Syria: What Now?

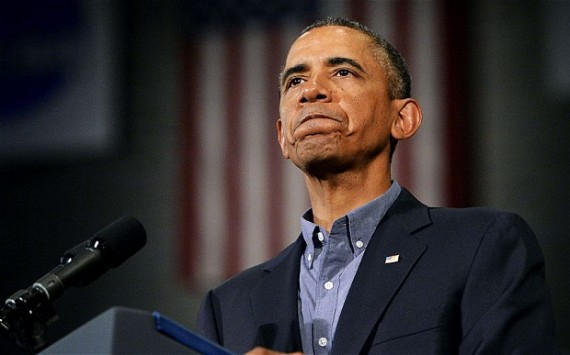

As President Obama's red line has been crossed more brazenly, he continues to sound reluctant to intervene in Syria while positioning forces to do just that.

As President Obama’s red line has been crossed more brazenly, he continues to sound reluctant to intervene in Syria while positioning forces to do just that.

Defense News‘ John T. Bennett summarizes (“Obama’s Iraq Concerns Central To Syria Policy“) the president’s thinking out loud on this issue:

President Barack Obama made clear on Friday he is unlikely to plunge US military forces into Syria’s civil war, citing the likely costs and potential for American casualties.

Obama swept into office in 2008 warning about the George W. Bush administration’s ill-fated war in Iraq. During a television interview, Obama rekindled his concerns in explaining why he has so far opted against a Syria intervention mission.

Obama said he is “sympathetic” to interventionist lawmakers like Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., who favor getting involved to help end a civil conflict that has claimed more than 100,000 lives. ”I am sympathetic to Sen. McCain’s passion for helping people work through what is an extraordinarily difficult and heartbreaking situation, both in Syria and in Egypt, and these two countries are in different situations,” Obama said on CNN’s “New Day” program.

Obama, however, then pivoted to rhetoric that sounded a lot like that of 2008 candidate Obama. ”But what I think the American people also expect me to do as president is to think through what we do from the perspective of, what is in our long-term national interests?” Obama said. ”And, you know … sometimes what we’ve seen is that folks will call for immediate action, jumping into stuff, that does not turn out well, gets us mired in very difficult situations, can result in us being drawn into very expensive, difficult, costly interventions that actually breed more resentment in the region,” Obama said, clearly alluding to the Iraq war.

Obama acknowledged that “the United States continues to be the one country that people expect can do more than just simply protect their borders.” But does that mean America should be the world’s policeman or firefighter? ”That does not mean that we have to get involved with everything immediately,” Obama said. “We have to think through strategically what’s going to be in our long-term national interests, even as we work cooperatively internationally to do everything we can to put pressure on those who would kill innocent civilians.”

Last August, Obama declared that should Assad use chemical weapons against Syrian citizens or opposition forces, it would constitute a “red line” for the American commander in chief. ”We have been very clear to the Assad regime, but also to other players on the ground, that a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized,” Obama said then. “That would change my calculus. That would change my equation.”

Since then, Obama and other Western and regional officials believe Assad’s forces have done just that several times. Yet Obama has done little to get directly involved, taking only small steps to aid opposition forces. A year later, it remains unclear just what “change my equation” means. It’s also unclear if Obama will ever come to side with McCain and other GOP interventionists, who feel Syria’s instability is a US national security issue that warrants direct military action. Many of Obama’s Democratic allies in the Senate, in conversations with Defense News, for months have criticized the president for making the red-line declaration then failing to enforce it.

Asked about his red-line remark, Obama seemed to revert to the constitutional-lawyer-in-chief persona for which many Republican and Democratic pundits have panned him. ”You know, if the US goes in and attacks another country without a U.N. mandate and without clear evidence that can be presented, then there are questions in terms of whether international law supports it, do we have the coalition to make it work,” Obama said. “And, you know, those are considerations that we have to take into account.”

Obama also appeared to pour cold water on any chances for a US mission in Syria by talking about the price military members have paid in America’s two major wars since the 9/11 terrorist attacks. ”But keep in mind, also, Chris — because I know the American people keep this in mind — we’ve still got a war going on in Afghanistan,” Obama said to CNN anchor Chris Cuomo. ”You know, we’re still spending tens of billions of dollars in Afghanistan. I will be ending that war by the end of 2014, but every time I go to Walter Reed [National Military Medical Center] and visit wounded troops, and every time I sign a letter for a casualty of that war,” Obama said, “I’m reminded that there are costs and we have to take those into account as we try to work within an international framework to do everything we can to see Assad ousted.”

