An Observation or Two on SCOTUS

Well, more than two...

I took the above photo on a trip to DC in November of 2022. Rather obviously the protest was in the wake of the Dobbs decision. While long-time readers may recall that I tend to be slow to use terms like “illegitimate” and further try to be quite precise in my application of the term (for example, a post from 2017: Will Donald Trump be a “Legitimate” President?), I couldn’t help but think of this image as I was working on this post, which is not so much about Dobbs as it is about my growing concern about what I perceive as the Supreme Court’s lack of seriousness. And, yes, while I agree that the problem is predominantly the conservative majority, I was underwhelmed by the liberal minority’s approach to the 14th Amendment ruling.

Now, to be clear, the current Court was appointed and confirmed via legitimate means (but, yes, the whole Scalia replacement business, as well as the rush to replace Ginsburg was definitely problematic), so I am not claiming otherwise. Still, the Court is clearly behaving in ways that the general public does not appreciate, which does erode its legitimacy (given that legitimacy is both a legal and a public perception issue).

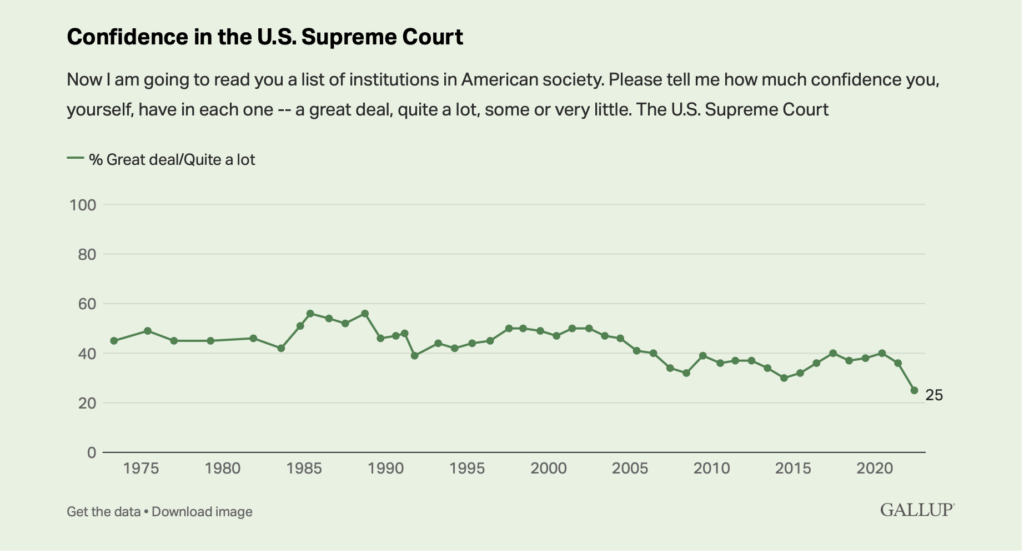

To wit via Gallup, Confidence in U.S. Supreme Court Sinks to Historic Low.

There is little doubt in my mind that the flaws in the supposedly democratic inputs into the appointment process (the Electoral College plus the Senate) coupled with the arbitrary timing of vacancies have contributed to the public sentiments reflected above (plus the current polarization and discontent in our politics). While the general public may not think much about it, or even fully understand the dynamic, the reality is that the Court has very much been shaped by minority political sentiment in the country, and so it is not surprising that the majority of citizens object to the Court’s behavior and rulings.

A key frustration that I have is that the Court pretends (and I use that word because I believe it is deliberate) like it is above partisan politics, and is simply applying legal theory to interpret texts, as wise sages do. They pretend like they are above it all and that their rulings just provide guidance for the rest of the government to follow. In the abstract, there is something to that claim. But as a practical matter, this is simply not true.

For example, it is a dodge to pretend like the legislature will fix a given issue. On the one hand, I fully understand why that not only sounds like a legitimate position but that that is a preferable way to operate. On the other, if it is obvious that the legislature is not going to address, let alone fix, the given issue then that fact has to be taken into account by the Court when it makes its decisions.

