Bush, Clinton, and Bin Laden

WaPo has two front page stories in tomorrow’s edition investigating the tepid pursuit of Al Qaeda, despite numerous attacks by that group on American targets, during the Clinton Administration.

A Secret Hunt Unravels in Afghanistan (A01):

In the years before the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the CIA carried out a secret but ultimately unsuccessful manhunt for bin Laden. It was based at first on the band of Afghan tribal agents, and later expanded to include other agents and allies, especially the legendary guerrilla leader Ahmed Shah Massoud. But the search became mired in mutual frustrations, near misses and increasingly bitter policy disputes in Washington between the Clinton White House and the CIA.

An ambitious plan for the TRODPINT team to kidnap bin Laden from his bed and hold him in an Afghan cave telegraphed the CIA’s audacity, despite what operatives saw as a restrictive mandate from the president. At the same time, the CIA’s inability to pinpoint bin Laden’s location or capture him drew pointed questions from the White House about the agency’s effectiveness.

***

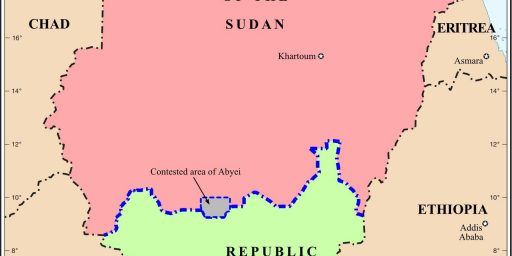

The unit had been created early in 1996 to watch bin Laden, who was then living in Sudan. By that point, the United States had decided for security reasons to close the embassy and CIA station in Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, where officers had previously been collecting intelligence about bin Laden’s financial support for Islamic radicals in North Africa and elsewhere. In the spring of 1996, Sudan yielded to international pressure to expel bin Laden. The Saudi found sanctuary in Afghanistan in May.

The CIA had no station or base in Afghanistan, however, and it had no paid agents in the country at the time, other than those hunting for Kasi near Kandahar and a few loose contacts working on drug trafficking and recovering Stinger shoulder-fired missiles, according to Tom Simons, then U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, whose account is supported by several other U.S. officials familiar with the CIA’s Afghan agent roster.

Back at Langley, the bin Laden unit transmitted reports regularly to policymakers in classified channels about threats issued by bin Laden against American targets — via faxed leaflets, television interviews and underground pamphlets. The CIA’s analysts described bin Laden at this time as an active, dangerous financier of Islamic extremism, but they saw him as more a money source than a terrorist operator.

***

As bin Laden’s bloodcurdling televised threats against Americans increased in number and menace during 1997, the CIA — with approval from Clinton’s White House — turned from just watching bin Laden toward making plans to capture him.

***

On the front lines in Pakistan and Central Asia, working-level CIA officers felt they had a rare, urgent sense of the menace bin Laden posed before Sept. 11. Yet a number of controversial proposals to attack bin Laden were turned down by superiors at Langley or the White House, who feared the plans were poorly developed, wouldn’t work or would embroil the United States in Afghanistan’s then-obscure civil war. At other times, plans to track or attack bin Laden were delayed or watered down after stalemated debates inside Clinton’s national security cabinet.

At Langley, CIA officers sometimes saw the Clinton cabinet as overly cautious, obsessed with legalities and unwilling to take political risks in Afghanistan by arming bin Laden’s Afghan enemies and directly confronting the radical Taliban Islamic militia. But at the Clinton White House, senior policymakers and counterterrorism analysts sometimes saw the CIA’s efforts in Afghanistan as timid, naïve, self-protecting and ineffective.

