Is The Supreme Court Too Small?

One law professor suggests that we need to double the size of the Supreme Court. Is he right?

The end of a Supreme Court term always brings with it contemplative pieces from legal analysts, law professors, and basically just anyone who thinks they have something to say about America’s highest court. This seems to be especially true this year given the fact that the Justices are on the verge of ruling on several high profile and controversial cases, including Arizona’s immigration law and, of course, the Patient Protection And Affordable Care Act. I’ve already discussed several of those pieces here over the past week or so, but perhaps the most interesting, and radical, appeared in Sunday’s Washington Post, where George Washington University Law Professor Jonathan Turley argues that the size of the Supreme Court should be expanded dramatically:

It could all be in the hands of just one justice. After a 14-month fight in Congress and an unprecedented challenge by states to the power of the federal government, the fate of health care in this country is likely to be decided by a 5-4 vote.

The same may be true when the court rules on Arizona’s immigration law and a sweeping free speech case.

As speculation and anxiety grow over these cases, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg recently alluded in a speech to “sharp disagreement” in the Supreme Court’s outstanding opinions, while saying that “those who know don’t talk, and those who talk don’t know.”

It’s not terribly productive to try to guess how the court will rule in these cases — we’ll find out soon enough. It’s far more important to ask whether “those who know” are too few and whether “those who don’t know” should demand to reform the court.

The power of the Supreme Court will always be controversial because of the fact that the justices are the final word in legal disputes. Justice Robert Jackson wrote in 1953, “We are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final.” An individual’s view of the court can depend on whose ox is being gored by its decisions; a “judicial activist” is often just a jurist who doesn’t do what you want. Any Supreme Court of any size will always render unpopular decisions. It is supposed to. Federal judges are given life tenure to insulate them from public opinion, so they can protect minority interests and basic liberties.

But how many people should it take to come up with the final word on such questions? Our highest court is so small that the views of individual justices have a distorting and idiosyncratic effect on our laws. The deep respect for the Supreme Court as an institution often blinds us to its flaws, the greatest of which is that it is demonstrably too small. Nine members is one of the worst numbers you could pick — and it’s certainly not what the founders chose. The Constitution does not specify the number of justices, and the court’s size has fluctuated through the years. It’s time for it to change again.

This part of Turley’s argument strikes me as particularly weak. The fact that the Supreme Court is a relatively small institution does not, by itself, mean that it is as much a product of the “distorting” views of individual justices as Turley suggests. One need only look at some of the decisions that were released last week to find evidence of that. Granted, not all of those cases were nearly as high profile as the ObamaCare or Arizona cases, but yet they were important enough that they made it all the way to the nation’s highest court and, in several of them, the majority-minority breakdown defied any ideological breakdown that you could conceive of. Scalia and Kagan ended up on the same side of one case, while Kagan and Sotomayor, and Scalia and Alito, ended up on the opposite side of another. Yes, perhaps it’s true that in the highly-charged ideological cases it’s much easier to pick sides, that’s certainly true of the ObamaCare case for example, but that’s not true of every case the Court hears and to judge the entire institution of the Supreme Court of the United States by the relatively small number of highly-charged cases it hears strikes me as being something of a mistake.

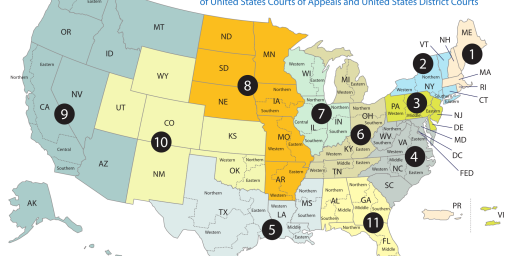

Turley is right about one point at least. There’s nothing magical or Constitutionally required about a Supreme Court made up of nine Justices. The Constitution created a Supreme Court, but left it up to Congress to decide how big the Court should be. Originally, Congress authorized six Supreme Court Justices to correspond to the number of Judicial Circuits it had created. Over time, that number expanded to seven, nine, and ten, shrunk the number back to seven after the Civil War, then re-expanded it to nine in 1869 and that is where the number has stayed despite the fact that the number of Federal Circuits now stands at eleven. Therefore, the size of the Supreme Court has been a variable thing, although it has been consistent for the last 143 years.