Put another way: if SCOTUS knows (and yes, they know) that providing a specific interpretation of a law will render that law moot and that Congress will not be able to address the mooting, then they are effectively legislating themselves. And, again, they know this. This is especially true when they could either defer to the existing law or make a narrow ruling. Every choice they make is just that, a choice. It is not some magical result that following rules of interpretation requires.

If my car is not working and the best solution is a part that will not be available until some unknown time in the future or there is some less perfect solution that will allow my car to function again, guess which option I will prefer?

In my own professional life, I know that there is often a solution to a problem that requires everything else in the world to operate optimally, and there is a solution that has to take into consideration that the world does not, in fact, operate optimally. As such, the sub-optimal route has to be pursued because pretending like the optimal one will eventually just happen means that there will be no solution to the problem and that other problems will proliferate as a result.

To govern otherwise is folly. And make no mistake, SCOTUS governs when it makes decisions. Further, it is part of the overall policy-making environment (see, e.g., the effects of the Dobbs decision if one needs a recent example).

To be clear: I would prefer a world in which there is an ongoing dialog between the legislature and the courts in a way that would refine and fine-tune the laws and public policy. But we have never really had such a system. Or, perhaps it would be more accurate to state that such interchanges are more rare than they are routine.

I especially find it problematic that the Court will pretend like it is just asking questions, or seeking clarification, while fully well knowing that what they are doing is overturning a law (and perhaps a policy regime) that will not be fixed by quick legislative action. I fear we are headed in such a direction when it comes to the entire basis of the US regulatory state (see SCOTUSblog, Supreme Court likely to discard Chevron).

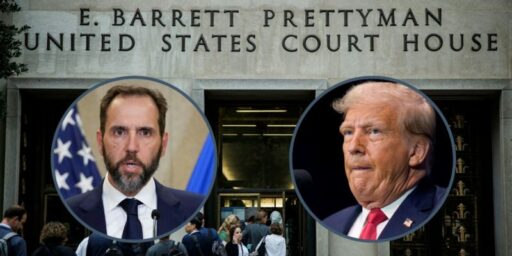

I find this general problem to be inherent in their approach to the immunity claims made by Donald Trump (as well as to their ruling on section 3 of the 14th Amendment, see SCOTUS Leaves Trump on Colorado Ballot). They (and I mean mainly here the conservative majority, although as noted above, not just) can pretend like they are dealing with abstract principles and that they are above politics, but the reality is they understand, like they do with rulings on legislation, that there will be no immediate fix to the problems they create.

The lofty sentiments that they use to obfuscate their political preferences are naught but a smoke screen and belie not only partisanship but also their unwillingness to be responsible in a time of potential national crisis.

It is the lack of responsibility that frustrates me the most. An institution with the vast powers of the Supreme Court requires responsibility and seriousness if it is to operate anywhere near justly.

We know that they can try and be narrow as to their rulings. In Bush v. Gore, they played the game of “this ruling is only about now and not the future.” And yet with Trump’s immunity claims, they have decided to play the game of “we have to worry about the Big Picture and Vague Future Possibilities.” Of course, it is no coincidence that the game chosen in each case just so happens to fit the personal political preferences of the majority.

These are ongoing thoughts that I have had, but they were crystallized in recent days. And I agree with the following sentiments from Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern in Slate (The Last Thing This Supreme Court Could Do to Shock Us).

For three long years, Supreme Court watchers mollified themselves (and others) with vague promises that when the rubber hit the road, even the ultraconservative Federalist Society justices of the Roberts court would put democracy before party whenever they were finally confronted with the legal effort to hold Donald Trump accountable for Jan. 6. There were promising signs: They had, after all, refused to wade into the Trumpian efforts to set aside the election results in 2020. They had, after all, hewed to a kind of sanity in batting away Trumpist claims about presidential records (with the lone exception of Clarence Thomas, too long marinated in the Ginni-scented Kool-Aid to be capable of surprising us, but he was just one vote). We promised ourselves that there would be cool heads and grand bargains and that even though the court might sometimes help Trump in small ways, it would privilege the country in the end. We kept thinking that at least for Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch and Chief Justice John Roberts, the voice of reasoned never-Trumpers might still penetrate the Fox News fog. We told ourselves that at least six justices, and maybe even seven, of the most MAGA-friendly court in history would still want to ensure that this November’s elections would not be the last in history. Political hacks they may be, but they were not lawless ones.