Some of the agency’s efforts involved intelligence collection about bin Laden’s whereabouts; others grew into covert actions designed to capture or kill leaders of bin Laden’s al Qaeda network. Both tracks were carried out in deep secrecy mainly by career clandestine service officers in the CIA’s Counterterrorist Center and the Near East Division of the agency’s Directorate of Operations.

and Policy Disputes Over Hunt Paralyzed Clinton’s Aides (A17):

There was little question that under U.S. law it was permissible to kill bin Laden and his top aides, at least after the evidence showed they were responsible for the attacks on U.S. embassies in Africa in 1998. The ban on assassinations — contained in a 1981 executive order by President Ronald Reagan — did not apply to military targets, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel had previously ruled in classified opinions. Bin Laden’s Tarnak Farm and other terrorist camps in Afghanistan were legitimate military targets under this definition, White House lawyers agreed.

Also, the assassination ban did not apply to attacks carried out in preemptive self-defense — when it seemed likely that the target was planning to strike the United States. Clearly bin Laden qualified under this standard as well.

Clinton had demonstrated his willingness to kill bin Laden, without any pretense of seeking his arrest, when he ordered the cruise missile strikes on an eastern Afghan camp in August 1998, after the CIA obtained intelligence that bin Laden might be there for a meeting of al Qaeda leaders.

Yet the secret legal authorizations Clinton signed after this failed missile strike required the CIA to make a good faith effort to capture bin Laden for trial, not kill him outright.

From Director George J. Tenet on down, the CIA’s senior managers wanted the White House lawyers to be crystal clear about what was permissible in the field. They were conditioned by history — the CIA assassination scandals of the 1970s, the Iran-contra affair of the 1980s — to be cautious about legal permissions emanating from the White House. Earlier in his career, Tenet had served as staff director of the Senate Intelligence Committee and director of intelligence issues at the White House, roles steeped in the Washington culture of oversight and careful legality.

Tenet and his senior CIA colleagues demanded that the White House lay out rules of engagement for capturing bin Laden in writing, and that they be signed by Clinton. Then, with such detailed authorizations in hand, every one of the CIA officers who handed a gun or a map to an Afghan agent could be assured that he or she was operating legally.

As the months passed, Clinton signed new memos in which the language, while still ambiguous, made the use of lethal force by the CIA’s Afghan agents more likely, according to officials involved. At first the CIA was permitted to use lethal force only in the course of a legitimate attempt to make an arrest. Later the memos allowed for a pure lethal attack if an arrest was not possible. Still, the CIA was required to plan all its agent missions with an arrest in mind.

Some CIA managers chafed at the White House instructions. The CIA received “no written word nor verbal order to conduct a lethal action” against bin Laden before Sept. 11, one official involved recalled. “The objective was to render this guy to law enforcement.” In these operations, the CIA had to recruit agents “to grab [bin Laden] and bring him to a secure place where we can turn him over to the FBI. . . . If they had said ‘lethal action’ it would have been a whole different kettle of fish, and much easier.”

Berger later recalled his frustration about this hidden debate. Referring to the military option in the two-track policy, he said at a 2002 congressional hearing: “It was no question, the cruise missiles were not trying to capture him. They were not law enforcement techniques.”

The overriding trouble was, whether they arrested bin Laden or killed him, they first had to find him.

Citing only the second article (the first may not have been posted yet), Andrew Sullivan concludes,

The Clinton administration’s feckless attempts to get Osama are, to my mind, a huge neon warning about what might happen if John Kerry becomes president.

Kevin Drum responds,

The reason for the difference between the Clinton and Bush approaches to killing or capturing Bin Laden should be obvious to everyone: 9/11. A full-scale military solution simply wasn’t on the table before 9/11 and would have had no public support. So Clinton did what he could: he authorized covert CIA action against Bin Laden, but he did so within the legal restrictions against assassination that existed at the time.

Reading the two WaPo pieces together, though, it becomes rather clear that this was more a CIA failure–an especially a failure of leadership from DCI George Tenet–than political bungling from the White House.