However, one has to wonder about the central premise of Turley’s argument. Would a larger Supreme Court really be better? Turley believes so, although I think his arguments, which he fleshes out in an extended version of his WaPo column on his personal blog, are rather unconvincing:

While the best number is debatable, I believe a 19-member court would be ideal — roughly the average size of a Circuit court. Appellate circuits are often divided between liberal and conservative judges. Yet, it is rare that one or two of those judges are consistently the swing votes on all issues when they sit “en banc” or as a whole. While appellate court generally sit in three judge panels, they sit as an en banc court in cases of great significance — the highest level of appeal short of the Supreme Court itself. In such cases, they function well as a whole and show greater diversity of opinion and experience. More importantly, the power of the judges themselves is diluted by the number. Experience has shown that a 19 member court is small enough to be manageable and would not present a significant burden in terms of confirmations.

Turley’s invocation of the Circuit Courts of Appeal confuses the matter quite a bit because, of course, those Courts do not normally operate as an entire panel and instead hear cases in randomly drawn panels of three, with parties to the appeal having the right to seek review en banc on a discretionary basis. That is not the manner in which our Supreme Court operates and, unless Turley is proposing a system under which the Supreme Court sits in panels instead of as an entire body, it strikes me that the idea of a nineteen member appellate court would prove to be unwieldy. Indeed, having argued before the seven-member Virginia Supreme Court, the idea of arguing before a nineteen member panel of the most learned judges in the country would be rather intimidating. Leaving that aside, though, I don’t see how such a large panel of Justices wouldn’t cause the entire Supreme Court appeals process to become an even slower process than it already is. The prospect of forging agreement among nine Justices is one thing, trying to do the same thing among a panel of nineteen Justices? We’d be lucky to get the ObamaCare opinion in August under those circumstances.

Turley points to the fact that the Supreme Courts in other nations are larger than ours, but of course that is an invalid comparison. Comparing one legal system to another is always a mistake to begin with and the role of the Supreme Court of the United States is far different than, for example, the role of the Supreme Courts of Germany, Japan, The United Kingdom, or Israel. So, comparing the size of their Supreme Courts to ours doesn’t necessarily strike me as being valid.

Professor Turley does make one interesting suggestion that, at least as an attorney, I find interesting and perhaps worthwhile:

The expansion of the Court might also allow Congress to force justices to return to the worthwhile practice of sitting on lower courts for periods of time. One of the greatest complaints heard from lawyers and judges alike is that justices are out-of-touch with the reality of legal practice and judging. A 19-member court would allow two members to sit on an appellate court each year by designation – actually forced to apply the rulings that the Court sends down to lower courts. Every five years, justices would be expected to sit as trial or appellate judges. The remaining 17 justices would sit each year to rule on cases.

Even without the expansion plan that Turley proposes, this is an idea worth considering. There was a time, up until about the beginning of the 20th Century, when Supreme Court Justices regularly heard cases in lower courts in the circuits to which they were assigned. This custom is still somewhat recognized today by the practice of each individual justice being assigned to hear emergency appeals from specific judicial circuits, with the most junior Justice typically being responsible for two Circuits to make up for the difference between nine Justices and eleven Circuits. There’s no reason why Justices couldn’t be sent to “ride the Circuit,” as the practice was called, like the used to in the past, although admittedly it would probably be more practical for this to work if there well eleven Justices instead of nine. In any case, there is some value in the idea of Supreme Court Justices being required to sit in on cases where the consequences of their rulings are applied on a regular basis.

