Evangelical Politics in the Time of Polarization and Covid

A piece in The Atlantic inspires thoughts.

A post in one of last weekend’s open fora pointed me to this Atlantic piece by Peter Wehner, The Evangelical Church is Breaking Apart. The piece is a lament by the author of what he sees as growing acrimony and conflict within Christian churches, and specifically of the evangelical type that he has long attended. I think that his concerns are heartfelt and genuine and that he sees a real degradation of the positive aspects of his faith community. I was struck, however, as how the scenario he describes are indicative of broader socio-political realities as linked to issues like Covid, the role of social media/cable news, and partisanship more broadly.

The post is much longer than I intended (especially since I initially had put in it a draft tab-clearing post!) but as I wrote I ended up reflecting on some onf own personal experiences with evangelicalism, as well as having a minor a ha! moment about why I was wrong about evangelicals and Trump back in the 2015/2016 period. I was raised a Southern Baptist and attended evangelical churches well into adulthood. My current religious views are far more heterodox these days, but I speak fluent Evangelical.

So, here we go.

At its root, I think that the article is illustrating the way in which politics and media have become increasingly confrontational. I think, further, that the pandemic has created general tension, but also is part of the broader partisan divide.

Here is how Wehner describes the situation, which underscores the general societal tensions we area all dealing with:

The key issues in these conflicts are not doctrinal, Fryling told me, but political. They include the passions stirred up by the Trump presidency, the legitimacy of the 2020 election, and the January 6 insurrection; the murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement, and critical race theory; and matters related to the pandemic, such as masking, vaccinations, and restrictions on in-person worship. I know of at least one large church in eastern Washington State, where I grew up, that has split over the refusal of some of its members to wear masks.

[…]

In his own church, some of the elders are devoted to culture-war politics. “These guys can be a special kind of relentless, and I don’t think I’ve had it as bad as many,” he said. “But when we’re stressed out, trying to be public-health experts without the training to do that, trying to keep our own families from blowing up with COVID stress, getting criticized from both sides at once, and then having folks doing whatever they can to ruin us and get us run out of town— we’d love to just be trusted as friends and shepherds. I understand why many folks have just said, ‘I’m done.’ I’m not there yet, but I hardly think I’m above it or guaranteed not to. I just pray to Jesus to not let me throw in the towel.”

But, of course, as Wehner notes:

But there’s more to the fractures than just COVID-19. After all, many of the forces that are splitting churches were in motion well before the pandemic hit. The pandemic exposed and exacerbated weaknesses and vulnerabilities, habits of mind and heart, that already existed.

More telling, really, is the anecdote that starts the piece, which is about an Elder election at McLean Bible Church, which is described as “an influential megachurch in Northern Virginia.”

[Pator David] Platt, who is theologically conservative, had been accused in the months before the vote by a small but zealous group within his church of “wokeness” and being “left of center,” of pushing a “social justice” agenda and promoting critical race theory, and of attempting to “purge conservative members.” A Facebook page and a right-wing website have targeted Platt and his leadership. For his part, Platt, speaking to his congregation, described an email that was circulated claiming, “MBC is no longer McLean Bible Church, that it’s now Melanin Bible Church.”

We see here, in my view, the clear politics of racial resentment and the deep influence of right-wing media wherein “wokeness” has become an insult and where any suggestion of justice on racial grounds is seen as some kind of leftist nonsense.

Heaven help any member of the church for saying woke things like “Faith in Christ Jesus is what makes each of you equal with each other, whether you are a Jew or a Greek, a slave or a free person, a man or a woman.” That is clearly crazy woketalk. And please, none of this: “Treat others as you want them to treat you. This is what the Law and the Prophets are all about.” And especially not this: “The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself.”

I mean, seriously, what is this place, some kind of long-haired hippy socialist comune?

Next, someone is going to say “love one another” and tell us to do nice things for the poor.

I mean, come, on. How woke can you get?

Allow me to define the term as I am using it here,* as I recall there being some debate about this in some comment thread not that long ago. I am speaking here of churches that hold at least the following views: the concept of the authority of inerrant, God-authored scripture; the idea that God is sovereign, omnipotent, omniscient, and in control of everything; and the idea that salvation comes through acceptance of the Lordship of Jesus Christ (and that He is part of the triune God, i,.e., the Holy Trinity, God in three persons: the Son of the Holy Trinity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit). Salvation is key because of the affiliated belief in eternal life after death. The saved go to Heaven, to live forever with God, while the unsaved go into eternal torment in Hell. If one believes this life is but a blip in eternity, and that one’s choices (and the choices of others) determine whether one is going on to eternal bliss or eternal torture can shape one’s worldview rather significantly (and can explain a lot of behavior). Evangelical theology also includes notions of the end times, when Christ will return to Earth and restore His kingdom, and that idea also contains a lot of suffering before said return.

