‘Justice’ Difficult in Chauvin Trial

A criminal trial is a poor venue for solving society's problems.

That Derek Chauvin is being tried on murder charges stemming from the death of George Floyd is itself a rarity. Despite gruesome video evidence, convicting him won’t be easy. And, no, irresponsible claims by congresswomen notwithstanding, that’s not necessarily a miscarriage of justice.

As WaPo’s Mark Berman reminds us, “When police kill people, they are rarely prosecuted and hard to convict.”

Between 2005 and 2015, more than 1,400 officers were arrested for a violence-related crime committed on duty, according to data tracked by Philip M. Stinson, a criminologist at Bowling Green State University. In 187 of those cases, victims were fatally injured in shootings or from other causes. The officers charged represent a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of police officers working for about 18,000 departments nationwide.

Police charged with committing violent crimes while on duty were convicted more than half the time during that period. In the most serious cases — those involving murder or manslaughter — the conviction rate was lower, hovering around 50 percent.

So, that’s actually better than I would have guessed. But my strong guess is that it’s a matter of selection effects. That is, prosecutors are far, far more reluctant (for a whole variety of reasons) to charge a police officer to begin with and likely do so only when they believe a conviction to be a slam-dunk (or the public pressure to do so is intense).

Chauvin’s case is different from many of the most high-profile police prosecutions in recent memory, in part because it centers on an officer who never fired his gun, experts say.

There are a few reasons it is hard to convict a police officer, according to legal experts and attorneys who have worked on such trials: Police have considerable leeway to use force, can cite their training and are typically trusted by juries and judges.

“The law favors the police, the law as it exists,” said David Harris, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh and an expert in policing.

“Most people, I think, believe that it’s a slam dunk,” Harris said of the case against Chauvin. But he said, “the reality of the law and the legal system is, it’s just not.”

In the American system, defendants are presumed innocent, with the state required to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. If even one of the dozen jurors believes the state has not met that burden, there is no conviction. And the burden is higher still for a police officer acting in the performance of his duties. While it might logically seem otherwise, since they’re ostensibly trained professionals, they have much more authority to use force than an ordinary citizen.

A key element that experts say factors into many of the cases is the Supreme Court’s 1989 Graham v. Connor decision, which found that an officer’s actions must be judged against what a reasonable officer would do in the same situation.

“A police officer can use force, but it has to be justifiable,” Bruntrager said. “And what the Supreme Court has told us is we have to see it through the eyes of the police.”

Police shoot and kill about 1,000 people a year, according to The Washington Post’s database tracking such cases. Most of these people are armed and most of the shootings are deemed justified.

Now, counterintuitively, the fact that this was not a shooting actually hurts Chauvin’s defense:

Chauvin’s case is unlike thosein key ways, experts say. “It’ll be much harder … for Mr. Chauvin to claim the usual justification of self-defense than it is when there are shooting deaths,” said Kate Levine, a professor at Cardozo Law. “It’s very hard for him to say, ‘I was in fear for my life when I knelt on this man’s neck.'”

When police shoot and kill someone, the officers’ descriptions of what they saw and felt — and accounts of the danger facing them or someone else — can be a major part of the defense, experts say.

“In many of the shooting cases, the officer will say, ‘I perceived a threat in the form of reaching for a gun, or an aggressive move towards me,’ ” said Rachel Harmon, a law professor at the University of Virginia. “It is difficult for the state to disprove the perception of that threat.”

In this case, Harmon said, “there’s not the same kind of ability to claim a perception of a threat.”

Also counterintuitively, though, there’s a good case to be made that Chauvin’s actions weren’t even the cause of death:

Chauvin’s attorney argued in his opening statement that the officers charged in Floyd’s death felt the “growing crowd” at the scene was threatening. But Chauvin’s core defense, as presented in legal filings and his attorney’s remarks in court, appears focused on something else: making a case that he didn’t actually kill Floyd.

In court filings, Chauvin’s attorneys pointed to Floyd’s health issues and said he “most likely died from an opioid overdose,” trying to break the chain of causation between Chauvin’s knee and Floyd’s death. Medical experts have said say they disagree with the defense’s argument.