Turley makes other recommendations in his expanded version of the Op-Ed. He suggests that Congress require that Congress make the Federal Code of Judicial Ethics applicable to the Supreme Court. At least in the abstract, this is a good idea but it leaves unanswered the question of who enforces the ethics code on the Supreme Court Justices is a question that needs to be answered. He also suggests that Congress require the Supreme Court to televise its hearings. Off the bat, I’m not even sure that this would be Constitutional. Could Congress require that the President televise his Cabinet Meetings or Oval Office conferences? There are several Federal Circuit Courts of Appeal who have made the decision, on a permanent or ad hoc basis, to allow video to be taken of their hearings, but that has been their choice. Given our Constitutional structure, I am not at all sure that it would be proper for Congress (and presumably the President) to force the Supreme Court to televise its hearings, and I’m not at all sure it would be a good idea if they did.

There are, perhaps, several things about the Supreme Court that one could complain about, and Turley does touch on some of them. However, he makes a completely unconvincing case for the argument that increasing the size of the body would either solve those problems or prevent the creation of others. We’ve gone a century an a half with a Supreme Court made up of nine members, and for the most part it has worked out pretty well. Absent some evidence of egregious problems, I don’t see any reasons to change things in the manner Turley is suggesting.

![What happens when you lose [Insert Name]?](https://otb.cachefly.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Screen-Shot-2023-06-11-at-9.39.45-AM-512x256.png)

Did Turley recently suffer a traumatic brain injury? Hell, even by law professor standards that was a loopy rant.

Unless there is a change to the Senate or the Senate rules I don’t think there is one chance in hell that 10 more judges could be appointed to the SCOTUS. I’m not sure there will ever be another judge appointed.

I believe the Golden Gate Bridge District Board has 23 members – I’d say that that’s about 23 too many.

Seriously, given today’s politics, would we really want a few more justices like Clarence Thomas on the Court?

Pleas like this pretty much always boil down to: The Court doesn’t rule the way I like; maybe if we water it down some, maybe its rulings will be more to my taste.

No thanks.

His central premise is essentially correct, the current court is not basing its decisions on sound legal positions and is becoming way too politicized. Furthremore, a 19 man court would not allow one President to drastically change the balance of power in the US as whoever wins this election is poised to do. The Supreme Court jumped the shark in Bush V Gore and has continued to do so with a series of egregious rulings.; You have one judge who by all rights does not do the hard work on cases ( Clarence Thomas) and is quite guilty of a serious conflict of interest on the ACA. ( His wife either has no business shilling for conservative interests or he should have recused himself); Meanwhile on party’s representatives in the Senate abuse procedural rules to an extent never previously seen to block legislation — and appointments, especially to the courts.

Regardless of whether you like the solution-the Roberts court is an abomination. And the best we can hope for now is for Roberts, Alito, Scalia and Thomas to all be in the same car when it goes over a cliff.

How is 19 a magic number? A better number than 9? Why not 100? Why not abolish the Supreme Court entirely?

@Skippy-san: The best you can hope for is some serious mental health treatment. You may not like the courts decisions but if you think the best thing is for the death of the members you’ve got a lot more problems than that.

And being ignored is this: whoever is President when the extra 10 justices get appointed gets to “pack the court”. Convenient, yes?

It is an interesting thought exercise, if nothing else. I do like the fact that a single president would have less of an opportunity to have a significant impact on the makeup of the court.

And, to answer the “court-packing” problem–this could be solved by gradually increasing the number of justices on a set schedule. If the number were to go to 11 (I love a good Spinal Tap reference), Congress could set out a 1 in 4 years, the second in 8, etc. The president may or may not be of the same party, and the timing could be set so that it would start after a president’s first four-year term, so that even if a president is reelected, he (or she?) wouldn’t have the opportunity to appoint both “new” justices.

I’m not sure it’s necessary, but it is interesting to examine.