The groups that fall into this camp include the aforementioned Southern Baptists, most “Bible churches,” a host of nondenominational mega-churches, and includes some, but perhaps not all, churches in a number of mainline denominations such as Methodists. This is not intended to be a comprehensive list.

Let me note that I am discussing these issues as sociological and political** phenomena. It is a fact that many (if not most) human beings have religion, and it is historically the norm is for religion and politics to be associated, if not fused (there is a reason that the concept of “separation of church and state” had to be invented, for example–and that the management of that concept is inherently political). It is further a fact that religious views impact behavior, both positively and negatively. (So note, I am hoping that whatever discussion in the comment section blossoms is not just evangelical-bashing***).

We can turn to survey data to see some of these notions in the wild, so to speak:

In regards to the notion that God is in control, let me note this following from a piece by Natalie Jackson at FiveThirtyEight (Why Some White Evangelical Republicans Are So Opposed To The COVID-19 Vaccine):

The belief that God controls everything that happens in the world is a core tenet of evangelicalism — 84 percent of white evangelicals agreed with this statement in PRRI polling from 2011, while far fewer nonwhite, non-evangelical Christians shared this belief. The same poll also showed that white evangelicals were more likely than any other Christian group to believe that God would punish nations for the sins of some of its citizens and that natural disasters were a sign from God. What’s more, other research from the Journal of Psychology and Theology has found that some evangelical Christians rationalize illnesses like cancer as God’s will.

[…]

PRRI’s March survey found that 28 percent of white evangelical Republicans agreed that “God always rewards those who have faith with good health and will protect them from being infected with COVID-19,” compared with 23 percent of Republicans who were not white evangelicals. And that belief correlates more closely with vaccination views among white evangelical Republicans — 44 percent of those who said God would protect them from the virus also said they would refuse to get vaccinated. That number drops to 32 percent among Republicans who are not white evangelicals.

Jackson also notes end times issues:

the pandemic also fits neatly into “end times” thinking — the belief that the end of the world and God’s ultimate judgment is coming soon. In fact, nearly two-thirds of white evangelical Republicans (64 percent) from our March survey agreed that the chaos in the country today meant the “end times” were near. Faced, then, with the belief that death and the end of the world are a fulfillment of God’s will, it becomes difficult to convince these believers that vaccines are necessary. Sixty-nine percent of white evangelical Republicans who said they refused to get vaccinated agreed that the end times were near.

Regardless of one’s view of the beliefs and practices of a given religion, there is little doubt that religious views impact worldviews (indeed of how life should be lived, which certainly directly intersects with all aspects of human interaction) and, therefore, all things political. This is especially true in places with a state religion or, where religious views are directly associated with a given political party or some other significant social cleavage (e.g., ethnicity, geography, etc.) in a given society

To bring this back to the specific topic at hand: there is an exceptionally strong relationship between evangelical churches and Republican partisanship, especially in the last several decades. This relationship dates back to at least the 1970s and it is linked to both desegregation and abortion (among other issues). At that time it was mostly a presidency-level phenomenon, given the fact that Republicans were not competitive at the state level in the deep south as I have pointed out on numerous occasions, such as here and here. So, for example, it should be noted that in, say, 1984, a conservative evangelical in a southern state very likely voted Democratic for every office except president (and that behavior contained in some states until well into the 2000s).

Having said that, let me note, anecdotally, that my experience in the mid-1980s and very early 1990s in the evangelical circles in which I ran, was the view was that it was unlikely that Democrats were “real” Christians (because abortion). There was also a bunch of silly theological parsing of who was, and was not, a real Christian–a game the Evangelicals like to play because the stakes were so high in regards to eternity and all that. I would note that most of what I am describing I experienced in Southern California. Such attitudes were not as prevalent in my youth in places like Temple and Waco, Texas. This is simply because at that point in time, most sub-presidency partisanship in conservative Texans was Democratic, not Republican.

There was a multi-decade build-up, starting really in the 1960s with opposition to civil rights legislation, and escalating with the Moral Majority and Reaganism in the 1970s into the 1980s that finally culminated in the 1994 mid-terms and the full merging of US conservativism, including white evangelicalism, into the Republican Party coalition that we have today, with its red states and blue states and all that connotes in our current politics.

Indeed, part of the story here is the way in which the regional realignment of the parties led to the deep connectivity between white evangelicals and Republicanism (remember: Jimmy Carter, a Democrat elected in 1976, was a self-proclaimed born-again Christian, whose bona fides in that arena are hard for any other president to beat). While the connection of conservative politics and evangelicalism is older, these days the overlap between “evangelical” and “Republican” is pretty strong, as Jackson notes from her survey data:

given how many white evangelicals identify as Republican or lean Republican — about 4 in 5 per our June survey — disentangling evangelicals’ religious and political beliefs is nearly impossible.

