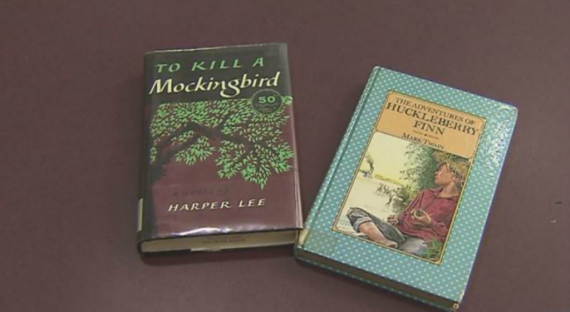

‘To Kill A Mockingbird’ And ‘Huckleberry Finn’ Banned By Minnesota School District

Two classic pieces of American Literature have been banned from the curriculum in Duluth, Minnesota. This is a mistake.

Two iconic pieces of American literature are being banned by school districts in Minnesota due to the fact that they contain a racial slur:

Novels by Harper Lee and Mark Twain have been pulled from school syllabuses in Minnesota over fears their use of racial slurs will upset students.

The Duluth school district said it was removing To Kill a Mockingbird and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from its curriculum because their content may make students feel “humiliated or marginalised”.

The school district, which includes more than 20 schools, said it will keep copies of the classic novels in its libraries but will be removing the texts on its curriculum for its ninth and 11th-grade English classes in the next academic year.

Michael Cary, the district’s curriculum director, said that its schools planned to replace the novels with texts that “teach the same lessons” without using racist language.

Both To Kill a Mockingbird, a Pulitzer-prize winning novel depicting racial injustice in Alabama, and Huckleberry Finn, which deals with slavery in pre-Civil War America, include racist characters who regularly use offensive language, including the N-word.

The two novels have been listed among the most banned or challenged books from 2001 to 2009 by the American Library Association, in large part because of their uncomfortable language.

According to the association, many of the complaints about Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird came from black parents concerned about a book containing a racial slur being taught in the classroom.

However, the texts are both widely considered to be anti-racist texts, using historically accurate language and characters to highlight and address the issue.

Mr Cary told local paper the Bemidji Pioneer: “We felt that we could still teach the same standards and expectations through other novels that didn’t require students to feel humiliated or marginalised by the use of racial slurs”.

The decision had come in response to complaints about the books’ offensive language over the years, rather than a specific complaint by a student, Mr Cary said.

The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People has supported the decision, saying it was long over due.

Stephan Witherspoon, the president of the local branch, said the books were “just hurtful”, adding that they use “hurtful language that has oppressed the people for over 200 years”.

However, free speech organisations have criticised the move, with the National Coalition Against Censorship, saying it was “deeply disturbed” by the decision.

“Rather than ignore difficult speech, educators should create spaces for open dialogue that teaches students to confront the vestiges of racism and the oppression of people of colour,” a spokesperson for the organisation said.

Bernie Burnham, president of the Duluth Federation of Teachers, said the district’s English teachers were concerned that they were not consulted before the decision was made.

“I don’t think anybody is averse to change – there’s obviously lots of great literature there that we can use with our students and are there reasons to walk away from that book? Probably – but we just want to be included in conversation about it,” she said.

This isn’t the first time that either book has raised ire among parents or school boards, of course. As noted above, a report from the American Library Association states that the two books were in the top 25 of the list of most banned or challenged books for the period from 2000 to 2009, and in the top 50 for the period from 1990 to 1999. They have also both made the list for years after 2009. More recently, a School District in Virginia pulled the book from its curriculum and school libraries in 2016 based on the complaint of a single parent but eventually reinstated them after an outcry from the community. Back in October, another district in Mississippi pulled the books after some parents complained that their language made them ‘uncomfortable.’ The book was later reinstated but the new policy stated that students could only read the book if their parents permitted it. Perhaps most famously, back in 1966 a school district in Hanover, Virginia banned Mockingbird after a school board member called the book ‘immoral literature,’ prompting Harper Lee to write a particularly biting letter chastising the decision that was published by the Richmond News-Leader:

Recently I have received echoes down this way of the Hanover County School Board’s activities, and what I’ve heard makes me wonder if any of its members can read.

