Raul Castro Says he is Willing to Talk

The US government has an odd and unproductive view on the concept of talks.

Via the AP: Raul Castro: Cuba willing to sit down with US

Via the AP: Raul Castro: Cuba willing to sit down with US

At the end of a Revolution Day ceremony marking the 59th anniversary of a failed uprising against a military barracks, Castro grabbed the microphone for apparently impromptu remarks. He echoed previous statements that no topic is off-limits, including U.S. concerns about democracy, freedom of the press and human rightson the island, as long as it is a conversation between equals.

“Any day they want, the table is set. This has already been said through diplomatic channels,” Castro said. “If they want to talk, we will talk.”

Now, do I think that it is likely that democracy and human rights would flower quickly and with ease if the US sat down with the Cuban government? No. However, do I think we all would be moving in a more positive direction if we did so? Yes.

The evidence is pretty clear: the lack of talking has hardly lead to liberalization on the island. Nor, I would note, has it really been of any use to the United States over the last two decades. The policy, quite frankly, makes no sense.

Further, as I have maintained for quite some time: liberalization becomes more likely via engagement, not by continued isolation.

Unfortunately, US terms for talking are illogical:

Later Thursday, Mike Hammer, assistant secretary for public affairs at the U.S. State Department, said that before there can be meaningful engagement, Cuba must institute democratic reforms, improve human rights and release Alan Gross, a Maryland native serving 15 years for bringing satellite and other communications equipment into Cuba illegally while on a USAID-funded democracy-building program.

“Our message is very clear to the Castro government: They need to begin to allow for the political freedom of expression that the Cuban people demand, and we are prepared to discuss with them how this can be furthered,” Hammer said. “They are the ones ultimately responsible for taking those actions, and today we have not seen them.”

In other words, the US is willing to talk about democratization and liberalization only if Cuba would democratize and liberalize. This is just like the US insisting that the it will only speak to Iran about stopping its nuclear program if it first stops its nuclear program or the notion that Israel can only negotiate with the Palestinians about recognizing Israel’s right to exists if the Palestinians will first recognize Israel’s right to exist.

It is as if on the hard question the US government will only talk if the problems are pre-solved. Perhaps it is the thought that “talks” mean “celebration of the achievement of all goals and the resolution of all problems” instead of “a starting place for negotiation to figure out how to solve difficult and intractable problems that aren’t solving themselves.”

Without a doubt mutual signs of goodwill (such as the release of Gross) are reasonable expectations. However, the notion that the major issue that would require negotiations could be solved sans said negotiations.

By the way: I recognize that talks of the type described herein are hardly a guarantee to solve anything. However, these problems are hardly solving themselves and the unwillingness to increase communication and mutual understanding strikes me as counterproductive.

There is also the argument that talks will legitimize the adversary in question. However, if we think about Cuba, it is worth noting that the currently regime has been in place since 1959. I am pretty sure it acquired all the legitimacy it was going to need some time ago. And, ironically, the US has actually empowered that regime by treating it like a major adversary, even well after its strategic significance (which was linked directly to the Cold War and not to any inherent power) evaporated.

Send Mitt!

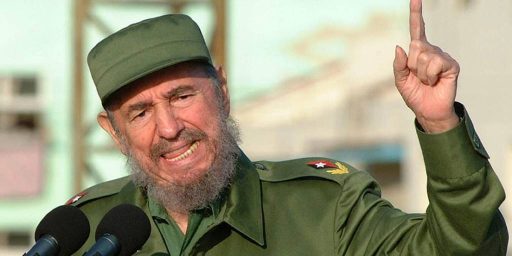

This reminds me of an old Johnny Carson skit. He was playing Reagan at a press conference and one of the “reporters” asked him if he would recognize Fidel Castro. Carson/Reagan said “Of course I’d recognize him, he’s got that scruffy beard and always wears that silly hat.”

More seriously, yea it’s time to change our policy toward Cuba but, to quote Tim Russert, there’s one obstacle in the way “Florida, Florida, Florida”

@Doug Mataconis:

Indeed. Along with corn subsidies for Iowa, a clear example of how our system for electing the president perverts public policy.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I don’t think you can ascribe this all to the way we elect Presidents, thought that likely plays a part. The Florida Congressional delegation is large enough to have quite an influence on policy in Congress, and many of the barriers restricting US relations with Cuba are rooted in laws passed by Congress

@Doug Mataconis: When it comes to foreign policy decisions, every president (and candidate) knows that their election/re-election can come down to a few percentage points in Florida. Given that, there is no reason to risk offending Cuban-Americans. I think it is a central reason for the general policy path, especially in the post Cold War era.

What candidate would risk insulting those voters after 2000 in particular?