This fact is important to know in and of itself, as it is an important empirical observation about the nature of the GOP’s coalition. This also intersects with my ongoing discussions of the power of partisanship. The mixture of strong religious identity and strong partisan identity is pretty potent. As Wehenr writes in his piece:

For many Christians, their politics has become more of an identity marker than their faith. They might insist that they are interpreting their politics through the prism of scripture, with the former subordinate to the latter, but in fact scripture and biblical ethics are often distorted to fit their politics.

What is telling in the Wehner article is the degree to which in this relationship between politics and theology, that politics is more influential than theology (which has been my personal experience as well):

“Nearly everyone tells me there is at the very least a small group in nearly every evangelical church complaining and agitating against teaching or policies that aren’t sufficiently conservative or anti-woke,” a pastor and prominent figure within the evangelical world told me. (Like others with whom I spoke about this topic, he requested anonymity in order to speak candidly.) “It’s everywhere.”

Wehner notes why, in this context, he wrote the piece:

The aggressive, disruptive, and unforgiving mindset that characterizes so much of our politics has found a home in many American churches. As a person of the Christian faith who has spent most of my adult life attending evangelical churches, I wanted to understand the splintering of churches, communities, and relationships. I reached out to dozens of pastors, theologians, academics, and historians, as well as a seminary president and people involved in campus ministry. All voiced concern.

The problem is, to restate what I said above, politics has a way of melding with theology (in a way that politics tends to dominate):

The root of the discord lies in the fact that many Christians have embraced the worst aspects of our culture and our politics. When the Christian faith is politicized, churches become repositories not of grace but of grievances, places where tribal identities are reinforced, where fears are nurtured, and where aggression and nastiness are sacralized. The result is not only wounding the nation; it’s having a devastating impact on the Christian faith.

This is not surprising to me, to be honest. While the religious like to think that the power of the divine will lead to religion dominating the political and the social, the reality is that the power interests of partitioners are more likely to shape what part of their theology that they wish to embrace. Note the embrace of chattel slavery by a large number of American Christians until they were literally forced not to (and then Jim Crow, and so forth).

Scott Dudley, the senior pastor at Bellevue Presbyterian Church in Bellevue, Washington, refers to this as “our idolatry of politics.” He’s heard of many congregants leaving their church because it didn’t match their politics, he told me, but has never once heard of someone changing their politics because it didn’t match their church’s teaching. He often tells his congregation that if the Bible doesn’t challenge your politics at least occasionally, you’re not really paying attention to the Hebrew scriptures or the New Testament. The reality, however, is that a lot of people, especially in this era, will leave a church if their political views are ever challenged, even around the edges.

“Many people are much more committed to their politics than to what the Bible actually says,” Dudley said. “We have failed not only to teach people the whole of scripture, but we have also failed to help them think biblically. We have failed to teach them that sometimes scripture is most useful when it doesn’t say what we want it to say, because then it is correcting us.”

In my experience, that is not a new phenomenon, a fact backed by the historical record, I would argue.

In other words, I am not so sure that it hasn’t always been thus, going back (at least in terms of Christendom) to the way Roman-occupied Palestinian Jews saw Jesus, to the way the Roman Emperors used Christianity as a tool, to Henry the VIIth founding the Anglican Church to get out from under the thumb of Rome, to Jerry Falwell, Jr. (to note some broad brushstroke history).

I get it (I really do): from a Christian perspective, especially a fundamentalist one, there is this hope that the power of the divine can transcend human nature and hence the power politics and identity. Alas, the evidence of this is pretty scant (at least in my own observation both as personal experiences and in terms of historical events). To pick a really easy example: it is hard to believe that the organized seeking of the divine leads to transformative behavior when one sees things like the widespread scandals involving Catholic priests molesting children in their care (or, for that matter, similar issues with the SBC or even specific cases like Ravi Zacharias, who was the type of theologian that young me, with his desire for an intellectualize Christianity, was drawn to).

Please note, the central pillars of Christianity have some serious positivity, as I noted above. To quote the gospel according to Douglas Adams, “how great it would be to be nice to people for a change” is a pretty nice sentiment. Further, the foundational story is one of sacrifice in the name of unconditional love. I am not knocking any of that.

Still, I digress a bit in what is already a long post.

To be honest, the thing that got me starting to write was the following short paragraph (the minor “a ha!”moment I noted at the beginning), because I think it is key to much of what Wehner is writing about, but it really is, in my view, inadequately explored in the piece:

Many Christians, though, are disinclined to heed calls for civility. They feel that everything they value is under assault, and that they need to fight to protect it.

Speaking as someone who grew up in Evangelical churches and attended them well into adulthood, these churches have been cultivating the notion that the church is “persecuted” and how “the world” hates Christians because it hates Christ. This is a seed long sown and the harvest is being seen in that article (along with other problems as well). I have personally heard this since the late 1970s.

I very vividly remember being told things like that American Christians were practically as persecuted as the martyrs of the early church or like Christians in authoritarian countries who had to worship in secret. I also recall, even in my youth, wondering how that could be so, if there were churches, well, everywhere.

