Afghanistan Is Not Like Iraq, Even If The Same General Is In Charge

The odds that David Petraeus will be able to pull off a miracle in Afghanistan like he did in Iraq are very slim.

Thomas Ricks, a Washington Post military reporter who wrote Fiasco: The American Military Adventure In Iraq is out this morning with a piece explaining why General David Petraeus’s success in Iraq does not provide any guideline for how his strategy and tactics might fare in Afghanistan:

What allowed Petraeus to succeed in Iraq was not the troop surge itself; after all, a city as big and sprawling as Baghdad, with 5 million people living in two- and three-story homes, can swallow 30,000 troops without a burp. Nor was it his development of a counterinsurgency doctrine for the Army. The key tenets — such as focusing on protecting the population, while still going after the diehard insurgents, and splitting rather than uniting the enemy — were familiar stuff to anyone who had read the books. It seemed novel only in the context of Iraq, where for many years the American commanders had terrified families by knocking down doors in the middle of the night, treating locals not as the prize to be won but as the playing field on which they confronted the insurgents.

Rather, Petraeus’s critical contribution in Iraq was one of leadership: He got everyone on the same page. Until he arrived, there often seemed to be dozens of wars going on, with every brigade commander trying to figure out the strategic goals of a campaign. Before Petraeus arrived, the top priority for U.S. forces was getting out. After he took over, the No. 1 task for U.S. troops, explicitly listed in the mission statement he issued, was to protect the Iraqi people.

Of course, establishing cohesion in the nation’s effort in Iraq took a lot more than issuing statements. In spring 2007, I watched Petraeus work hard to establish a consensus about what the goals should be and how to achieve them. “There are three enormous tasks that strategic leaders have to get right,” he told me one day in Baghdad. “The first is to get the big ideas right. The second is to communicate the big ideas throughout the organization. The third is proper execution of the big ideas.” An astute bureaucratic operator, he used a variety of studies and panels convened in his Baghdad headquarters to pull together the big ideas of how to deal with the insurgency, how to better protect the Iraqi people. These had the useful side effect of getting buy-in from civilian American officials in Iraq.

Just as important, he worked tirelessly with his military subordinates, going out and talking not just to the division commanders below him, but to their brigade commanders and even to the battalion commanders an echelon below them. He issued letters to the troops explaining the new approach of living among the people and protecting them with small, vulnerable outposts. He walked the streets and talked to Iraqis. He also hired a leading counterinsurgency expert, David Kilcullen, an Australian infantry officer turned anthropologist, to coach American commanders, making sure that they not only talked counterinsurgency but that they also learned how to practice it. In a series of interviews I conducted with Petraeus in 2007 and 2008, one of his favorite words to use was “relentless.” It is the best one-word summary of his approach.

When he arrives in Kabul, however, Ricks notes that Petraeus will find himself in a much less unified position than he had in Baghdad:

In Kabul, alas, Petraeus will find no such useful ally in the American ambassador. Instead, the top U.S. diplomat there is Karl W. Eikenberry, who relentlessly opposed McChrystal’s initiatives. Unlike Crocker, Eikenberry has no strong base in the State Department and is not steeped in the history and culture of the region. Rather, he is a retired general who in fighting with McChrystal over the past year used many of the same arguments that another American commander, John Abizaid, had used in opposing Petraeus’s approach to Iraq. That is no coincidence — Abizaid and Eikenberry have been close friends since they were West Point roommates in the class of 1973.

On top of that, Petraeus will have to deal with Richard C. Holbrooke, who seems to have achieved little as a special presidential envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan. And the general will face a host government even more troublesome than what he dealt with in Baghdad. Indeed, the two biggest problems the United States faces in Afghanistan are the Karzai government and the Pakistani government — and neither of those really can be addressed by military operations.

