set to zero.”

It’s the difference between classical and behavioral economics. Both are useful at answering different questions but the former ignores a lot of questions the latter does a better job of answering.

@Mimai: I can relate. (Sometimes I think most of my thoughts are parenthetical)

@Steven L. Taylor: His short answer, via the interview, “The moral mind is a product of evolution, but yet it develops differently in different cultures. So how do you reconcile that?” I think he’s legitimately trying to answer a question rather than retrofit questions to a pre-existing belief system.

@Cheryl Rofer: I am not inclined to detail for you all the ways he has changed. In part, because I don’t know what you consider to be T1. And in part, because, as you say: “Life is too short.” Haidt is a prodigious writer and speaker, and is active on social media. He even has a youtube channel. He’s not exactly hard to find. The google wizard can guide you much more effectively than I can.

@Steven L. Taylor:

That’s fair. I read his analysis as less charitable to conservatives than Cheryl and others, in that I think he’s genuinely trying to do analysis rather than providing value judgments. It may well be that the disgust variable is a bad way to form moral opinions—indeed, Chait seems to think so as well. But, if a significant part of the polity does that instinctively, we have to account for it in our discourse.

Indeed, I think a significant part of the problem with our debate over homosexuality and transgender issues is that cultural conservatives simply reacted to those things are disgusting (and therefore unclean/immoral) and that no amount of argument about fairness was going to overcome that. People changed their minds only once they got to the point where they saw homosexuality as something that non-icky people were hard-wired to do. We haven’t gotten there yet on trans issues and calling people who think transitioning male-to-female transgender folks are disgusting “its” bigots may make us feel better but hardens, rather than moves, the discourse.

Politics is, first, about keeping people from killing each other. And second, and at its best, finding a means to advance the common good without the use of force or enforced orthodoxy – when people don’t even agree on what the common good is.

Many, many people have opinions and world views different than me. Whether Haidt is liberal or conservative or something else doesn’t matter to me. Is his data good and scientifically rigorous? And is it useful?

I can’t speak to the first, but it seems to me that the second is a “yes”. When I train mid-level managers on how to present their projects to an approval committee, one of the most important things I try to get them to do is to find out who is on that committee, think about each one individually and strive to understand their viewpoint and how they will view your project. For those already favorable, briefly reinforce the facets that appeal to them. For those who might actively oppose, figure out why and attempt to find ways that your project might advance their goals and highlight those. But leave the all too human desire to get people to care what you care about outside the door of the meeting room. You don’t need them to think like you, you just need them to support, or at least not oppose, you.

To paraphrase Hillary Clinton, if you want to change the world, f*ck winning hearts and minds. Change the laws. That’s what will make a difference in someone’s life.

One other foundation to consider throwing into this: universality. One big variation in morality from one culture to another is who “morality” applies to. Just the family? The “tribe”? The “nation”? All of humanity?

People changed their minds only once they got to the point where they saw homosexuality as something that non-icky people were hard-wired to do.

I think the overall point Steven is making is that there’s no evidence that people are hard-wired to respond to political issues. Certain people may be more hard-wired to be grossed out. But doesn’t mean they are grossed out by gay people. They may find racism or bigotry revolting. You are taking a social construct and immediately assuming that it must exist due to evolutionary hard-wiring.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I’d like to focus in on the “pundit” part, as I think the “guru” label is pejorative and unfair.

Do you consider “pundit” to be a category or a spectrum?

What are the necessary and sufficient characteristics?

How do you distinguish between “pundit” and “science communicator”? (can replace “science” with any scholarly domain)

Is Neil deGrasse Tyson a “pundit”?

I don’t expect answers to these questions. Rather, I ask them to try and get a better idea of how you think about “punditry” in this context (outside the typical political context where it seems more clear).

I’ll just add that enormous numbers of people are fat-phobic and find fatness disgusting. Is that hard-wiring? Are women hard-wired to hate their bodies and to strive for thinness that would be considered unnatural 100 or 200 years ago? Or is disgust a basic part of human behavior that conservatism (amongst other things) has tapped into a way that liberalism hasn’t?

First of James, thanks for this most interesting post. This is right up my alley and is a topic I’m deeply interested in. It’s also a nice break from the usual political and culture war fare, but still related in an interesting way.