Surely it is plain to the simplest intelligence that “To Kill a Mockingbird” spells out in words of seldom more than two syllables a code of honor and conduct, Christian in its ethic, that is the heritage of all Southerners. To hear that the novel is “immoral” has made me count the years between now and 1984, for I have yet to come across a better example of doublethink.

I feel, however, that the problem is one of illiteracy, not Marxism. Therefore I enclose a small contribution to the Beadle Bumble Fund that I hope will be used to enroll the Hanover County School Board in any first grade of its choice.

Harper Lee

It is true, of course, that both Mockingbird and Huckleberry Finn contain a word that most people today find to be deeply offensive and hurtful. At the same time, though, it’s also clear that both books are devoted to themes meant to combat and counteract that racism that this word, and other dialogue, in both books is there to lay bare the truth about the times that they depict. This, above all else, is what makes them among the most significant and important pieces of literature in American history. Rather than banning these books, school districts ought to be including them in the curriculum and encouraging teachers to use them as opportunities to engage students in discussions about the issues that they raise, including the power that a single word can have on the people who hear it. I wouldn’t recommend either book for young children, of course, but for students in the later years of High School, they both seem to me to be appropriate learning vehicles not only in English classes but also in American History classes when the focus is on the times with which both books take place. This strikes me as being especially important at a time like now when the ideas that these books are combatting seem to be on the rise again thanks in no small part to a President who has raised xenophobia to an art form and referred to white supremacists who marched through the streets of Charlottesville, Virginia as “very fine people.” Indeed, it’s unfortunate that an organization such as the NAACP would support a decision like this given the fact that banning the books seems to run counter to their own messages about teaching racial inclusiveness.

Outside of the particular issue of these books and the lessons they teach, it’s also disturbing to see something like book banning coming back into vogue in education. While it’s true that there are some fine works of literature that arguably are not age appropriate even for High School students, this most certainly isn’t true of either of these books nor is it true for the majority of the books on the ALA’s list of banned and challenged books. Book banning is a practice that brings echoes of authoritarian regimes and the idea that there are ideas that students should be shielded from, two principles that run counter to the notion of what education ought to be. Instead of banning books, schools ought to be encouraging students to read more, even if that includes books that challenge their notions about the world and even make them feel uncomfortable. Shielding students from the reality of the worlds that Mockingbird and Huckleberry Finn depict doesn’t make those eras of American history disappear, and it’s better that we talk about and learn from them then that we shield student from them because they might be momentariy ‘uncomfortable.’ Hopefully, the Duluth school district will see the error of its ways and reconsider its decision, but if the past is any indication that’s probably not going to happen.

![[Updated 1/31] Both Sides Are NOT the Same: "Banned" Book Edition](https://otb.cachefly.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/MausMockingbird-512x256.png)

The business of banning books has been taken over by the Left in this country. It has hit kidlit especially hard and a lot of writers (me included) are getting the hell out of Dodge because we’re turned off by the McCarthyite atmosphere. It’s sad, it’s weak and stupid and morally contemptible.

The blue-noses have taken charge. With sticks firmly inserted in their asses they are on a mission to cleanse the world of heresy, past, present or future. In this case the derisive term ‘snowflake’ very definitely applies. And all of the people responsible have read 1984, and Fahrenheit 451, and managed to come to the exactly wrong conclusions. Kind of makes you wonder why we bother to write books when even librarians are this clueless.

On the other hand, what a lovely sense of relief when I finally decided ‘screw it.’ It reminds me of walking out of High School or the time I left a waiting gig in mid-rush: here’s my tickets, have fun, and I am outta here. A manager actually told me I couldn’t leave mid-shift. Which of course made it all the sweeter.

