Political Vitriol and Political Violence

The relationships between inflammatory rhetoric and political violence is complicated.

In the wake of the weekend’s shooting spree by Jared Loughner, which killed six people and critically injured Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, there has naturally been a lot of discussion about the strident tone of our recent political debate. While rejecting this rhetoric has been a constant theme of OTB since quite literally its beginning (see “How Not to Argue” from Day 1) we’ve nonetheless rejected the notion that those who use heated rhetoric in otherwise peaceful speech are in any way responsible for Loughner’s actions.

The two beliefs are in no way contradictory.

Calling For Civility Yet Understanding Incivility

For civil society to flourish, people must be free to engage in a vigorous exchange of ideas. People are emotional creatures in addition to rational ones, and sometimes speech will be heated. And leaders will sometimes use colorful language to play to the crowd, especially when talking to their supporters.

At the same time, the purpose of free speech is, ultimately, persuasion. And beginning with the premise that those who disagree with you are evil, stupid, or treasonous makes persuasion impossible.

Recognizing the former, we must tolerate some degree of excess in rhetoric, so long as it stops short of the direct incitement of violence. Recognizing the latter, we should encourage more respectful dialog.

Rhetoric, Violence, and the Law

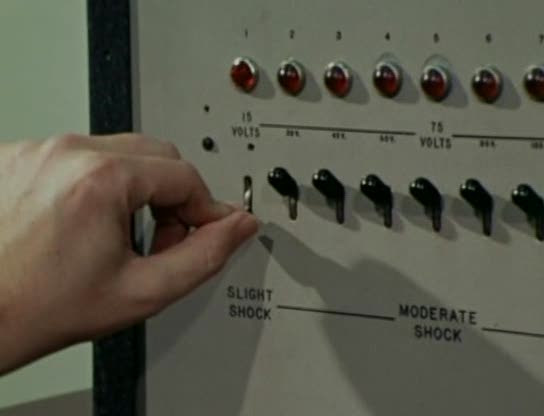

The Supreme Court has drawn the line as to the legal limits of free speech. While the First Amendment’s plain reading would seem to allow no government interference whatsoever, it has long been recognized that words that directly lead to injury are not protected. The famous case of falsely shouting Fire! in a crowded theater is the classic example.

Judge Learned Hand articulated the modern concept nearly a century ago, when he said that government may prosecute words that are “triggers to action” but not those that are mere “keys to persuasion.”

The Supreme Court formalized this in 1969 in what is known as the Direct Incitement test: “The constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

Under this doctrine, even the actual advocacy of violent crime can not be punished, so long as said advocacy remains theoretical. The case in question involved prosecution of the leader of a Ku Klux Klan group for “advocat[ing] . . . the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform” and for “voluntarily assembl[ing] with any society, group, or assemblage of persons formed to teach or advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism.”

Rhetoric, Violence, and Social Science

Just because it’s legal for people to use inflammatory rhetoric doesn’t mean it’s a good idea, of course. Indeed, as noted at the outset, I think it’s a bad idea if for no other reason than its corrosiveness of our national dialog.

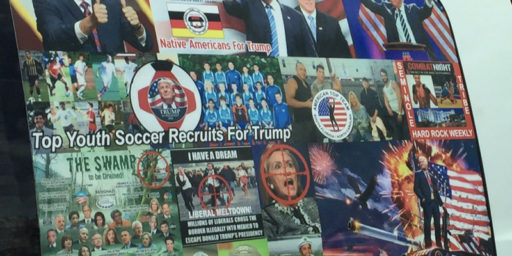

Does using quasi-violent words and imagery, including implicit suggestions that one’s political opponents are “the enemy” who must be “targeted” and that “2nd Amendment solutions” might be necessary actually lead to violence?

The social science literature on the subject, as John Sides notes, is rather mixed. The short answer seems to be that it doesn’t have that effect on normal people but might on people already predisposed to violence. He cites, in particular, a paper by Nathan Kalmoe which finds that “even mild violent language increases support for political violence among citizens with aggressive predispositions, especially among young adults.”

