SCOTUS Weakens Pre-Election Ad Ban

The Supreme Court today severely weakened a key provision of the McCain-Feingold law.

The Supreme Court loosened restrictions Monday on corporate- and union-funded television ads that air close to elections, weakening a key provision of a landmark campaign finance law. The court, split 5-4, upheld an appeals court ruling that an anti-abortion group should have been allowed to air ads during the final two months before the 2004 elections.

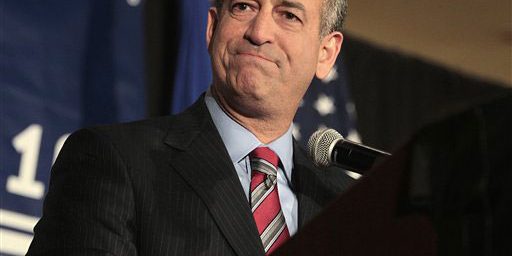

The case involved advertisements that Wisconsin Right to Life was prevented from broadcasting. The ads asked voters to contact the state’s two senators, Democrats Russ Feingold and Herb Kohl, and urge them not to filibuster President Bush’s judicial nominees. Feingold, a co-author of the campaign finance law, was up for re-election in 2004.

The provision in question was aimed at preventing the airing of issue ads that cast candidates in positive or negative lights while stopping short of explicitly calling for their election or defeat. Sponsors of such ads have contended they are exempt from certain limits on contributions in federal elections.

Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by his conservative allies, wrote a majority opinion upholding the appeals court ruling. The majority itself was divided in how far justices were willing to go in allowing issue ads. Three justices, Anthony Kennedy, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, would have overruled the court’s 2003 decision upholding the constitutionality of the provision. Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito said only that the Wisconsin group’s ads are not the equivalent of explicit campaign ads and are not covered by the court’s 2003 decision.

Roberts has signaled early in his tenure as Chief that he is more interested in crafting the widest possible consensus on the Court than in issuing sweeping decisions. That he was only able to get a bare majority for such a tepid ruling, therefore, would seem to indicate that this was as far-reaching as the Justices were willing to go.

While I’m disappointed, it’s not surprising that the Court didn’t overrule its recent decision upholding the constitutionality of BCRA. Doing so would have undermined the public’s faith, such as it is, that the Court is a group of oracles telling us what the Constitution says rather than a caucus of politicos making public policy based on how many votes they can cobble together.

The Opinion is here in PDF format; no, I haven’t read it yet.

UPDATE: I see Dodd was posting on this decision, along with the “Bong Hits for Jesus” case, as I was writing this post. I’ll leave both up, since they’re complementary rather than redundant.

Roberts is amazing. In back-to-back opinions he takes completely opposite stances. On the subject of campaign advertising, he believes that an “intent-based test” is unreasonable:

But, in the case of bongs, the intent of the speaker is just the thing:

So, according to Roberts, you cannot have an intent-based restriction on free speech in the case of a political campaign, but you can have an intent-based restriction in the case of speaking about drugs.

Brilliant.

Actually, on that score the two opinions are consistent. As I pointed out in my post, the dissent focused on the intent of the speaker as part of its reason for finding a First Amendment violation here. Roberts declined to do so, looking instead at what message a third party might reasonably find in the speech in question.

The dissent argues that the supposed pro-drug message isn’t a terribly reasonable interpretation – a matter of opinion I am not personally inclined to disagree with. Nevertheless, the focus here is on the receiver, not the sender, in this test, so it’s not a fair description of Roberts’ opinions to say that they contradict one another.

Are you taking bong hits again, James? I can’t understand a thing you just wrote. Put your aspiring writer hat away and just tell us what you think.