Also, Doug, minor typo: It’s the Richmond News-Leader, not Reader. I used to be their restaurant reviewer.

I’m opposed on principal to banning books and I’m not a Southerner – which will be relevant in a moment.

But I’m gonna toss out an alternative idea: maybe, just maybe, it’s time to introduce some more up-to-date literature that addresses racism from a modern perspective? Books written by black people, for instance, with black characters? Like Coe Booth or Tanita Davis? Maybe kids might feed these more relevant than books over half a century old where the situations don’t reflect their lives? How many kids identify with Jim?

I think both books are good – although HF is a genuine classic; I’m not sure TKAMB is in the same category. But maybe the protesters might have a point?

@Not the IT Dept.:

And once we’ve removed library books for offending Group 1, we have to do the same for Groups 2, 3, 4. . . Anyone with a beef, anyone who wants to play victim. Let’s start by yanking Shakespeare, that old anti-semite. Or Dr. Seuss because Geisel used to work for the government in WW2 and produced racist stuff about the Japanese.

It’s not an either/or, we don’t have to pull Twain to make room for Jason Reynolds, we can have both. Should have both. And FYI, all of the top spots in the just-announced Newbery award went to POC, and all those books will be in libraries as a matter of course.

@michael reynolds:

Thanks fixed.

@Not the IT Dept.:

I think there is room for both books like Mockingbird and Huck Finn and more modern takes on these issues in the curriculum. Perhaps ass a ‘compare and contrast’ exercise that shows the differences and similarities between the ways that contemporary and classic literature and how they approach issues like race. After all, the importance of the two books in question is that they were written relatively contemporaneously with the times they are meant to depict, something that makes both of them important in discussions about racism in those particular periods.

This seems about as sensible as banning all movies in which a person is seen smoking.

Y’know, if you were to ask all these people if they believed in magic they’d say no, but they’re acting as if the mere statement of a certain epithet will call up horrible demons from the depth and tear them to pieces.. Totally ignoring that That. Was. How. People. Spoke. Back. Then. And the more one makes a fuss about “the N-word” the more importance and transgressive using it becomes….a vicious circle, no?

(I suspect that the use of “the N-word” is now so loaded with animus that it’s impossible to reclaim it as it probably entered a lot of literature of the period: the word “Negro”, but said with “a Southern or lower class accent.” Yes, I think disdain was attached, but didn’t it only really get started to be considered equivalent in evil to a swastika relatively recently?)

I speak, of course, as someone who knows very little about the history of the word’s usage.

@Doug Mataconis:

To be fair, that’s still not going to address @Not the IT Dept.Not the IT Dept’s point. For instance, as a woman, I can read classic literature for how women were treated and compare it to modern lit and get almost nothing out of it other then a vague sense of”wow, I’m really glad I wasn’t born then”. The situations are so far removed from a modern perspective they might as well be fantasy and we’re talking about Narnia instead of Victorian England. There’s a reason why women have latched onto A Handmaiden’s Tale instead of anything by the Brontës – as far-fetched as Gilead sounds, it’s far more likely to happen to a modern women then reliving the trials of being an old maid governess. Historical context is great but pointless out of scope; the older these stories get, the more they become just stories of the past instead of important lessons. The present should always be the focus since you can’t do anything about yesterday.

Don’t get me wrong – I still see value in classics like TKAMB and they should definitely never been banned. But we can’t keep using the same books over and over again like nothing of value has been produced since that’s worth using as a education guide to sensitive subjects. The scripts can change so long as the message remains consistent: these are some of the problems in the world and here’s why they are terrible things that must be addressed. For that, we need fresh blood so to speak to take precedence.

In my old neighborhood, there are covenants from 1928 that preclude “persons other than of the Caucasian race” from buying or renting property. In fact, they were not allowed on the streets in that neighborhood unless they were servants traveling to and from work.