But medical experts aren’t on the jury. Jurors might find it quite plausible that Floyd’s use of illegal drugs contributed to his death, in which case Chauvin isn’t guilty of murder. A Financial Times report (“Derek Chauvin trial: the ‘clear challenges’ prosecutors face in police cases“) reinforces this point:

The Hennepin County Medical Examiner’s autopsy last year put the cause of Floyd’s death as “cardiopulmonary arrest complicating law enforcement subdual, restraint and neck compression” and found evidence of fentanyl and methamphetamine in his body. An independent autopsy commissioned by Floyd’s family cited the cause of death as asphyxiation.

Judge Peter Cahill also has allowed Chauvin’s defence team to tell the jury about some parts of a May 6 2019 traffic stop, where there was evidence Floyd swallowed drugs after police approached him.

That said, the thing that has always helped police officers in these cases—the presumption that they’re the good guys, a thin blue line protecting society from evil—may well have changed partially because of the notoriety of this case. Back to Berman/WaPo:

Juries have typically been inclined to trust officers, who come to court with no criminal record and experience testifying, experts and attorneys said. But, they said, recent years might have chipped away at that, due to repeated viral videos of police shootings and other uses of force.

The wave of protests that followed Floyd’s death last year was accompanied by a decline in public approval of police, and last fall voters in several places approved more scrutiny and oversight for police in their communities.

Oddly, as the FT report notes, public attitudes on this case have changed in Chauvin’s favor:

Public polling has suggested that there are deep divisions over how Floyd’s death is perceived, and how those views have evolved since last summer. A USAToday/Ipsos poll last June showed 60 per cent of Americans viewed Floyd’s death as murder, but that fell to just 36 per cent earlier this month. Divisions along racial lines were stark: 64 per cent of black respondents thought it was murder, versus just 28 per cent of whites, who were more likely than blacks to see Chauvin’s actions as negligence.

I’m actually puzzled by the trend. The racial disparity doesn’t shock me but the radical decline in those who believe the actions constitute murder does. Granting that I’ve not paid as much attention to the case per se as the larger movement and social context, I’m not aware of any major new evidence that helps Chauvin. One might think that the violence associated with the Black Lives Matter protests has backfired, as I feared it might. But support for the movement was at its highest last June, when the protests were at their apex, and has waned since.

An interview with Berkley law professor Jonathan Simon (“Despite damning video, complex legal issues make Chauvin trial unpredictable“) conducted just before the start of the trial reinforces some of these points. Indeed, he believed acquittal was the most likely outcome.

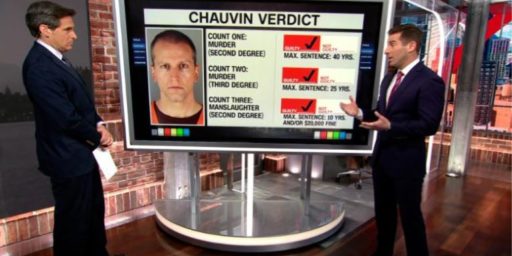

The most serious charge, second-degree murder, requires showing the death was caused during another felony — here, assault in the third degree. The prosecution is also arguing for third-degree murder, which means causing the death in the course of conduct that poses an extreme risk to human life and in an unlawful manner, such as to exhibit indifference to human life.

Finally, the least serious charge is second-degree manslaughter, which is causing the death in the course of doing something unreasonably dangerous to the lives of other people. It usually has to be with a degree of negligence or carelessness, of ignoring potential danger, whether you saw the danger or not.

The elements are difficult to prove, especially in the case of a sworn officer authorized to use force to subdue an uncooperative suspect.

The problem is we’ve got this whole legal focus now in these cases that give the police a kind of epistemological advantage. The fact-finder, the jury, has to put themselves in the position of a reasonable police officer in that situation. And that immediately brings to bear, for instance, how are the police trained to deal with resistant arrestees in this position?