On Thursday, during oral arguments in Trump v. United States, the Republican-appointed justices shattered those illusions.

I had hoped (and I use that word very deliberately) that the Court would be more serious than it has proven to be. I had hoped that it would have been willing to act with more alacrity than it has. Regardless of one’s views of Trump or of January 6th, it seems rather obvious that the country would be better served to have as much legal closure on those topics as possible. At a bare minimum, the extraordinary nature of the times should have resulted in expeditiousness on the part of all actors. Or, more precisely, the various courts involved should see the importance of the trial and not treat it like it is just like every other trial. The only person who wants this all slowed down is Trump, and as Ronald Brownstein in The Atlantic noted right after oral arguments, Trump Is Getting What He Wants.

At today’s hearing on Donald Trump’s claim of absolute immunity from criminal prosecution, the Republican-appointed Supreme Court majority appeared poised to give him what he most desires in the case: further delays that virtually preclude the chance that he will face a jury in his election-subversion case before the November election.

[…]

After today’s hearing, the hope that a trial could proceed expeditiously now “seems fruitless, and the question is whether the Court will issue an opinion that will provide expansive, albeit not unlimited, immunity, which would be a giant step toward rejecting the idea the president is not a king, a fundamentally anti-constitutional principle,” the former federal prosecutor Harry Litman, the host of the podcast Talking Feds, told me.

[…]

“Even if it’s pellucidly clear that the standard [for immunity] wouldn’t apply to Trump, I do think he likely would get another trip back up and down the federal courts, very likely dooming the prospect of a trial in 2024,” Litman said.

To be clear: Trump deserves due process like everyone else and, moreover, I understand that that means the right to employ favorable tactics, including trying to delay. But, the federal court system, including SCOTUS, is not required to help him do so. Moreover, given that part of the reason for Trump’s desire to delay is the election and the potentiality of being able to either end the cases by ordering DoJ to do so, self-pardoning, or some other extraordinary action should be compelling the courts to be far more expeditious than they are clearly willing to be.

These are not typical charges.

He is not a typical defendant.

The timeline and constraints thereof are unique in American jurisprudence.

The consequences of handling this all incorrectly are well beyond whatever effect they will have on Donald J. Trump, defendant.

And, I suppose, this is the point (or collective points) of this somewhat discursive post: it is a dereliction of duty for the Supreme Court in particular to have allowed this immunity issue to be used as a delaying tactic in this way (they had various options that could have sped this process up). Likewise, it is unconscionable, in my view, that the conservative majority on the Court was willing, and is likely to continue to be willing, to ignore the core reality that the question is not “one for the ages” (as Gorsuch put it) in some abstract sense concerning hypothetical presidents in the far future.

No, it is “one for the ages” in the sense that we are dealing right here, right now with a former president, and current presumptive nominee of his party, who helped foment an insurrection against the United States, and engaged in a variety of other actions (such as blatantly asking the Georgia Secretary of State to find more votes) all in furtherance of subverting election results.

To quote the McConnell speech that I noted yesterday:

A mob was assaulting the Capitol in his name. These criminals were carrying his banners, hanging his flags, and screaming their loyalty to him.

It was obvious that only President Trump could end this.

Former aides publicly begged him to do so. Loyal allies frantically called the administration.

But the president did not act swiftly. He did not do his job. He didn’t take steps so federal law could be faithfully executed, and order restored.

Instead, according to public reports, he watched television happily as the chaos unfolded. He kept pressing his scheme to overturn the election!