You also couldn’t build a house there that was valued at under $5,000, and the garage had to be set back from the front of the house. Of course, those provisions expired January 1, 1950 – but not the racial one.

My point: The city could have cleaned up this old stuff after the Civil Rights Act outlawed such covenants, but it’s all still there. Anybody buying in that neighborhood today has to sign a document with this foul stuff on it.

I have come to the conclusion that, triggers aside, this is a positive thing. Let us not whitewash history, but rather see it for what it was, lest we repeat it in our lifetimes.

Thanks to KM for getting my point. HF is a classic and to me the Greatest American Novel Ever Written. (TKAMB is good, but not in HF’s league. Sorry, I’m rigid on this point.) I think people should read HF over and over again throughout life, like I do. But I also remember how great literature is taught in most schools and I remember how it resulted in me hating Charles Dickens, Dylan Thomas, Wordsworth, T.S. Eliot and Hemingway.

We learned Shakespeare the right way. The school invited a visiting British actor who was performing Macbeth (I think) in the nearest town and he showed up with his manuscript of Twelfth Night. He introduced himself to us as a “nancy” and a “flaming queer”, called us “cherubs” and cracked open the play to read every dirty joke from cover to cover – with hand gestures and body positions. The vice principal stood at the front of the class with sweat on his face, no doubt seeing his pension go up in smoke.

I don’t want kids to feel like I did when I was being bored out of my mind reading Tinturn Abbey.

The single best unit of English Lit that I had in high school was in 9th grade. Over the course of a quarter, we read To Kill A Mockingbird, then Freidrich, then Farewell to Manzanar.

Our teacher was quite canny (in a good way). She presented both To Kill a Mockingbird and Freidrich in the context of the history lessons we had already been exposed to by that point on the history of slavery and Jim Crow, and the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany.

And then, on a Friday, she handed out Farewell to Manzanar without any context whatsoever. She just told us that we had to read the first 50sih pages by Monday. She had to have known that none of us in the Boston suburbs in the early 80s had ever even heard of the Japanese American internment camps.

I engulfed that book in an afternoon. It haunts me to this day.

The article doesn’t say what the books are being replaced with, so this might not be as stupid as it sounds. I don’t know how you teach about offensive periods in American history without risking offending someone, though.

That said, there is the robotic edition of Huck Finn, which replaces every reference to darker skinned races with “robot” — making it perfectly fine in the classrooms of the easily offended. Or at least you won’t have a bunch of teenagers repeating the N word over and over in call, and can add a discussion of how to deal with the offensive parts of the past.

Sometimes stupid objections are best remedied in a stupid way.

Book banning is hardly a new thing. I have been reading about A Wrinkle in Time, my favorite childhood novel and soon to be released motion picture, and how it has been repeatedly banned by schools since its 1962 publishing. I also recall reading in high school The Day They Came to Arrest the Book, libertarian Nat Hentoff’s 1983 novelization about the repeated banning of Huckleberry Finn. The novel has various characters oppose the book for a range of reasons, including said offensive term, but also various other reasons for taking offense (“How dare they treat Southern whites as ignorant!” etc, etc.). He wisely chose an African-American high school student to make a passionate defense of Huck Finn, emphasizing the important messages that we all need to remember about this country’s history. For what it’s worth, as an African-American high school student reading Hentoff’s book, I agreed.

@grumpy realist:

Your description is actually quite accurate. The N-word began as a Southern pronunciation of “Negro.” It fit a pattern where they transposed the syllables in certain words: for instance, zebra was often pronounced “zebber.”

One thing I’ve noticed is that a lot of ethnic slurs are of unknown origin. That includes k!ke, sp!c, w*p, and more. They’re offensive for pretty much one reason: because everybody perceives them that way. You could probably have a computer spit out some random syllable, and if you convinced enough people it was a racial epithet, it would in effect become one.