This kind of knee-on-neck hold is obviously permitted in some situations, and that’s going to be focused on. So there is arguably a point at which Chauvin went beyond what the training advised. Maybe after five minutes, with George Floyd’s resistance quieting, Chauvin should have understood that he was no longer sanctioned by the rules and the training to continue using that hold.

And from then on, it’s showing that he’s indifferent to human life. But how many minutes have to go by to prove that? It’s not nine anymore. It’s like four to five, maybe three.

So I think that’s where it’s going to get down into the kind of nitty-gritty, which makes it easier to raise reasonable doubt. Again, you don’t have to believe that the person is innocent. The question is whether you think there’s no reasonable basis on which he could be innocent or on which he could not be responsible.

Simon makes an important larger point that gets to part of what I was driving at in my post chiding Omar’s comments:

But it’s a risk of putting too much emphasis on criminal prosecution as the right way to respond to this obvious assault on the human dignity of Black citizens, especially, and all Americans.

[…]

It’s interesting that this prosecution has been conducted by the attorney general of Minnesota, Keith Ellison, not by a typical local prosecutor. He’s obviously a more political person.

One of the things I think we’re going to see here — I would hope and expect it — is a fair amount of public communication about the nature of these charges and helping the public understand how demanding criminal law is, especially for these kinds of unintended killing theories, so that people will kind of appreciate what “beyond a reasonable doubt” means.

I’ve always thought cases like the O.J. Simpson murder trial [the former NFL player, broadcaster and actor was tried and found not guilty of the 1994 murder of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ron Goldman] are good examples of where public ignorance about what a jury is actually asked to do — not just asking whether they think the person did it, but whether they think there’s a reasonable chance that they didn’t — really doesn’t sink in very much.

Simon also believes that, if Chauvin is convicted, the fact that the city settled its civil suit with Floyd’s family for a whopping $27 million on the eve of jury selection will provide strong grounds for appeal—as it will reasonably perceived as an admission of wrongdoing.

In an ideal world, this trial would not be taking place in such a politically charged atmosphere. We’ve instead had nearly a year of protests, many of them violent, with George Floyd as a primary focus. So, the jury is under rather considerable pressure to convict, with rioting as a quite likely outcome in the event they don’t believe the prosecution proved their case beyond reasonable doubt. And, effectively, Omar was egging them on.

I’m not sure stating the obvious counts as egging them on.

I live in CT, and I don’t need Omar to tell me that….of course it is.

It would be odd if it weren’t.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl: I think it’s perfectly reasonable to declare that “the community is on edge” over the trial. But to imply that an acquittal or hung jury would be “justice not delivered” highly problematic.

Similarly, “It’s been really horrendous to watch the defense put George Floyd on trial instead of the former police officer who’s charged with his murder” delegitimizes a perfectly reasonable defense strategy. Of course Chauvin’s lawyers are going to note that Floyd was a known criminal who has resisted arrest in the past and was high on drugs. It would be malfeasance not to.

Chauvin’s actions would have been inexcusable even if Floyd survived. The sheer amount of time he spent placing his whole weight on someone’s neck and actively prevented multiple medical individuals from intervening to care for the victim’s health indicate this went beyond “procedure”. He cannot claim “fear for his life” since Floyd was clearly unconscious and no harm. There was no legit reason to what he was doing and his BS reason didn’t fly with anyone present either; it was intentional, harmful and without merit as he was repeatedly informed by authorities and others he was acting in a fatal manner.

The only way he gets off is because the defense manages to lie enough that the jury feels comfortable in letting this clear crime go.

Chauvin’s trial alone isn’t going to solve the problem all it’s own. The same will be true if he’s convicted. However, both of them will hopefully mark the start of a trend that will lead to police being held responsible in future cases as well as policing reforms at all levels of government.

If he’s not convicted it will send an unmistakable signal that police can legally murder Black suspects. That’s how Black people will see it and how white cops and their enablers will see it. And the reason they’ll see it that way is because it will be true.