Just to give some background, as part of my training and education to become (and become a better) intelligence analyst, I studied a lot of cognitive psychology. In the intelligence community, understanding how humans think is (or at least was) necessary to do the job well. It’s been a professional interest for serious analysts going back to the 1950’s because of how often analytical misjudgments came from cognitive limitations of the human brain and not from a lack of information. Errors in intelligence tend to get a lot of focus because, unlike culture war debates on blogs or Twitter, misjudging the motivations of an adversary due to insufficient introspection and analysis is what gets people killed and even nations destroyed.

Anyway, I’ve followed Haidt’s work and applaud him for attempting to develop an explanatory model for human behavior in order to improve communication and understanding regarding our differences. That is certainly a more admirable pursuit, IMO, than the usual “your side bad, my side good” tribalism that permeates just about every aspect of the commanding heights of our culture these days.

But none of what Haidt offers is really new. Haidt is just one of the latest in a long line of curious and smart people who have tried to crack the code of the human mind. I think he’s got some interesting insights and he’s repackaged it a new and approachable way. Also, I think a discussion that forces or incentivizes people to engage in more introspection about their own thought processes is always useful. But ultimately Haidt has not come up with the Grand Unified Theory for cognitive psychology and human behavior. That’s not a criticism – no one has and it’s a wickedly difficult problem as Flatland demonstrates.

Again, most of my education is related to intelligence problems (military conflict and international politics) but the principles are basically the same for discussions about why people are generally so bad when it comes to actually understanding and characterizing adversaries from other political or cultural tribes.

If you haven’t already, I’d highly recommend you read Heuer’s “Psychology of Intelligence Analysis.” It would also be useful to your students as it doesn’t just apply to intelligence problems. It’s been published in unclassified book form for many years, is free online at the CIA website, and is based on a series of papers written internally for CIA analysts in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. I think if you spend the time looking at this (it’s not a long read), you’ll find that Haidt doesn’t offer much that is truly novel. Again, that’s not a hit on Haidt, it’s just the field hasn’t progressed much in a very long time and is very derivative at this point.

Here’s a taste from Heuer:

You can replace “China” with “Republicans” or “Democrats” or whatever shorthand people use to conglomerate together groups of people they view as adversaries.

@Cheryl Rofer:

I don’t think his theory shows what you’re suggesting at all. He’s attempting to use different moral axes to explain views and behavior, not to make value judgments about different groups. I agree that his model has deficiencies, but I think your conclusion that it somehow suggests liberals are less moral and decent is not at all accurate. The fact that liberals and conservatives will plot different on these axes is neither surprising nor indicative of who is “better.”

The entire point is that subjective views about what is perceived as caring or decent are…subjective.

@Modulo Myself:

You are right to make these distinctions. I believe the argument is that people are “hard-wired” to have certain emotional reactions. And these are universal. But the social (or political if you will) context determines the object that elicits these reactions, as well as their expressions.

I’m trying to think of a time when liberals have made an argument along these lines that was effective. All I have is John Stewart telling the Crossfire folks that they are hurting America, and those shows imploding immediately after.

(Aside: and now, we have unadulterated bullshit… better?)

Every other time, it’s just been ignored. Environmentalism, proliferation of unadulterated bullshit in the right wing media, Donald Trump has no class, etc. it hasn’t changed minds.

@James Joyner:

Exactly. Once people have formed a life view it is extremely difficult to get them to change their mind about what’s important. I suspect Ellen and Tim Cook and that gay couple on Barney Miller had a lot more impact on gay rights than we give them credit for, just by their mundaneness. If someone’s worldview is based on naturalness vs unnaturalness, it’s a waste of time arguing about fairness. The right wing hysteria machine gets this. When they lost the “ick” factor on gay marriage, they were lost because all they had left was, “if gays get married it will lessen your ‘normal’ marriage”, and enough people recognized that as a stupid argument that they lost the game. So their new focus is on bathrooms and showers. It’s a stroke of genius because now what the trans person is doing really does literally invade your, or your kids, space. For someone deep in the natural/unnatural world view it’s going to be hard to get past.

Appeal to fairness isn’t going to go far with that crowd. I think a much more effective argument would be to deke to the right and put the wingers on the defensive. “You know, now that you mention it, this whole thing where we take pre and post pubescent kids and make them shower together in a big group is really strange in this day and age. Why are you so intent on preserving that? What the hell is wrong with you?”

