James Brady, Former Reagan Press Secretary, Dies At 73

James Brady, who served as President Ronald Reagan’s Press Secretary and became the symbol of the gun control movement after being shot during the assassination attempt on the President in March 1981, has died at the age of 73:

James S. Brady, the often-irreverent press secretary to President Ronald Reagan who was shot in the head during an assassination attempt on his boss in 1981 and who became an enduring symbol of the fight against unfettered access to guns in American society, died Aug. 4 at age 73.

The Associated Press reported that his death was announced by his family. No other details were immediately available.

Mr. Brady remained an influential presence in the gun-control debate decades after the shooting that left him partially paralyzed. He and his wife, Sarah, often described as the “first family” of gun control, battled six years to pass legislation that in 1993 ushered in background checks for handguns bought from federally licensed dealers.

Mr. Brady was a veteran Republican aide and a popular figure among Washington journalists. He was equipped with a rapier wit and a buoyant charm that tended to defuse controversy, even before he began working for the White House in January 1981.

Incoming first lady Nancy Reagan had reportedly urged her husband to appoint a press secretary who was young and handsome enough to represent the White House on television.

Nicknamed “The Bear” for his burly physique, Mr. Brady was also balding and nearing 40. At the next press briefing, he quipped to the gathered press corps, “I come before you today as not just another pretty face, but out of sheer talent.”

The assassination attempt, 69 days into the Reagan presidency, redefined Mr. Brady from a garrulous footnote in American politics into an impassioned and often-impatient voice for gun-control legislation.

On March 30, 1981, Mr. Brady had originally asked one of his aides to go with the president on a routine assignment to address a gathering of the AFL-CIO at the Hilton Hotel in Washington. Mr. Brady changed his mind at the last minute and joined Reagan.

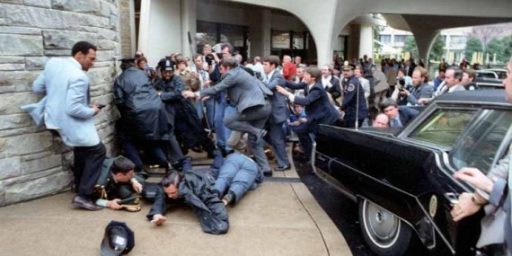

After speaking to the union delegates, Reagan and his party made their way out of the hotel and were walking to the presidential limousine when they were fired upon about 2:30 p.m. The shooter was John W. Hinckley Jr., a young man who said he hoped the assassination would impress the actress Jodie Foster.

Outside the Hilton, bystanders, police and Secret Service agents wrestled Hinckley to the ground and arrested him. He got off six bullets from the .22 caliber Rohm RG-14 revolver, which he had bought at a pawn shop in Dallas for $29.

Mr. Brady was the first person hit and was struck above the left eye. Reagan had been hit by a bullet that bounced off the limousine. Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy and Washington police officer Thomas Delahanty were also injured in the attack. Brady, Reagan and McCarthy were taken to George Washington University Hospital. Delahanty was taken to the Washington Hospital Center, which is now known as MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

The bullet that entered Mr. Brady’s head shattered into more than two dozen fragments, with several penetrating his brain.

His condition was so dire that Secret Service agents at the hospital reported erroneously to their superiors that the press secretary had died. CBS, NBC and ABC reported the news — later retracted — while delivering updates on the president.

Mr. Brady was not dead but he was close.

Neurosurgeon Arthur I. Kobrine later recalled telling the president’s personal physician about Mr. Brady: “It’s a terrible injury. I don’t think he has a chance. I don’t think he’s going to make it, but I think we should try.”

Mr. Brady came through the surgery well but the road ahead was punctuated by dramatic ups and downs. In the next several months, he underwent two surgeries to halt leaks of spinal fluid from his cranial cavity, another surgery for a pulmonary embolism, and had epileptic seizures, pneumonia and persistent fevers.

Officially, Brady retained the title of Press Secretary throughout the Reagan Administration, although his duties were minimal going forward. Today, the press briefing room at the White House is named after him. Over the next thirty years, Brady, along with his wife, would become a leading figure in the gun control movement:

In public appearances, congressional testimony and through the news media, Sarah Brady became the public face of the gun-control movement in America. She used her husband’s story to rally support for legislation.

She joined what was then a little-known lobbying group, the National Council to Control Handguns, which was later called Handgun Control Inc. and is now the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

Mr. Brady joined his wife in the gun-control efforts, but his physical limitations made it difficult for him to play more than a supporting role for his wife’s endeavors.

The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act was first introduced in Congress in 1987. The key provision of the bill imposed a background check — as well as a waiting period to buy a handgun from a federally licensed dealer. The background checks were designed to uncover those who had been barred from buying guns, including felons and the mentally ill.

During one of the many skirmishes that took place over the years before the Brady bill’s passage, Mr. Brady testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee and said that members of Congress who declined to support the measure in previous votes were “gutless” for their “pandering” to the National Rifle Association.

The influential gun lobby opposed the measure on several grounds, among them that any waiting period would inconvenience legitimate gun buyers.

In his testimony, Mr. Brady noted poignantly, “I need help getting out of bed, help taking a shower, and help getting dressed, and — damn it — I need help going to the bathroom. . . . I guess I’m paying for their convenience.”

Nearly 10 years to the day after he was nearly killed by Hinckley, Reagan himself joined the fray, announcing his support for the Brady bill in an op-ed piece in the New York Times. President Bill Clinton signed the bill into law in 1993.

As activists, the Bradys were gradually joined by a growing roster of political voices such as Rep. Carolyn McCarthy (D-N.Y.), whose husband was killed and her son wounded in a 1993 gun massacre, and Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.), who suffered traumatic head wounds in an assassination attempt in 2011.

The Brady bill would be cited time and again as a symbol of the importance of gun-control laws, but there was debate over the measure’s actual effect.

In 2000, a study conducted by public policy professors Philip J. Cook of Duke University and Jens Ludwig of Georgetown University found that the Brady bill — at least in its initial form — had probably not been a factor in reducing gun-related homicides nationwide.

Those of us who were alive during for the events of March 31, 1981 well remember the erroneous reports of Brady’s death. As it turned out, he had something more to give to his country.