The only reason this is “politically charged” is because of the knowledge this might go unpunished and WHY. In any other functional nation in the world, Chauvin would have been behind bars already and there would be zero quibbling about his clearly documented guilt. This happened in broad daylight in front of dozens of witnesses, many authority figures like cops and EMTs and was recorded from multiple angles to boot. That he might skate – sadly, a good chance – is EXACTLY why the protests happened; the political environment wasn’t “fair” or “just” from the get-go and little has changed.

Chauvin is extremely lucky he’s getting what he’s getting as in most any other nation in the world would have clapped him in irons ages ago. It’s exactly this “charged political environment” that’s getting him the trial that might let him skate on murder and be praised by half the country for it. The jury isn’t under pressure to convict but rather under pressure to come up with a justification to acquit. The normal excuses don’t apply here and the length of time it took removed any sense of urgency or “fear for life”. Chauvin should be thanking his lucky stars for the atmosphere surrounding the trial since it’s pumping up the alt-right and haters to his side when otherwise most reasonable folk would be skeptical of his claims.

Morally the issue is that Chauvin could easily have saved Mr. Floyd’s life at any time by simply easing off for a moment. Worse yet, there were other officers and many bystanders urging him to do so, and willing to help out. He ignored all that.

Legally it comes down to the law, naturally, and to the jury. But there is no doubt, never mind any reasonable doubt, that Chauvin killed Mr. Floyd either out of malice or indifference.

@Michael Reynolds:

They also seem to be able to murder white suspects, even execution style — like for instance a guy crawling down a hallway begging for his life.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/arizona-police-shooting-killed-man-crawling-floor-killed-a8100326.html

The only people who don’t seem to get this treatment are rich people — when was the last time a billionaire was shot for “resisting arrest”?

@Michael Reynolds:

Given the multitude of factors at play in this scenario, the distributed responsibility for negligence (which will continue to be, and as James noted, should continue to be pressed in defense) and the fact that it will only require a single juror (you should definitely acquaint yourself with the demographic and professional info of the individuals serving on this particular jury …) voting no to derail conviction, I think you should probably prepare yourself for the likelihood of an acquittal. There will certainly be an appeal regardless of the outcome, of course, but IMLO it is far more likely that he’s acquitted than not. If I were betting,

I think you’re probably correct in that some aspects of Chauvin’s trial are unfair. AND, I think this is a taste of what black defendants, among others, face on a day-to-day basis. Some websites feature photographs of black people committing violence every day. We see video of it far more frequently than of white people committing violence, even though in absolute terms, white people commit more acts of violence. That stuff is prejudicial too.

Now, I know you don’t want that. I’m not arguing that. I’m wondering how to talk about any of this, frankly. I don’t believe two wrongs make a right. I want to fix THAT without breaking THIS.

James, I sincerely hope that what you meant to say was “that’s not necessarily an incorrect application of current law and precedent”. We all know that HL92 is right about the odds. But “miscarriage of justice” means something entirely different, unrelated to current law and precedent. Justice =/= the law, which is the entire problem.

If you can watch the Floyd video from beginning to end and still not be certain that acquittal would be a miscarriage of justice, you are clearly part of the problem.

@HarvardLaw92:

A hung jury seems a possible outcome, is that an acquittal?

@KM:

Chauvin does have a plausible case for stupidity to make. He’s in deep doo doo for tax evasion, and the way he did it was the dumbest way possible. IMO the jury could be convinced he was unaware Floyd was in distress. Not sure if that would be murder 2 or murder 3. His status as officer of the law, someone who is paid to know better, should affect that determination.

@DrDaveT:

I haven’t followed the trial closely enough to know whether the state is meeting its burden of proof of second-degree murder. In the context of a criminal trial, the only “justice” that matters is that question.

In the larger social context, it was clearly unjust that George Floyd was killed and just that Derek Chauvin was fired from the Police Department for his actions.

Just a little, tiny bit off topic but I have to point out that Rep Omar is just a piker when it comes to interfering in a trial. I remember Manson holding up a copy of the LA Times for the jury to see “Manson Guilty, Nixon Declares”.

Of course, Nixon was the mold from which the modern GQP has been shaped.