I still find it baffling and amusing to hear people in Alabama talk as if public schools are rife with anti-Christian activity (when, in fact, the public schools are overwhelmingly populated with teachers who regularly attend church). Everyday life in this state is very much influenced by a significant amount of cultural Christianity, and yet a lot of folks really do believe that they are persecuted for their faith.

But, look, if you are told by figures of moral authority that you are being persecuted, you are likely to believe it. Hence, you get things like “The War of Christmas” and a lot of people believe it, despite the fact that the national calendar is shaped around the high holy days of Christianity, ie., Easter and, most especially, Christmas.

I think this long-term stoking of grievance, coupled with demographic changes and power shifts on things like gender, primed white Evangelicals for Trump far more than I realize back in 2015/2016 (indeed, I argued at the time that Evangelicals would not vote for a twice-divorced, casino-owning vulgarian, and so he could not possibly be nominated). Clearly, I was super wrong on that count.

The entire gay marriage issue clearly was seen by a lot of Christians as an assault on their “Biblical views of marriage” as exacerbated by issues like the confrontation over wedding cakes and photographers. Without getting into these arguments, it was very much the case that even serious evangelicals saw the whole thing as an assault on their values, and even their religious liberty. Several years ago I had lunch with a friend of mine who is a Baptist pastor, and one who very much take issues like racial justice very seriously (indeed, he left the pulpit for a whole to work in the area of immigrant advocacy) saw the whole gay marriage issue as a threat to religious liberty. Before Trump ran he was worried about the federal government using the tax-exempt status of churches as leverage to force churches to perform same-sex weddings. Now, I argued then, and still believe, that that is not going to happen, but he thought it to be a real threat. Again: this is a person who is smart, rational, and concerned about social justice issues. My point being, and, again, without getting into the merits of the argument, saw gay marriage as a threat to religious liberty, what did the average Baptist think back when the Obergefell came down?

You can throw in the shifts norms on gender (like same-sex bathrooms), movements to allow trans persons to participate in high school sports based on their self-identity, and even things like pronouns wars and it is not hard to get people all spun up. And before someone tells me this is just Fox News getting people upset (and they definitely have their role), I have had liberal people make private comments to me that seeing someone up their pronouns in their e-mail signature blocks annoys them.

People don’t like change, as the cliche goes, but cliche or not, it is true, and they especially don’t like change that affects their power (real or perceived).

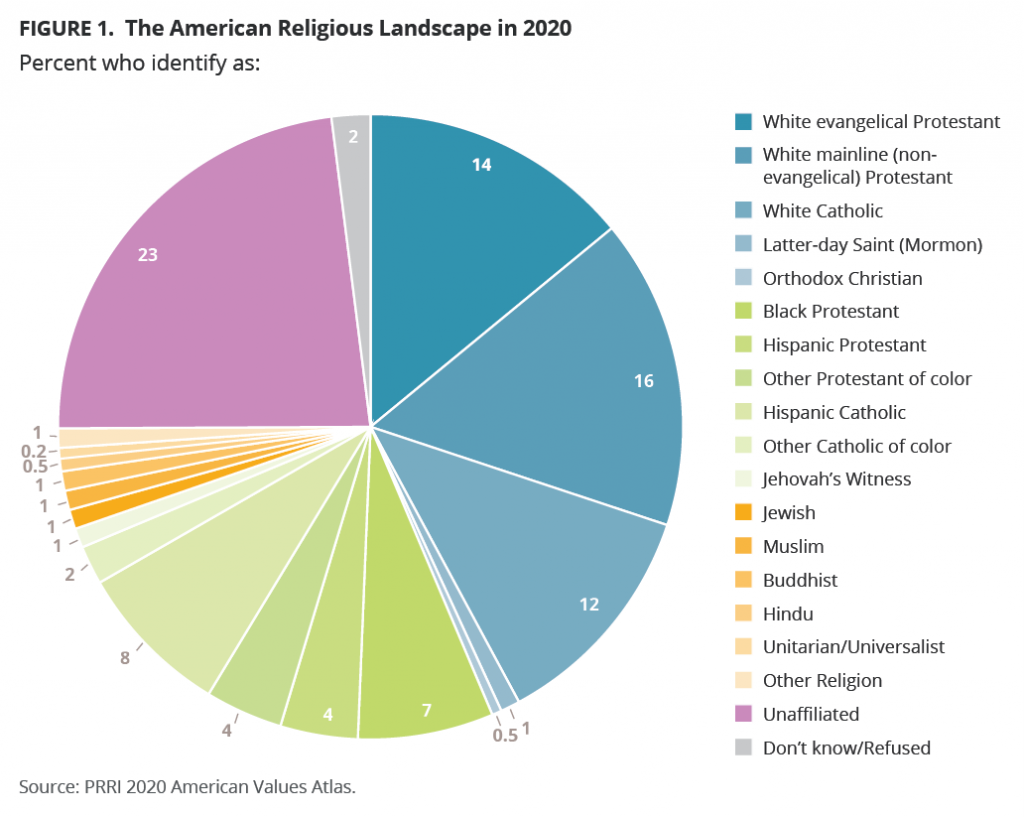

Christianity has been I(and really, still is) the dominant religion in the US and had deep cultural significance. To stick with PRRI, its 2020 survey found that 70% of American identify as “Christian” (which is similar to Pew’s 2014 Religious Landscape Survey, which put the number at 70.6%). PRRI identifies 14% as “white evangelical.” Here’s breakdown:

I think the most telling way to slice the data is this (emphasis mine):

The most substantial cultural and political divides are between white Christians and Christians of color. More than four in ten Americans (44%) identify as white Christian, including white evangelical Protestants (14%), white mainline (non-evangelical) Protestants (16%), and white Catholics (12%), as well as small percentages who identify as Latter-day Saint (Mormon), Jehovah’s Witness, and Orthodox Christian[2]. Christians of color include Hispanic Catholics (8%), Black Protestants (7%), Hispanic Protestants (4%), other Protestants of color (4%), and other Catholics of color (2%)[3]. The rest of religiously affiliated Americans belong to non-Christian groups, including 1% who are Jewish, 1% Muslim, 1% Buddhist, 0.5% Hindu, and 1% who identify with other religions. Religiously unaffiliated Americans comprise those who do not claim any particular religious affiliation (17%) and those who identify as atheist (3%) or agnostic (3%).

Race in America is about power in America and as whites see their power declining, even in a relative sense, they will act as political actors in such circumstances: they will seek to protect their power.

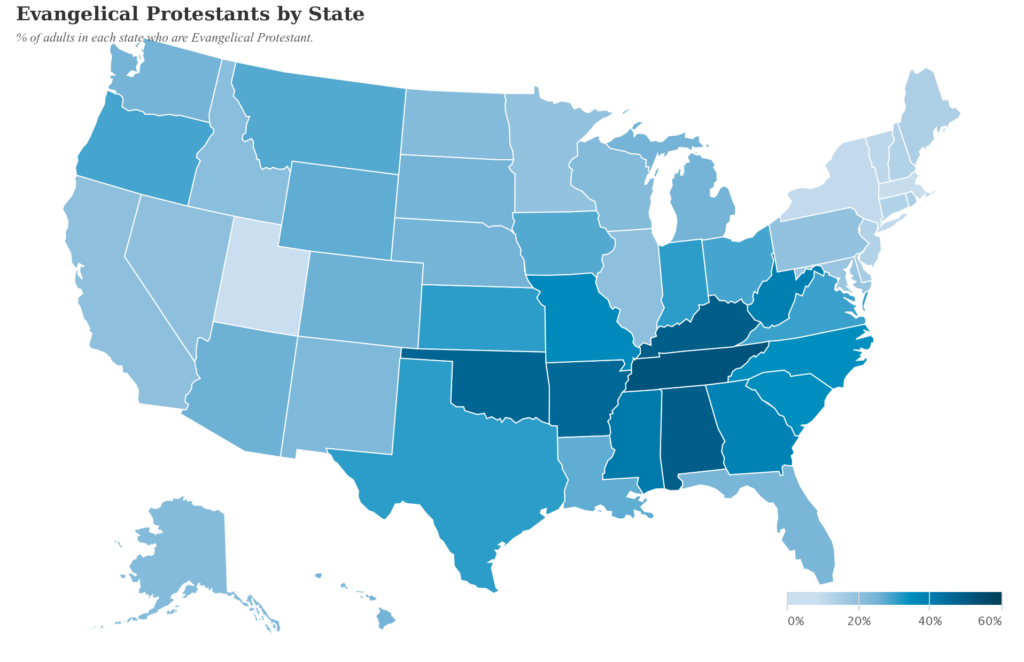

I would vote, too, using the Pew study, that self-identified evangelicalism has some significant geographical concentration:

Recall above that I noted that the political significance of religion is amplified when it is concentrated with other social cleavages like race and geography. While the concentrations are not perfect, they are significant. Race, religion, and geography are self-reinforcing cleavages in American politics.

Hence, the appeal of Trump to evangelicals becomes more clear. They felt/feel threatened, and these feelings are reinforced by overlapping social cleavages (reinforced further, I would add, by the role that states as units play in electing the president and the Senate).

So, one may ask, what’s the point? I think that the most fundamental point is to understand that apart from whatever metaphysical attributes one wants to assign to religion it should be understood as part of the broad constellation of inputs into the political views of the populace and, more importantly, is very much about power (after all, what is more powerful than being in the position to determine right and wrong, not to mention questions of eternity?).