@Gustopher:

Anti-GMO and left-wing parts of the anti-vaccine movements. While they often try to frame it as a care/harm issue, it’s really driven by an idea that genetic manipulation or vaccines are “unnatural” and that introducing them to the body defiles it with impure synthetics.

@Andy:

Forgive me for focusing on one tiny part of your thoughtful post, but this is something that I noodle quite a lot. It seems to me that “we” overly privilege the new/novel/innovative etc. And we don’t give nearly enough credit (or status) to people who take “old” ideas and package them in compelling, digestible, and, yes, new ways.

That is all….back to the very interesting discussions.

@Steven L. Taylor:

IIRC Prius or Pickup talks about there being no necessary connection. (“I created a psych questionnaire and a scale and from that a philosophy of life.” seems a prolific genre.) Many Republicans come from a corporate background where manipulation through advertising is a science. They seem to effectively use Haidt’s “foundations” or whatever as hooks to manipulate the electorate. Authority, purity, and loyalty would lend themselves to us v them appeals.

@Mimai:

The brain is obviously ‘hard-wired’ to develop a self. The dullest parents can raise a kid who by 3 will be a person with a dizzying number of emotions. How these emotions grown and form into those of an adult person is beyond, right now, science to explain in a way that Haidt is trying push, in my opinion.

Overall it seems strange to me not to believe that humans are hard-wired to learn and adapt and change. At the same level, there are people who can pick up snakes without shuddering. I’m not one of these people and no way will I ever be one, unless something happens to my brain.

@Steven L. Taylor:

IMO the short answer is that is how tribal psychology works. Brink Lindsey in an essay I keep bookmarked put it this way when talking about partisans and partisan identity:

@Stormy Dragon: @Gustopher: I think there’s also a hint of the sanctity in discussions about reclaiming “black bodies” which have been degraded throughout the course of American history. You see this a lot in the writings of Coates. To be sure, I don’t think it’s the primary theme, but I do think it’s there.

In fact, it can be seen as a way of taking back (over?) the language that has been heretofore used as a cudgel against them. To wit, racist conservatives (please don’t @ me about that) have often framed discussions of race around notions that Black people are primal, carnal, and base. This is what it means to dehumanize.

So by reclaiming the “black body” and imbuing it with nobility, sanctity, and reverence, liberals (and other antiracists) are engaging the sanctity dimension. Now whether you find this to be effective is a matter of opinion. But it sure seems to have gained some traction in the discourse.

@MarkedMan:

And yet, for the segment of the population for whom “if I don’t like you, you’re bad” is the guiding principle of life, “f*ck winning hearts and minds” get us, well… Donald Trump, for example.

Balance in everything to the degree that you can achieve it.

@Andy:

And the reason is that people start with political identities and then move to opinions about how the world works, not vice versa.

This is actually saying the opposite of what Haidt’s theory says. Haidt’s theory says that are different inherent moralities which end up being labelled conservative or liberal. Brink Lindsey says that there is no epistemologically sound reason to have morality other than a priori tribal partisanship.

@Steven L. Taylor:

This.

Pundits generate hot takes. Hot takes generate revenue.

Scholars generate careful, circumscribed research. If a scholar generates a take at all, it is rarely hot.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: I get what you are saying and it is valid. This comment is more directed to those who were saying, for example, that it is “too soon” for gay marriage or 1950’s era civil rights because “the country is just not ready”. The day the Supreme Court upheld gay marriage, no one could be barred from their spouses bedside regardless of where Nurse Ratched’s heart was at.

@Andy:

It isn’t that I don’t see how it would lead to tribes being formed. It just the approach seems too amenable to American circumstances just to be about evolutionary psychology.

At a minimum it suggests other social variables are important as well.

@Modulo Myself:

This is kind of where I fall when I evaluate moral frameworks. No matter what, it seems like philosophers are working backward from some other preference.

I think it’s impossible to look at the history of thought and conclude that a moral framework can be independent of culture.

@Kurtz: I’m hard-pressed to see an Ivy PhD who was elected to the most prestigious fellowships and made full professor at a top tier school (Virginia) as a relatively young scholar as not a scholar.