This is a prudent assessment. It’s essential that the commander-in-chief weigh the costs of intervention into conflict and think through the consequences. Issuing the red line policy was an unforced error. Not following through makes him look foolish and makes the United States look weak to friend and foe alike. But doubling down and getting America into yet another war in the region would be a grave mistake, especially given the long odds against success at a price we’re willing to pay.

But, of course, just because there are no good options doesn’t mean that doing nothing is without cost. As Walter Russell Mead points out, the costs of non-intervention have been steep:

As the war has dragged on, the humanitarian toll has grown to obscene proportions (far worse than anything that would have happened in Libya without intervention), communal and sectarian hatreds have become poisonous almost ensuring more bloodletting and ethnic and religious cleansing, and instability has spread from Syria into Iraq, Lebanon and even Turkey. All of these problems grow worse the longer the war goes on—but it is becoming harder and costlier almost day by day to intervene.

But beyond these problems, the failure to intervene early in Syria (when “leading from behind” might well have worked) has handed important victories to both the terrorists and the Russia-Iran axis, and has seriously eroded the Obama administration’s standing with important allies. Russia and Iran backed Bashar al-Assad; the president called for his overthrow—and failed to achieve it. To hardened realists in Middle Eastern capitals, this is conclusive proof that the American president is irredeemably weak. His failure to seize the opportunity for what the Russians and Iranians fear would have been an easy win in Syria cannot be explained by them in any other way.

While the administration seems not to have forecast any of this (and, in fairness, neither did I) they’re certainly well aware of it. They’ve wrestled with the options for two years now and keep coming down in the same place: not now. And the escalation of violence that makes the need to “do something” appear more urgent makes decreases our ability to solve the problem that much harder.

Obama has steadfastly insisted that any humanitarian intervention requires UN Security Council approval. We got it in Libya but, paradoxically, that campaign has strengthened Russian and Chinese resolve against authorizing force again. Now, it appears, the administration is at least thinking hard about ways to legitimize intervention while sidestepping the veto issue. As Mark Landler and Michael Gordon explain for the NYT (“Air War In Kosovo Seen As Precedent In Possible Response To Syria Chemical Attack“) the 1990s are one such model.

Kosovo is an obvious precedent for Mr. Obama because, as in Syria, civilians were killed and Russia had longstanding ties to the government authorities accused of the abuses. In 1999, President Bill Clinton used the endorsement of NATO and the rationale of protecting a vulnerable population to justify 78 days of airstrikes.

A senior administration official said the Kosovo precedent was one of many subjects discussed in continuing White House meetings on the crisis in Syria. Officials are also debating whether a military strike would have unintended consequences, destabilize neighbors like Lebanon, or lead to even greater flows of refugees into Jordan, Turkey and Egypt.

“It’s a step too far to say we’re drawing up legal justifications for an action, given that the president hasn’t made a decision,” said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the deliberations. “But Kosovo, of course, is a precedent of something that is perhaps similar.”

[…]

Other Western officials have been less cautious than Mr. Obama. “I know that some people in the world would like to say that this is some kind of conspiracy brought about by the opposition in Syria,” said William Hague, Britain’s foreign secretary, in an interview with Sky News. “I think the chances of that are vanishingly small, and so we do believe that this is a chemical attack by the Assad regime.”

Mr. Hague did not speak of using force, as France has, if the government was found to have been behind the attack. But he said it was “not something that a humane or civilized world can ignore.”

Such statements carry echoes of Kosovo, where the Yugoslav government of Slobodan Milosevic brutally cracked down on ethnic Albanians in 1998 and 1999, prompting the Clinton administration to decide to act militarily in concert with NATO allies.

Mr. Clinton knew there was no prospect of securing a resolution from the Security Council authorizing the use of force. Russia was a longtime supporter of the Milosevic government and was certain to wield its vote in the Security Council to block action.

So the Clinton administration justified its actions, in part, as an intervention to protect a vulnerable and embattled population. NATO carried out airstrikes before Mr. Milosevic agreed to NATO demands, which required the withdrawal of Yugoslav forces.