The specific language he tested were substitutions of the more peaceful “work” for the more aggressive “fight.”

Americans today are fighting/struggling to keep their jobs and their homes. All you ever asked of government is to stand on your side and fight/stand up for your future. That’s just what I intend to do. I will fight/work hard to get our economy back on track. I will fight/work for our children’s future. And I will fight/work for justice and opportunity for all. I will always fight/work for America’s future, no matter how tough it gets. Join me in this fight/effort.

I would note that all of the significant presidential candidates in 2008 used variations on the “I will fight” theme and that none of us considered this in the least bit provocative (except, perhaps ironically, for Sarah Palin, who’s convention speech accepting the vice presidential nomination mockingly noted “There is only one man in this election who has ever really fought for you”). The “dangerous rhetoric” we’re talking about in the wake of Loughner’s crime is far more vitriolic.

And yet, while “Seeing one or both of the ‘violent’ political ads had NO overall effect on support for political violence,” Kalmoe found “Seeing violence political ads DID have an effect among those with a predisposition to aggression, as measured with a standard psychological battery. Among those with the greatest predisposition to aggression, being exposed to a violent political ad increased their support for political violence by about 20 points on a 100-point scale. Among those with the least predisposition to aggression, being exposed to a a violent ad actually decreased their support for violence.”

From this, Sides concludes that,

For information — vitriolic political discourse in this case — to influence Loughner’s attitudes and behavior, he would have had (1) to be exposed to that discourse and (2) to accept or believe what he was hearing. Was he? We do not know.

To prove that vitriol causes any particular act of violence, we cannot speak about “atmosphere.” We need to be able to demonstrate that vitriolic messages were actually heard and believed by the perpetrators of violence. That is a far harder thing to do. But absent such evidence, we are merely waving our hands at causation and preferring instead to treat the mere existence of vitriol and the mere existence of violence as implying some relationship between the two.

Rhetoric, Violence, and the Duty to Worry About Nuts

While I concur in this insofar as it goes, I would add two caveats.

First, while I advocate keeping debate civil and eschewing violent rhetoric in addressing domestic politics for all manner of reasons, the potential impact of the words on the mentally unstable is least among them. As Doug and Steven have argued well in their posts on the matter, we are failing in our care for the mentally ill in this country, including those with violent tendencies. But I’d stop short of saying that we have some duty to censor our speech because some unstable person might react absurdly.

Second, there are different standards for the yahoos and those who would lead them.

While I’ve decried the poisonous atmosphere of some of the Tea Party rallies and the shoutfests at some town hall meetings, I’m not overly concerned about the yahoos who hold up “We came unarmed (this time)” signs at rallies. I honestly think that they’re mostly decent citizens, frustrated with their government, and emboldened in their speech by the safety of a likeminded mob. While not exactly helpful in persuading those who disagree with them as to the wisdom of their position, it’s just false bravado and cathartic venting.

Conversely, while I in no more blame Sarah Palin, Michelle Bachman, and Sharron Angle for Jared Loughner than I do Al Gore and Ralph Nader for Ted Kaczynski, I do think they have a duty to be more responsible in their choice of words. Not so much because ratcheting up the rhetoric might set off some nutcase but because it’s an unmitigated negative for our body politic.

If someone’s office is shot at, would it be reasonable to expect them to take down ads with gunsights on them? What should we think of those who do not?

Steve

Comment in violation of site policies deleted.

Those wishing to buy advertising should send inquiries to ot*@bl*****.com

Lord Almighty, you sure convinced me. What a brilliant conclusion. Why are you sorry?

OK, Ronin, now you’re just re-spamming the same lame liberal talking points on multiple posts with cut and paste. Time for you to get back on your meds.

Correction: They’re not even liberal talking points. the liberals are being more responsible than that, they’re just lame. Chalk it up to just shooting from the hip.