@dazedandconfused:

It isn’t an acquittal or a conviction. If a mistral is declared due to a hung jury then there’s either a retrial, a plea deal of some kind, or prosecution decides not to retry the case

@KM:

I’m not sure where this came from. This system, where the police are used primarily to enforce class structure and are free to use violence to do so, is the default around the world. The few places where it is not true tend to be extremely homogenous.

Actually, I take that last part back. I can’t think of anyplace where it isn’t the norm.

@James Joyner:

I fully expect a hung jury…but a reasonable person cannot watch the length of the video and not think Chauvin is guilty. Someone on that Jury will insist on not delivering justice.

James, in the end you use a long list of outrages to ……. justify?

Something?

@dazedandconfused:

It would either be retried, they can convict on a lesser charge, some sort of plea deal might be reached, or the prosecution could simply decide to not continue with further prosecution of the case.

First of all, that jury is not going to acquit him. Secondly, I’d expect a hung jury, except for the fact that nobody in their right mind would ever risk wanting to be known as the person who thought Chauvin wasn’t guilty. The usual cop defense relies on split-second in the moment thinking. Like, the guy was unarmed and reaching for his ID but I thought it was a gun oh boy what an error I made. This is not that. This is a pig kneeling on a guy’s neck for nine minutes while the man cries for his mother and a crowd explains to him that the man is dying.

You can speculate online with glee about reasonable doubt all you want. But if your on that jury and you don’t want to convict your fellow jurors are going to burn you however they can and your identity is going to be figured out. Imagine wanting a google search for your name having the first hit as being the juror who couldn’t convict in this case. It’s you and the Emmett Till jury, side by side forever. Your life would be over, unless you want to end up on Tucker selling your book about how the woke left has ruined your life. So maybe there is an angle, I don’t know.

@dazedandconfused: HL92 said, “…and the fact that it will only require a single juror (you should definitely acquaint yourself with the demographic and professional info of the individuals serving on this particular jury …) voting no to derail conviction.” The one hold out makes the hung jury. As to how acquittal factors in, my guess and IANAL is that the decision not to retry or the change of venue (MPLS will not be able to find another group that don’t already know the trial) to a “back the blue” area will create the environment for a real or de facto acquittal.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

Technically we call it a mistrial, and I don’t mean to assert that it would result in a technical acquittal. It wouldn’t, but in practical terms, the eventual outcome is likely to be equivalent to one, in that, barring a plea bargain, it’s unlikely that this gets tried again in Hennepin County. He’s made the same mistakes (essentially trying the case in the media well before opening argument for political reasons) that Mosby made in the Freddie Gray trials. And those turned out exactly like I predicted they would. I don’t see this being much different. There are at least 4 jurors on that jury I can see voting not to convict, possibly more.

@HarvardLaw92:

A reminder, the Barr, Justice Department refused to preclude the option of a civil rights lawsuit against Chauvin. He is alleged to have offered a guilty plea on a lesser charge, if the JD didn’t prosecute a civil rights case and he served his time in a Fed facility. If Chauvin is found innocent in Mpls, he still will face Federal charges.

@JohnMcC:

Well, maybe the mold for dishonesty, not so much other parts. For instance he seemed to have some understanding of foreign affairs, brining in détente and travelling to China. Who in the modern GOP would have done the equivalent today? I’d have taken Nixon a thousand times over Trump or Cruz.

@HarvardLaw92:

At this juncture my guess is those four jurors can be talked into a murder 3 conviction. The other cop’s and that EMT’s testimony being key.

@Modulo Myself: Y

Which, almost certainly, is going to be the defense’s argument on appeal if there is a conviction.

@HarvardLaw92: @dazedandconfused:

I was wondering about this stacking of charges. I thought the courts had rule against charging lesser-includeds in this manner, precisely because it naturally leads to jurors “meeting in the middle.”

In the Alternate Universe where I’m the single Not Guilty vote, the trial memoir I bring to promote on Tucker is entitled, The Hung Juror.

@James Joyner:

Sure, a video of a cop kneeling on a helpless man’s neck for 9 minutes which everyone in the world has seen tends to cause problems when it comes to a trial.