Even after it was clear to any reasonable observer that Vice President Pence was in danger, even as the mob carrying Trump banners was beating cops and breaching perimeters, the president sent a further tweet attacking his vice president.

That the man being described above has not been shunned from American politics is stunning. And yes, the Republican Party (with McConnell very much included because of his cowardice regarding impeachment, and his craven partisan blinders since that time) deserves condemnation for not exiling Trump to Mar-a-Lago.

I can’t but help view Justices Alito, Thomas, Kavanaugh, and Gorsuch (and likely Roberts) as being no different than McConnell, McCarthy, and a whole slew of their co-partisans. They are clearly making politically expedient choices that favor their partisan fellow travelers rather than looking out for the good of the country.

As Adam Sewer noted in The Atlantic (The Trumpification of the Supreme Court):

Trump’s legal argument is a path to dictatorship. That is not an exaggeration: His legal theory is that presidents are entitled to absolute immunity for official acts. Under this theory, a sitting president could violate the law with impunity, whether that is serving unlimited terms or assassinating any potential political opponents, unless the Senate impeaches and convicts the president. Yet a legislature would be strongly disinclined to impeach, much less convict, a president who could murder all of them with total immunity because he did so as an official act. The same scenario applies to the Supreme Court, which would probably not rule against a chief executive who could assassinate them and get away with it.

[…]

The Supreme Court, however, does not need to accept Trump’s absurdly broad claim of immunity for him to prevail in his broader legal battle. Such a ruling might damage the image of the Court, which has already been battered by a parade of hard-right ideological rulings. But if Trump can prevail in November, delay is as good as immunity. The former president’s best chance at defeating the federal criminal charges against him is to win the election and then order the Justice Department to dump the cases. The Court could superficially rule against Trump’s immunity claim, but stall things enough to give him that more fundamental victory.

Indeed.

Trump has the conservative justices arguing that you cannot prosecute a former president for trying to overthrow the country, because then they might try to overthrow the country, something Trump already attempted and is demanding immunity for doing. The incentive for an incumbent to execute a coup is simply much greater if the Supreme Court decides that the incumbent cannot be held accountable if he fails. And not just a coup, but any kind of brazen criminal behavior.

[…]

No previous president has sought to overthrow the Constitution by staying in power after losing an election. Trump is the only one, which is why these questions are being raised now. Pretending that these matters concern the powers of the presidency more broadly is merely the path the justices sympathetic to Trump have chosen to take in order to rationalize protecting the man they would prefer to be the next president. What the justices—and other Republican loyalists—are loath to acknowledge is that Trump is not being uniquely persecuted; he is uniquely criminal.

And this is the core of it. And since I refuse to believe that the conservatives on the Court can’t understand this (I hear tell that they have all had pretty good educations), I can only see them as willingly complicit in what is unfolding before us.

At a bare minimum, they have already chosen not to use their authority to speed this process up in a variety of ways and we may all yet suffer grave consequences as a result.

While recognizing that the ruling has not been issued, I will say that this Court is working hard to classify itself as being in a category of infamy that the Taney Court that issued the Dred Scott ruling currently occupies.

Nice piece. I lost faith in SCOTUS a long time ago. It has long been clear that the judges are merely partisans wearing robes, there to enact their political preferences as law. As such, I am not happy with the current make up of the court. However, that make up is at least partially due to GOPO bad conduct by McConnell. By reasonable standards there should be at least one more liberal judge. Then look at the ages. The trend is to get judges as young as possible because they are going to be on the court forever. We arent choosing people with the legal and life experiences to give us the best quality decisions, we are clearly choosing people who will make the decisions we want for as long as possible.

But, it goes well beyond that. SCOTUS is severely lacking in ethics and integrity compared with other courts in the US. Multiple member receiving lots fo money and gifts, being married to political activists, not recusing themselves from cases involving people who gave them gifts or said spouses being involved in cases they rule on. They cant even make some minimal effort to appear as though they might not be influenced inappropriately in their decisions.