@Andy: I will take a rare opportunity to agree with Andy 😉 and note that a lot of people in this thread seem to be mistaking a descriptive theory for a prescriptive or normative one. Haidt is saying “people factors these six kinds of things into their moral judgements, and different people give the six dimensions different relative weight. Those different relative weights can explain why people who think they are both concerned with morality can nevertheless disagree strongly on particulars.”

I had to laugh when James said:

…because it would never have occurred to me to read Haidt as implying any such thing. He was diagnosing the source of disagreement, not picking sides, at least in the quoted bits. “Taking more things into account in moral arguments” is not obviously a good thing. If some hypothetical group were just like liberals, but cared deeply what color things were painted, we would not say that they are therefore “more morally developed”.

I laughed again when James wrote:

…which completely misses the point that it’s the ranking of criteria that matters, not the absolute scores.

Liberal priorities:

Fairness

Harm

(big gap)

Loyalty and Authority equally

(big gap)

Purity

Conservative priorities:

Almost equal weighting of all six, with Authority slightly the most important and the others essentially equal. (Ranking “Authority” above all other dimensions is literally incomprehensible to liberals.)

James’s score is liberal in ranking Fairness first, but very conservative in ranking the remainder roughly equally. The big gaps that liberals put between equity issues (fairness and harm), stability issues (loyalty and authority), and purity issues are absent. More interestingly, James sees a strong priority distinction between fairness and harm, which is not typical of either conservatives or liberals. That seems like the uniquely Jamesian (heh) viewpoint here.

@Mimai:

Great communicators are at least as important as great thinkers. The most revolutionary idea is worthless if it cannot be transmitted.

And the most mundane idea can transform the world if it falls into the hands of someone who is a great communicator.

Take Hitler as a (completely terrible) example. He didn’t bring anything new to the centuries old theories of anti-semitism and racial purity, he just repackaged it for the masses and hired some people who were able to merge the traditional pogrom with the economies of scale made possible by the industrial revolution. And he changed the world (for the worse).

Fun Fact: The Nazis actually had people looking at America’s Jim Crow laws for examples early on and found them too restrictive. They didn’t quite use focus groups to see how much bigotry the German people were ok with, but they were only a few steps away.

(I would say that Parler is the combination of social media with antisemitism, but it’s not like there’s a lack of antisemitism on Facebook and Twitter now)

(When someone figures out the Uber of Antisemitism, they are going to be so annoyed that the name Uber is already taken)

——

Ok, fine, Steve Jobs is a much less horrifying example. Apple never really did anything revolutionary, it just applied good design and marketing to things that were already revolutionary.

@Gustopher:

(para 1) Yep, I’m following you.

(para 2) Yep, I’m still here, this is fun.

(para 3) Whoa, that was a hard right (or left….but that’s another discussion).

(para 4) Oh good, we’re back to fun, wait NO!, we’re in even less fun territory now.

(para 5) And we keep getting more less fun.

(para 6) So very much not fun.

(para 7) Not necessarily fun but not not fun.

Sheesh, a little trigger warning would be nice.

@James Joyner:

Fair enough.

I’m not as big on prestigious credentialism as most.

I’ve taken several of the quizzes. I am a certified weirdo.

@Gustopher: @Mimai:

Well, this interaction would have made my day. But random dude who may or may not have been performing a personal passion narrative takes the cake.

Sorry.

@DrDaveT:

Yeah, I don’t consider Haidt any differently from how I think about a lot of prominent intellectuals. I like good arguments.

This all seems very reminiscent of Geert Hofstede’s six ‘dimensions of national culture’: individualism, masculinity, power distance and the rest. It would be interesting to explore the amount of overlap, but I haven’t the energy to do it on a comments thread.

@Ken_L:

Oh, don’t tease me.

My allergic reaction to Haidt, as represented here (I haven’t ready his work), is the idea that liberals care about fewer dimensions than conservatives do, and that’s somehow a problem.

I’m very surprised not to see honesty/mendacity on this list. Not only is it foundational in moral thinking (for example, see St. Augustine on how lying is the worst sin), but it’s also something that people in Western democracies do care about very strongly. Not only do we deplore when we are dishonest to each other, but we are especially irate when those in power lie to us. Again, haven’t ready his work, but I’m suspicious of any methodology that winds up excluding truth from the list. To be fair to Haidt, I’d have to look at his work to find out why.