As it pertains to Trump, I have long understood why evangelicals embraced him once he was nominated–that was fundamentally partisanship (see, again, the numbers from the Jackson article noted above–to be a white evangelical almost certainly means on is a partisan Republican and once nominated, Trump was the only partisan game in town). In regards to evangelical support for Trump in the primaries, which was key to his winning the nomination, I guess the best answer is a preference for a fighter who would give voice to perceived grievance. You tell people that they are persecuted long enough, they will believe you, regardless of reality (and they will also see any loss of power as proof of that persecution). Trump, like other authoritarians, convinced a dominant group with relative power decline that strong measures were needed to shore up their position. (See, also, the whole current brouhaha over CRT–which is being cast as being a way to diminish white people–ditto immigration and the border crisis).

Wehner also notes this:

But of course Trump did not appear ex nihilo. Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a history professor at Calvin University and the author of Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, argues that Trump represents the fulfillment, rather than the betrayal, of many of white evangelicals’ most deeply held values. Her thesis is that American evangelicals have worked for decades to replace the Jesus of the Gospels with an idol of rugged masculinity and Christian nationalism. (She defines Christian nationalism as “the belief that America is God’s chosen nation and must be defended as such,” which she says is a powerful predictor of attitudes toward non-Christians and on issues such as immigration, race, and guns.

Du Mez told me it’s important to recognize that this “rugged warrior Jesus” is not the only Jesus many evangelicals encounter in their faith community.

As it pertains to the thesis of Wehner’s article, I think he is seeing evangelical churches reaping what they sowed: embracing Fox News and its grievance-churning style and then hitching its wagon to a pugilistic vulgarian. It is not surprising that both are going to lead to the kinds of conflict that he details. And it isn’t going to get any better because the feelings of grievance (see: Covid) are not getting better. Indeed, they are getting worse.

*This 2018 piece from Christianity Today does a good job of defining and placing some historical context: What Is Evangelicalism? See, also this 2015 piece fromThe Atlantic: Defining Evangelical.

**”Political” as broadly defined, for those who might think the term narrowly applies to the acts of politicians or government. At a minimum, there is a clear linkage between power and religion that puts it in a political space, but the context of this post, and some of the numbers cited herein, should also make clear the political aspects of the issue.

***Which is to say if all one can say about religion is that it is stupid and that the religious are stupid then that is not a welcome nor helpful comment. I say this not because such statements would insult me (they would not), but because they are simplistic and not helpful. The preponderance of humanity over time has been religious (and still is). It simply is not the case that only the non-religious (or, even, non-evangelical) are smart and rational (or however one wants to characterize them). Have terrible things been done in the name of religion? Of course. But it isn’t like the non-religious have no blood on their hands.

It would be, oh, about 40 years ago that I started saying that when politics and religion go into a room together, only one comes out alive. Politics will trump religion for a couple of excellent reasons:

1) Politics is more about money (taxes, benefits) than even religion, and money is the true American faith.

2) Christians have never believed the bullshit they pretend to believe. Saying you’re a Christian is easy and used to be profitable. Actually being a Christian is hard and not profitable. See point #1 above.

Religion is codified irrationality, a suspension of disbelief, a deliberate avoidance of reality. Obviously if your basic programming is irrational your subsequent decisions are far more likely to be irrational as well. GIGO. And when your version of Christianity is evangelical – denominations nearly devoid of actual theology, the dumbest iterations of Christianity – you’re mentally unprepared for just about any change in the status quo. What you do have is a whole big heap of certainty and self-righteousness joined with irrationality, which breeds frustration, anger and violence.

And a quibble: yes race is a big part of this, but I think sex is a bigger driver. What we are seeing is largely male panic.

I may have missed it, but how is “unaffiliated” defined? I’m certainly unaffiliated, given that I wasn’t raised in any religion. I have, however, a demented/evil acquaintance who’s a fanatic believer but doesn’t attend any church, and a niece-in-law who proudly proclaims herself a Christian first and foremost who also doesn’t, as far as I can tell, attend any church nor consider herself a member of any denomination. Both these loons could be considered “unaffiliated.”

Religion + Politics = Politics

Religion + Murdoch Media Conglomerate = Hell on Earth

I also grew up in evangelical churches but probably more conservative and near cult like than you did. My family is still heavily involved. I think the big change is the total embrace of politics. I think there are many that still have sincere religious beliefs but at this point I dont think a lot of them are capable (willing?) of separating religious belief from political. However much you think that evangelical leaders and churches are tied into GOP politics it is probably worse than you think. Religion doesnt get covered in most media so a lot happens unnoticed. If you are really interested in the topic I would suggest reading David Kuo’s book Tempting Faith. Bush and co pretty routinely broke election rules knowing they would not be found out. Those famous, manly, evangelical leaders came in an groveled to Bush.

Steve

@CSK: A quick check of the interwebs shows almost 1 in 4 people claim “no religion” in the US (23.1%), so it looks like “unaffiliated” for this poll might include you. If it’s only a poll of people who claim a faith of some sort, “unaffiliated” would be people like your relatives who claim a faith but don’t belong to a denomination. It’s possible that the no religion/unaffiliated cohorts overlap and the religious landscape cohort is a similarly scaled subset of a larger no religion group.

