Maine Joins ‘National Popular Vote’ Compact

A longstanding project inches forward.

AP (“Maine joins compact to elect the president by popular vote but it won’t come into play this November“):

Maine will become the latest to join a multistate effort to elect the president by popular vote with the Democratic governor’s announcement Monday that she’s letting the proposal become law without her signature.

Under the proposed compact, each state would allocate all its electoral votes to whoever wins the national popular vote for president, regardless of how individual states voted in an election.

But the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is on hold for now — and won’t play a role in the upcoming November election.

Gov. Janet Mills said she understands that there are different facets to the debate. Opponents point out that the role of small states like Maine could be diminished if the electoral college ends, while proponents point out that two of the last four presidents have been elected through the electoral college system despite losing the national popular vote.

Without a ranked voting system, Mills said she believes “the person who wins the most votes should become the president. To do otherwise seemingly runs counter to the democratic foundations of our country.”

“Still, recognizing that there is merit to both sides of the argument, and recognizing that this measure has been the subject of public discussion several times before in Maine, I would like this important nationwide debate to continue and so I will allow this bill to become law without my signature,” the governor said in a statement.

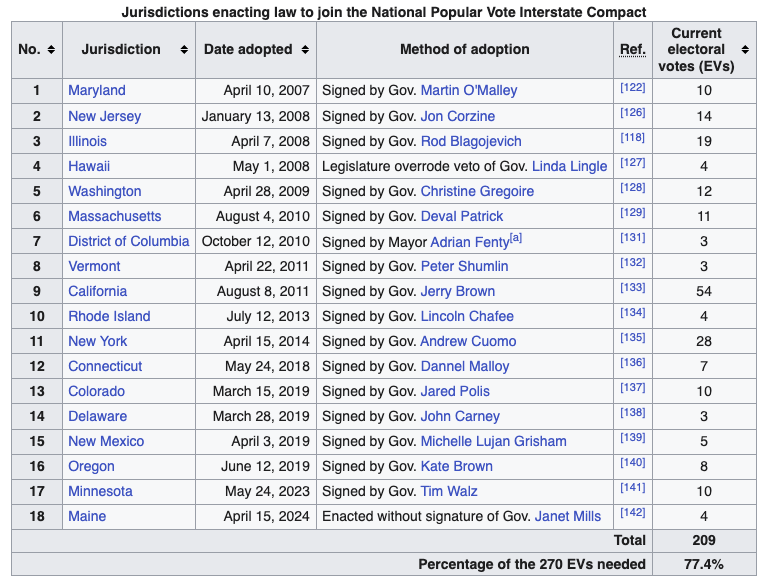

The compact would take effect only if supporters secure pledges of states with at least 270 electoral votes. Sixteen states and Washington, D.C. have joined the compact and Maine’s addition would bring the total to 209, the governor said. Other hurdles include questions of whether congressional approval is necessary to implement the compact.

In Maine, one of only two states to split their electoral votes under the current system, the debate in the Maine Legislature fell along partisan lines with Republican united in opposition.

The project was introduced in 2006 and I wrote the first of many OTB posts on the subject (“Abolishing the Electoral College by Stealth“) on April 22 of that year—almost exactly 18 years ago. It gained its first signatory, Maryland, in April 2007. I wrote about that one (“Maryland Passes ‘National Popular Vote’ Law“), too. There have been a whole passel of OTB posts on the subject since, with Doug Mataconis passionately against, Steven Taylor and I reservedly in favor, and Robert Prather skeptical of its constitutionality.

Steven and I both thought from the beginning that this agreement is likely in accord with the Constitution, as state legislatures have near-plenary power in how they allocate their Electors. Indeed, there’s no requirement to even hold a popular vote. But Doug and Robert are joined by many legal scholars who contend that this amounts to an interstate compact and thus requires Congressional approval. Others argue that, since this effectively eliminates the prospect of the House of Representatives having the power to elect the President in the event of an Electoral College tie, it’s an unconstitutional changing of the federal-state balance. Still others argue that this would violate the 14th Amendment, since some states would have wildly different election laws than others.

