Most Politics Is National

Tip O'Neil's famous saying hasn't been true in a long, long time.

Veteran journalist Jeff Greenfield looks at the Virginia governor’s race, which he calls the “starting gun” for the 2022 election cycle, and proclaims, “Virginia Buries an Enduring Political Myth.”

We don’t need to wait until the results are in, however, to draw one clear conclusion from this contest. Itwill or should deal another decisive blow to one of the most enduring, least useful observations about American elections: “All politics is local.”

That piece of political wisdom was popularized by Tip O’Neill, the late speaker of the House. It was the title of the Massachusetts Democrat’s 1995 memoir, and it conveys the sense of folk wisdom rooted in the realities of neighborhoods, grocery stores and churches, far from the ivory towers of academia. Voters make judgments, the adage teaches, on matters rooted in their daily lives — the safety of their streets, the quality of their kids’ schools, the ability of their elected leaders to respond to their needs.

O’Neill himself explained his approach this way: “You can’t assume anything in politics. That’s why every Saturday I walk around my district. I talk to the longshoremen in Charlestown. I listen to the people in East Boston and their concern on the airport noise. I walk down to the Star Market in Porter Square, and people tell me about meat prices.”

As a guide to staying in touch with your constituents, this is wise counsel. Politics is filled with examples of powerful officeholders brought down by their failure to keep in touch with the people who elected them. But as a guide to what motivates voters, it has long since ceased being all that useful.

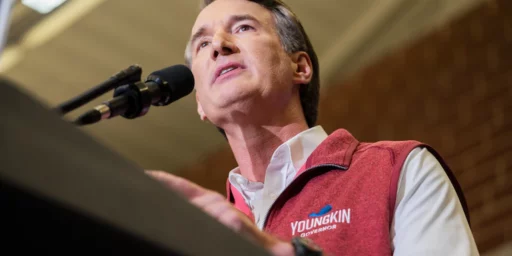

Take the most-watched race of the fall: Virginia, where Democrat Terry McAuliffe and Republican Glenn Youngkin are in a close contest. (You could almost hear Democrats’ heart palpitations after one Fox News poll showed Youngkin up by 8 points among likely voters, followed soon after by a Washington Post poll with McAuliffe ahead by 1). But to some extent, the candidates are a sideshow: The outcome is far more likely to hinge on Joe Biden and Donald Trump — and whether the president or ex-president proves to be a bigger anchor on his party.

If this “nationalization” seems like something new, it shouldn’t. It’s been a growing fact of our political life for decades.

Presidential elections have almost always been driven by broader factors than local matters: war, inflation, recession, domestic upheaval, corruption. Over the last decade or two, the drift — more like a surge — toward political polarization has seen the steady disappearance of split ticket voting, where a personally admirable candidate of one party could win the votes from those who identify with another party. In 2020, only one Senate candidate, Maine Republican Susan Collins, won in a state carried by the other party’s presidential nominee. A decade ago, 23 senators came from states that had voted for the other party’s presidential candidate. Today, the number is six.

Greenfield is right that our politics have been increasingly nationalized. As I’ve been telling students for decades now, despite the mythology of schoolboy civics—that politics should be conducted at the local level because proximity means familiarity—the fact of the matter is that the media environment has long made the reverse true. Most people can’t name their local councilman or state delegate but everyone not only knows who the President of the United States is and the name of his wife and probably even his pets.

Still, the alignment of Presidential and Senate voting is a function of a near-complete sorting of the parties that has been gradually taking place over four decades. The Susan Collinses and Joe Manchins of the world are simply curiosities at this point whereas they were fairly commonplace twenty, let alone forty, years ago.

But does the pull of national issues really play out in an off-year gubernatorial race? Isn’t education, for example, one of Youngkin’s major themes?

It is, but that only strengthens the case. Virginia’s school boards are political hotbeds this year, but not because of funding arguments or normal education debates: It’s because of a national culture war over how we teach history and social studies, inserting itself angrily into a level of politics that used to be the most local imaginable. The pushback of suburban parents in a Democratic stronghold like Loudoun County, Virginia is itself part of a national revolt over a series of issues that encompass resistance to “top-down” commands: from masks to vaccines to what children should be taught about race.