@James Joyner:

Harvard Law will have to answer what the courts have ruled on for lesser-includeds. However to to me giving this jury the option of deciding whether Chauvin was was trying to harm Floyd and accidentally killed him or was merely being stupid is fitting. The jury has to decide whether or not someone is guilty, so I don’t have a problem with giving them some leeway on what someone is guilty of.

@dazedandconfused:

I have my doubts. They’ve done a very good job of planting the fact that he was high on opiates in the minds of the jury. No matter how many medical experts you haul up there, it will be next to impossible to remove that fact from their minds. It will be the sway point that gives someone disinclined to empathize with Floyd the intellectual out they’ll need to rationalize voting no. The mental argument will go something like “I may not think that the opiates caused his death, but I can’t be sure they didn’t contribute to him dying” and that will be the ballgame. I don’t think it’s right, but I’ve been doing this a long time and I can tell you that jury trials are not about justice in the most direct sense of the word, They’re about blame. George Floyd is dead, and someone has to be blamed for it. The prosecution wants the jury to blame Chauvin, while the defense will give some of them just enough doubt to vote no by serving them up Floyd to blame instead. This is just how criminal trials work.

Most likely outcome, IMO, is a mistrial on the murder charges and a plea bargain for IVM. Even that will depend on how the jury poll goes after the mistrial.

@James Joyner:

No. Minnesota law (631.14) explicitly enables criminal juries to acquit someone of murder and instead choose to, on their own initiative, convict them of manslaughter (in any degree). It’s intended to increase the likelihood that a criminal jury in a murder trial will find the defendant guilty ofsomething rather than effectively letting them walk. They’d have to unanimously agree to acquit on the murder charge, and then unanimously agree to convict for some degree of manslaughter, which can be a tall order, but it has happened.

@Sleeping Dog:

It’s possible, sure. 18 US 242 does have teeth.

I’ve been following the live blog of the trial at The Guardian, text only. The testimony of the Chief of Police seemed quite devastating for Chauvin (fingers crossed). The thing is the blog doesn’t report as much about cross examination by the defense, so I’m not sure how effective it was on the jury.

How do people feel about the live media coverage of trials like these (or any trial for that matter)? I don’t know how I “should” feel about it, but it makes me uneasy……for reasons that are both known and unknown to me.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl:

There is a reason why many folks working in this space prefer the term “Criminal LEGAL System” over other formulations.

So if I hit with my car a guy who has terminal brain cancer with a month to live, I can say the cancer really killed him and not the collusion which crushed his skull?

What were the actuarial chances that had Floyd not run into the police that day, he would have dropped dead of fentanyl abuse and asthma later that night?

So he died of an opioid overdose? How does that square with him walking around and trying to buy stuff at a store at 20:01 (when the clerk called 911), talking coherently to the cops at 20:14 (when he told them he was claustrophobic) and likely dead 26 minutes later at 20:27 (when Chauvin finally took his knee off his neck)?

That’s not a good case for a cop’s knee on his neck for over 9 minutes not being the cause of death; that’s a case that defies common sense.

@Mimai: I am 100% certain that the live media coverage is over-the-top-breathless, and hoping for riots, regardless of the verdict. Despite not having ever watched any.

Such coverage has always made me uneasy. Same with Rodney King, and Princess Diana….

@HarvardLaw92:

Precisely.

I don’t know that I find it objectionable in this case, where the lesser-includeds are all consistent with the theory of the case. There have been times where that’s not the situation—where it couldn’t have been involuntary manslaughter under the scenario laid out by prosecutors—where it seems unreasonable to allow it.

@The Q: @rachel: The argument isn’t that he would have died anyway. It’s that, if Chauvin had acted this way and Floyd didn’t have drugs in his system, he wouldn’t have died.

@James Joyner:

Precisely. I’m not necessarily uncomfortable with the concept of a guilty verdict on the 3DM charge (despite the terminology, it’s not really a murder charge, since murder as a concept requires the intent to kill as an essential element). It’s more accurately (and generally used to be termed) negligent homicide, and in my mind that fits the circumstances of the events well enough that it’s the most effective prosecutional path.