“The argument in 1999 in the case of Kosovo was that there was a grave humanitarian emergency and the international community had the responsibility to act and, if necessary, to do so with force,” said Ivo H. Daalder, a former United States ambassador to NATO who is now the president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

In the case of Syria, Mr. Daalder said, the administration could argue that the use of chemical weapons had created a grave humanitarian emergency and that without a forceful response there would be a danger that the Assad government might use it on a large scale once again. Dennis B. Ross, a former adviser to Mr. Obama on the Middle East, said that if the president wanted to develop a legal justification for acting, “there are lots of ways to do it outside the U.N. context.”

US presidents have never let the legalities of the UN Charter get in their way when they wanted to go to war. This president will be no different. Indeed, I’ve argued from the beginning that the Russian and Chinese vetoes served as an excuse for the administration’s preferred policy of non-intervention rather than actually preventing a desired intervention.

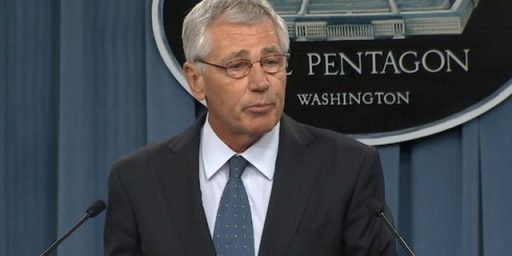

Nonetheless, the Secretary of Defense has ordered the movement of naval forces in the event action is desired, seemingly at the direction of his boss. Robert Burns for AP (“Hagel: Obama Asks For Syria Military Options“):

The Pentagon is moving naval forces closer to Syria in preparation for a possible decision by President Barack Obama to order military strikes, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel suggested on Friday. Hagel declined to describe any specific movements of U.S. forces. He said Obama asked that the Pentagon to prepare military options for Syria and that some of those options “requires positioning our forces.”

U.S. Navy ships are capable of a variety of military action, including launching Tomahawk cruise missiles, as they did against Libya in 2011 as part of an international action that led to the overthrow of the Libyan government.

“The Defense Department has a responsibility to provide the president with options for contingencies, and that requires positioning our forces, positioning our assets, to be able to carry out different options — whatever options the president might choose,” Hagel said.

Dan De Luce of AFP reports (“Hagel Suggests US Moving Forces Closer To Syria, Obama Cautious“) that the Sixth Fleet is staying put, too, although I seriously doubt it made that determination on its own.

Hagel’s comments came as a defense official said the US Navy would expand its presence in the Mediterranean with a fourth warship armed with cruise missiles. The US Sixth Fleet, with responsibility in the Mediterranean, has decided to keep the USS Mahan in the region instead of letting it return to its home port in Norfolk, Virginia. Three other destroyers are currently deployed in the area — the USS Gravely, the USS Barry and the USS Ramage. All four warships are equipped with several dozen Tomahawk cruise missiles.

At this point, it’s hard to believe that Assad is going to be bluffed into surrender or even serious behavior modification by signals that the United States is prepared to act. Not only is credibility going to be difficult to establish at this stage, the options for him and his Alawite faction are victory or utter defeat. And the former is looking like a pretty good bet at this point.

Reuters reports (“Obama’s National Security Team To Meet On Syria This Weekend“) that the gang will get together and talk about it.

President Barack Obama’s security advisers will convene at the White House this weekend to discuss U.S. options, including possible military action, against the Syrian government over an apparent chemical weapons attack earlier this week, a U.S. official said on Friday.

If Obama takes part in the high-level meeting as appears likely, it would be his first full-scale session with top foreign policy aides since Wednesday’s mass poisoning in a Damascus suburb.

But the official, speaking on condition of anonymity, cautioned against expecting that any final decision might come out of this next round of discussions.

My guess, and it’s nothing more than that, is that we’ll see more of the same. We could launch punitive strikes against Assad forces or headquarters without much risk to US forces. But to what end? Once military action is taken, it’s hard to make a case for stopping short of regime change. I’m confident that we could achieve that goal in relatively short order and at relatively little cost in US blood and treasure. But, as we’ve seen in Iraq and Afghanistan, that’s the easy part.