However, the specter of last year’s presidential campaign is what hangs most heavily over the Old Dominion. Biden’s sagging approval ratings have fueled deep concern among Democrats that their voters, either out of weariness with last year’s battle or disaffection with Biden’s performance, may lack the enthusiasm to vote. The urgency with which Democrats were pushing for passage of Biden’s legislative agenda demonstrates the belief — wholly accurate or not — that the success on Capitol Hill could trigger a late burst of enthusiasm among Virginia Democrats.

And then there’s Trump. All through the campaign, McAuliffe has been making the 45th president his key issue.Ifyou vote Republican, he argues, you will be giving new energy to Trump and Trumpism. Biden and Barack Obama did the same in their campaign swings with McAuliffe. The Democratic Party has done everything to beckon Trump into Virginia except chartering a plane for him. Just as consistently, Youngkin has been saying nothing to alienate Trump’s supporters, while saying nothing to imply he is a full-blown MAGA Republican.

“Trump?” Youngkin has more or less been saying. “The name is vaguely familiar, but…”

It’s a delicate dance for Youngkin, but if he succeeds, it could offer a path for Republicans seeking to win back the independents and suburbanites the party hemorrhaged during the Trump era.

Honestly, I think this assumes that people are paying way more attention to the campaign than they actually are. Youngkin is indeed trying to have it both ways, sending sops to Trumpkins that he sympathizes with their sentiments while also signaling that he’s not a racist troglodyte.

But I think the race is as much a referendum on Biden as it is Trump. McAuliffe, a thoroughly unexciting candidate who won his party’s nomination for another go at the state house by default, is doing everything in his power to paint Youngkin as Trump 2.0 but, because he’s not Trump—and Trump isn’t in the White House anymore—it’s a hard sell. And there’s simply a voter enthusiasm gap, with Democrats neither motivated by ousting Trump nor excited about the seemingly never-ending internecine fight over the budget whereas Republicans still see themselves as put upon.

I don’t have a strong sense of how the race will turn out. The polling is all over the place and, as I’ve noted before, some 900,000 Virginians voted early, so any late swings will be muted. I’ll vote, as is my custom, on Election Day tomorrow and do so, with very little enthusiasm indeed, for McAuliffe.

But I don’t know that it portends much for 2022. Barring major developments, I fully expect Republicans to retake the House and Senate, regardless of whether McAuliffe or Youngkin wins. That’s almost always what happens in midterm elections after a new President comes to office and there’s no reason to think Biden will be an outlier. And, unless the GOP primary electorate comes to its senses and nominates a sensible candidate like Larry Hogan for President—which they almost surely won’t—Biden, Kamala Harris, or some other Democrat will almost surely carry Virginia in 2024..

First, without a doubt, our politics (and parties) are highly nationalized (I think even when O’Neil quipped his famous quip, we had pretty nationalized politics at the time).

Second, man, I wish we would stop putting so much meaning into a given mid-term election.

Third, from a democratic theory POV, we would be better off electing every office on the same day as that would mean maximal turnout (which means getting the best reflection of public preferences, which is what representative democracy is supposed to do).

I believe it was the 1994 midterms that was the beginning of the nationalization of politics, though it’s a process that’s been in development up until the present day–with the record-low level of ticket-splitting in 2020 House races being an indicator of that.

It’s not clear at this point whether or how much Trump contributed to it; definitely things are more nationalized now than they were prior to 2016, but it’s possible he was simply the beneficiary of a trend that would have played out even with other Republicans heading the party.

The article quotes Tip O’Neil,

A modern senator probably spends Saturdays on the phone with potential donors.

Politics is personal, individual. 100% of choices are made by individual humans. Groups, parties, nations and epochs may be insane*, but they do not cast ballots.

*That’s right, I’m dropping some Nietzsche.

@Kylopod:

I think social media had a lot to do with this. Before you could only talk politics with your relatives, friends, colleagues, and neighbors. Now you can fight with strangers on the other side of the country. Or the world.

@Steven L. Taylor:

In Virginia, we not only have all state elections in off-off years (coinciding with neither Presidential nor even midterm Congressional elections) but hold our non-presidential party primaries months after the presidential primaries. I haven’t thoroughly investigated the history of this but would be hard-pressed to come up with an explanation other than intentionally depressing turnout so that the “right” people choose the winners.