That having been said, the opiates do complicate the matter. From the standpoint of a non-empathetic juror, the question isn’t even “if Chauvin had acted this way and Floyd didn’t have drugs in his system, he wouldn’t have died”. It’s “If Chauvin acted thus way and Floyd didn’t have drugs in his system, he might not have died.” That’s all it will take to sway one of them, IMO, and in this scenario, unfortunately one juror is all that’s necessary to derail a verdict.

@HarvardLaw92: Is there a criminal law analog to contributory negligence? Or would uncertainty as to whether Chauvin’s actions killed Floyd simply reduce the crime to something like aggravated assault?

@James Joyner:

I generally think it’s reasonable, to be honest. Imagine a scenario where I’ve caused a death and I’m charged with first degree murder. The law requires that several elements defined in the law be proved beyond a reasonable doubt to sustain convicting me of 1DM. In my trial, the prosecution is well able to prove that I caused the death, but can’t so prove, for example, that I planned it ahead of time (premeditation is a required element of 1DM). Without lesser included offenses being available to the trier of fact (be that a jury or a judge), the choice becomes binary. Either I must be convicted of the charge, or here, because the required elements weren’t satisfied, I must be acquitted. Even though there is ample evidence I caused the death, I’ll walk, and because jeopardy has attached, you can’t even bring me to trial again on a different charge.

In our system, the trier of fact establishes the facts and fits them to the relevant statutes to determine whether the facts fit the elements of those statutory crimes. In the example above, the jury can’t fit me facts to a 1DM because the law hasn’t been satisfied, but I clearly have culpability for causing the death. It’s better that the jury has the option to impose accountability for the elements that could be satisfied than it is for me to just escape that culpability on a technical element.

@James Joyner:

That’s a great theory which deserves to be tested in court.

Just have Chauvin take a drug test to show he’s clean, then have someone press his knee on his neck for 9.5 minutes. if he doesn’t die, he should be acquitted.

@rachel:

“So he died of an opioid overdose? How does that square with him walking around and trying to buy stuff at a store at 20:01 (when the clerk called 911), talking coherently to the cops at 20:14 (when he told them he was claustrophobic) and likely dead 26 minutes later at 20:27 (when Chauvin finally took his knee off his neck)?”

Good Questions! Hopefully the DA will address this in the trial. Fatal opiate overdoses tend to happen very shortly after ingestion. Speaking as someone with a bit of practical experience around illicit drug use, George Floyd did not appear to be suffering a protracted drug overdose. 3.5 minutes with out oxygen to the brain, if I recall correctly, is generally considered the time irreversible brain damage occurs. 5, brain death. This is with healthy people, not under the influence of drugs.

“That’s not a good case for a cop’s knee on his neck for over 9 minutes not being the cause of death; that’s a case that defies common sense.”

The defense is just doing their job by trying to sow reasonable doubt in the minds of the jury.

People that are swayed by pro law enforcement

arguments in this case, seem to be emotionally bought in, and “common sense” doesn’t seem to factor in, unfortunately.

@James Joyner:

No. Contributory negligence is a concept applicable to torts. In criminal law it’s generally not a defense to prosecution that the victim contributed to causing his own death. Where it can have an effect is on raising doubt in the minds of jurors that the elements of the crime have been satisfied. One of the fundamental elements of homicide is that the accused caused the death of the victim. The trier of fact here is a jury, which under Minnesota law must unanimously agree about the determination of fact in order to convict. Defense attorneys will seek to slide that implication in not because it exonerates guilt, but because it creates doubt, and doubt is all that’s required to detail.

I guess the short version to your question is that the law doesn’t consider it to be exculpatory, but a jury does what a jury does. It’s human.

You’d do well to follow attorney, Andrew Branca at Legal Insurrection, who is doing detailed daily synopses of the trial. The defense attorney is ripping apart most of the prosecution’s case in real-time, on cross, before the defense is presented. Even the seemingly determinative video has been challenged on perspective by other videos showing the knee on the shoulder more than the neck. The NY Times, WaPo, CNN, etc. are priming to create riots when/if there is an acquittal.