Interesting to note that in Korea the percentage of people who assert no belief in a religion is also roughly 20%–at least according to the data I looked up while I was living there.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

Only one is a relative, and that’s only by marriage, for which I give hearty thanks. The other one I stopped having anything to do with 20 years ago. Insane and evil does not appeal to me.

I’ve said before that I really don’t fathom people who loudly proclaim their Christianity, but who don’t identify with any denomination or go to any church.

I understand people who aren’t believers but who affiliate with a denomination for the perceived social or financial advantages that may accrue. It’s crass and cynical and opportunistic, but I get the motives behind such a move.

Well, these Christians aren’t wrong.

Because “everything they value” isn’t just being a Christian and getting saved in the afterlife. Rather, it’s the ability to impose their values on everyone else in this life.

In other words, religion isn’t just religion, it is also (moreso, I’d argue) politics, i.e., the exercise of power (both formal and informal) in order to shape a political community.

Christians are losing that battle – or, at the very least, the hearts and minds part of that fight.

And because they can’t accept losing, they are changing the rules. “Real America,” “a republic, not a democracy,” yada, yada.

Your shout-out to Douglas Adams is apt. Adams (an atheist BTW) notes that Christ was nailed to a tree for that radical notion of being nice to people for a change.

History repeats itself. The Pharisees saw Christ as a extreme threat to their power with all his crazy talk about loving your neighbor as yourself. He was killed for his heresy. Today’s Pharisees do the same when they somehow twist social movements seeking equal treatment for all (Jew or a Greek, a slave or a free person, a man or a woman) into persecution of themselves. Who’s going to be crucified this time around?

There is so much that is self-contradictory in evangelicalism. The discussion of evangelicals’ refusal of the covid vaccine is exemplary in that regard. Do evangelicals reject all vaccines because God will protect them? Why are so many of them armed, if God will protect them from evil people? Same thing if it doesn’t matter because the end of the world is coming.

One of the snips above contains a quote that almost accuses evangelicals of heresy. Recently, a retired head of one of the Baptist denominations actually used that word in regard to some of the nonsense going on in these churches now.

A saving grace (yes) is that many of the young people actually believe that hippy-dippy woke stuff and are leaving these bastions of hate and racism. Can’t happen too soon for me.

@Cheryl Rofer:

Perhaps. But I have long argued that if we find that people are behaving against what they claim to believe our go-to should be “mystery” or “hypocrisy” but rather, “based on their actual behavior, their actual real world actions, let’s try to figure out what their beliefs are.” Sure, Evangelicals talk about Christianity all the time and every other word out of their mouth is “Jesus” but I think we can all agree most (not all – definitely not all) don’t demonstrate any kind of Christian behavior whatsoever. Whatever good behavior and thoughts they exhibit is severely limited to those they see as inside the circle.

So, based on behavior, what is the primary motivator of these Evangelicals. I don’t want to over simplify but I think at least 60-70% is the anger, fear and resentment of people violating social hierarchy. Twenty years ago gays were on the bottom rung and it was okay to rail against them. But now they are considered regular folks. If Evangelicals were motivated by Christian values this would make perfect sense and they . Don’t throw the first stone. Judge and you shall be judged. All that. But that’s obviously not the case.

My hypothesis is that these people are primarily motivated by social resentment but have a need to see themselves as moral. Someone inside they know that their position is the opposite of moral so they pull on a multi-colored cloak stitched together of random Christian phrases and ideas. I may be wrong, but so far I find it predicts reactions and behaviors very well

The evangelical church, which led the abolition movement in early American history, has become a front for white supremacy and corporatism. It will be topic of fascination for future historians. For us living through it, it’s a dangerous threat to the American experiment.

These fake Christians are in the midst of a self-own, because their own kids are distancing themselves from evangelical beliefs and culture. This lashing out from the Republican base is death throes. But Republicans like winning too much to not adapt and change, eventually. That won’t happen until Trump is gone.

If Democrats manage to hold onto Congress and the White House in 2022 and 2024, expect bloodletting.

@MarkedMan:

I agree with most of your comment. Especially the parts about social hierarchy and understanding people based on what they do rather than what they say.

However, I’m not so sure about this:

Looking at Christianity as it really exists/existed, why wouldn’t it be moral to hate on the gays?

These people believe themselves “moral” precisely because they hate lesser, sinful people. Looking at historical precedent, it is absolutely the Christian thing to do.

The thing that fascinated me about that article, rather than confirming my priors, is the bit where the conflict is driven by maybe 20 percent of church membership. That’s a much smaller slice than I expected.

And it reminds me to look through that lens. People are causing trouble at school board meeting about anti-covid measures. How many voters do they, in fact, represent? Maybe it’s not that many?

Most people, let alone evangelicals, are conflict averse. Which means that you can kind of dominate the agenda if you lean into conflict – taking what is sometimes called a “prophetic” stance.