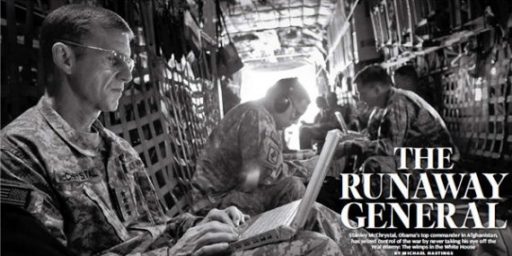

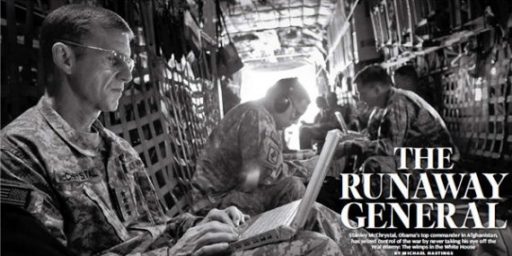

McChrystal was dismissed because of the magazine article that laid before the world the sniping and backbiting between U.S. military and civilian officials in the Afghan war. That is not going to end just because Petraeus goes to Kabul, or even because the president has said he doesn’t like it. It might end only when one person is put in charge of the overall American presence in Afghanistan, with the power to hire and fire. Obama has not taken that step, so it is likely that the same nettlesome quarrels that exasperated McChrystal also will fatigue his successor.

What this seems to obviously argue for, of course, is a re-working of the civilian leadership on the American team in Afghanistan. Obama has shown no signs that he’d be willing to do that and his reliance on Holbrooke in particular as his “eyes and ears” on the ground is quite apparent. Until that happens, the personality conflicts that came to a boil in the McChrystal interview will, most likely, continue to exist.

Ricks misses the point, however, by just concentrating on the personality conflicts on the American team. In addition to disunity among his civilian counterparts, after all, Petraeus will also encounter in Afghanistan a nation that is far less unified than Iraq ever was, and a civilian government that has far less credibility on the ground. That fact alone argues strongly that a strategy that has, as it’s base, the idea of unifying the country, will be difficult to pull off successfully.

Petraeus pulled George W. Bush’s feet out of the fire in Iraq, but it’s highly doubtful that he’ll be able to accomplish the same thing for Barack Obama.

A substantial problem is that by some accounts Amb. Eikenberry is opposed to the strategy the White House has supported for Afghanistan. Replacing a general who supports the strategy while retaining an ambassador who opposes it doesn’t sound like a formula for strategic success to me.

Eikenberry needs to go for sure. Probably Holbrooke, though I am not sure he plays as important a role. Petraeus may be helped by his recent stint at CENTCOM and getting to know Paksitani leaders better. Still, your points remain. I would also add in the problems of dealing with NATO troops as we are not the sole military presence.

One huge advantage Petraeus will have at the start are the ROEs. By all accounts, people are unhappy with McCHrystals very tight ROEs. Petraeus can change that and, possibly, get the troops all on one page and energized again. It just wont matter though unless he can figure out how to get Afghans, especially the Pashtuns, to want to oppose the Taliban in some meaningful manner.

Steve

And then we have to deal with Biden. The model of the Vice President who is as actively pushing his personal policy views as the current and previous Vice Presidents have is a continuing problem.

PD- How so? I think we should choose our VP candidates largely based upon foreign policy knowledge/experience. That was one of the reasons I voted for Bush. However, I didnt realize that Cheney would take over foreign policy completely. That is a problem, but just having someone who lobbies for a position should be workable.

Steve

Interesting, I voted for Al Gore largely based upon foreign policy knowledge/experience.

The VP is not accountable to the President. Any restraint in advancing his points of view must depend upon his own personality. Biden is clearly not capable of a large degree of self restraint and part of the McChrystal drama has its seeds in Biden seeing his duty not to the President, but to advancing what he sees as the better policy. Biden appears to see the setback on the Kandahar offensive as a vindication of his policy views. And it appears that McChrystal probably believed that in order to do his job he needed to be press accessible.

I don’t ascribe ill motive to Biden or Cheney, but I don’t believe the VP office was intended to function that way, and when it is used that way, the VP becomes a key actor in conflicts that the President can’t simply address as he can with those who serve at his pleasure.

Telegraph is reporting that Petraeus is going to review the ROE.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/barackobama/7852684/Gen-David-Petraeus-to-review-courageous-restraint.html

Afghanistan people have battled for thousand year. American will not win the war