Veterans on the Supreme Court

RedState‘s Erick Erickson notes that, not only would Elena Kagan replace the Supreme Court’s last Protestant but also “the last of the military veterans on the United States Supreme Court.”

RedState‘s Erick Erickson notes that, not only would Elena Kagan replace the Supreme Court’s last Protestant but also “the last of the military veterans on the United States Supreme Court.”

Indeed, according to his Wikipedia entry, John Paul Stevens “began work on his master’s degree in English at the university in 1941, but soon decided to join the United States Navy, He enlisted on December 6, 1941, one day before Pearl Harbor and served as an intelligence officer in the Pacific Theater from 1942 to 1945. Stevens was awarded a Bronze Star for his service in the codebreaking team whose work led to the downing of Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s plane in 1943.”

But we had a military draft until 1973. How did the six men remaining on the Court manage to avoid service?

It turns out, not all of them did. As Erickson himself notes, Anthony Kennedy served (apparently for only one year, 1961) in the National Guard. But he dismisses this as “definitely not the same. Just ask any leftist who complained about George Bush’s lack of military experience against John Kerry.” Fair enough, really. While the Guard has been an active fighting force going back to Desert Storm, it was rare for units to be called up in the 1960s. Especially since we weren’t at war in 1961.

But a quick search turns up the fact that Samuel Alito, too, served.

While a sophomore at Princeton, Alito received the low lottery number 32, in a Selective Service drawing on December 1, 1969. In 1970, he became a member of the school’s Army ROTC program, attending a six-week basic summer camp that year at Fort Knox, Kentucky, in lieu of having been in ROTC during his first two years in college.

[…]

He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Signal Corps after his graduation and assigned to the United States Army Reserve. Following his graduation from Yale Law School in 1975, he served on active duty from September to December 1975, while attending the Officer Basic Course for Signal Corps officers at Fort Gordon, Georgia. The remainder of his time in the Army was served in the inactive Reserves. He had the rank of Captain when he received an Honorable Discharge in 1980.

Now, again, this is less active duty time than George W. Bush had. But it’s pretty substantial contact with the military, enough at least to give him familiarity with its traditions and culture.

While his Wikipedia article doesn’t mention it, Stephen Breyer served in some capacity with the U.S. Army in 1957. He graduated Stanford in 1959, so presumably it was a short stint, probably as an enlisted man.

None of the other male justices served:

- John Roberts was born in 1955 and thus barely missed the draft era.

- Antonin Scalia was born in 1936 and certainly old enough. He went to military prep school (Francis Xavier) but did not serve in the military. He graduated high school at the tail end of the Korean War, which was followed by a long stretch of relative peace, so perhaps he wasn’t needed.

- Clarence Thomas was born in 1948. Wikipedia says, “Thomas had a series of deferments from the military draft while in college at Holy Cross. Upon graduation, he was classified as 1-A and received a low lottery number, indicating he might be drafted to serve in Vietnam. Thomas reportedly failed his medical exam, due to curvature of the spine, and was not drafted.” It cites a 1991 Newsweek feature.

And, no, neither Ruth Bader Ginsburg nor Sonia Sotomayor served. (Sotomayor’s mother, Celina Báez, did serve in the Women’s Army Corps during WWII.)

In Saturday’s NYT, Phillip Carter, well known in the blogosphere as the longtime proprietor of the now-defunct Intel Dump and more significantly an Iraq War veteran who briefly served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Detainee Policy under President Obama, gets it more accurately and makes the key point:

When Justice John Paul Stevens retires, the Supreme Court will be left without a sitting war veteran. He enlisted in the Navy the day before Pearl Harbor and, as an intelligence officer, was involved with the code-breaking efforts in the Pacific. Decades later, Justice Stevens’s service gave him a visceral appreciation for war and the military institution, and left in him a healthy skepticism toward executive power, particularly the use of that power in wartime. This carried forward into some of his most important opinions, as in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, in 2006, which ruled military commissions inconsistent with the Geneva conventions and America’s system of military justice.

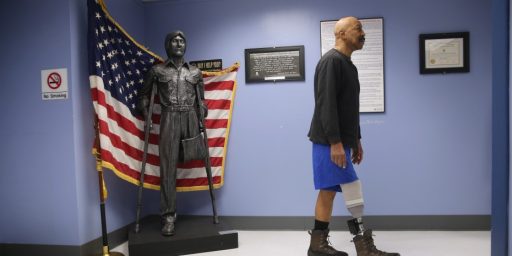

The court’s impending military gap reflects America’s widening civil-military divide: fewer than one percent of Americans serve in the armed forces and, consistent with these numbers, fewer veterans now serve in Congress or on the federal bench than at any time since World War II. But our nation remains at war, and many of the court’s toughest cases arise out of these wars, from battlefield contracts to warrantless surveillance. The Supreme Court needs a new justice who will bring national security credentials, and a personal connection to the military, to its cloistered chambers.