@Steven L. Taylor:

So this. It seems like every mid-term election is a “rebuke” of whoever is in power and their constant “overreach”–or at least that’s the constant narrative.

Again, 100% to this. I don’t understand why so many municipalities decide to do their elections on another day. From a fiscal responsibility point of view, it makes no sense. My cynical guess is it’s a mix of wanting to maintain a sense of autonomy and suppressing participation.

Tying in with the other post this morning: The loss of local news reporting is a large contributing factor. It used to be that every municipal meeting was reported on and summarized. Now they’re not.

And… I’m guilty of this. Working full time plus writing & editing the paper and doing live stream interviews doesn’t exactly make me relish the though of sitting in the dozen or so committee and council meetings in my area–especially since I’m not being paid for it. 🙂

I actually think a part of the context of O’Neill’s statement that gets lost in the discussion is the impact of the Southern Strategy. Since the 1960s the South started to vote Republican in presidential elections, yet at the state and local level these states remained strongly Democratic. This was in part because the infrastructure of the old Solid South was still in place–it didn’t really start to crumble until (again) 1994. And the politicians in these states, even those who weren’t overtly racist, were able to differentiate themselves from the bums in Washington.

Now, I do think the local aspect to politics predates the Southern Strategy, but the latter was still a big element to the national vs. local dynamic in the 1980s when O’Neill made that remark. And it’s something that maybe politicians didn’t want to say out loud, which is why he felt the need to put it in those romanticized terms.

Third, from a democratic theory POV, we would be better off electing every office on the same day as that would mean maximal turnout (which means getting the best reflection of public preferences, which is what representative democracy is supposed to do).

Do you mean same election cycle? There is some evidence that vote by mail — which by definition means not everyone voting on the same day — produces a modest increase in participation.

Just unofficial observation, but based on living in a western state with a long history of ballot initiatives, nothing drives voter turnout quite like an initiative issue about which people have strong feelings. People seem to like voting on individual issues more than they like voting on individual politicians.

@Michael Cain:

Should have included in my previous comment that eliminating everything but the every-two-years general elections would be a huge spur for getting vote by mail everywhere. If the ballot includes, for example, President, my US Representative, one of my US Senators, Governor, AG, Secretary of State, my statehouse representative and senator, county commissioner(s), county recorder, county sheriff, DA, mayor, city council member(s), university regents, special district commissions and boards, judge retention, and then gets to initiative and referendums… well, anyone with any sense is going to prefer filling out that mess at their kitchen table rather than standing in line waiting for the people ahead of them to make (or even mark from notes) 30 or 40 decisions.

@James Joyner:

This is the likeliest of explanations.

@Michael Cain:

I mean that all offices should be on the same basic calender (and yes, vote by mail appears to increase turnout, but that isn’t my point).

To be direct: we should elect Pres, Gov, Congress, down to local offices on the same day/part of the same cycle.

I also think that Congressional mid-terms (due to the 2-year term) is problematic, both for the above reasons and for others I don’t have time to detail at the moment.

@Michael Cain:

There is something to this, but I would wager that on average turnout for presidential elections is on average higher (likely substantially so) than turnout in off-term ballot initiative/referenda elections (although I am also confident that there are exceptions based on specific issues).

But to James’ point in the OP: we understand, and vote primarily, for President (which would be an okay approach to electoral politics if people were voting for parties to form majorities in parliament, instead of focuses on one office in one branch of a sep of powers system).

Prof. Joyner: I live in Virginia, as well. There seems to be an election every year (I vote in them all). The only thing that has made this iteration funny is that the ‘we pay cash for homes’ folks and the ‘get your medicinal marijuana card’ folks have inserted their placards amongst the candidates’ signs. Hilarity.

@Steven L. Taylor:

You’re probably correct, but I’ll get back to you on Wednesday or Thursday after we see how good/bad the turnout is this year. The ballots were initiatives and referendums, with no state of federal offices.

@Michael Cain:

As a fellow Colorado resident, I felt the initiatives this year were particularly confusing, especially for the vast majority who won’t realize that one is already the subject of a lawsuit and another was preemptively de facto altered by the state legislature.