Dr. T., you hit the nail on the head with all of this. Growing up as a Southern Baptist and living smack dab in the middle of the Bible Belt (that LA is Louisiana, not Los Angeles ;)), this is pretty much exactly what I have experienced and observed.

And since you speak fluent evangelical, I know you’ll get as big a kick out of this as I did when I saw it last year. Enjoy!

https://heybrobear.com/blog/church-karens-on-halloween-sums-up-your-evangelical-childhood-perfectly

(And yes, y’all, I legit know church ladies like this. :|Scary, huh?)

It’s interesting that in England the Church of England is far more formally politically connected.

(Note in this case the UK nations are distinct: Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland are very different)

Anglicanism is the Established Church. The Monarch is both Head of State and Supreme Governor of the Church of England, and Defensor Fides.

The House of Lords in Parliament includes 25 Lords Spiritual i.e. Anglican bishops; the coronation is an Anglican ceremony; episcopal appointments are (at least formally) subject to political approval.

The Church of England has been called (originally by Maude Royden) “the Conservative Party at prayer”.

These days though the Liberal Democrat Party is the Church of England at prayer 🙂

And on the other side, the Labour Party was said by Harold Wilson to be closer to Methodism than to Marxism. The first Labour Party leader, Kier Hardie, was a Methodist preacher. At the same time, Roman Catholics were also another key constituency of the Labour Party.

From all this you might expect politicised religion to be far more of a thing than in the US; but they aren’t, in practice. The whole culture of religion seems very different. I’ve mentioned before, an Anglican cleric of my acquaintance referring only half-jokingly to American evangelicals/fundamentalists having a large component of “heretics and lunatics”.

(Adherents of magisterium tend to be very dubious about literalism)

I’m inclined to agree with Wehner and French that a large element of political Christianity in the US relates more to politics and to “southern-ness” than anything else. With the additional factor that a lot of the rural/small town West/Mid-West seems to be increasingly culturally “southernized”.

The thing is, while formally established, Christianity in England has not been culturally dominant for perhaps a century, or so much intertwined with personal and political identification and social organisation.

Which has arguably made it easier for it to adapt theologically to modernity.

It will probably take a long process of political and cultural decline to reconcile southernized evangelicalism to a socially marginalised position, and perhaps to modernised traditional Christian theology.

Expect a lot of kicking and screaming in the meantime.

@Jay L Gischer:

That’s what struck me, also. White Protestants are charted above as 30% of the country. 20% of 30% is not a large number to be causing so much discord, in their congregations or nationally. There are a lot of conservative Catholics. Do Catholic congregations have these issues?

Wehner speaks of catechesis, instruction in religion, but notes that,

And I suspect it’s not just cable “news”, but also the cable preachers.

I’m also in the “raised in Southern Baptist churches” group, and I have a lifetime’s experience with the ways people who claim to study the bible closely can nevertheless come out with justifications for wildly unChristian* positions.

These days, I’ve taken to saying “Jesus was as woke as you can get. If that bothers you, you may have chosen the wrong religion. I suspect I know which side you’d have been on in Luke 23.”

*In the sense of “antithetical to what Jesus of Nazareth taught”. What the organized Christian church has stood for and practiced over the centuries is only tangentially related to that.

@drj:

That’s because for them, Evangelicalism is an all-encompassing lifestyle that demands conformity and compliance to their social and moral mores. It’s not an accident COVID denial/ anti-vaxxerism, MAGA and QAnon got absorbed so quickly by this group – they spoke a similar jargon with matching imagery and memes to boot. The social context of all of these things pushes them towards conservatism and the GOP and the GOP mutates to match the latest strain of crazy. They are very aware that without the wingnut ecosystem, their ideas can’t thrive in the wild. Thus the hatred of education, multiculturism and cities – all things that lead to questioning.

Evangelicals don’t want you to think – they want you to do as they tell you. Abdication of agency and responsibility are considered a good thing (Jesus take the wheel!!) so taking or suppressing it from others that don’t agree with them is natural.

@drj:

Damn edit button…

Technically if Paul had had his way, all sex would have been treated with the same eww-icky-sinners!! take as the gays were. He was into abstinence for everyone and it was only when they realize Jesus wasn’t returning in the immediate future that he had to deal with angry horny converts and the need to procreate new believers from within the church. 1 Corinthians 7:6 literally says it’s a concession that he’s making for believers to sleep with each other but they really, really, REALLY should be like him and pass on all of it if they could.

Otherwise a lot of is folk religion and old-school politics that bled through to become dogma. What we think of as “gay” wasn’t a thing back in older cultures so we need to understand a lot of culture and BS just got carried along for generations until it was essentially codified that same gender sex is a no-no. Hell, marriage itself wasn’t a thing for 90% of peasants until centuries after Christ died but “sanctity of marriage” as concept survives because of nobles, property issues, bloodline concerns and good old-fashioned sexism.