SCOTUS needs major reforms, largely in limiting length served. Make it 4 or 6 years like other politicians. Unfortunately, SCOTUS largely has free rein since Congress is mostly useless so that wont happen. SCOTUS also needs some ethics rules with some bite, but as long as they get to make their own rules that wont happen.

Steve

Good summary of the situation. The Court majority has been bought and paid for by the Koch/Leo Federalist $ociety. They hang their hats on “Originalism” as the only “legitimate” mode of interpretation, but when it doesn’t produce what they want they abandon it in favor of consequentialist arguments to keep Trump on the CO ballot and look to be doing the same with Trump’s facially absurd immunity claims. They are, and should be viewed as, illegitimate.

This is greatly aided by the filibuster.

I’m not saying that if we got rid of the filibuster that the legislature would provide quick legislative fixes, but simply that it serves as a ratcheting effect on this deregulation by court fiat.

(Killing the filibuster would also mean we get a lot of crazy shit passed, until the electorate realized that maybe electing lunatics is a bad thing. For ages, they’ve been able to elect lunatics with very few consequences.)

You didn’t even bring up the major question doctrine which seems applicable only when they do not like Democratic policies and even trumps originalism and strict statutory construction, both ostentatiously conservative dogmas until they aren’t. And apart from civil rights and electoral laws, the current Supreme Court jurisprudence on armaments is a literally joke. Not a single opinion is based on anything resembling the historical antecedent including the 2d amendment itself. A well know fact is that even in 1789, gun regulation including outright banning was common. The current interpretation is based only on a radical movement the last forty years. It would be funny if it was not so egregiously wrong.

I suggest there’s a non-negligible chance at least some justices are motivated by craven cowardice in the Trump immunity case, trying to delay a decision in the hope Trump wins in November and they can dismiss the whole thing as moot after the incoming Attorney General ends all the trials.

While agreeing with much of what you say, I can’t help but point out that due process (as you define it) is not something that “everyone else” can have. It is reserved to the wealthy, who can afford the legal firepower to pursue it. That’s an unsavory fact, but true nonetheless. Harvey Weinstein has rubbed all of our noses in that fact just recently.

If Trump were President again, the Supreme Court is yet another institution to be ignored, degraded, humiliated, corrupted, toppled. It’s a testament to the hubris of the justices that they think it won’t happen to them.

Interesting piece. I think you view the Court in far too utilitarian terms and place obligations on it that you wish it had or think it ought to have that it doesn’t have. For instances:

Fundamentally, the mistake here is the idea that the Court must make some kind of judgment on the likelihood of the legislature fixing a given issue and then must take that judgment into account in its decisions. The must do neither of those things and I would argue they should not do either of those things. There is certainly no requirement for that.

What a legislature may or may not do in the future is not knowable, especially as you expand the time horizon. Yes, it may be obvious that this Congress is not going to pass 14th amendment legislation, but it’s not obvious that no future Congress will.

If everything they legislating, then I guess that goes a long way to explain why so many people want to to essentially be legislators and act to create law when Congress hasn’t or won’t and why so many think they are just politicians in robes. If that’s what people think, then the court will never have any legitimacy.

and

And this is where I think your view of the court is incorrect. The fact that courts’ decisions affect the real world does not mean they are governing. The view that courts are obligated to “fix” the car, even imperfectly, and are especially obligated to act to fix the care in the absence of action by other branches of government, fundamentally, IMO, misunderstands the role of the courts in our system.

As a general point continuing from a previous thread on Executive and administrative power, I would point out again the dissonance I see in the various incongruent arguments about democracy. On the one hand, our system is supposedly not very Democratic, especially when it comes to the selection of the President and the Senate, which select the SCOTUS, which is not Democratic at all. On the other hand, I see calls for the President and administrative state under that office, as well as SCOTUS and the courts generally, to exercise more power and more active authority to do everything from implementing pet policies to grandiose ideas about saving democracy.