In the case of the N-word, the crucial thing is that it arose in a society where white supremacy was taken absolutely for granted–where most blacks were little more than property. So whether a white person called a black person by the N-word or “Negro” or “colored,” they were pretty much expressing the same attitude.

Huck Finn is a pretty odd book–I’m going to guess that HS English has taught it poorly and without any of its caustic jokes for a hundred years. I mean, it’s hero basically decides he’s going to straight to hell rather than turn Jim in. I feel like there’s a million bad teachers saying this is an example of ‘irony’, rather than saying Twain thought America was sick and hysterically funny. Leftists are good at pointing out how sick America is, but they don’t get its f–ed up humor that well. And nobody else seems to get anything.

@michael reynolds:

I know people who are offended by the very idea of arithmetic, and would be completely on board with getting rid of that.

More seriously, is it possible to say anything at all about the world without offending someone? I kind of doubt it. You certainly can’t discuss any history, because every viewpoint will offend one person or another. I suspect the same is true for literature, and certainly for science, music, art, geography (where should border’s be etc).

It might be more useful to teach kids (and adults) how to deal with things they find offensive, since they’re going to run across things they disagree with every day of their lives.

@grumpy realist: The offensiveness of the use of the N-word goes back a lot further than “relatively recently.” Keep in mind that those on the receiving end of the word were aware of its offensiveness–reinforced with violence–long before it might have registered with most white people. It’s the reclaimed in-group use of the word that is more recent — the offensive use of the word goes way back. (Note that “in-group” is highlighted for a reason. The word is still offensive when used by people not within the group. And also note that “in-group” doesn’t mean that all African-Americans use it. In fact, I would wager that a majority do not).

The first time I read Huck Finn I was 11 years old and living about 100 miles from the Mississippi. I thought it was a great adventure story; what could be more fun than to float a big river getting away from grownups. I read it in college when I was 20 and full of the sarcasm that the young are prone to; I thought the book was a great example of mockery. I reread it when I was fifty and saw it as a great document of the true liberation of the human heart. Huck is an abused child running from a drunken child beater and prissy relatives who try to crush his soul. The only decent person who treats him with respect and love is Jim. Society calumnizes Jim with an ugly appellation, but Huck is able to see through this and to reject the evils that society forces upon us even if it means going to hell. Twain was a cynic and made us see the distortions that society imposes.

I love this book. Let me teach it. I might throw in some lyrics from the nearby town of Hibbin to illustrate the uses of irony.

@Kylopod: Well, that’s my question. When the Ni-CLANG! word was used in the South before, say the Civil War, was it considered a separate word from the word “Negro” or was it simply the spoken version of it? And did the use of the term “Negro” have the exact same (offensive) meaning attached to it?

I ask because it seems at least some point there seems to have developed a separate vocabulary to indicate “the good, God-fearing darkies” and “those lazy shiftless Ni-CLANG! types.” Sort of like the difference between “poor whites” and “white trash”. Did this distinction exist before the Civil War? Or when did the separation develop?

(Supposedly a similar epithet exists in French–the use of the term “Negre” but aside from Rimbaud using it in his poetry to shock everyone back at the turn of the century I haven’t run across other literary uses of it. And I have no idea how it’s considered in modern French culture. I do know that the French DID use to use the term “les noirs” which I guess was the polite version.)

@grumpy realist:

Well, here’s what the Online Etymology Dictionary reports:

According to Wikipedia:

American Jewish culture contributed the word “schvartze,” which is derived from the Yiddish word for a black person. (Technically, “schvartze” means a black female, and the word for a black male is “schvartzer,” but this distinction seems to have been lost in American speech, possibly due to the non-rhotic Jewish New York accent.) When I was growing up it was almost always a racist term (my parents hit the roof whenever they heard anyone use it), though not everyone who used it perceived it that way. The excuse was always “But it’s just the Yiddish word for ‘black’!” That was pretty much what Jackie Mason said after he was criticized for referring to David Dinkins as a “fancy schvartze with a mustache,” and later when he applied the term to Obama.