It’s certainly true that a George Bush-style war on terrorism would have been politically impossible pre-9/11. It has often been remarked that, if we had known all the details about the WTC and Pentagon attacks on September 10, 2001, it would have been very difficult to have done much about it under the rules of our extant criminal justice system. Indeed, we can’t muster the political will to treat Muslim males between the ages of 20 and 35 differently than little old Jewish ladies now.

As the “Secret Hunt” piece makes clear, the nature of Osama bin Laden’s role in al Qaeda was murky for years. It’s also true that, by the time we started to understand it, Clinton’s options were limited because of the scandals created by his own misdeeds. Most of us on the Right were immensely critical of any use of force at that point in the game because it appeared to be a cyncial move to divert attention from his scandals. Indeed, that view wasn’t limited to Republicans, as this blistering piece by Christopher Hitchens in Salon, responding to the missile strikes on Afghanistan and Sudan proves:

On Aug. 20, President Clinton personally ordered the leveling of the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical plant on the outskirts of Khartoum. More or less simultaneously, another flight of cruise missiles was dropped on various parts of Afghanistan and also — who’s counting? — Pakistan, in an apparent effort to impress the vile Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden, of course, hopes to bring a “judgmental” monotheism of his own to bear on these United States, and is thus in some peoples’ minds a sort of Arab version of Ken Starr.

Sources in U.S. Intelligence apparently claimed that there was only one “window” through which to strike at bin Laden, and that the only time they could hope to hit his Afghan fastness by this remote means was on the night of Monica Lewinsky’s return to the grand jury. Let’s assume they were correct. After all, they helped build and equip his camps and they may know something we don’t (even if they ended up missing him). Furthermore, the hideous Taliban regime is not available for the receiving of diplomatic notes, has even executed some Iranian envoys and seems in other ways to be deaf to shame.

***

Well then, what was the hurry? A hurry that was panicky enough for the president and his advisers to pick the wrong objective and then, stained with embarrassment and retraction, to refuse the open inquiry that could have settled the question in the first place? There is really only one possible answer to that question. Clinton needed to look “presidential” for a day. He may even have needed a vacation from his family vacation. In any event, he acted with caprice and brutality and with a complete disregard for international law, and perhaps counted on the indifference of the press and public to a negligible society like that of Sudan, and killed wogs to save his own lousy Hyde (to say nothing of our new moral tutor, the ridiculous sermonizer Lieberman). No bipartisan contrition is likely to be offered to the starving Sudanese: unmentioned on the “prayer-breakfast” circuit.

Certainly, in that atmosphere, a full-out invasion was impossible.*

A taint-free Clinton, to the extent he understood that the war on terrorism which he declared was real rather than merely rhetorical, could have almost certainly used his persuasive skills to take the country to war. But, under the circumstances, it would have been quite difficult indeed.

*I don’t say this to exonerate Clinton. This cloud of suspicion–which I thought wholly justified given my opinion of Clinton’s character–was a prime reason I believed Clinton should have been removed from office. But given that Clinton didn’t resign his post, the situation was what it was.

These are excerpts from a book. Hopefully, when the whole book is released, we’ll have a better take on his entire thesis.

However, I wouldn’t blame it all on the CIA. At least, not yet. Maybe they screwed up, but I’m not sure that’s clear yet.

And as for Clinton’s problems, I think that’s a red herring. Even if he had been as pure as Caesar’s wife, I don’t think *anyone* was actively supporting large scale military solutions to terrorism at that point. It just flatly wasn’t feasible, Monica or not.

After all, it would have required a declaration of war against Afghanistan and (maybe) Pakistan. Before 9/11, that wouldn’t have gotten five votes in the Senate.

heh- The fact that bin Laden should have been taken out and that Bill Clinton was trying to distract people ain’t mutually exclusive.

There’s both true.

I’ve heard mixed information on how much we knew about the pharmaceutical factory. It appeared at the time like an action more flamboyant than aggressive. More flashy than serious. I still think if we’d had a focused President with some will, things might have turned out differently.