Well, I’m sorry, but you can’t have it both ways. You don’t get more and better democracy by encouraging, insisting, or demanding that the least democratic institutions exercise more power because the legislature is unable or unwilling to do what you think is necessary. That road leads down a very different path than more democracy.

@Andy: But Andy, Congress did pass 14th amendment legislation by overwhelming majorities and signed by the president but Roberts declared that was racism was over (yes he did) and held the provision unconstitutional despite the amendment explicitly granting the right to Congress to enact legislation on the matter. Basically the court ruled that the constitution was unconstitutional, so I disagree with your deferential formulation.

@Andy:

The Court makes binding, authoritative deployments of power as part of the broader constitutional and governmental framework.

By definition, they are governing.

@Andy:

I understand the critique, and will own it, to a degree.

I don’t have time to elaborate further, save to note that the Court could simply choose not to act, or could act narrowly.

I think you are letting them off the hook by acting like they don’t have the intelligence nor the agency to understand the consequences of their actions.

@Andy: I agree almost entirely with this analysis. In short, having conceded that the legislative branch will under-function in its proper legislative role, Dr. Taylor is asking the Court to over-function to fill in for the legislature. Asking this is to ask the Court to implement what Congress “meant to do” or “should have done.” I don’t think that will lead where you want it to go.

@Joe: That really isn’t what I am saying.

@Joe:

My view is that if the legislative branch is under-functioning, then the answer isn’t to encourage a de facto transfer of authority to the least democratic branch in the name of expediency (or the administrative state under the Executive branch). Unlike Congress and the President, who must answer to the people, the Court is designed to have independence but limited authority. If you seek to expand that authority by allowing or encouraging it to do what you think Congress meant or should have done, then you have no way to claw that power back in the future.

And how, exactly, does that improve the legislature?

Furthermore, this would only increase the politicization of the Court, as people will see the path to getting what they want lies there (more than they already do), not via the legislature. The result will only further weaken the legislature and raise the stakes for appointments higher than they already are.

No, I think the result will lead exactly where I’m suggesting it will go.

@Andy: Andy I suggest your discussion of a hypothetical future is misplaced. The developments you describe have largely occurred already. Disaffected interest groups from both sides of politics have been turning to the courts to make new law since at least Roe v Wade, and it’s hard to imagine them being any more politicised than they already are short of a complete overturn of the constitutional order.

@Andy:

What particular limit did you have in mind? They are the sole arbiters of what is constitutional, and the sole arbiters of what the legislature actually meant. They don’t have a police force of their own, but apart from that…

@Andy:

When it comes to the way the administrative state works, the legislative intent it pretty clear. The entire apparatus was created by Congress.

If the Court overturns that, they will be making some very hefty governing decisions because they will knowingly upend decades of operations (a not especially conservative thing to do).

And they will do so knowing full well that Congress will not be able to fix the chaos.

That is a choice.

@DrDaveT:

I’m specifically arguing against the idea that the Court ought to expand on that to “fill in” for the legislature. Once they start doing that, what mechanisms are available to stop them?

@Ken_L:

On the contrary, things can get much worse.

@Steven L. Taylor:

On the contrary, the legislative intent is often not clear. Or the Executive increasingly does things that most people agree are unconstitutional and then dares the courts to stop them. Super democratic!

A government in which all or most of the action occurs in a dance between Executive action taken by fiat under dubious rationales that are either sanctioned or not by the courts is highly problematic, in my view. I don’t see how people can advocate for that as an expedient measure to get the policy or outcomes they want while, at the same time, complaining about democracy.

@Andy:

I am speaking here of the general intent to creating the regulatory state. By definition if a system has been in place for 40+ years, and if the Congress continues to support and augment that system, the basic intent is clear.

It is quite clear that Congress endorses the rule-making we see in entities like the EPA and FDA.

I am mostly arguing for judicial restraint–and to be clear I am talking about the Chevron case, as noted in the OP.

And I am pointing out that the Court often acts like they are just punting to Congress, when they know full well that they are not but know that they are substituting their preferences for what Congress established.