Around the time National Review fired John Derbyshire, they also canned another writer, a Jewish racist named Robert Weissberg who was found to have participated in the white nationalist American Renaissance conference. I saw a video in which Weissberg defended the use of the term “schvartze.” He insisted it was “not a derogatory term,” that it could even be “affectionate,” but that it “always, always implies cognitive inferiority.” Go figure.

In modern Israel, the equivalent of the N-word is kushi. It comes from a Biblical Hebrew word for an inhabitant of the ancient land of Kush, which is modern Ethiopia. In the Bible, Miriam criticizes Moses for the “kushi” woman he had married. God then punishes Miriam with leprosy, making her skin “white as snow.” When you look at these verses today, it’s hard not to escape the impression that Miriam was literally receiving divine punishment for making a racist remark about her brother’s wife. But this is probably imposing a modern outlook on the text; as far as I’m aware, there’s no record of this interpretation until the 20th century, and our modern concept of race simply didn’t exist in Biblical times.

While we’re on the subject of racial epithets in Jewish languages, the history of the word “Yid” is itself interesting. It’s nothing more, nothing less, than the Yiddish word for “Jew.” The name of the language itself literally means “Jewish.” Yeshiva Rabbis use the word all the time, with the plural being Yidden. But for some reason, the term became an anti-Semitic epithet among non-Jews. It’s different from the African American use of the N-word, where a previously deragotory term was being reclaimed; here, the process went in the opposite direction, but created the same outcome, where the term is regarded as acceptable in a Jewish mouth but racist in a Gentile one.

For that matter, the simple English word “Jew” has been loaded with controversy for centuries. There was a period of time in the late 19th to early 20th century when it was actually considered more proper to refer to Jews as “Hebrews,” which sounds totally quaint today. But “Jew” still remains a contentious term, and it’s often considered safer to replace it with the adjective “Jewish” when you can. A couple of months ago when Roy Moore’s wife tried to dispel charges of anti-Semitism by insisting “one of our attorneys…is a Jew!”, the statement was hilariously tone-deaf no matter how you cut it, but she certainly didn’t help matters by using that phrase “a Jew.”

Of course it would be an exaggeration to say you can never use the word “Jew,” but in many contexts it does have a rough edge. Anti-Semites often don’t even bother with the k-word or another outright slur; you frequently hear them talk about “the N***ers and the Jews,” as if the word “Jew” itself is parallel to the N-word. How it came to be this way, it’s hard to say. Of course the word sounds improper and racist when used as a verb (as in “to Jew down”) or an adjective (as in “Jew lawyer”), and it may be that these uses helped taint the noun form. But one way or another, it just goes to show that the perception of which words are derogatory is little more than a matter of common convention.

@michael reynolds: I see a parallel to what you’ve written about the #MeToo stuff, which was basically that someone being uncomfortable is too low of a bar. And I completely agree in both cases.

@michael reynolds: I wrote stories on the internet for over a decade before I began selling my work as ebooks. All but one of my major completed works is now available for sale at Amazon.

The one exception (Because it needs a good proofreading) features an important minor character who repeatedly uses the N word. Most of the time directed at the bi-racial girlfriend of his youngest son. The father’s views are the reverse of his closest family including his wife. The story was about redemption and forgiveness.

At one of the websites the story was published at, I rated it R with a note at the very beginning to warn my readers that was very offensive language used. The only reader who ‘complained’ was because the R rating was for language and not for sexual content. He was hoping for the latter.

This sort of thing is happening more and more. It will continue to happen until the people stand up.

Several years ago there was a similar outcry about “Huckleberry Finn”. This is more of the politically correct atmosphere, don’t offend anyone, avoid controversy, safe zones, no failure situations that is sweeping the country and the universities.