“More seriously, yea it’s time to change our policy toward Cuba but, to quote Tim Russert, there’s one obstacle in the way “Florida, Florida, Florida””

True enough, especially in an election year where no one wants to look soft on an old adversary. I suspect that more progress may be made in 2013, regardless of the winner of the election.

@Steven L. Taylor:

You have a point, but it’s also true that any President who wants to open relations with Cuba will have to deal with a few laws that Congress has passed over the years.

@Doug Mataconis: This is quite true. It is also true, however, that there is leeway for the executive in a number of those laws. Including issues like travel, communication, financial transfers, and even trade.

I would further note that there are large constituencies in some pretty conservative states (including the poultry industry in Alabama) quite interested in trade with Cuba (the port of Mobile is ideal for such trade as well). There is room to move on this topic and there is little doubt that a major obstacle is the Cuba-American vote in Florida (which you yourself noted).

At a minimum: it is quite clear that that bloc of voters has a radically disproportionate amount of influence on this policy area.

Yes – have a talk with brother Raul. Get trade reopened, get developers (Trump) down there, and get the internet to everyone. Cuba will once again be on the list with Bahamas, Puerto Rico, etc.

Can’t wait on some cigars – just to show people!

The cigars are obviously a priority. Also, baseball

As long as we care about Florida’s Cuban Republicans, it’s not going to happen while Fidel is alive. And for all we know, as long as Raul is alive too.

It ridiculous that we’ve been locked into the current policy for over 50 years.

About the only hope for sensible US policy on Cuba is for the older right wing Cuban Americans to die off faster. Sad but true.

Excellent post, Mr. Taylor.

Please clarify for me, if you will, what you mean by “talks.”

The U.S. wants: Cuba to democratize and liberalize; Iran to end its nuclear program; Palestinians to recognize Israel’s right to exist. In pursuance of these goals, the U.S. government is already engaged in back channel “talks” with these countries. Plus, the U.S. is expressly talking about these goals right now in the sense of trying to persuade the leaders and peoples via intellectual sources and mass media, etc.

What the U.S is apparently unwilling to do – I gather – is engage in high-level talks (read as “summit”?) and/or negotiations. You suggest the U.S. is only willing to engage in high-level talks with these countries on the condition that their primary goals are first met; but, if that were to happen, there’d be no need to negotiate over goals that are already achieved. Thus, you wonder if the U.S. is only interested in talking as “celebration of achievement of all [primary] goals.” But, in that context, talking would not mean negotiation, unless maybe the U.S. then moved on to negotiate other, newer items made possible as a result of achieving pre-conditions (e.g., financial aid, trade, etc.).

You recommend, instead, that the U.S. engage in high-level talks with these countries, in which “talks” might be seen as vehicles for persuasion, problem solving workshop of sorts, and forums for negotiations. However, you also stated that the U.S. key goals can be achieved only through negotiation, implying that persuasion and/or problem-solving are insufficient alone. In that context, then, “talking” really means high-level negotiations.

Yet we might assume that such high-level negotiations are ultimately of value only if both sides are willing to negotiate on democratization/liberalization (Cuba), the bomb (Iran), recognition of Israel (Palestinians). Do we know that to be the case? And, if not, are you suggesting that high-level talks really can be vehicles for persuasion, even though the main issues described in your post “require” negotiation to make progress?

Maybe you would please clarify some of these tensions.

I think just about anyone without an axe to grind who sits down and looks at the situation would conclude that our policy is counterproductive.

But, yeah, “Florida” (also, too: election year).

@Steven L. Taylor:

Granted this is about ethanol, not corn subsidies per se, but the ethanol subsidies expired on Dec. 31, 2011 (a few days before the Iowa caucuses) and it was a big, fat nothingburger.

Changes to the Cuba policy will most likely go like ethanol subsidies, or SSM. When the change actually comes, people will mostly go, “What was the big deal?”

It’s getting to the point of change that will be the hard part.

As we know, with Mr. Obama policy change tends to arrive at exactly one minute past “no one cares anymore.”

@al-Ameda: @stonetools: I think you’re both correct in this case. No administration wants to be seen negotiating with la familia Castro because of the complete reversal of long-standing but stupid policies and as long as the older ex-pats are alive in Florida.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Luckily climate change will solve these issues for us. Once Iowa is a sun-seared wasteland and Florida sinks beneath the ocean waves thanks to Hurricane Gargantua in 2034, we will finally be able to enter negotiations with the Communist mer-people that live beneath the waves of what was once the island of Cuba.

Of course, our future Presidents will probably be giving billions in sand subsidies to Iowa and courting the mer-people ex-pat vote in Florida by then. So it goes.

@stonetools: This is true. The original Cuban refugees were the oligarchs that were responsible for the conditions that led to the revolution in the first place. Most of them are already dead. The second generation continued their anger and bitterness. The third generation less so and the fourth generation wants normalization. It won’t be long.