With steady progress, we’re getting considerably closer to the 270 Electoral Votes needed to put this to the test. Wikipedia shows how it unfolded:

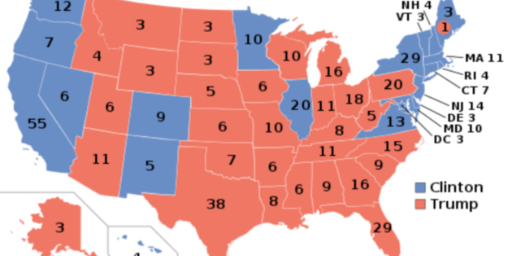

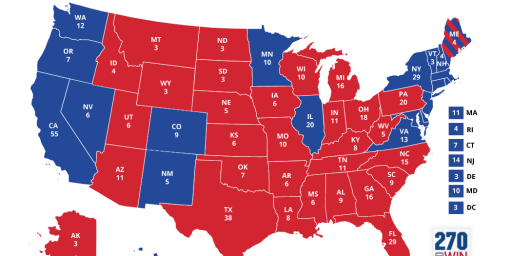

It’s noteworthy that the 17 states and the District of Columbia that are on board are all solidly Democratic. That’s not surprising, in that the current construct considerably advantages Republicans, as seen most vividly with the 2000 and 2016 elections.* Not only would NPV change the rules in their favor but there’s very little downside risk for them: if the Republican candidate won the popular vote, it’s a near-guarantee they’d win the electoral vote, too.

It’s highly unlikely, then, that Texas and Florida, our second and third most populous states, with 40 and 30 Electors, respectively, will join. The current rules advantage the party that their constituents tend to prefer.

Pennsylvania, with 19 Electors, is the next biggest prize. They tend to be in the Blue column but are a swing state and get outsized attention from candidates under the current system. They’re unlikely to join.

Ditto Ohio (17), Georgia (16), North Carolina (16). They’re all swing states at this point, albeit ones that tend Red.

Michigan, then, is the next biggest gettable prize, with 15 Electors. That would put the total at 224—still 46 short.

Virginia is purple trending blue. It has 13 Electors.

You likely see where this is headed: the number of solid Blue states that haven’t already joined is small and we’d need most of them to sign on as they have a decreasing number of Electors. And, at that point, you run into the question that Maine had: do even Democratic-leaning small states want to give up the disproportionate voting power they have under the existing model?

We’re still a very long way away from 270. At which point we can test it in the courts.

___________

*Indeed, the string goes back to the 1888 and 1876 elections but the parties and electoral configurations were sufficiency different to make them a distractioon.

This statement jumped out at me.

How close is this statement in congruence to the Independent State Legislature Theory?

There was a slight EC advantage for Dems in 2004 and 2012. This fact is a bit arcane given that the EC and popular vote went to the same candidate in those elections, but it suggests that the conventional wisdom that the EC intrinsically advantages Republicans in the 21st century is somewhat of a myth, despite the fact that we haven’t yet had an election where the Dem wins the EC and loses the popular vote.

I do think that when the Compact was founded in 2006, they had the 2004 results in mind, as it depended on Kerry narrowly losing Ohio; if he’d won it, he’d have won the EC without the popular vote, a direct reversal of 2000 in terms of party. I think this suggested to the people who created the Compact that any partisan advantage of the EC was ephemeral, and that therefore they could get both parties on board with the idea. (A while back I watched a lengthy interview with a representative for the Compact, and the guy was a Republican.) The original theory behind building up support for the Compact was that states that are solidly red or solidly blue stood to benefit the most from a shift to popular vote, whereas swing states had the most to lose.

Unfortunately, 2016 and even 2020 (where Biden won both the EC and PV but where it was obvious Trump was closer to winning the EC than the PV) have cemented the partisan divide on the issue. Partly it’s because of how it impacts the legitimacy of the two most recent Republican presidents (it would force them to admit that no Republican has reached the White House by popular mandate since hair metal), which has led Republicans to dig in their heels. That’s the most charitable interpretation. The larger truth is that, even before Trump, Republicans have increasingly adopted an anti-majoritarian worldview in which they not only look suspiciously on any attempt to make the electoral system fairer and more representative, but actively work against that goal.

So if Virginia were to take it up and pass it by 2028, that would make the count 33 short.

Nevada has actually passed it out of both houses, but since it amends the Nevada Constitution it also has to be re-passed by the 2025 legislature and then go through a statewide vote in 2026. Still, it’s cleared some significant hurdles and is on a good path forward. Their 6 EV’s would cut the gap to 27.

Wisconsin will soon be operating under brand new maps, much friendlier to the state’s Democratic majority. And Dems there would have a lot of incentive to push forward with this. Getting the cheese state would cut the gap to just 17.

It has passed the AZ lower house in previous sessions. I wonder how this abortion ban debacle will impact the AZ house and senate races, where each is held by a 2-seat Republican majority? Their 11 EV’s would bring the gap down to just 6.

Those final 6 are quite the road block. New Hampshire, maybe? Only 4 EV’s, still 2 short. We come back to the red swing-ish states of NC and GA (OH is trending in the wrong direction, I think). I don’t see either of those two states having unified Dem control in the next 4 years.

@Kylopod:

I don’t think anyone serious is arguing that the advantage is intrinsic, which I am reading as “naturally” and “now and forever.” However, given population sorting and the organic way that states and state boundaries evolved–not to mention population densities or lack there of–the nature of the electoral college is that it’s going to almost always favor one party or the other. And that favoritism is slow in shifting.