@Tyrell: I wonder if you realize that the biggest proponents of book banning have not been people on the politically correct left, but rather on the conservative and religious right.

@Tyrell: In fact, if you look at the list of the most commonly banned books in the U.S., the most commonly cited reasons are sexual content, profanity, and LGBT themes.

Not banned, simply “removed from the curriculum:”

“District officials in Duluth schools have removed the novels “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” from the required reading list so as to not subject high school students to the books’ use of a racial slur.

Michael Carry, the district’s director of curriculum and instruction, told The Duluth News Tribune that the books will still be optional reading and available in the school libraries, but they’ll be replaced next year by other books that touch the same topics without language that makes students uncomfortable.”

http://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2018/02/07/duluth-reading-list-racial-slur/

@Bill:

I’m starting to look seriously at self-publishing. The first time I heard 70% (the Amazon royalty) my little ears perked right up. I’m not great at math but I do know that 70% is bigger than 10% (typical royalty.) I haven’t done so yet because until recently I was on a sort of extended run of pre-sold deals and let’s face it, when someone offers you money it’s mighty hard to say no. Fortunately the wife is selling books like crazy (to younger age ranges) so for the first time ever I have the freedom to write without having to watch the bank account so closely.

But the atmosphere in kidlit is positively poisonous, and beyond the political sh!t there’s the ascendancy of library purchases relative to retail. Retail has fallen off a cliff because there’s no great engine driving it (Harry Potter, Hunger Games, Divergent) and the adults who were the bulk of readers for YA moved on to different fads. So the ‘schools and libraries’ wing, devastated by budget cuts, is nevertheless increasingly in the drivers seat. Which means teachers and librarians. We’re getting back to books-as-medicine, which will leave fewer and fewer kids actually reading.

The more prescriptive the approach, the duller the books, the less kids read, and down and down we go. Anyway, the fun times of the mid-2000’s, when Suzanne Collins and Veronica Roth and James Dashner and Andrew Smith and yours truly were having fun writing epics and experimenting and selling millions of books is over. Now it’s time for children to line up and take their ‘plight of victim XYZ’ medicine. On the plus side it will push male readers especially, but a surprising number of female as well, out of YA and around the corner into adult sci fi and fantasy. Which, by amazing coincidence, is where I’m going as well.

Whether by book banning, or by campaigns leading to book burning (mulching, actually), or simply by imposing their dour, humorless, eternally-offended mentality on kidlit, the Left has killed the thing they meant to support. Now we have to read things that are simultaneously ‘good for you’ and ‘absolutely inoffensive,’ which are two synonyms for boring. The 14 year-old who was still clinging to books has been abandoned to Netflix. Flash forward five years to the inevitable, “Why aren’t kids reading?” stories. I can give you the answer right now: because we forgot the kids and made it all about the adults.

TL;DR: I’m looking hard at that 70% plus maximum freedom offer, versus publishing’s 10% and very little freedom option.

As I have noted in several forums, including a post here earlier today, schools are reflections of the communities they serve. With that in mind, I see the future of book banning and suppression of disapproved ideas an emerging growth industry.

@Kylopod: Very interesting! Thank you very much!

I have noticed a tendency of 19th century and early 20th century writers to report black, Irish, and “ethnic” speech phonetically in fiction, while ignoring the accent of other individuals. Lower class whites have their speech reported “as is” complete with all the slang and deviations from Standard English, but no attempts are made to mimic their accents.

(Hmm. I think I just found a research topic for an eager grad student, if anyone wants to grab it.)

And I have definitely run across the early 20th century use of “Hebrew” rather than “Jew”–R. Austin Freeman has his hero John Thorndyke refer to a Jewish lawyer as “a Hebrew”.

Interestingly enough, Freeman reports Irish accents and lower-class Jewish accents, but only reports black speech with an accent when he is writing reporting people speaking in West African patois. Upper-middle class blacks (such as students studying law from Africa) are reported as speaking Standard English and without an accent. Which makes me think that for Freeman, class trumped race.