But that’s not the core problem here. Leaving some virtues off the list is itself a meta-virtue. That’s part of the definition of tolerance, which is also oddly not on the list. There are domains of thought and behavior where the government should not adjudicate, or anyone else, for that matter. The classic example is John Stuart Mill’s drunken watchman: the problem isn’t that he likes alcohol too much. The problem is that it interferes with his duties. If he had a different occupation, then sobriety wouldn’t be an issue. Just as, to cite the classic Catholic virtues, we don’t require, as a matter of public policy, for people to be temperate or charitable. Should we pass laws requiring to give to charities, or to use the other meaning of the word “charitable,” give other people more slack? No. Should we require them, in their private lives, to be charitable? That’s highly debatable. We certainly don’t pick and choose our friends, or castigate our relatives, for failing on that measure. Both liberals and conservatives (in the classic Burkean sense of that word) see the importance of taking certain moral requirements off the table in politics for certain, and in a secular moral sense, in private realms as well.

Therefore, I see piling up a list of “moral dimensions,” and then judging the intensity of how many you care about as a measure of your moral probity, as a foolish exercise. The real problem of morality in politics is reductive, not additive. How many of these dimensions do we all agree should matter? What is the definition of a good society, as we have been debating since at least Plato’s Republic? When the Framers decided to create a new society, based on Lockean ideas of social contracts, what is the “mission statement” for the first new nation? What elements are explicitly on the list (life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness), and which are implied (tolerance)? While our political culture may have fragmented over the last few decades, to the point where we strongly disagree over which moral dimensions matter (and tolerance has taken a huge beating), the foundation of a democratic society is the consensus over which of these matter in the public sphere. You’ll never get perfect consensus over what each of those elements mean: for example, while the Framers did clearly intend religious tolerance, to some degree, in their explicit statements, many first-generation citizens of the new republic seemed hunky-dory with Protestant favoritism in the law. But they did agree enough on the list that mattered.

By the way, tolerance is based, to some degree, on things like the cardinal virtues. I’m humble enough to admit that I could be wrong. I’m compassionate enough to respect you for the sincerity of your opinions, and I will assume you want good outcomes, too. At the same time, other outcomes are dependent on tolerance. Because we are tolerant, we don’t wage ugly religious wars, or prosecute genocide against peoples who offend us. So I think it’s very hard to create a simple, flat list of “moral dimensions,” given how contingent some virtues are on others.

@Kingdaddy:

Because no one values dishonesty while everyone values all Haidt’s five dimensions to some degree. The difference is the relative degree of importance and the priority of each dimension compared to the others.

@DrDaveT:

Nice to see that we’re not always on a different page!

@Kingdaddy: I don’t have time to get into the weeds here (your post deserves thoughtful engagement). But you might find some of your concerns about omissions addressed here (among other places). https://cpb-us-e2.wpmucdn.com/sites.uci.edu/dist/1/863/files/2020/06/Graham-et-al-2013.AESP_.pdf

FYI, tolerance is included in the dictionary terms for fairness (see appendix D) https://fbaum.unc.edu/teaching/articles/JPSP-2009-Moral-Foundations.pdf

More generally, I think people vary in their expectations about what any moral foundation theory “should” do…..ie, what purpose it serves. My sense is that you and Haidt approach this with different functional expectations, hence some of your disagreement.

@Kingdaddy:

Additionally, I think you’re making the same mistake Cheryl did by assuming these moral dimensions are value judgments. They don’t measure that and it’s a mistake to suggest that scoring higher in some dimension equates in any way moral probity. Rather these dimensions are intended to explain how one’s moral values are justified, prioritized, and expressed by individuals.

Also, now that I’m remembering more of this, various people have proposed adding additional dimensions including one for honesty, as you suggested. Also, liberty, equity, and some others have been suggested.

Which all kinds of points to some of the limitations of this schema and also due to the subjective perceptions about how it might reflect on certain individuals and groups.

@Mimai: Again, I have a difficult time commenting too strongly here, given I haven’t read Haidt’s work. But if that’s what he means by “fairness,” I worry that he has overloaded the term, if it also encompasses justice. We might think of ourselves with just, without necessarily being tolerant. The law in Virginia, pre-1776, that required Catholics to either attend Protestant services or face financial penalties was certainly not tolerant. But I think the people who approved it thought that they were being just. Justice can be condescending to groups that you consider to be somehow misguided or impaired. See our many laws on how we treat the recipients of public assistance as untrustworthy.