And moving towards a system that isn’t subject to this particular sort of bias* and where every vote counts the same is better than what we currently have.

Today it favors Republicans. Tomorrow it may favor Democrats. All of this is also further complicated by each State’s electoral rules (for example, the role that Felony Disenfranchisement plays in making sure that significant portions of certain sections of the population cannot vote in certain states).

My take is that any movement towards a national popular vote is good for the country, and this is, unfortunately, a generational issue given the construction of our Constitution. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do it. It’s just that given that we’re two centuries into the electoral college, expecting it to be undone quickly is unrealistic. I jsut hope it won’t take us two centuries to reach a more democratic solution.

* – I’m not suggesting a national popular vote wouldn’t have it’s own biases. I do think those biases would be more representative of the total population than our current system. And so that’s my preference.

@Scott: It’s related but not the same. There’s no disputing that state legislatures have the bulk of the power over elections under the Constitution. ISLT posits that ordinary checks and balances, like a governor’s signature and state courts affirming that the law doesn’t violate the state or US Constitution, somehow don’t apply. That’s just a weird notion.

@Neil Hudelson:

If the gap were to be cut to just 2 EV’s, the results of the 2030 census could have a profound impact and immediate impact on our nation. (Although the most populace blue states–IL, CA, NY–are all losing population, so probably not.)

@Matt Bernius:

That is what I’m disputing, for the reasons I outlined. The EC favored the Republicans in 2000, 2016, and 2020 but favored the Dems in 2004, 2008, and 2012. The effect is not gradual but ephemeral.

@Kylopod:

Some more details on what you are basing that assessment on would be helpful for this conversation.

@Matt Bernius: Even in an election where the EC and the PV are won by the same candidate, it is still possible to discern which candidate has the EC advantage–which I’m defining here as being closer than the other candidate to a scenario of winning the EC while losing the PV. The most intuitive recent example is 2020, where Biden won the PV by nearly 5 points but where his EC victory depended on wins of less than 1 percent in three states.

In 2004, 2008, and 2012, Dems showed an EC advantage for similar reasons. In the two Obama elections, the reasons are arcane and I don’t wish to dwell on them (basically Obama won the tipping-point state of Colorado by a wider margin than his national lead), but 2004 is pretty intuitive, for the reasons I explained earlier.

@Neil Hudelson:

Given the water and heat problems in the American South, how long will that remain true? My wife and are starting to look at where we want to retire in the Northeast and believe me, we are not the only ones moving back north! Housing prices are flying up!

@Neil Hudelson: At least for NY, it’s not clear that’s true; the reason NY lost an elector was because other states are growing in population, while NY’s population has been flat.

And, as @MarkedMan said, based on housing prices/availability, there’s much more demand for housing than there is space. Even the upstate cities/towns are gentrifying.

@Kylopod: Thanks, I was wondering if that was the case based on your previous post. I need to think about that mode of analysis a bit before I can comment.

Something about it isn’t landing with me, but I can’t articulate why at the moment. Which could also be an example that I am wrong.

I’d definitely be interested in James and Steven’s take on that analysis from a Poli Sci POV.

Tested in the court…. as well as the accountability the state legislatures have to face up to when this is forced on the voters by surprise. Anyone really believe the average voter has paid attention to what these agreements will do?

Or, what happens when Trump sweeps the popular vote in November. Suddenly, reality will bite. You’ll say Trump can’t win the popular vote, but can’t he?

I would suspect that if this gambit is ever played and usurps the voters of a state, the state politicians are going to immediately be fighting to save themselves from an angry electorate.

What happens when farting starts to make us all float like those sodas do in Willy Wonka? What happens when iguanas develop the power of friendship? What happens when my left pinky toe develops sentience and wants to pursue a career?

These are all great questions.

The primary reason for the EC imbalance is that the House has not grown in over a century. Increasing the size of the House results in more EC votes, greater fidelity for those votes, dilution of the EC votes for the two EC votes for Senate seats, and a much stronger and closer alignment of the EC with the PV.

Increasing the size of the House would raise zero constitutional issues, and you would not have to worry that some state will decide to remove itself from the Compact when it’s forced to allocate its electors for a President its population didn’t want and didn’t vote for.

I’ll be interested to see if the SCOTUS holds that it’s the type of interstate compact that has to be approved by Congress, and if so whether Congress will approve it.

One point of clarification: All the states to join the Compact so far are states that had a Democratic trifecta at the time of passage (and only one them, Vermont, no longer has that trifecta, by virtue of its currently having the only sitting Republican governor in the nation to endorse Biden in 2020). Michigan is the only Democratic trifecta state left.