@grumpy realist:

A while back I used a newspaper archive to determine when this usage faded, which seemed to be around the 1910s or so. “More than 500 Hebrews crowded Clinton Hall last night and took part in an enthusiastic meeting…in honor of Nahum Sokelew, the Zionist, and editor of the best-known Jewish newspaper in Russia.” — The New York Time, 1913.

In the early 2000s there was a legal controversy involving New York kosher statutes, which were so out of date they talked about “Orthodox Hebrew religious requirements.” According to news reports, the rabbis present at a conference on the issue were heard snickering when the archaic language was read aloud.

The usage is preserved in the names of certain Reform organizations such as Hebrew Union College and the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, which only changed its name to the Union for Reform Judaism in 2003.

On rare occasion I have encountered someone who refers to me as a “Hebrew.” I take it to be simple ignorance, but it makes me wonder what other sorts of antiquated attitudes such people may hold about me.

While I was in a vacation in Utah in the early 2000s, I met a middle-aged woman who used the phrase “colored boy”–the only time I’ve ever heard that phrase used outside a movie. I was born in 1977 and grew up in Baltimore. I know “coloured” is still considered a neutral expression in some other countries (in South Africa it refers to people we would describe as mixed-race or multiracial), and of course “person of color” is still regarded as a proper and politically correct usage in the states. But “colored boy”?

Of course, in the 1967 movie Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, the young woman who’s getting married to Sidney Poitier casually refers to him as a “colored man” when talking to her parents. And these are supposedly California liberals.

I’ve mentioned this anecdote before, but Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Gold Bug” contains a depiction of a plantation slave that looks pretty offensive today, but the first time I encountered the story as a kid was a bowdlerized version in which the character is referred to as a “servant,” his patois is translated into Standard English, and the illustrations make his features ambiguous enough that he might be Caucasian. When I got around to reading the original story, its content came as a shock to me. It doesn’t have the excuse of To Kill a Mockingbird or Huckleberry Finn, both highly progressive works for their time that have the temerity to accurately depict the fact that people back then casually used the N-word. In contrast, Poe was simply a racist. But I am really against bowdlerization. In some ways I think it’s worse than outright censorship. Either you show these works to kids, or you don’t. But don’t modify the works to “soften” their impact. To me, that’s essentially rewriting history. (They tried something like that a few years ago with Huck Finn by replacing all mentions of the N-word with the word “slave.”)

@Kylopod: I’m so ignorant that I didn’t realize Jewish people were called Hebrews any time more recently than biblical times. Even then, I could probably use a Venn diagram to understand any overlap between Jews, Hebrews, and Israelites.

@Franklin: Israel is God’s people, not a geographic site or country.

@Franklin:

Why is that ignorant? I know hardly anyone who’s aware of what I mentioned; I didn’t know about it myself until I read about it.

“Hebrews” was the name of the ancient inhabitants of the Land of Israel, later renamed Palestine. “Israelites” is a rough translation of bnei yisrael, literally “children of Israel,” referring to the descendants of Jacob, who changed his name to Israel. In other words, Israelites were the Hebrews after Jacob, and so pre-Jacob figures like Abraham and Isaac were simply Hebrews, but after Jacob the terms become more or less interchangeable.

The Land of Israel was eventually divided into sections, one of them called Judea (now part of the West Bank), settled by descendants of Jacob’s son Judah. After the people of Israel were exiled from the land, for some reason (in a linguistic process that I believe is called pars pro toto) they all began to be called Judeans, or “Jews,” regardless of their specific ancestry. To my knowledge the first recorded example of this usage is the Book of Esther, when Mordecai is referred to as a Jew even though he’s from the tribe of Benjamin, and when Haman plots to destroy the Jews. (There has to be significance to the fact that the first time Jews are called Jews, someone wants to commit genocide against them.)