Given that the burden of military duty now falls on a tiny subset of volunteers, I don’t see this trend reversing itself. Perhaps one day Phil will get the nod. He’d not only give us another war veteran on the Court but, as a proud graduate of UCLA’s School of Law, would break the stranglehold of Harvard and Yale graduates.

UPDATE: Commenter Steve gets it exactly right:

Politicians who never served tend to either lionize the military or not trust it. I think that most vets have some degree of healthy skepticism about the military and the use of force, especially those not running for office. The emphasis by the military on the ethics and responsibility surrounding military actions would also be a useful input into the courts.

Now, I don’t support affirmative action for veterans. Aside from ideological objections, there just aren’t enough veterans in the population of under-55 attorneys with the credentials for the Supreme Court. But, if someone with significant military experience made it to the short list, I wouldn’t mind his or her service being used as a tie breaker.

“Decades later, Justice Stevens’s service gave him a visceral appreciation for war and the military institution, and left in him a healthy skepticism toward executive power, particularly the use of that power in wartime.”

So few people serve that it is not likely we will get many more vets, and I would be pleased to see someone like Carter get a shot someday assuming he advances in his career appropriately. He nails it with the quote above. Politicians who never served tend to either lionize the military or not trust it. I think that most vets have some degree of healthy skepticism about the military and the use of force, especially those not running for office. The emphasis by the military on the ethics and responsibility surrounding military actions would also be a useful input into the courts.

Steve

This assumes the selections are made based primarily on merit, rather than ideology and politics.

I’d certainly never make that assumption. SCOTUS nominees almost always went to the right schools, did a SCOTUS judgeship, served as a federal appellate judge or held some other high government office. From that pool, presidents of both parties pick people who are ideological compatible, at least as best they can tell, usually settling on those with a lack of paper trail to ease confirmation.

But, after all that, there’s a short list. It’s not inconceivable a veteran could find himself on it — although it’s unlikely because of the career path needed and requirement to be under 55.

Erickson’s has to be one of the most specious observations about a Supreme Court nomination I’ve ever encountered. More than anything it reflects the absolute desperation in which opponents of the president are reaching for something, anything, to talk about.

First, the notion that one’s veteran status has a substantive influence on one’s policy choices begs the question to a considerable degree.

The Johnson administration was jam-packed with veterans: Dean Rusk, Clark Clifford, and Robert McNamara; Ramsey Clark (that Ramsey Clark) was a veteran; the Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, was a veteran. The Postmaster General was a former Marine, for crying out loud.

So to what extent did the Johnson administration, veteran-heavy as it was, produce “good” policy choices on “military matters” (as Erickson terms them)? Arguably not so much.

Second, how does Erickson square the proposition that Supreme Court justices ought not to be bringing their personal baggage to bear on matters of law — the very definition of “activism” — with the proposition, generally made by the same people who make the first one, that it’s “important” to have a veteran in the event some “military matter” comes before the court.

Third, all veterans are not alike. Should there be a combat litmus test? “Sure Mr. Smith, you’re a brilliant lawyer and you spent 20 years in the military, but at peace, so you’re not really qualified to judge, say, Gitmo.”

Fourth, I find it rather ironic the way “veteran” waxes and wanes as a positive signifier in (generally) conservative discourses like Erickson’s. So John Kerry’s veteran status “didn’t” count; Al Gore’s veteran status “didn’t” count (oh, he was just a journalist!); Jack Murtha’s veteran status “didn’t” count. But George W. Bush’s veteran status “did” count — by golly, he did his duty.

That moving target is rather like the moving target notion of “listening to the generals.” One listens to the generals, I have observed, until they say things you don’t like. So we listened to Shinseki, until Shinseki said things we don’t like. We listened to Petraeus, until Petraeus said things we don’t like.

Sound and fury signifying nothing. Partisanship hiding behind the skirts of military service.

Neither OEF nor OIF has engaged a politically relevant percentage of the electorate, and there’s no reason to expect an OEF/OIF “surge” in policy-relevant positions.

With all due respect to Carter, I think he’s got it exactly wrong. There’s no reason, ex ante, to believe that a veteran would be any more sympathetic to a “pro-military” argument — whatever it is that would look like — flies in the face of logic.

For Erickson to suggest that it’s a tragedy that a veteran is retiring from the Court is simply ludicrous. It’s the pinata school of analysis — I’ll swing until I hit something.

P.S.

USA, USAR 1983-2005; OIF 2003-2004