Knowing how nation states operate in geo politics, it’s pretty much a given that those with an interest in seeing U.S. military industrial complex money orchestrated this for the sole purpose of goading U.S. involvement into this. In the words of General Akbar of Star Wars, “It’s a trap!’

Perhaps the Syrian strongmen are jealous of all the villas the Afghan warlords got to build in France, etc and now want their turn to suckle on the Taxpayer teet. The President should order an airdrop of masks and chem bio suits as a humanitarian response. Chemical weapons lost their tactical advantage in warfare 60 years ago. The only value for the past 20 years has been their ability to draw the US into conflict.

In regards to appearing weak by issuing a red-line declaration and then doing nothing: better weak than foolish.

I’m sorry, James, but this is a slippery slope argument, and my rule is that slippery slope arguments are ALWAYS wrong.

We also have empirical evidence here. Israel has on a few occasions attacked targets in Syria, and have avoided doing any more than that. That shows its possible to do targeted strikes in Syria, without having to go whole hog and occupy thee country.

This is a case where we should “lead from behind.” There are no good options for us in Syria, so the best alternative is to get someone else to eat most of the shit sandwich, with us in support.

@stonetools:

Israeli strikes had a coherent strategic purpose. What coherent strategic purpose would justify US strikes? In other words, what is the political goal?

@stonetools:The USA is not Israel. We’re a superpower and the domestic politics of intervention in Syria are completely different. And, yes, as @Andy points out, Israel had very specific goals for targeted strikes. We, on the other hand, have never been attacked and will never be attacked by the Assad regime and have announced that “Assad must go.” So, having undertaken military intervention, why stop before Assad does that which he must do?

Thank god we have a President who’s willing to let us look “foolish and weak” in the short term, if it’s in our long-term best interest to not get militarily involved. Had either of the past two elections (especially ’08) gone differently, we’d probably already be fully embroiled in yet another middle eastern mess.

Btw, while we’re on the subject of making the United States look “foolish and weak” …

Didn’t the fact that President George Bush’s foreign policy was pretty much the antithesis of Teddy Roosevelt’s “speak softly and carry a big stick” advice, go a long towards furthering that image?

President Bush made many public pronouncements that could reasonably be viewed as bluster and bravado, then when we went into Iraq it turned out that our “big stick” wasn’t quite as effective as our enemies (and friends) had previously believed.

If the world views us as “weak” I think it probably has much more to do with the fact that nobody (other than maybe John McCain) actually believes that we could intervene in Syria, and change the dynamic “quickly and easily” .. or maybe even at all.

… but of course the current President can’t actually admit that.

@Andy: @James Joyner:

Actually, we don’t know for sure what Israel’s goals were. We just have rumor to go by.

As for the US goals in carrying out strikes, our stated goal can simply be enforcement of longstanding international law provisions prohibiting the large scale use of chemical weapons against civilians.

Now “realists” and “non-interventionists” may not like that reason, but it’s as good a reason as any for a limited series of airstrikes targeting Syria’s chemical weapons capability.

This is not an argument that we should carry out such strikes: Its an argument saying that there is a plausible reason for carrying out a limited air campaign in Syria.

Doesn’t have to be regime change. They may be thinking of removing his chem stocks, or most of them, and then leaving. May be trying to talk him into giving them up on his own too. Assad might as well, because they are much more likely to do him harm than be of use.

We would have had to endure the “weak” charge from some folks in any course of action other than full-blown regime change and nation building, including saying and doing nothing.

Has the president talked directly to this Assad guy? Sometime personal diplomacy can be effective. He does not have to go there in person. He has the phone or he could text him. Feel him out and see what he is thinking. Maybe he wants something and they could work out some kind of deal. Nixon talked to Brezhnev,and Reagan talked to Gorbachev. There is nothing wrong with talking.

Colonel Lawrence: are you busy right now?

Russia and the US know who did this..maybe the lack of reaction is because it wasn’t Assad?

Given we have no conclusive evidence of chemical weapon use by the Syrian government (the claim Assad’s forces are using them has been made and debunked before) the correct action is restraint. It is less than believable the Syrians would invite U.N. weapons inspectors into the country, then launch a chemical attack on the day they arrive only a few miles away. What we can safely conclude is that there are interest that really, really want a U.S. attack on the Syrian government and military and will do anything to see that happens.