@Andy: Thanks for your clarifications. I think I understand what Haidt tried to do. Whether Haidt himself believes that caring about a larger than average number of moral dimensions makes you more “moral” is a question I’m not qualified to answer, except by what people in this thread tell me. However, I do know that there are people who think that way. Whether you think that actually makes you more moral, or moralistic, is a separate discussion.

The core point I was trying to make is that, in the politics of democratic societies, it’s important to have a limited number of precepts that form the core of one’s political culture, tolerance being critical among them. (I think it’s important in politics anywhere, not just democracies, but it’s foundational for democracies.) Past that core of the political culture, it’s probably a good idea to introduce any additional moral dimensions very economically and carefully. There at least should be some connection between the vision of the good society in the core and the secondary values in the next ring out. For example, you might believe in this chain of logic: (1) An essential trait of public service is being just. (2) Being just requires humility in the face of unexpected consequences that may arise from your actions. (3) Therefore, you should legislate as little as possible, so you don’t keep piling up unexpected consequences from government mandates. Whether you believe in that libertarian outlook or not, at least there are connections between a core principle, justice, and a secondary principle, humility. Many times, such as in outrage at politicians who are philanderers, there is no clear connection, other than a simplistic thesis about how personally corrupt people cannot help but pursue corrupt policies. The speed with which the Christian right abandoned that position a few years ago speak not just to probable insincerity, but the fact that there wasn’t even much of a theory of good governance there in the first place, beyond, “People in power whom I deem to be morally reprehensible make me feel uncomfortable.”

@Kingdaddy:

He’s not trying to determine morality in general or adjudicate who is and who isn’t moral, or judging what makes a person more “moral” or less. He’s trying to explain the variation in how humans think about what is moral in a way that doesn’t rely on the one-dimensional binary construct of moral vs immoral.

These “moral” dimensions are intended to be explanatory and cross-cultural – ie. not limited to the peculiarities of domestic US politics and culture. Variations of the test James took have been done in other countries and the same pattern emerges everywhere as it does here in the states.

I can’t really explain it further without going back and re-reading stuff, but if you want the 40,000-foot view, he’s given some Ted Talks with the basics.

@Andy: This distinction is important, and I’m glad you keep hammering on it…….discussions of moral frameworks typically elicits such misunderstanding.

As a completely different aside, you mentioned being an intelligence analyst of some sorts? Did you rub shoulders with any of the superforecasting stuff that was funded by IARPA?

@Kingdaddy:

It’s a communication problem, not a moral problem. Again, as @Andy notes, Haidt isn’t scoring people on how moral they are — he’s characterizing people by how they determine what is more/less moral. The fact that you and I agree that nobody should be giving much weight to “chastity” in making public policy decisions* doesn’t change the fact that there are a lot of people out there who do, and who think us immoral for not caring enough about that dimension. You can’t understand those people, or have a useful conversation with them, unless you realize that. Even then, you might not be able to reach any kind of consensus — but you might be able to reach an acceptable compromise. Understanding why you (and they) need to compromise is an essential step in the process.

*I figured out a long time ago that strong anti-abortion positions are almost entirely driven by concerns about chastity, with the fairness-based “right to life” argument as a red herring.

@Mimai:

I read some of it, but was never involved or knew anyone who was. I worked in the Defense Department, so my focus was primarily military threat analysis.

@Kingdaddy:

I haven’t read the book form of Haidt’s argument but don’t glean that from the article-length versions. Rather, he’s arguing that conservatives (and he drew this insight from very early fieldwork in India not the US political scene, so he really means “traditionalists”) make moral judgments on a wider number of instincts than do liberals. He argues that liberals have these same instincts but don’t view them as reasonable bases for making moral judgments.

I agree and gather Haidt does, too. His point, though, is that you’re not going to persuade conservatives/traditionalists that their moral judgments based on loyalty or purity are wrong on the basis of appeals to fairness or harm.

@DrDaveT:

I’m not sure I necessarily rank them in the order that the test shows but I’m a rationalist with some strongly conservative instincts. So, for example, I’m not sure my visceral instints on trans issues are much different from, say, Rod Dreher’s. But my intellectual impulse is that we should make public policy on the basis of care, fairness, and liberty with process and humility as the primary nods to sanctity and authority.