The school district candidates were particularly frustrating for me as about half the candidates were anti-CRT crazies and the other half were pro-DEI crazies. Fortunately, I think (hope) I found three to vote for who care more about fundamentals.

@Andy:

Yep, absolutely. There are probably less than a thousand people in the state with the knowledge and experience to understand what Amendment 78 is about and the actual impacts. Not the kind of initiative that drives turnout.

@Michael Cain: For things like that, and we get a number of them in Washington most years, I always vote to maintain the status quo. If no one can explain the problem, then we don’t need a solution.

It’s a mixture of my small-c conservative nature, and my cantankerous “why are you bothering me with this? Lemmelone.” nature.

(small-c conservative nature, but not politics — I am basically a socialist incrementalist, which is the worst kind of socialist. “What do we want? As much economic and political freedom and liberty for the working classes as possible without creating unintended negative consequences! When do we want it? Ok, hear me out, let’s keep moving in that direction, bit by bit, until we start seeing some significant unintended negative consequences, and then back off, and I think we will have found the pragmatic optimum within the next 30-50 years.”)

@Michael Reynolds:

100% of snowflakes are made up of individual water molecules. What’s your point?

“You can’t assume anything in politics. That’s why every Saturday I walk around my district. I talk to the longshoremen in Charlestown. I listen to the people in East Boston and their concern on the airport noise. I walk down to the Star Market in Porter Square, and people tell me about meat prices.”“How odd!” exclaimed Senator Sinema. “Every Saturday I call my corporate donors or meet with them. I listen to a billionaire say how angry she would be to have to pay more tax. I listen to a pharmceutical company tell me how wrong it would be to lower drug prices. You can’t assume anything in politics.”

@DrDaveT:

My point? That using snowflakes as an analogy is pretty lame? Maybe leave that to the professionals?

You’re trapped by your own assumption that humans should be defined as ‘part of’, not things unto themselves, discrete and unique. That’s why you go to water molecules in snowflakes. In that analogy the snowflake is the thing, the molecule is just an element of the thing. The individual in your formulation is just a cog not a machine (weak, cliché), just a letter not a word (hmmm, I like that one), just a note not a song (eh, I’ve only had two sips of coffee).

IOW, my position is humanistic – we are each particular, specific and un-reproducible. The human matters.

You take the more, well, fascistic or totalitarian position, in which the individual is nothing but a piece of something greater.

I reject the idea that I am a part. I’m actually the thing.

@DrDaveT:

To carry on a bit more. We group people for convenience. So that those groups of people can be moved around like pawns on the chessboard, or dropped into algebraic equations. But that’s for convenience, it’s not for accuracy. We choose to ignore the individual because they’re hard to count and hard to generalize about. But of course any time we create a set of humans we end up using a shoehorn and a mallet, because humans don’t actually fit very well into these made-up groups.

The set of all humans, the set of all male humans, the set of all female humans between ages X and Y, the set of humans with more or less melanin, the set of humans who attended Yale rather than Harvard. You can drop parentheses anywhere you like, they’re free, but in defining a set you lose data rather than gain it. You have to sand off the rough edges, water down the inconsistencies in order to then form a set. Because again, sets are easy, individuals are complicated.

But we have computers now and they count real good. I’m suggesting that rather than go on inventing bullshit sets of humans, we start looking into ways to analyze and approach voters as individuals. The Netflix algorithm sees me as an individual – it’s never right, but at least it’s trying to appeal to me as an individual decision maker. Amazon doesn’t think I’m a water molecule in a snowflake, Amazon caters to me, as me, not as part of the set of all sexagenarians living in LA.

I’m pointing out that in politics I am shoehorned into sets where I don’t actually fit. My decision making approach may not fit the set. My attitudes may be wildly at variance from the set, but I’ll still be trapped in the set. I’ll still be targeted for political messaging based on my presumed membership in sets A, B, M, R and W. The messaging will actually have the effect of bullying me into compliance, into accepting the sets defined by my betters.

@Michael Reynolds:

No biologically.

No psychologically.

Just no.

Do people have unique experiences? Yes.

Can we identify people via stastical analysis of their DNA? Yes.

Does that mean that those unique individuals aren’t strongly influenced by other unique individuals? No.

—

I think you may have missed the point of the snowflake analogy, but I’m going to wait for the Doctor of Mathematics explain what he meant.