In terms of the Trump cases, I am asking the Court to take more seriously the situation and to act with some expediency.

I will violate a rule of the internet, and note that my positions are contradictory to a point.

However, I would note that when I outline the actual solutions to these problems, I am told that reform is a pipe dream. Here I am engaging in a bit more practical politics and I am being told I am violating my pipe dream.

I will, no doubt, return to this topic.

@Andy:

Serious question: what policy outcome do you feel I am advocating for?

I took the post to less be demanding that the Court step into the role of the legislature and more pointing out how transparently partisan the Court has become, and how little any principles it might espouse carry weight.

I can recall a day when decrying “activist” judges who are “legislating from the bench” was a standard talking point among conservatives. And that’s exactly what this Court is doing.

I no longer give a fig of respect for any “principles” espoused by the majority of this court. If one’s principles do not hold up to the pressure of expediency, they were never your principles. You were just fooling yourself, and maybe others along with you.

I do hold out the hope that the demonstration that was the oral arguments for the Trump immunity appeal was just that: A demonstration for the faithful, knowing that the ruling they must make is going to be unpopular. They just want all the Real Americans to know how reluctant they are to decide against Trump.

That’s my hope. I make no claim about likelihood.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I agree with the general intent of the regulatory state, but what has happened in recent decades in response to political division, polarization, and a lack of action by Congress is that Presidents have increasingly used the regulatory state in novel and expansive ways. The reason the Court is going to revisit the Chevron doctrine is precisely because Presidents are no longer merely using the administrative state for necessary rulemaking and implementation and perhaps bending things via rulemaking power here and there, but as a shadow legislature to make policy that Presidents are unable to do via the normal legislative process. Create programs out of whole cloth. Take a decades-long understanding of the intent of Congress and reversing the rule for it 180 purely for political and policy reasons. Such things are not what the regulatory state is supposed to be for, and the Chevron doctrine wouldn’t be at risk if recent Presidents hadn’t chosen to try to use it as shadow legislation.

If the Executive branch is making shit up via the rulemaking process, then shutting that down and punting to Congress is exactly what the court should be doing IMO.

I get that for political reasons many people want Trump trials to happen before the election. But since it took the DoJ over 2.5 years to bring charges, there was never any chance Trump’s trial would happen and be over in a year, considering to complexity of the case and all the various issues. The OJ trial was three years. Even if the Supreme Court fast-tracked it, the trial isn’t going to happen before the election. And there’s no legal reason for the SCOTUS or the courts generally to fast-track it. Election timing is not a valid reason for speeding up a process, especially if the defendant doesn’t want it.

I’m not saying your arguments here are a pipe dream. I simply think they are wrong. I think it’s bad to promote increased Executive and Judicial power and authority to offset any real or perceived weakness by the legislature.

I don’t know—but clearly, there must be something, or you wouldn’t be advocating for the Court to “govern” and fix problems that Congress won’t. That strongly implies to me that there are things you think need doing that aren’t getting done that are important enough to you to advocate for the Court expanding its role to fix what Congress is neglecting. In this post you lean heavily into Trump’s trial and the Court’s “dodge” of the 14th Amendment ruling, so I guess I’d start there. If you want to list the problems and policies, feel free, but I have no objections to whatever your ends or policy goals happen to be. My objection is the means.

I don’t care what the policy goals are, I’m opposed on principle to further expansion of Executive and Judicial power at the expense of the Legislative branch, and if that means some things don’t get done until Congress gets it act together or until one party or another gets enough control to actually pass what they want to do or are forced by circumstance to compromise, then I’m fine with that.

@Andy:

That is not what I am advocating for. First, you are ignoring my clarification about governing above. Second, where am I advocating for the Court to fix problems Congress won’t?

Then I would respectively ask you not to accuse me of something if you don’t know what you are accusing me of.

We agree on this more than we disagree. I think you are misreading what I am saying.

@Jay L Gischer:

I am definitely saying this.